The Great Andamanese Tribe and Its Perception of Time by Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded Dataset, and the Bi-Labelled Individual Completely Removed

An exploratory analysis of combined genome-wide SNP data from several recent studies Blaise Li Abstract The usefulness of a ‘total-evidence’ approach to human population genetics was assessed through a clustering analysis of combined genome-wide SNP datasets. The combination contained only 3146 SNPs. Detailed examination of the results nonetheless enables the extraction of relevant clues about the history of human populations, some pertaining to events as ancient as the first migration out of Africa. The results are mostly coherent with what is known from history, linguistics, and previous genetic analyses. These promising results suggest that cross-studies data confrontation have the potential to yield interesting new hypotheses about human population history. Key words: Data combination, Graphical representation, Human populations, Single nucleotide polymorphism 1. Introduction Let this introduction begin with a disclaimer: I am not a population geneti- cist, but a phylogeneticist who happens to be interested in human popula- tion history. The results presented here should not be considered as scientific claims about human population histories, but only as hypotheses that might deserve further investigation. arXiv:1101.5519v4 [q-bio.PE] 6 Dec 2012 In human population genetics, numerous papers have recently been pub- lished using genome-wide SNP (Single Nucleotide Polymorphism) data for populations of various places in the world. These papers often represent the data by means of PCA (Principal Component Analysis) plots or clustering bar plots. The details of such graphical representations suggest a variety of interesting hypotheses concerning the relationships between populations. However, it is frustrating to see the data scattered between different studies. -

In Search of Language Contact Between Jarawa and Aka-Bea: the Languages of South Andaman1

Acta Orientalia 2011: 72, 1–40. Copyright © 2011 Printed in India – all rights reserved ACTA ORIENTALIA ISSN 0001-6483 In search of language contact between Jarawa and Aka-Bea: The languages of South Andaman1 Anvita Abbi and Pramod Kumar Cairns Institute, Cairns, Australia & Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Abstract The paper brings forth a preliminary report on the comparative data available on the extinct language Aka-Bea (Man 1923) and the endangered language Jarawa spoken in the south and the central parts of the Andaman Islands. Speakers of Aka-Bea, a South Andaman language of the Great Andamanese family and the speakers of Jarawa, the language of a distinct language family (Abbi 2006, 2009, Blevins 2008) lived adjacent to each other, i.e. in the southern region of the Great Andaman Islands in the past. Both had been hunter-gatherers and never had any contact with each other (Portman 1899, 1990). The Jarawas have been known for living in isolation for thousands of years, coming in contact with the outside world only recently in 1998. It is, then surprising to discover traces of some language-contact in the past between the two communities. Not a large database, but a few examples of lexical similarities between Aka-Bea and Jarawa are 1 The initial version of this paper was presented in The First Conference on ASJP and Language Prehistory (ALP-I), on 18 September 2010, Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany. We thank Alexandra Aikhnevald for helpful comments on an earlier version of the paper. 2 Anvita Abbi & Pramod Kumar investigated here. -

Unconventional Linguistic Clues to the Negrito Past Robert Blust University of Hawai‘I, Honolulu, Hawai‘I, [email protected]

Human Biology Volume 85 Issue 1 Special Issue on Revisiting the "Negrito" Article 18 Hypothesis 2013 Terror from the Sky: Unconventional Linguistic Clues to the Negrito Past Robert Blust University of Hawai‘i, Honolulu, Hawai‘i, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol Part of the Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, and the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Blust, Robert (2013) "Terror from the Sky: Unconventional Linguistic Clues to the Negrito Past," Human Biology: Vol. 85: Iss. 1, Article 18. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol/vol85/iss1/18 Terror from the Sky: Unconventional Linguistic Clues to the Negrito Past Abstract Within recorded history. most Southeast Asian peoples have been of "southern Mongoloid" physical type, whether they speak Austroasiatic, Tibeto-Burman, Austronesian, Tai-Kadai, or Hmong-Mien languages. However, population distributions suggest that this is a post-Pleistocene phenomenon and that for tens of millennia before the last glaciation ended Greater Mainland Southeast Asia, which included the currently insular world that rests on the Sunda Shelf, was peopled by short, dark-skinned, frizzy-haired foragers whose descendants in the Philippines came to be labeled by the sixteenth-century Spanish colonizers as "negritos," a term that has since been extended to similar groups throughout the region. There are three areas in which these populations survived into the present so as to become part of written history: the Philippines, the Malay Peninsula, and the Andaman Islands. All Philippine negritos speak Austronesian languages, and all Malayan negritos speak languages in the nuclear Mon-Khmer branch of Austroasiatic, but the linguistic situation in the Andamans is a world apart. -

