Choosing the Right Fabric Concepts and Tips for Costumers—And Those Who Work with Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

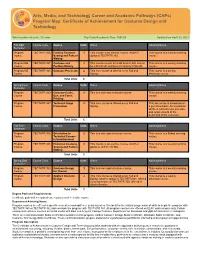

Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology

Arts, Media, and Technology Career and Academic Pathways (CAPs) Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology Total number of units: 23 units Top Code/Academic Plan: 1006.00 Updated on April 25, 2021 Fall Odd Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 366 Fantasy Costume 3 This course is an elective course. Another This course is a weekly morning Course Sewing and Pattern option is TECTHTR 365. course. Making Program/GE TECTHTR 367 Costume and 3 This course counts as a GE Area C Arts course This course is a weekly morning Course Fashion History for LACCD GE and Area C1 Arts for CSU GE. course. Program/GE TECTHTR 345 Costume Practicum 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This course is a weekly Course Spring. afternoon course. Total Units 8 Spring Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 363 Costume Crafts, 3 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a weekly morning Course Dye, and Fabric course. Printing Program TECTHTR 342 Technical Stage 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This lab course is scheduled on Course Production Spring. a per show basis. An orientation will be held to discuss schedule and requirements at the beginning of the semester. Total Units 5 Fall Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 305 Orientation to 2 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a Friday morning Course Technical Careers course. in Entertainment Program TECTHTR 365 Historical Costume 3 This course is an elective course. -

Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout

English by Alain Stout For the Textile Industry Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Compiled and created by: Alain Stout in 2015 Official E-Book: 10-3-3016 Website: www.TakodaBrand.com Social Media: @TakodaBrand Location: Rotterdam, Holland Sources: www.wikipedia.com www.sensiseeds.nl Translated by: Microsoft Translator via http://www.bing.com/translator Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Table of Contents For Word .............................................................................................................................. 5 Textile in General ................................................................................................................. 7 Manufacture ....................................................................................................................... 8 History ................................................................................................................................ 9 Raw materials .................................................................................................................... 9 Techniques ......................................................................................................................... 9 Applications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Textile trade in Netherlands and Belgium .................................................................... 11 Textile industry ................................................................................................................... -

A Producer's Handbook

DEVELOPMENT AND OTHER CHALLENGES A PRODUCER’S HANDBOOK by Kathy Avrich-Johnson Edited by Daphne Park Rehdner Summer 2002 Introduction and Disclaimer This handbook addresses business issues and considerations related to certain aspects of the production process, namely development and the acquisition of rights, producer relationships and low budget production. There is no neat title that encompasses these topics but what ties them together is that they are all areas that present particular challenges to emerging producers. In the course of researching this book, the issues that came up repeatedly are those that arise at the earlier stages of the production process or at the earlier stages of the producer’s career. If not properly addressed these will be certain to bite you in the end. There is more discussion of various considerations than in Canadian Production Finance: A Producer’s Handbook due to the nature of the topics. I have sought not to replicate any of the material covered in that book. What I have sought to provide is practical guidance through some tricky territory. There are often as many different agreements and approaches to many of the topics discussed as there are producers and no two productions are the same. The content of this handbook is designed for informational purposes only. It is by no means a comprehensive statement of available options, information, resources or alternatives related to Canadian development and production. The content does not purport to provide legal or accounting advice and must not be construed as doing so. The information contained in this handbook is not intended to substitute for informed, specific professional advice. -

Effects on Printing Quality According to Yarn Twist and Knitting Structure of Media in Digital Textile Printing(I)

한국염색가공학회지 제22권 제3호 2010년 Textile Coloration and Finishing Vol. 22, No. 3, 2010 〈연구논문〉 DTP(Digital Textile Printing)에서 미디어의 원사꼬임 및 편성구조가 프린팅 Quality에 미치는 영향(I) 박순영†․전동원․박윤철1․이범수2 이화여자대학교 의류직물학과, 1한국생산기술연구원 융복합기술연구본부, 2한국생산기술연구원 경기기술지원본부 Effects on Printing Quality according to Yarn Twist and Knitting Structure of Media in Digital Textile Printing(I) Soon Young Park†, Dong Won Jeon, Yoon Cheol Park1 and Beom Soo Lee2 Dept. of Clothing and Textile, Ewha Womans University, Seoul 120-750, Korea 1Textile Fusion Technology R&D Dept., Institute of Industrial Technology(KITECH), Ansan 426-171, Korea 2e-Color Technology Service Center Dept., Institute of Industrial Technology(KITECH), Ansan 426-171, Korea (Received: March 28, 2010/Revised: July 16, 2010/Accepted: July 29, 2010) Abstract― Digital textile printing(DTP) is becoming more important because the production trend of textile printing goods is adapting to small-lot multiple items. Recently enhanced use of DTP is closely connected with production of high value-added products in fashion industry, which is also appropriate for quick response system(QRS). Quality of DTP depends on pre-treatment, after-treatment, ink, media, printer, etc. One of these parameters, Selection of good media is very important to obtain high quality of DTP products. Especially, the effects of media on printing quality of DTP according to yarn twist and structure of knitting fabric were examined in this study. Two types of yarn twist of 830 t.p.m and 1630 t.p.m for cotton knit were used and five types of media structures were knitted with single circular knitting machine. -

