A Reception Analysis of Chinese Women's Viewing Experiences of Ann Hui's the Golden Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

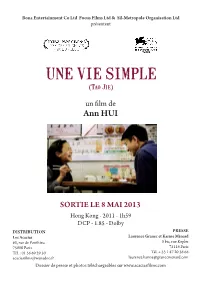

DP Une Vie Simple

Bona Entertainment Co Ltd Focus Films Ltd & Sil-Metropole Organisation Ltd présentent UNE VIE SIMPLE (Tao Jie) un film de Ann HUI SORTIE LE 8 MAI 2013 Hong Kong - 2011 - 1h59 DCP - 1.85 - Dolby DISTRIBUTION PRESSE Les Acacias Laurence Granec et Karine Ménard 63, rue de Ponthieu 5 bis, rue Kepler 75008 Paris 75116 Paris Tél. : 01 56 69 29 30 Tél. + 33 1 47 20 36 66 [email protected] [email protected] Dossier de presse et photos téléchargeables sur www.acaciasfilms.com SYNOPSIS Au service d’une famille bourgeoise depuis quatre générations, la domestique Ah Tao vit seule avec Roger, le dernier héritier. Producteur de cinéma, il dispose de peu de temps pour elle, qui, toujours aux petits soins, continue de le materner... Le jour où elle tombe malade, les rôles s’inversent... ENTRETIEN AVEC ANN HUI Votre film s'inspire de la vie de Roger Lee, un célèbre producteur de cinéma à Hong Kong. Comment avez-vous eu l’idée de faire un film sur lui ? Roger Lee est le producteur du film. On s'est rencontré et il m'a raconté son histoire qui m'a beaucoup plu, et à partir de là, nous avons commencé à rechercher des finan - cements. Je voulais faire un film autour d'une histoire simple concernant les relations de travail entre une domestique et son patron dans le Hong Kong des années 60-70. À quelle occasion avez-vous rencontré Roger Lee pour la première fois ? Roger était co-producteur sur Neige d'été , un film que j'ai réalisé et qui est sorti en 1995. -

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(S): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(s): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring 1994), pp. 65-77 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389334 Accessed: 22-12-2015 11:50 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Discourse. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.157.160.248 on Tue, 22 Dec 2015 11:50:37 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The New Hong Kong Cinema and the Déjà Disparu Ackbar Abbas I For about a decade now, it has become increasinglyapparent that a new Hong Kong cinema has been emerging.It is both a popular cinema and a cinema of auteurs,with directors like Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, Allen Fong, John Woo, Stanley Kwan, and Wong Rar-wei gaining not only local acclaim but a certain measure of interna- tional recognitionas well in the formof awards at international filmfestivals. The emergence of this new cinema can be roughly dated; twodates are significant,though in verydifferent ways. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Beyond New Waves: Gender and Sexuality in Sinophone Women's Cinema from the 1980s to the 2000s Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4h13x81f Author Kang, Kai Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Beyond New Waves: Gender and Sexuality in Sinophone Women‘s Cinema from the 1980s to the 2000s A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Kai Kang March 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Marguerite Waller, Chairperson Dr. Lan Duong Dr. Tamara Ho Copyright by Kai Kang 2015 The Dissertation of Kai Kang is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements My deepest gratitude is to my chair, Dr. Marguerite Waller who gave me freedom to explore my interested areas. Her advice and feedback helped me overcome many difficulties during the writing process. I am grateful to Dr. Lan Duong, who not only offered me much valuable feedback to my dissertation but also shared her job hunting experience with me. I would like to thank Dr Tamara Ho for her useful comments on my work. Finally, I would like to thank Dr. Mustafa Bal, the editor-in-chief of The Human, for having permitted me to use certain passages of my previously published article ―Inside/Outside the Nation-State: Screening Women and History in Song of the Exile and Woman, Demon, Human,‖ in my dissertation. iv ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Beyond New Waves: Gender and Sexuality in Sinophone Women‘s Cinema from the 1980s to the 2000s by Kai Kang Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Comparative Literature University of California, Riverside, March 2015 Dr. -