Unique Origin of Andaman Islanders: Insight from Autosomal Loci

J Hum Genet (2006) 51:800–804 DOI 10.1007/s10038-006-0026-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Unique origin of Andaman Islanders: insight from autosomal loci K. Thangaraj Æ G. Chaubey Æ A. G. Reddy Æ V. K. Singh Æ L. Singh Received: 9 April 2006 / Accepted: 1 June 2006 / Published online: 19 August 2006 Ó The Japan Society of Human Genetics and Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract Our mtDNA and Y chromosome studies Introduction lead to the conclusion that the Andamanese ‘‘Negrito’’ mtDNA lineages have survived in the Andaman Is- The ‘‘Negrito’’ populations found scattered in parts of lands in complete genetic isolation from other South southern India, the Andaman Islands, Malaysia and the and Southeast Asian populations since the initial set- Philippines are considered to be the relic of early tlement of the region by the out-of-Africa migration. In modern humans and hence assume considerable order to obtain a robust reconstruction of the evolu- anthropological and genetic importance. Their gene tionary history of the Andamanese, we carried out a pool is slowly disappearing either due to assimilation study on the three aboriginal populations, namely, the with adjoining populations, as in the case of the Se- Great Andamanese, Onge and Nicobarese, using mang of Malaysia and Aeta of the Philippines, or due autosomal microsatellite markers. The range of alleles to their population collapse, as is evident in the case of (7–31.2) observed in the studied population and het- the aboriginals of the Andaman Islands. The Andaman erozygosity values (0.392–0.857) indicate that the se- and Nicobar Islands are inhabited by six enigmatic lected STR markers are highly polymorphic in all the indigenous tribal populations, of which four have been three populations, and genetic variability within the characterized traditionally as ‘‘Negritos’’ (the Jarawa, populations is significantly high, with a mean gene Onge, Sentinelese and Great Andamanese) and two as diversity of 77%. -

The Jarawa of the Andamans

Te Jarawa of the Andamans Rhea John and Harsh Mander* India’s Andaman Islands are home to some of the some scholars describe appropriately as ‘adverse most ancient, and until recently the most isolated, inclusion’.1 Te experience of other Andaman tribes peoples in the world. Today barely a few hundred like the Great Andamanese and the Onge highlight of these peoples survive. Tis report is about one of poignantly and sombrely the many harmful these ancient communities of the Andaman Islands, consequences of such inclusion.2 Te continued the Jarawa, or as they describe themselves, the Ang. dogged resistance of the Sentinelese to any contact with outsiders makes them perhaps the most Until the 1970s, and even to a degree until the isolated people in the world. On the other hand, 1990s, the Jarawa people fercely and ofen violently the early adverse consequences of exposure of the defended their forest homelands, fghting of a Jarawa people to diseases and sexual exploitation diverse range of incursions and ofers of ‘friendly’ by outsiders, suggest that safeguarding many forms contact—by other tribes-people, colonial rulers, of ‘exclusion’ may paradoxically constitute the best convicts brought in from mainland India by the chance for the just and humane ‘inclusion’ of these colonisers, the Japanese occupiers, independent highly vulnerable communities. India’s administration, and mainland communities settled on the islands by the Indian government. Since However, the optimal balance between isolation the 1990s, two of the three main Ang communities and contact with the outside world of such have altered their relationship with the outsider of indigenous communities is something that no many hues, accepting their ‘friendship’ and all that government in the modern world has yet succeeded came with it, including health care support, clothes, in establishing. -

