Local Government Dissolution in Karachi: Chasm Or Catalyst? Alison Brown, Saeed Ahmed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESMP-KNIP-Saddar

Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Development Department, Government of Sindh Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject Karachi Neighborhood Improvement Project (P161980) Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) October 2017 Environmental and Social Management Plan Final Report Executive Summary Government of Sindh with the support of World Bank is planning to implement “Karachi Neighborhood Improvement Project” (hereinafter referred to as KNIP). This project aims to enhance public spaces in targeted neighborhoods of Karachi, and improve the city’s capacity to provide selected administrative services. Under KNIP, the Priority Phase – I subproject is Educational and Cultural Zone (hereinafter referred to as “Subproject”). The objective of this subproject is to improve mobility and quality of life for local residents and provide quality public spaces to meet citizen’s needs. The Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject ESMP Report is being submitted to Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Development Department, Government of Sindh in fulfillment of the conditions of deliverables as stated in the TORs. Overview the Sub-project Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject forms a triangle bound by three major roads i.e. Strachan Road, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road and M.R. Kayani Road. Total length of subproject roads is estimated as 2.5 km which also forms subproject boundary. ES1: Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject The following interventions are proposed in the subproject area: three major roads will be rehabilitated and repaved and two of them (Strachan and Dr Ziauddin Road) will be made one way with carriageway width of 36ft. -

Impacts of Economic Crises and Reform on the Informal Textile Industry in Karachi

Impacts of economic crises and reform on the informal textile industry in Karachi Arif Hasan with Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban Keywords: April 2015 Informal economy, globalisation, urban development, Karachi About the authors Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, dealing with urban planning and development issues in general and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, including several books published by Oxford University Press and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign community based organizations, national and international NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. e-mail: arifhasan37@gmail. com Mansoor Raza is a freelance researcher and a visiting faculty member at Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology (SZABIST). He is an electrical engineer turned environmentalist, and has been involved with civil Society and NGOs since 1995. He worked as disaster manager in Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Pakistan in Afghanistan Emergency 2002, Tsunami 2004, Kashmir Earthquake -2005 and IDP crisis in 2009. Mansoor also works as a researcher with Arif Hasan and Associates since 1998 on diverse urban issues. He has researched and published widely and has a special interest in the amendment and repeal of discriminatory laws and their misuse in Pakistan. Mansoor blogs at https:// mansooraza.wordpress.com. -

Discovering Myths of Industrial Fire of Baldia-Factory Pakistan

Discovering Myths of Industrial Fire of Baldia-Factory Pakistan Abdul Manan Shaikh,1 Jawaid A. Qureshi,2,* Muhammad Asif Qureshi3 1, 2, Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology (SZABIST), Karachi, Pakistan, 3Universiti Uttara Malaysia *Email: [email protected] Abstract This is a case study of ‘the most terrifying event’ of Baldia Town Factory Karachi-Pakistan, an unfortunate garments facility and exporters that suffered from devastating fire accident on 9/11 of 2012. It caused instant death of 258 factory workers and hundreds injured. The owners belonged to Bhaila Memons – a very successful business community, who had billions of rupees’ investment and exports, employed one thousand workers and paid taxes. The data was garnered from pertinent literature, media content chronicle analysis (MCCA to record almost date-wise records on different developments), and Delphi technique to conduct eight interviews from industry experts. The initial media reports (of renowned newspapers having their news TV and online news channels too) accused the owners for such tragic event. Later on, the government investigation teams revealed shocking facts and held a Karachi-based legal political party responsible for it, as its terrorist wing was allegedly involved in the brutish plot, who perpetrated inferno since the owners of the factory refused to disburse extortion money. Domestic stakeholders, policy makers and international organizations intervened to compensate the victims but sadly, the law courts could not exercise justice. The event was deemed as an assault on the engine of the economy. Keywords: Baldia Town Factory; Industrial Fire; Strategy; Operational Crises; Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) 1. -