Gender and the Family in Contemporary Chinese-Language Film Remakes

Gender and the family in contemporary Chinese-language film remakes Sarah Woodland BBusMan., BA (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Languages and Cultures 1 Abstract This thesis argues that cinematic remakes in the Chinese cultural context are a far more complex phenomenon than adaptive translation between disparate cultures. While early work conducted on French cinema and recent work on Chinese-language remakes by scholars including Li, Chan and Wang focused primarily on issues of intercultural difference, this thesis looks not only at remaking across cultures, but also at intracultural remakes. In doing so, it moves beyond questions of cultural politics, taking full advantage of the unique opportunity provided by remakes to compare and contrast two versions of the same narrative, and investigates more broadly at the many reasons why changes between a source film and remake might occur. Using gender as a lens through which these changes can be observed, this thesis conducts a comparative analysis of two pairs of intercultural and two pairs of intracultural films, each chapter highlighting a different dimension of remakes, and illustrating how changes in gender representations can be reflective not just of differences in attitudes towards gender across cultures, but also of broader concerns relating to culture, genre, auteurism, politics and temporality. The thesis endeavours to investigate the complexities of remaking processes in a Chinese-language cinematic context, with a view to exploring the ways in which remakes might reflect different perspectives on Chinese society more broadly, through their ability to compel the viewer to reflect not only on the past, by virtue of the relationship with a source text, but also on the present, through the way in which the remake reshapes this text to address its audience. -

Sesiones ESPECIALES 8 1/2 WOMAN

SEsIONES ESPECIALES 8 1/2 WOMAN 8 1/2 WOMAN Producción: Kees Kasander, para Delux Productions, Continent Films, Movie Master, Woodline Productions. Nacionalidad: Netherlands/United Kingdom/ Luxembourg/Germany 1999. Directed: Peter Greenaway. Guión: Peter Greenaway. Fotografía. Sacha Vierny. Color. Vestuario: Emi Wada. Montaje: Elmer Leupen. Intérpretes: John Standing, Matthew Delamere, Vivian Wo, Annie Shizuka Inoh, Barbara Sarafian, Kirina Mano, Toni Collette, Amanda Plummer, Natacha Amal, Manna Fujiwara, Polly Walker, Elizabeth Berrington , Myriam Muller, Don Warrington, Claire Johnston. Duración: 120 min. V.O.S.E. 8 1/2 Woman es un penetrante e innovador estudio sobre el sexo, el poder, las clases sociales, las culturas, la mujer... Peter Greenaway explora las relaciones entre hombres y mujeres y el sexo en uno de sus films más logrados de los últimos años, en el que retoma su obsesión por las simetrías, los números y las estructuras artificiales, aunque en favor de una trama más accesible y hasta divertida. Un adinerado hombre de unos 55 años pierde a su esposa de toda la vida. Queda desolado por la tristeza. Su hijo intenta consolarlo, le propone reunir a un grupo de mujeres en un castillo y descubrir una sexualidad aún latente. Mujeres con las que ambos experimentarán libremente. 8 y 1/2 mujeres, de distintas procedencias culturales y sociales, son llamadas a integrar el harén. Todas lo hacen a cambio de algo. Con el tiempo, no mucho, padre e hijo se darán cuenta que las mujeres empiezan a desafiar su poder y que son criaturas más complejas que simples pedazos de carne. Una a una se alejan casi hastiadas de la presencia masculina. -

Xiao Hong, La Leyenda Resucitada = Xiao Hong, the Legend Resurrected

XIAO HONG, LA LEYENDA RESUCITADA1 XIAO HONG, THE LEGEND RESURRECTED Shan LU Universidad de Salamanca Resumen: Xiao Hong fue una de “Las Cuatro Talentosas” en la época revolucionaria de China (años treinta del siglo XX), sus novelas volvieron a la vista del público a finales del siglo tras su muerte en los años cuarenta siendo una de las escritoras más estudiadas por el movimiento feminista del país. En este texto, se van a revisar las críticas sobre ella y sus obras con un hilo diacrónico partiendo del contexto social de China. Palabras clave: Xiao Hong, novela, China, críticas, feminismo. Abstract: Xiao Hong was one of "The Four Talented" in China's revolutionary era (1930s), her novels returned to the public in the late twentieth century after her death in the 40's as one of the most studied female writers by the feminist movement of the country. In this text, the criticisms about her and her works will be reviewed with a diachronic thread starting from the social context of China. Key words: Xiao Hong, novel, China, criticism, feminism. 1. INTRODUCCIÓN Xiao Hong (en chino tradicional: 蕭紅, en chino simplificado: 萧红) 2 aparte de ser una de “Las Cuatro Talentosas” en la época revolucionaria de China, recibió el apoyo significativo del fundador de la literatura contemporánea 1 Este artículo se ha realizado en el marco del Proyecto de investigación “Las inéditas” financiado por el Vicerrectorado de Investigación y Transferencia de la Universidad de Salamanca. 2 A partir de ahora, chino simplificado se abrevia con c.s., y chino tradicional se abrevia con c.t. -

Industry Guide Focus Asia & Ttb / April 29Th - May 3Rd Ideazione E Realizzazione Organization

