Kirchner, Carolin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE and BEYOND February 25 - March 18, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release February 1994 JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE AND BEYOND February 25 - March 18, 1994 A film retrospective of the legendary French actress Jeanne Moreau, spanning her remarkable forty-five year career, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on February 25, 1994. JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE AND BEYOND traces the actress's steady rise from the French cinema of the 1950s and international renown as muse and icon of the New Wave movement to the present. On view through March 18, the exhibition shows Moreau to be one of the few performing artists who both epitomize and transcend their eras by the originality of their work. The retrospective comprises thirty films, including three that Moreau directed. Two films in the series are United States premieres: The Old Woman Mho Wades in the Sea (1991, Laurent Heynemann), and her most recent film, A Foreign Field (1993, Charles Sturridge), in which Moreau stars with Lauren Bacall and Alec Guinness. Other highlights include The Queen Margot (1953, Jean Dreville), which has not been shown in the United States since its original release; the uncut version of Eva (1962, Joseph Losey); the rarely seen Mata Hari, Agent H 21 (1964, Jean-Louis Richard), and Joanna Francesa (1973, Carlos Diegues). Alternately playful, seductive, or somber, Moreau brought something truly modern to the screen -- a compelling but ultimately elusive persona. After perfecting her craft as a principal member of the Comedie Frangaise and the Theatre National Populaire, she appeared in such films as Louis Malle's Elevator to the Gallows (1957) and The Lovers (1958), the latter of which she created a scandal with her portrayal of an adultress. -

Al Pacino Receives Bfi Fellowship

AL PACINO RECEIVES BFI FELLOWSHIP LONDON – 22:30, Wednesday 24 September 2014: Leading lights from the worlds of film, theatre and television gathered at the Corinthia Hotel London this evening to see legendary actor and director, Al Pacino receive a BFI Fellowship – the highest accolade the UK’s lead organisation for film can award. One of the world’s most popular and iconic stars of stage and screen, Pacino receives a BFI Fellowship in recognition of his outstanding achievement in film. The presentation was made this evening during an exclusive dinner hosted by BFI Chair, Greg Dyke and BFI CEO, Amanda Nevill, sponsored by Corinthia Hotel London and supported by Moët & Chandon, the official champagne partner of the Al Pacino BFI Fellowship Award Dinner. Speaking during the presentation, Al Pacino said: “This is such a great honour... the BFI is a wonderful thing, how it keeps films alive… it’s an honour to be here and receive this. I’m overwhelmed – people I’ve adored have received this award. I appreciate this so much, thank you.” BFI Chair, Greg Dyke said: “A true icon, Al Pacino is one of the greatest actors the world has ever seen, and a visionary director of stage and screen. His extraordinary body of work has made him one of the most recognisable and best-loved stars of the big screen, whose films enthral and delight audiences across the globe. We are thrilled to honour such a legend of cinema, and we thank the Corinthia Hotel London and Moët & Chandon for supporting this very special occasion.” Alongside BFI Chair Greg Dyke and BFI CEO Amanda Nevill, the Corinthia’s magnificent Ballroom was packed with talent from the worlds of film, theatre and television for Al Pacino’s BFI Fellowship presentation. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Understanding Screenwriting'

Course Materials for 'Understanding Screenwriting' FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 Evan Wm. Cameron Professor Emeritus Senior Scholar in Screenwriting Graduate Programmes, Film & Video and Philosophy York University [Overview, Outline, Readings and Guidelines (for students) with the Schedule of Lectures and Screenings (for private use of EWC) for an extraordinary double-weighted full- year course for advanced students of screenwriting, meeting for six hours weekly with each term of work constituting a full six-credit course, that the author was permitted to teach with the Graduate Programme of the Department of Film and Video, York University during the academic years 2001-2002 and 2002-2003 – the most enlightening experience with respect to designing movies that he was ever permitted to share with students.] Overview for Graduate Students [Preliminary Announcement of Course] Understanding Screenwriting FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 FA/FILM 4501 A 6.0 & FA/FILM 4501 B 6.0 Understanding Screenwriting: the Studio and Post-Studio Eras Fall/Winter, 2002-2003 Tuesdays & Thursdays, Room 108 9:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. Evan William Cameron We shall retrace within these courses the historical 'devolution' of screenwriting, as Robert Towne described it, providing advanced students of writing with the uncommon opportunity to deepen their understanding of the prior achievement of other writers, and to ponder without illusion the nature of the extraordinary task that lies before them should they decide to devote a part of their life to pursuing it. During the fall term we shall examine how a dozen or so writers wrote within the studio system before it collapsed in the late 1950s, including a sustained look at the work of Preston Sturges. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