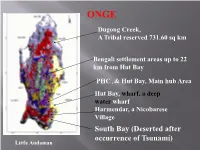

South Bay (Deserted After Occurrence of Tsunami)

ONGE Dugong Creek, A Tribal reserved 731.60 sq km Bengali settlement areas up to 22 km from Hut Bay PHC , & Hut Bay, Main hub Area Hut Bay, wharf, a deep water wharf Harmendar, a Nicobarese Village South Bay (Deserted after occurrence of Tsunami) Little Andaman Little Andaman (LA) Island once was exclusively the abode of the OG until early 1960s OG tribe, settled at Dugong Creek (DC) & South Bay, LA in 1978 Post-Tsunami situation relocated them a little away from DC The geographical isolation of Dugong and South Bay offers a secure resemblance of nomadic pursuits, and the tropical rain forest, ecology, creeks, rivulets, sea etc are conducive to sustain foraging activities throughout the year. Age-wise population Age Male Female Total Sex group) (in years) N % N % N % Ratio 0-10 25 53.19 22 46.81 47 100 880 11-20 11 57.89 08 42.11 19 100 727 21-30 07 53.85 06 46.15 13 100 857 31-40 03 30 07 70 10 100 2333 41-50 03 42.85 04 57.15 07 100 1333 51+ 04 36.36 07 63.64 11 100 1750 53 49.53 54 50.47 107 100 1019 *AAJVS *Till June 2012 Socio-Economic condition of the Onge As semi-nomad forager, hunting & fishing were their fortes, fond of dugong that they hunt on full moon night Being animists, belief on ancestral assistance in various foraging activities Observed adolescent ritual for a month long usually followed by smearing their bodies & hunting as well Body painting with red ochre & white clay common Dead is buried under the large bedstead in the hut, which is then deserted Monogamy stringently adhered to as marriage rules, re-marriage of widow or widower allowable Pre-tsunami situation, Dugong Creek Onge settlement deserted Post-tsunami situation, Dugong Creek Intrinsic designs, which are usually painted by womenfolk on their loving spouses & on themselves too. -

Stature, Mortality, and Life History Among Indigenous Populations of the Andaman Islands, 1871–1986

713 attainment of stature before agriculture and urbanization cre- Reports ated conditions favoring the reduction of body size (Stini 1975). This argument suggests that larger body size would be characteristic of hunter-gatherers and human populations in Stature, Mortality, and Life History among general due to past selective pressure. Indigenous Populations of the Andaman Several studies have documented negative secular trends in stature (Bogin, Keep, and Edwards 1996; Price 1985; Tobias Islands, 1871–1986 1975, 1985; Torretta et al. 1994). These temporal decreases in J. T. Stock and A. B. Migliano stature demonstrate that a reduction in body size may be found during periods of particular hardship. Few studies have Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies, documented long-term changes in body size among hunter- Department of Biological Anthropology, University of gatherers or other nonagricultural societies. When this has Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3DZ, United been done, researchers have identified neutral or positive sec- Kingdom ([email protected]). 3 V 09 ular trends (Comuzzie et al. 1995; Pretty et al. 1998; Tobias 1975). While there is significant evidence for small stature among undernourished populations, poor nutrition may not Despite considerable interest in the evolution of small body be the only factor influencing small body size. Differences in size, there is little evidence for changes in body size within growth and age-related stature are likely to have some genetic small-bodied human populations. This study combines an- basis (Martorell 1985). thropometric data from a number of studies of the body size Small-bodied people (pygmies) are often considered to be of Andaman Islanders from 1871 to 1986. -