INDUSTRY GUIDE FOCUS ASIA & TTB / APRIL 29TH - MAY 3RD IDEAZIONE E REALIZZAZIONE ORGANIZATION CON / WITH CON IL CONTRIBUTO DI / WITH THE SUPPORT OF IN COLLABORAZIONE CON / IN COLLABORATION WITH CON LA PARTECIPAZIONE DI / WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF CON IL PATROCINIO DI / UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF FOCUS ASIA CON IL SUPPORTO DI/WITH THE SUPPORT OF IN COLLABORAZIONE CON/WITH COLLABORATION WITH INTERNATIONAL PARTNERS PROJECT MARKET PARTNERS TIES THAT BIND CON IL SUPPORTO DI/WITH THE SUPPORT OF CAMPUS CON LA PARTECIPAZIONE DI/WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF MAIN SPONSORS OFFICIAL SPONSORS FESTIVAL PARTNERS TECHNICAL PARTNERS ® MAIN MEDIA PARTNERS MEDIA PARTNERS CON / WITH FOCUS ASIA April 30/May 2, 2019 – Udine After the big success of the last edition, the Far East Film Festival is thrilled to welcome to Udine more than 200 international industry professionals taking part in FOCUS ASIA 2019! This year again, the programme will include a large number of events meant to foster professional and artistic exchanges between Asia and Europe. The All Genres Project Market will present 15 exciting projects in development coming from 10 different countries. The final line up will feature a large variety of genres and a great diversity of profiles of directors and producers, proving one of the main goals of the platform: to explore both the present and future generation of filmmakers from both continents. For the first time the market will include a Chinese focus, exposing 6 titles coming from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Thanks to the partnership with Trieste Science+Fiction Festival and European Film Promotion, Focus Asia 2019 will host the section Get Ready for Cannes offering to 12 international sales agents the chance to introduce their most recent line up to more than 40 buyers from Asia, Europe and North America. -

1 “Ann Hui's Allegorical Cinema” Jessica Siu-Yin Yeung to Cite This

This is the version of the chapter accepted for publication in Cultural Conflict in Hong Kong: Angles on a Coherent Imaginary published by Palgrave Macmillan https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-7766-1_6 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/34754 “Ann Hui’s Allegorical Cinema” Jessica Siu-yin Yeung To cite this article: By Jessica Siu-yin Yeung (2018) “Ann Hui’s Allegorical Cinema”, Cultural Conflict in Hong Kong: Angles on a Coherent Imaginary, ed. Jason S. Polley, Vinton Poon, and Lian-Hee Wee, 87-104, Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. Allegorical cinema as a rhetorical approach in Hong Kong new cinema studies1 becomes more urgent and apt when, in 2004, the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) begins financing mainland Chinese-Hong Kong co-produced films.2 Ackbar Abbas’s discussion on “allegories of 1997” (1997, 24 and 16–62) stimulates studies on Happy Together (1997) (Tambling 2003), the Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002–2003) (Marchetti 2007), Fu Bo (2003), and Isabella (2006) (Lee 2009). While the “allegories of 1997” are well- discussed, post-handover allegories remain underexamined. In this essay, I focus on allegorical strategies in Ann Hui’s post-CEPA oeuvre and interpret them as an auteurish shift from examinations of local Hong Kong issues (2008–2011) to a more allegorical mode of narration. This, however, does not mean Hui’s pre-CEPA films are not allegorical or that Hui is the only Hong Kong filmmaker making allegorical films after CEPA. Critics have interpreted Hui’s films as allegorical critiques of local geopolitics since the beginning of her career, around the time of the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984 (Stokes and Hoover 1999, 181 and 347 note 25), when 1997 came and went (Yau 2007, 133), and when the Umbrella Movement took place in 2014 (Ho 2017). -

A Man of Many Parts Musician, Actor, Director, Producer — Teddy Robin Remembers the Milestones of His Illustrious Showbiz Career Spanning More Than 50 Years

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Friday, July 5, 2019 | 9 Culture profi le A man of many parts Musician, actor, director, producer — Teddy Robin remembers the milestones of his illustrious showbiz career spanning more than 50 years. Mathew Scott listened in. eddy Robin carries with him an it,” says Robin. “I think it was because of want to see them. Some directors make air of enthusiasm that can lift Beatle-mania. I don’t think I handled the fi lms that are too arty. If people don’t see Teddy Robin earned fame as a rock your mood. fame very well. I was shocked.” your fi lms, what’s the use of them?” star but always knew his path would It has you smiling, before you lead him to films. ROY LIU / CHINA DAILY knowT it, almost as broadly as Robin him- A life in the movies Seeking out the best self does when asked fi rst-up if he’s ever Much of the attention, as always in the It’s a point that leads us directly to why thought about the reason behind his run music world, was focused on the lead sing- Robin has come to HKAC. He had a hand of success in the world of Asian entertain- er with the light, bright voice and the fi lm in around 50 fi lms across his career, from ment for more than 50 years. industry in Hong Kong was quick to notice early box-o ce hits such as his debut in “Fate!” is the initial, rapid-fi re response, how the fans fl ocked to Robin. -