The Rice Thresher Volume 59, Number 14 Thursday

4> s New coach Conover speaks out on academics, athletics by GARY RACHLIN things that I'd like to get done and how getting a "1" for the program . breakfast entirely. As far as lunch, I'm Last Saturday, President Hackerman will they affect Rice University. So I'm Thresher: Do you have any desire for going to leave it up to the football announced that Rice's new head coach going to be very cautious about what I an athletic dorm at Rice? team. During the season and spring- is A1 Conover and the new athletic di- do. Conover: An athletic dormitory? At practice we will have training table for rector is "Red" Bale. Monday I had an Thresher: What sort of things do you Rice? Not at Rice University. I wouldn't lunch, but for the rest oft the time, the interview with Conover. Excerpts follow: need for a successful football program even consider that. That's absurd. decision will be left to the team. at Rice? Thresher: Would you suggest any Thresher: The evening meal will be at Thresher: Coach Peterson had some di- Conover: One of the things that I have changes in the training table? the colleges for those periods other than fficulties concerning the relationship in, mind concerns people who are coming Conover: First thing I'm going to do the season or spring training. between academic and athletics at Rice. into Rice University, not only football away with is breakfast—all year long. Conover: Yes—just like it's been. How do you see football fitting into Thresher: How will you sell Rice Uni- the scheme of things at Rice Univer- versity to recruits? sity? Conover: Well there are a number of Conover: When I came to Rice Uni- things we are concentrating on when we versity last year with Coach Peterson I talk to recruits. -

Ruidoso, Nm 88345

... .f . .. .. ·Wal-Mart Man walks·to L opening Tuesday :raise funds i. .. 'Seep~ge6A Seepage 3A NO. 86 IN OUR 40TH YEAR 35e PER COpy . MONDA~MA~CH3,1986 . RUIDOSO, NM 88345 . Council, commission Patch",,"ork . , . adopt~mbulance progress policy· The Grindstone dam pro ject now (left) and one year ago (below) shows be to by FRANKIE JARRELL &mders presented four points of routed the scene. the significant amount of News Staff Writer a "basic" agreement he and Diane Sanders said point four states that in .cases where a call goes progress that has been Fisher, atto.rney for Southwest made in the canyon. An Lincoln County and Village of Community Health Services directly to any ambulance service uthat service shall respond to the . access road leading to Ruidoso offic~ Fri.day agreed to (parent organizationforRHVH)" the dam site was just be· adopt policy guidelines to coor had drafted. ., call if it has an' ambulance That agreement states in item available." .' ing started last year, and dinate all emergency medical care now is finished and providers in Lincoln County. one thatambuIance servicesinthis Discussions centered on how the A joint meeting called for 2 p.m. county are normally dispatched by dispatcher can determine the handling traffic. The ac at RuidoSo Village Han got off to a the Sheriffs Office or the Ruidoso closest ambulance service, and the tual dam location (left, late start after commissioners, Police. sugges.tion was made that upper left) now is a busy Ruidoso's. mayorandlegaladvisers Item two continues: u a dispat HresponSe time" should replace site of activity-last year for both governments and the cher ••• shall in all instances direct wording that suggests physical only thick forest stood Ruidoso-Hondo Valley Hospital the call to the. -