HEATSTROKE RELIEF CENTRES in KARACHI JUNE, 2015 Legend

HEATSTROKE RELIEF CENTRES IN KARACHI JUNE, 2015 Legend Rangers Relief Centre and Contact Number .! Ranger Relief Centre Rangers Wing Contact Number Jamshoro Rangers Training Centre and College Toll 2136871683 .! Pakistan Navy Relief Centre Sindh Rangers Hospital, Block A, North 2136670725 Nazimabad Canal HQ 53 Wing, Baldia Town 2132814044 HQ 93 Wing, People’s Football Stadium 2132032629 Street HQ 91 Wing, SITE Stadium 2132597050 Airport/Air Base HQ 72 Wing, Kala Pull 2199202545 HQ 83 Wing, Jamia Milia Malir 2134491746 Mangroves HQ 82 Wing, Muzaffarabad Colony 2135080167 MALIR HQ 63 Wing, Karachi University 2199261056 Landuse HQ 44 Wing, North Karachi 2136493000 Park The Pakistan Rangers, Sindh, in the meantime, has set up 10 “Heatstroke Relief Centres” in the city, where doctors and para-medical staff equipped with modern medical River equipment are available to treat heatstroke patients District Boundary Lasbela Creation Date: June 24, 2015 Projection/Datum: WGS 84 Geographic N N " " 0 0 ' ' Page Size: A3 0 0 ° ° 5 5 HQ 44 wing 2 2 Rangers Training ¯ North Centre & College 0 2.75 5.5 11 Karachi ! KM .! . 0 30 PAF Base Malir 330 (Abandonded) PAF Base MALIR 60 HQ 63 wing Chotta Malir CANTONMENT 300 HQ 53 wing Karachi (Abandonded) Sindh KARACHI Baldia Town Rangers University .! Hospital CENTRAL .! HQ 91 .! wing SITE 270 90 Stadium +92.51.282.0449/835.9288|[email protected] KARACHI .! All Rights Reserved - Copyright 2015 WEST www.alhasan.com Jinnah International DISCLAIMER: Masroor Airport ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Airbase HQ 83 wing This product is the sole property of ALHASAN SYSTEMS Jamia Milia [www.alhasan.com] - A Knowledge Management, Business .! Malir Psychology Modeling, and Publishing Company. -

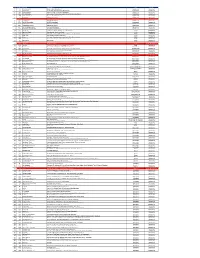

Atms (Operational/Closed)

S. No. ATM ID Location ATM Address City Status 1 24 Abt Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad Abbottabad Operational 2 312 Sarwar Mall Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad Abbottabad Operational 3 345 Abt Jinnahabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad Abbottabad Operational 4 721 Ibb Abbottabad Lodhi Golden Tower Supply Bazar Mansehra Road Abbottabad Abbottabad Operational 5 1024 CMH Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad Abbottabad Operational 6 1721 Abt Kakool 1 Abbottabad Kakool 1 Abbottabad Operational 7 2024 Amc Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad Abbottabad Under Maintenance 8 2721 Abt Kakool 2 Abbottabad Kakool 2 Abbottabad Operational 9 3721 Ibb BRC Abbottabad Ibb BRC Abbottabad Abbottabad Operational 10 4721 Abt Kakool 3 Abbottabad Kakool 3 Abbottabad Operational 11 5721 Abbottabad Kakool 4 Abbottabad Kakool 4 Abbottabad Operational 12 6721 CSD SHOP PMA KAKUL CSD SHOP PMA KAKUL Abbottabad Operational 13 3024 FF CENTRE ABBOTTABAD FF CENTRE ABBOTTABAD Abbottabad Operational 14 131 Kam Kamra Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. Attock Operational 15 149 Pgh Pindi Ghaib Main Katcheri Road Pindi Gheb Attock Operational 16 197 Attock City Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City Attock Operational 17 252 Fateh Jang Main Rawalpindi Road, Fateh Jang Attock Operational 18 333 Khour POL Khour Company,Khour,Tehsil Pindi Gheb, District Attock Attock Operational 19 344 Hassanabdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock Attock Operational 20 1131 Kam Hazroo Kam Hazroo Attock Operational 21 1737 Ibb Hassan Abdal Ibb -