Guide to the Preparation of an Area of Distribution Manual. INSTITUTION Clemson Univ., S.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ID 087 919 CB 001 018 AUTHOR Hayes, Philip TITLE Guide to the Preparation of an Area of Distribution Manual. INSTITUTION Clemson Univ., S.C. Vocational Education Media Center.; South Carolina State Dept. of Education, Columbia. Office of Vocational Education. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 100p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$4.20 DESCRIPTORS Business Education; Clothing Design; *Distributive Education; *Guides; High School Curriculum; Manuals; Student Developed Materials; *Student Projects IDENTIFIERS *Career Awareness; South Carolina ABSTRACT This semester-length guide for high school distributive education students is geared to start the student thinking about the vocation he would like to enter by exploring one area of interest in marketing and distribution and then presenting the results in a research paper known as an area of distribution manual. The first 25 pages of this document pertain to procedures to follow in writing a manual, rules for entering manuals in national Distributive Education Clubs of America competition, and some summary sheet examples of State winners that were entered at the 25th National DECA Leadership Conference. The remaining 75 pages are an example of an area of distribution manual on "How Fashion Changes Relate to Fashion Designing As a Career," which was a State winner and also a national finalist. In the example manual, the importance of fashion in the economy, the large role fashion plays in the clothing industry, the fast change as well as the repeating of fashion, qualifications for leadership and entry into the fashion world, and techniques of fabric and color selection are all included to create a comprehensive picture of past, present, and future fashion trends. -

Textile Preview Salesforce

NEWSPAPER 2ND CLASS $2.99 VOLUME 75, NUMBER 39 SEPTEMBER 20–26, 2019 THE VOICE OF THE INDUSTRY FOR 74 YEARS RETAIL Nontraditional Retail Is Setting Trends in Retail Real Estate By Andrew Asch Retail Editor Representatives of some of the newest trends in retail took the stage at the I nternational Council of Shopping Centers’ W estern Conference Deal Making convention, which ran Sept. 16–1 at the Los Angeles Con ention Center in the city’s downtown. Speaking on the conference’s experiential-retail panel were Allison Samek, chief executive officer of F red Segal, and Tony Sekora, director of real-estate development at Nordstrom nc Samek said that the brand would build new stores overseas, a plan that was announced earlier this year when the retailer was acquired in March for an undisclosed amount by the brand-licensing agency G lobal cons. Retail Real Estate page 18 SUSTAINABILITY DuPont Sorona Makes a Sustainable-Apparel Connection With Farm- to-Table Food Sourcing the dark side By Dorothy Crouch Managing Editor Through establishing parallels between the locally sourced, slow-food movement and the slowing down of For her Spring 2020 collection, designer Dalia MacPhee made florals a bit apparel production from fast fashion, DuPont Sorona hosted an event on Sept. 11 to promote more-responsible approaches more magical by relying on season-appropriate prints in deeper hues. to fashion. Bringing together professionals from the apparel business, garment-industry watchdogs and environmental- MICHAEL BEZJIAN conservation organizations, Sorona illustrated how principles from farm-to-table food sourcing could be applied to fashion manufacturing. -

All Hands Are Enjoined to Spin : Textile Production in Seventeenth-Century Massachusetts." (1996)

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1996 All hands are enjoined to spin : textile production in seventeenth- century Massachusetts. Susan M. Ouellette University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Ouellette, Susan M., "All hands are enjoined to spin : textile production in seventeenth-century Massachusetts." (1996). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1224. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1224 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UMASS/AMHERST c c: 315DLDb0133T[] i !3 ALL HANDS ARE ENJOINED TO SPIN: TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MASSACHUSETTS A Dissertation Presented by SUSAN M. OUELLETTE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 1996 History ALL HANDS ARE ENJOINED TO SPIN: TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MASSACHUSETTS A Dissertation Presented by SUSAN M. OUELLETTE Approved as to style and content by: So Barry/ J . Levy^/ Chair c konJL WI_ Xa LaaAj Gerald McFarland, Member Neal Salisbury, Member Patricia Warner, Member Bruce Laurie, Department Head History (^Copyright by Susan Poland Ouellette 1996 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ALL HANDS ARE ENJOINED TO SPIN: TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MASSACHUSETTS FEBRUARY 1996 SUSAN M. OUELLETTE, B.A., STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PLATTSBURGH M.A., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Ph.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Directed by: Professor Barry J. -