MONTHLY GUIDE April 2015 | ISSUE 69 | South Africa / Zimbabwe / Zambia

MONTHLY GUIDE APRIL 2015 | ISSUE 69 | SOUTH AFRICA / ZIMBABWE / ZAMBIA Sophia: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow Vanilla and Chocolate School Is Over Fedez And more EUROCHANNEL GUIDE | MAY 2015 | 1 HOLLYWOOD BROOKLYN MAY 29 - JUNE 7 2015 ILLUMINATE EDITION Venues: WYTHE HOTEL // WINDMILL STUDIOS NYC NITEHAWK CINEMA // MADE IN NY MEDIA CENTER BY IFP 2 | EUROCHANNEL GUIDE | MAY 2015 | MONTHLY GUIDE| MAY 2015 | ISSUE 70 Sophia: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow following our five successful editions, this month, we present the lineup of our much beloved month on Eurochannel, a unique occasion in the year to appreciate Italy beyond stereotypes and mainstream cinema from Hollywood, and to be delighted with the greatest cinematic productions from “The Boot of Europe.” Welcome to the 6th Edition of the Italian Month: Viva il Cinema! Vanilla and Chocolate These enchanting movies gather a number of A-list actors offering us the performances of a lifetime. This month, you can enjoy the talent of Italian top-billed stars such as comedy legend Diego Abatantuono, Maria Grazia Cucinotta (The World Is Not Enough, Il Postino: The Postman, The Rite, The Sopranos, The Simpsons). But beyond awards and festivals, the films and documentaries present in this edition offer a common thing: the desire to overcome difficulties and to offer hope and encouragement to pursue our dreams. In films such as School Is Over, we witness how a conflicted teenager is rescued by his Fedez teachers, who also save their marriage in the process. Legends also teach us the importance of perseverance despite the tribulations that may arise. Documentaries such as Sophia: Yesterday, Table of Today, and Tomorrow, and Tonino Guerra, A Poet in the Movies reveal the contents dreams, hurdles, passions and setbacks of Italian cinema legends Sophia Loren and Tonino Guerra. -

XIX:12) Arthur Penn NIGHT MOVES (1975, 100 Min)

November 17, 2009 (XIX:12) Arthur Penn NIGHT MOVES (1975, 100 min) Directed by Arthur Penn Written by Alan Sharp Produced by Robert M. Sherman Original Music by Michael Small Cinematography by Bruce Surtees Film Editing by Dede Allen Gene Hackman...Harry Moseby Jennifer Warren...Paula Susan Clark...Ellen Moseby Ed Binns...Joey Ziegler Harris Yulin...Marty Heller Kenneth Mars...Nick Janet Ward...Arlene Iverson James Woods...Quentin Melanie Griffith...Delly Grastner Anthony Costello...Marv Ellman John Crawford...Tom Iverson Ben Archibek...Charles Max Gail...Stud Stunts: Dean Engelhardt, Ted Grossman, Richard Hackman, Chuck Hicks, Terry Leonard, Rick Lockwood, Ernie F. Orsatti, Enemy Lines (2001), The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), Heist Chuck Parkison Jr., Betty Raymond, Ronnie Rondell Jr., Walter (2001/I), Heartbreakers (2001), The Mexican (2001), Under Scott, Fred M. Waugh, Glenn R. Wilder, Suspicion (2000), Enemy of the State (1998), Twilight (1998), Absolute Power (1997), The Chamber (1996), The Birdcage ARTHUR PENN (27 September 1922, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, (1996), Get Shorty (1995), Crimson Tide (1995), The Quick and USA—) directed 27 film and dozens of tv episodes, among them the Dead (1995), Wyatt Earp (1994), Geronimo: An American Inside (1996), Penn & Teller Get Killed (1989), Dead of Winter Legend (1993), The Firm (1993), Unforgiven (1992), Company (1987), Target (1985), Four Friends (1981), The Missouri Breaks Business (1991), Class Action (1991), Postcards from the Edge (1976), Night Moves (1975), Little Big Man (1970), Alice's -