Cost of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) in Motorcycle Crash Victims at a Public Tertiary Healthcare Facility in Karachi, Pakistan: an Analytical Cross-Sectional Study

Study Participant ID# Questionnaire for patients or caregivers: Study Title: Cost of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) in Motorcycle Crash Victims at a Public Tertiary Healthcare Facility in Karachi, Pakistan: An Analytical Cross-sectional Study. Date of Birth of the respondent Date of data collection Respondent Contact Number Data Collector Name with Code# Supervisor’s Name Edited by Entered by Part-a Demographic Variables No. Questions and Filters Coding Categories Skip Answers Q1 What is the Gender of the 1. Male patient? 2. Female Circle one best answer Q2 What is patient’s level of 1. No formal Education education? 2. Less than Primary School Circle one best answer 3. Primary School 4. High School 5. College Diploma 6. Degree 7. Post Graduate and higher. 8. Madrasa education Q3 What is patient’s marital status? 1. Single Circle one best answer 2. Married 3. Widowed 4. Divorced 5. Separated Q4 Is the patient a resident of 1. Yes If No, skip Karachi city? 2. No to Q5 Circle one best answer Q4a Where is the patient living in 1. Baldia Town Karachi? 2. Bin Qasim Town 3. Gadap Town Circle one best answer 4. Gulberg Town 5. Gulshan Town 6. Jamshed Town 7. Kemari Town 8. Korangi Town 9. Landhi Town 10. Liaquatabad Town 11. Lyari Town 12. Malir Town 13. New Karachi Town 14. North Nazimabad Town 15. Orangi Town 16. Saddar Town 17. Shah Faisal Town 18. S.I.T.E. Town Q5 How many members are there in Write exact number of family members in two patient’s family? digits number Q6 What is patient’s role in the 1. -

12086369 01.Pdf

Exchange Rate 1 Pakistan Rupee (Rs.) = 0.871 Japanese Yen (Yen) 1 Yen = 1.148 Rs. 1 US dollar (US$) = 77.82 Yen 1 US$ = 89.34 Rs. Table of Contents Executive Summary Introduction Chapter 1 Review of Policies, Development Plans, and Studies .................................................... 1-1 1.1 Review of Urban Development Policies, Plans, Related Laws and Regulations .............. 1-1 1.1.1 Previous Development Master Plans ................................................................................. 1-1 1.1.2 Karachi Strategic Development Plan 2020 ........................................................................ 1-3 1.1.3 Urban Development Projects ............................................................................................. 1-6 1.1.4 Laws and Regulations on Urban Development ................................................................. 1-7 1.1.5 Laws and Regulations on Environmental Considerations ................................................. 1-8 1.2 Review of Policies and Development Programs in Transport Sector .............................. 1-20 1.2.1 History of Transport Master Plan .................................................................................... 1-20 1.2.2 Karachi Mass Transit Corridors ...................................................................................... 1-22 1.2.3 Policies in Transport Sector ............................................................................................. 1-28 1.2.4 Karachi Mega City Sustainable Development Project (ADB) -