![Sloppy Sweaters [And] Tweed Skirts:” Proposed Styles for the Wartime College Woman Jennifer M](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7587/sloppy-sweaters-and-tweed-skirts-proposed-styles-for-the-wartime-college-woman-jennifer-m-317587.webp)

Sloppy Sweaters [And] Tweed Skirts:” Proposed Styles for the Wartime College Woman Jennifer M

International Textile and Apparel Association 2013: Regeneration, Building a Forward Vision (ITAA) Annual Conference Proceedings Jan 1st, 12:00 AM We wore “sloppy sweaters [and] tweed skirts:” Proposed styles for the wartime college woman Jennifer M. Mower Oregon State University Elaine L. Pedersen Oregon State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/itaa_proceedings Part of the Fashion Design Commons Mower, Jennifer M. and Pedersen, Elaine L., "We wore “sloppy sweaters [and] tweed skirts:” Proposed styles for the wartime college woman" (2013). International Textile and Apparel Association (ITAA) Annual Conference Proceedings. 119. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/itaa_proceedings/2013/presentations/119 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Symposia at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Textile and Apparel Association (ITAA) Annual Conference Proceedings by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New Orleans, Louisiana 2013 Proceedings We wore “sloppy sweaters [and] tweed skirts:”1 Proposed styles for the wartime college woman Jennifer M. Mower and Elaine L. Pedersen, Oregon State University Keywords: World War II, Historic analysis, Clothing needs By Fall 1943 about half of all U. S. college students were women as men left the campuses to fight in World War II. Because of this shift many U.S. colleges tailored their courses and programs to female students.2 National periodicals also focused attention on the co- eds. The purpose of this study was to examine proposed styles for college women during WWII to help historians analyze and put into context dress worn by college women during the war. -

Historic Costuming Presented by Jill Harrison

Historic Southern Indiana Interpretation Workshop, March 2-4, 1998 Historic Costuming Presented By Jill Harrison IMPRESSIONS Each of us makes an impression before ever saying a word. We size up visitors all the time, anticipating behavior from their age, clothing, and demeanor. What do they think of interpreters, disguised as we are in the threads of another time? While stressing the importance of historically accurate costuming (outfits) and accoutrements for first- person interpreters, there are many reasons compromises are made - perhaps a tight budget or lack of skilled construction personnel. Items such as shoes and eyeglasses are usually a sticking point when assembling a truly accurate outfit. It has been suggested that when visitors spot inaccurate details, interpreter credibility is downgraded and visitors launch into a frame of mind to find other inaccuracies. This may be true of visitors who are historical reenactors, buffs, or other interpreters. Most visitors, though, lack the heightened awareness to recognize the difference between authentic period detailing and the less-than-perfect substitutions. But everyone will notice a wristwatch, sunglasses, or tennis shoes. We have a responsibility to the public not to misrepresent the past; otherwise we are not preserving history but instead creating our own fiction and calling it the truth. Realistically, the appearance of the interpreter, our information base, our techniques, and our environment all affect the first-person experience. Historically accurate costuming perfection is laudable and reinforces academic credence. The minute details can be a springboard to important educational concepts; but the outfit is not the linchpin on which successful interpretation hangs. -