An Interview with Ann Hui Visible Secrets: Hong Kong's Women

An Interview with Ann Hui Visible Secrets: Hong Kong’s Women Filmmakers Your 21st century films are quite eclectic. What has driven your choice of projects in recent times? I shot Visible Secrets after two years' teaching and I thought, first, I'd better do a film that was marketable. My first film is also a thriller and I thought it was fun to revisit old grounds. Then followed a film which I was really interested in making (July Rhapsody ), I thought I would never be able to raise funds for it but surprisingly it was accepted by the investor, so I made it. And so forth and so on... alternately, making films I really want to make and some I could just make so as to survive in the industry. Could you talk a little about The Way We Are and Night and Fog? These films seem quite different stylistically; one very much informed by social realism and the other more melodramatic, yet each seems perfect for its subject matter. What made you select these different approaches to the setting of Tin Shui Wai? The Way We Are was initially planned as a D.V. affair since I couldn’t find the money for Night and Fog . It's also initially not about Tin Shui Wai but I decided to transport the whole setting to Tin Shui Wai. The script was already written 7 or 8 years ago about another housing estate but since I knew Tin Shui Wai well, and the lifestyle of all these housing areas are about the same, I thought it would be okay to transpose the whole story to the newest housing estate. -

Journal of Asian Studies Contemporary Chinese Cinema Special Edition

the iafor journal of asian studies Contemporary Chinese Cinema Special Edition Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Editor: Seiko Yasumoto ISSN: 2187-6037 The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue – I IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Editor: Seiko Yasumoto, University of Sydney, Australia Associate Editor: Jason Bainbridge, Swinburne University, Australia Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Rachel Dyer IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2016 ISSN: 2187-6037 Online: joas.iafor.org Cover image: Flickr Creative Commons/Guy Gorek The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue I – Spring 2016 Edited by Seiko Yasumoto Table of Contents Notes on contributors 1 Welcome and Introduction 4 From Recording to Ritual: Weimar Villa and 24 City 10 Dr. Jinhee Choi Contested identities: exploring the cultural, historical and 25 political complexities of the ‘three Chinas’ Dr. Qiao Li & Prof. Ros Jennings Sounds, Swords and Forests: An Exploration into the Representations 41 of Music and Martial Arts in Contemporary Kung Fu Films Brent Keogh Sentimentalism in Under the Hawthorn Tree 53 Jing Meng Changes Manifest: Time, Memory, and a Changing Hong Kong 65 Emma Tipson The Taste of Ice Kacang: Xiaoqingxin Film as the Possible 74 Prospect of Taiwan Popular Cinema Panpan Yang Subtitling Chinese Humour: the English Version of A Woman, a 85 Gun and a Noodle Shop (2009) Yilei Yuan The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Notes on Contributers Dr. -

INFERNAL AFFAIRS (2002, 101 Min.) Online Versions of the Goldenrod Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Links

November 13 2018 (XXXVII:12) Wai-Keung Lau and Alan Mak: INFERNAL AFFAIRS (2002, 101 min.) Online versions of The Goldenrod Handouts have color images & hot links: http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html DIRECTED BY Wai-Keung Lau (as Andrew Lau) and Alan Mak WRITING Alan Mak and Felix Chong PRODUCED BY Wai-Keung Lau producer (as Andrew Lau), line producers: Ellen Chang and Lorraine Ho, and Elos Gallo (consulting producer) MUSIC Kwong Wing Chan (as Chan Kwong Wing) and Ronald Ng (composer) CINEMATOGRAPHY Yiu-Fai Lai (director of photography, as Lai Yiu Fai), Wai-Keung Lau (director of photography, as Andrew Lau) FILM EDITING Curran Pang (as Pang Ching Hei) and Danny Pang Art Direction Sung Pong Choo and Ching-Ching Wong WAI-KEUNG LAU (b. April 4, 1960 in Hong Kong), in a Costume Design Pik Kwan Lee 2018 interview with The Hollywood Reporter, said “I see every film as a challenge. But the main thing is I don't want CAST to repeat myself. Some people like to make films in the Andy Lau...Inspector Lau Kin Ming same mood. But because Hong Kong filmmakers are so Tony Chiu-Wai Leung...Chen Wing Yan (as Tony Leung) lucky in that we can be quite prolific, we can make a Anthony Chau-Sang Wong...SP Wong Chi Shing (as diverse range of films.” Lau began his career in the 1980s Anthony Wong) and 1990s, serving as a cinematographer to filmmakers Eric Tsang...Hon Sam such as Ringo Lam, Wong Jing and Wong Kar-wai. His Kelly Chen...Dr.