Officer of the Town Health Officer Baldia Town Karachi

• OFFICER OF THE TOWN HEALTH OFFICER BALDIA TOWN KARACHI NO.THO(Baldia)/- Karachi. Dated ker) -2015 To, The Managing Director Sindh Public Procurement Regularity Authority, Government of Sindh, Karachi. or Subject:- BID EVALUATION REPORT. I have the honour to submit herewith the Bid Evaluation Report, Comparative Statement, Minutes of Meeting and Scrutiny Sheet for Purchase of General Medicines and Allied Items and Other Miscellaneous Items for Health Facilities of this 01: town for the year 2014-15 for hoisting on Websitc of SPPRA. l■-• 4 (Z1 arzbjec_V.- TOWN HEALTH OFFICER WRebleANCetttft5 . TOWN HEALTH OFFICER tA, Copy to:- BALDIA TOWN 1. The Secretary to Government of Sindh, Health Department Karachi. 2. The Executive District Officer Health, Karachi. 3. The Accountant General Sindh, Karachi. TOWN HEALTH OFFICER BALDIA TOWN KARACHI MINUTES OF MEETING FOR OPENING OF TENDER FOR THE PURCHASE OF GENERAL MEDICINES & ALLIED ITEMS FOR HEALTH FACILITIES OF BALDIA TOWN, KARACHI FOR THE YEAR 2014-15 A meeting of Procurement Committee of Baldia Town, Karachi was held on 19-01-2015 in the office of the Town Health Officer Baldia Town, Karachi regarding opening of the tender for Purchase of General Medicines & Allied and Other Miscellaneous Items for Health Facilities of Baldia Town, Karachi for the year 2014-15 and attended by following members. Dr. Abdul Haque Bhutto Chairman T.H.O. Baldia Town, Karachi Dr. Mohammad Pervaiz Khan Member Dy. T.H.O. Admin Baldia Town Dr. Nale Mitho - Member Sr. M.O. Sadder Town, Karachi. The following firms participated in the tender. 1. M/S Y.H Enterprises 2. -

Karachi Heatwave Management Plan: a Guide to Planning and Response

Karachi Heatwave Management Plan: A Guide to Planning and Response Commissioner Karachi Purpose of the Document This document, Karachi Heatwave Management Plan, outlines what should happen before, during and after periods of extreme heat in Karachi. It sets out strategies that government and non-government agencies will adopt to prevent heat-related illnesses and deaths in Karachi and capacitate the public, particularly the most vulnerable residents, to take protective action. The Plan describes actions of implementation partners to ensure (1) information on weather conditions and heat health is timely and specific, (2) organizations have the capacity to respond according to their roles, and (3) strategies and actions enabling increase in effectiveness over time. In June 2015 Karachi City experienced a severe heatwave that caused over 1,200 deaths and over 50,000 cases of heat illness. The heatwave caught all levels of government and first responders off-guard, highlighting the need for inter-agency coordination, clarity in roles, and a well-publicized trigger to activate a planned response. To address this need and to prevent health impacts from future heatwaves as climate change intensifies, the Commissioner Office Karachi requested support from the Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) to develop a heatwave management plan. Karachi’s first Heatwave Management Plan is the result of a technical assistance project delivered by national and international experts between October 2016 and May 2017, working closely with the Commissioner Office and other stakeholders. The Plan will be subject to an annual performance review and updated versions will be available to implementation partners accordingly. ii | P a g e Table of Contents List of Figures ...................................................................................................................... -

%Otcti Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 Mitlibries Email: [email protected] Document Services

THE "PRESENT" OF THE PAST: Persistence of Ethnicity in Built Form by KHADIJA JAMAL Bachelor of Architecture NED University of Engineering and Technology Karachi, Pakistan January 1986 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1989 @ Khadija Jamal 1989 All rights reserved The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of author Khadija Jamal Department of Architecture May 12, 1989 Certified by Ronald B. Lewcock Professor of Architecture and Aga Khan Professor of Design for Islamic Societies Thesis Supervisor Accepted by IJ \,j Julian Beinart Chairman, Department Committee for Graduate Students nASSA~IUSETTS INSTiUM OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 0 2 1989 UBMC %otcti Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. The images contained in this document are of the best quality available. THE "PRESENT" OF THE PAST: Persistence of Ethnicity In Built Form by KHADIJA JAMAL Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 12, 1989 in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies ABSTRACT The subject of this thesis was generated by the prevailing social situation in the city of Karachi, where many communities and ethnic groups co-exist in ethnically defined areas. -