CTDA Guide to Filming Live Theater

GUIDE TO FILMING LIVE THEATER ARCHIVAL FILMING GUIDELINES AND LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE CTDA PROJECT PUBLISHED BY DIGITAL SCHOLARSHIP AND PROGRAMS UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI LIBRARIES VERSION 0.1 JANUARY 2012 GUIDE TO FILMING LIVE THEATER ARCHIVAL FILMING GUIDELINES AND LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE CTDA PROJECT VERSION 0.1 JANUARY 2012 WRITTEN BY: NOELIS MÁRQUEZ XAVIER MERCADO LILLIAN MANZOR MARK BUCHHOLZ BRYANNA HERZOG EDITED BY: BRYANNA HERZOG PUBLISHED BY DIGITAL SCHOLARSHIP AND PROGRAMS UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI LIBRARIES FUNDED IN PART BY: ANDREW W. MELLON FOUNDATION UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI LIBRARIES COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES WWW.CUBANTHEATER.ORG COPYRIGHT © 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Equipment List 3 Filming Guidelines 4 Stage Design 5 Camera Placement 5 Filming With Two Cameras 6 Filming Considerations 8 Leadroom and Headroom 8 Avoiding the Audience 8 Light – Brightness Changes and Adjustments 9 Behind the Camera 10 Videographer –vs– Director of Photography 10 When do you use Close-ups, Mid Shots and/or Wide Angles? 10 When do you use zooms? 15 Showcasing production and costume design 16 How do you start and end the show? 16 When do you stop recording? 16 What do you do during Intermissions? 16 Audio Guidelines 17 Editing Guidelines 18 Justifying the Cut 18 Catch the Emotion 19 Best Angle for the Action 19 Emphasizing Rhythm 20 Dividing a Series of Actions 20 Covering Personalities 21 Scene Changes 21 Concealing Errors 22 Editing pre-performance, intermission, and post-performance 22 The Dissolve Transition 22 Things NOT TO DO 22 Color Correction -

GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] +1(347)636.6681 AWARDS + HONORS SKILLS ASHLEY LAW EDUCATION WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL

ASHLEY LAW GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] http://ashleylaw.info +1(347)636.6681 linkedin.com/in/ashley-law instagram.com/_ashleylaw EDUCATION AWA RDS SKILLS SCHOOL OF VISUAL + GRAPHIS (GOLD) SOFTWARE ARTS (New York) NEW TALENT ANNUAL InDesign HONORS BFA Design Editorial Design “Zine”- Illustrator 2017–2019 2018 Photoshop PremierePro AfterEffects SCHOOL OF THE SVA HONOR’S LIST Sketch ART INSTITUTE OF 2017–2018 CHICAGO (Chicago) Fine Art + Visual CAPABILITIES & Critical Studies SAIC MERIT Branding 2013–2015 SCHOLARSHIP Content Production 2013–2015 Identity System Interactive/Digital Design Print + Editorial Design Typography WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL Junior Graphic Design for the GCL team focusing on CREATIVE LAB Designer creative direction of special projects, 06. 2019 - Present (New York) under the direction of Shu Hung and John Jay. Campaigns include collaborations (i.e. Lemaire, JW Anderson, Alexander Wang) and new store openings. MATTE PROJECTS Design Intern Designing client proposals, print, 01. 2019–04. 2019 (New York) digital & social collateral for marketing agency. Worked on projects for Cartier, The Chainsmokers, Moda Operandi & MATTE events (FNT, BLACK-NYC, Full Moon Festival, La Luna). PYT OPERANDI Creative Project Associate for artist management & creative 03–06. 2016 Associate project development company with emphasis (Hong Kong) in film, photography, exhibitions, project & business development consulting. CLOVER GROUP Intimates Design Designed for leading global manufacturer INTL LIMITED. Intern of intimate apparel, emphasis on the 08–10. 2015 (Hong Kong) Victoria’s Secret account. Visually detailed creative direction, identity & design of project pitches. Similar work for clients including Wacoal, Aerie, Lane Bryant. GIORGIO ARMANI Menswear R&D Shadowed Manager of R&D department OPERATIONS Intern for Menswear at HK Armani Corporate 06–09. -

Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association

For internal use only Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association. All rights reserved. Student(s): School: Selection: Troupe: 4 | Superior 3 | Excellent 2 | Good 1 | Fair SKILLS Above standard At standard Near standard Aspiring to standard SCORE Job Understanding Articulates a broad Articulates an Articulates a partial Articulates little and Interview understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the Articulation of the costume costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role designer’s role and specific and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; job responsibilities; thoroughly presents adequately presents and inconsistently presents does not explain an presentation and and explains the explains the executed and explains the executed executed design, creative explanation of the executed executed design, creative design, creative decisions, design, creative decisions decisions or collaborative design, creative decisions, decisions, and and collaborative process. and/or collaborative process. and collaborative process. collaborative process. process. Comment: Design, Research, A well-conceived set of Costume designs, Incomplete costume The costume designs, and Analysis costume designs, research, and script designs, research, and research, and analysis Design, research and detailed research, and analysis address the script analysis of the script do not analysis addresses the thorough script artistic and practical somewhat address the address the artistic and artistic and practical needs analysis clearly address needs of the production artistic and practical practical needs of the (given circumstances) of the artistic and practical and support the unifying needs of the production production or support the the script to support the needs of production and concept.