1 Linguistic Clues to Andamanese Pre-History

Linguistic clues to Andamanese pre-history: Understanding the North-South divide Juliette Blevins Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology ABSTRACT The Andaman Islands, were, until the 19th century, home to numerous hunter-gatherer societies. The ten or so tribes of Great Andamanese spread over the north and central parts of the islands are thought to have spoken related languages, while the Onge, Jangil and Jarawa of the southern parts, including Little Andaman, have been assumed to constitute a distinct linguistic family of 'Ongan' languages. Preliminary reconstruction of Proto-Ongan shows a potential link to Austronesian languages (Blevins 2007). Here, preliminary reconstructions of Proto-Great Andamanese are presented. Two interesting differences characterize the proto-languages of northern vs. southern tribes. First, sea-related terms are easily reconstructable for Proto-Great Andamanese, while the same is not true of Proto-Ongan. Second, where Proto-Ongan shows an Austronesian adstrate, Proto-Great Andamanese includes lexemes which resemble Austroasiatic reconstructions. These linguistic clues suggest distinct prehistoric origins for the two groups. 1. An introduction to languages and peoples of the Andaman Islands. The Andaman Islands are a cluster of over 200 islands in the Bay of Bengal between India and Myanmar (Burma) (see Map 1). [MAP 1 AROUND HERE; COURTESY OF GEORGE WEBER] They were once home to a range of hunter-gatherer societies, who are best known from the descriptions of Man (1883) and Radcliffe-Brown (1922). These writers, along with the Andamanese themselves, split the population of the Andamans into two primary language/culture groups, the 'Great Andaman Group' and the 'Little Andaman Group' (Radcliffe-Brown 1922:11). -

Colonial Practices in the Andaman Islands

For Cileme of course! And for Appa on his seventy fifth. 1 2 DEVELOPMENT AND ETHNOCIDE: COLONIAL PRACTICES IN THE ANDAMAN ISLANDS by Sita Venkateswar Massey University - Palmerston North Aotearoa/New Zealand IWGIA Document No. 111 - Copenhagen 2004 3 DEVELOPMENT AND ETHNOCIDE: COLONIAL PRACTICES IN THE ANDAMAN ISLANDS Author: Sita Venkateswar Copyright: IWGIA 2004 – All Rights Reserved Editing: Christian Erni and Sille Stidsen Cover design, typesetting and maps: Jorge Monrás Proofreading: Elaine Bolton Prepress and Print: Eks/Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark ISBN: 87-91563-04-6 ISSN: 0105-4503 Distribution in North America: Transaction Publishers 390 Campus Drive / Somerset, New Jersey 08873 www.transactionpub.com INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS Classensgade 11 E, DK 2100 - Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: (45) 35 27 05 00 - Fax: (45) 35 27 05 07 E-mail: [email protected] - Web: www.iwgia.org 4 This book has been produced with financial support from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs 5 CONTENTS Map ..............................................................................................................9 Preface ..........................................................................................................10 Prologue: a Sense of Place .......................................................................12 The island ecology ......................................................................................14 The passage to the field site ......................................................................18 -

The Dependence of Andaman and Nicobar Island Tribal Communities on Herbal Remedies

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 9, Issue 11 Ver. II (Nov. 2015), PP 45-53 www.iosrjournals.org The Dependence of Andaman and Nicobar Island Tribal Communities on Herbal Remedies Dr. Jyoti Dwivedi Department of Environmental Biology A.P.S. University Rewa (M.P.) 486001India Abstract: The tribal people of the Andaman and Nicobar islands are neither 'primitive' nor living in the 'stone age'. Their way of life has not remained unchanged for thousands of years. Like all peoples, their cultures have been continuously evolving. There is no reason why the tribes cannot both survive and thrive, as long as their lands and resources are secure. The tribal people live in interior village deep inside dense forests and are dependent on many medicinal plants growing nearby.Living close to nature, the tribal people have acquired knowledge on the natural resources that exists around their habitat in the forest eco-system.These people have unique knowledge on use of different plant parts, their use in cure of ailment, and are using different formulations made out of plant parts in cure of ailments in primary health care. It is a part of their cultural practices and provides the means for maintaining health and preventing diseases among them. In India, about 1.5 million practitioners of herbal medicine use around 25,000 plant based formulations, of which only 10 percent are used in drug and pharmaceutical industries. The present paper explores, the Plant species used by the tribals of Andaman and Nicobar Island as Herbal Remedies. -