West-Karachi

West-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 West Karachi Orangi Town 3-Hanifabad 408040135 GBLSS - NEW STANDARD Middle Boys 42,038 8,408 33,630 8,408 8,408 33,630 134,520 33,630 168,151 2 West Karachi Orangi Town 3-Hanifabad 408040146 GBLSS - FAIRY LAND Middle Mixed 38,468 7,694 23,081 15,387 7,694 30,775 123,099 30,775 153,873 3 West Karachi Orangi Town 5-Madina Colony 408040133 GBLSS - KHURSHID-UL-ISLAM Middle Boys 39,744 7,949 23,846 15,898 7,949 31,795 127,181 31,795 158,976 4 West Karachi Orangi Town 11-Data Nagar 408040139 GGLSS - 5-F KHADDA Middle Mixed 184,500 36,900 110,700 73,800 36,900 147,600 590,400 147,600 738,000 5 West Karachi SITE Town 2-Old Golimar 408020129 GGLSS - TOWN COMMITTEE Middle Girls 40,750 8,150 24,450 16,300 8,150 32,600 130,400 32,600 163,000 6 West Karachi SITE Town 1-Pak Colony 408020107 GGPS - ASIFABAD NO.1 Primary Mixed 16,665 3,333 9,999 6,666 3,333 13,332 53,329 13,332 66,661 7 West Karachi SITE Town 1-Pak Colony 408020111 GGPS - SASIFABAD NO.2 Primary Mixed 18,103 3,621 10,862 7,241 3,621 14,483 57,930 14,483 72,413 8 West Karachi SITE Town 2-Old Golimar 408020109 GGPS - SEVERAGE FARM REXER LINE Primary Mixed 17,383 3,477 10,430 6,953 3,477 13,906 55,624 13,906 69,530 9 West Karachi SITE Town 3-Jahanabad 408020037 GGPS - SHERSHAH Primary -

Creative Solutions R-3, Row-8, Block-C, National Cement Society, Block-10A, Gulshan-E-Iqbal, Karachi-Pakistan

Creative Solutions R-3, Row-8, Block-C, National Cement Society, Block-10A, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi-Pakistan. Mob: 0321-8222043 / Fax: 021-34984579 / Email: [email protected] Address : R-3, Row-8, Block-C, National Cement Society, Block-10A, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi-Pakistan. Mobile : 0321-8222043 Fax : 021-34984579 E-mail : [email protected] URL : www.creativesolutions.net.pk M/s Creative Solutions firm was established in the year 2007 with the object of providing Engineering & Consultancy Services in Electrical installation fields. Over the period of last five years the firm has achieved its goal of providing technical sound and safe Electrical installation services all over Karachi. We have a well equipped team of professional engineers, supervisors and workmen to plan & execute different jobs according to the requirements of our clients to achieve excellent engineering standards. We have undertaken almost all type of electrical jobs such as completion / execution of H.T, L.T Bulk supply sub-station, scheme works of all size of pole mounted Transformers, H.T, L.T panels, H.T, L.T cable laying & fixing work, Cellular Towers Electric connections, Dedicated PMT Schemes and maintenance of cellular towers power supply in Karachi. EXECUTED WORKS OF M/S TELENOR BTS POWER CONNECTIONS WITH DEDICATED PMT, L.T SPANS AND CABLE SCHEME CASES SCHEME CASES OF M/S TELENOR BTS TOWER POWER CONNECTIONS S.No Projects(Address) Description/ Job Executed 15 KVA Transformer with 2 H.T Spans of copper 01. Plot NO.R-211 P.R.E.C.H.S. Gulistan-e-Johar Karachi conductor 3 SWG and 2 H.