Descriptive and Typological Study of Jarawa Doctor Of

DESCRIPTIVE AND TYPOLOGICAL STUDY OF JARAWA Thesis submitted to the Jawaharlal Nehru University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Pramod Kumar under the supervision of Prof. Anvita Abbi & Prof. Bernard Comrie CENTRE FOR LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE, LITERATURE, AND CULTURE STUDIES JAWAHARLAL NEHRU UNIVERSITY NEW DELHI – 110067 2012. Centre for Linguistics School of Language, Literature & Culture Studies lawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi-ll0067, India Dated: 2-0 . 0\ · '2.-011- CERTIFICATE This thesis titled "Descriptive & Typological Study of Jarawa" submitted by Mr. Pramod Kumar, Centre for Linguistics, School of Language, Literature, and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, is an original work and has not been submitted so far in part or in full, for any other degree or diploma of any University or Institution. ntis may be placed before the examiners for evaluation for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy . ~~ (PROF. ANVITA 1\B]31) (PROF. BERNARD COMRIE) SUPERVISOR JOINT-SUPERVISOR .! ew I, ~ , • > . I .. ' '" !_¢."7 PROF. FRANSON D. MANJALI CHAIRPERSON Tel: +91-11-26704199 Fax: +91- I 1-26741586 DECLARATION BY THE CANDIDATE This thesis titled "Descriptive & Typological Study of Jarawa" submitted by me for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, is an original work and has not been submitted so far in part or in full, for any other degree or diploma of any University or Institute. PRAMOD KUMAR Ph. D. student Centre for Linguistics SLL&CS/JNU i Acknowledgements In the completion of this thesis, I am indebted to a lot of people whom, I must acknowledge. -

Is Great Andamanese Genealogically and Typologically Distinct from Onge and Jarawa? Q

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Language Sciences 31 (2009) 791–812 www.elsevier.com/locate/langsci Is Great Andamanese genealogically and typologically distinct from Onge and Jarawa? q Anvita Abbi * Jawaharlal Nehru University, Centre for Linguistics, New Delhi, Delhi 110 067, India Received 4 October 2007; received in revised form 22 February 2008; accepted 23 February 2008 Abstract India represents five language families: Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Austroasiatic, Tibeto-Burman and Andamanese. The origin of Andamanese tribes and its relationship with Southeast population have been the subject of speculation for cen- turies. Latest research by geneticists [Thangaraj, K. et al. Reconstructing the origin of Andaman Islanders. Science 308, 996] of complete mitochondrial DNA sequences from two out of three accessible tribes, i.e. Onges and Great Andamanese populations, revealed two deeply branching clades that share their most recent common ancestor in founder haplogroup M, with lineages spread among India, Africa, East Asia, New Guinea, and Australia. Linguistic evidence indicating such a bifurcation among the Andamanese languages had been proposed earlier as well [cf. Radcliffe-Brown, 1914; Radcliffe-Brown, A.R., 1922, 1929, 1948 (3rd print). The Andaman Islanders. Free Press, Glen- coe, Illinois]. Much later, Abbi [Abbi, A., 2003. Vanishing voices of the languages of the Andaman Islands. Paper pre- sented at the Max Planck Institute, Leipzig, June 13], on the basis of a pilot survey of the Andamanese languages, indicated that there are possibilities of establishing Great Andamanese language(s) forming a distinct family from the one that Jarawa and Onge belong to. Subsequently, an extensive fieldwork on the Great Andamanese language by the author and the fresh data from Jarawa further reconfirms her judgment explicated in the present paper.