2016 Film Writings by Roderick Heath @ Ferdy on Films

2016 Film Writings by Roderick Heath @ Ferdy On Films © Text by Roderick Heath. All rights reserved. Contents: Page Man in the Wilderness (1971) / The Revenant (2015) 2 Titanic (1997) 12 Blowup (1966) 24 The Big Trail (1930) 36 The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) 49 Dead Presidents (1995) 60 Knight of Cups (2015) 68 Yellow Submarine (1968) 77 Point Blank (1967) 88 Think Fast, Mr. Moto / Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937) 98 Push (2009) 112 Hercules in the Centre of the Earth (Ercole al Centro della Terra, 1961) 122 Airport (1970) / Airport 1975 (1974) / Airport ’77 (1977) / The Concorde… Airport ’79 (1979) 130 High-Rise (2015) 143 Jurassic Park (1993) 153 The Time Machine (1960) 163 Zardoz (1974) 174 The War of the Worlds (1953) 184 A Trip to the Moon (Voyage dans la lune, 1902) 201 2046 (2004) 216 Bride of Frankenstein (1935) 226 Alien (1979) 241 Solaris (Solyaris, 1972) 252 Metropolis (1926) 263 Fährmann Maria (1936) / Strangler of the Swamp (1946) 281 Viy (1967) 296 Night of the Living Dead (1968) 306 Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016) 320 Neruda / Jackie (2016) 328 Rogue One (2016) 339 Man in the Wilderness (1971) / The Revenant (2015) Directors: Richard C. Sarafian / Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu By Roderick Heath The story of Hugh Glass contains the essence of American frontier mythology—the cruelty of nature met with the indomitable grit and resolve of the frontiersman. It‘s the sort of story breathlessly reported in pulp novellas and pseudohistories, and more recently, of course, movies. Glass, born in Pennsylvania in 1780, found his place in legend as a member of a fur-trading expedition led by General William Henry Ashley, setting out in 1822 with a force of about a hundred men, including other figures that would become vital in pioneering annals, like Jim Bridger, Jedediah Smith, and John Fitzgerald. -

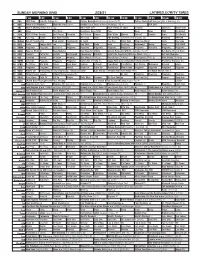

Sunday Morning Grid 2/28/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/28/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News College Basketball Villanova at Butler. (N) Å College Basketball Michigan State at Maryland. (N) 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Boston Bruins at New York Rangers. (N) Å PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Luminess MAXX Oven 7 ABC News This Week Eyewitness News 9AM News News News NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Harvest Cancer? Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Paid Prog. Emeril Fox News Sunday The Issue News PBA Bowling Tournament of Champions. (N) RaceDay NASCAR 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Paid Prog. Silver Coin Drug-Free Relief News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Smile Copper Chef Titan AAA New YOU! Smile Ideal Paid Prog. Bathroom? Money Ideal THE VIRUS 2 2 KWHY Programa Programa Revitaliza Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Revitaliza Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Food as Medicine Yoga-Diabetes Easy Yoga for Arthritis Ancient Remedies With Dr. Josh Axe (TVG) Å Ken Burns: Here & There 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Joyful Pain Free Living With Lee Albert (TVG) Å Eat Your Medicine 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Amazing Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å Blue Bloods (TV14) Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Como dice el dicho (N) Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

Cartolina Serata in Piazza Maggiore

lunedì 25 giugno Piazza Maggiore, ore 22.00 Omaggio a John Boorman dal 23 al 30 Point Blank giugno (Senza un attimo di tregua, USA/1967) 2012 Regia: John Boorman. Sceneggiatura: Alexander Jacobs, David satira di costume, al quadretto pittoresco, un registro romanzesco Newhouse, Rafe Newhouse. Fotografia: Philip H. Lathrop. Scenografia: dove il groviglio dei rapporti umani si rifletteva nella complessità XXVI edizione Keogh Gleason. Musica: Johnny Mandel. Interpreti e personaggi: Lee dell’intrigo. Point Blank, al contrario, si sottrae alla caratterizzazione Marvin (Walker), Angie Dickinson (Chris), Keenan Wynn (Yost), e alla psicologia, riduce le motivazioni all’essenziale, ignora le storie Carroll O’Connor (Brewster), Lloyd Bochner (Frederick Carter), tortuose e sfocia con naturalezza nella fiaba. L’adozione del flashback Michael Strong (Stegman). Produzione: Judd Bernard e Robert da parte di Boorman, lungi dall’essere gratuita a causa dell’influenza Chartoff per Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Durata: 92’ europea, come gli hanno rimproverato alcuni, non fa che riallacciarsi Copia proveniente da BFI National Archive per concessione di alle tendenze generali del racconto. I ritorni al passato sono molto Hollywood Classics diversi da quelli che si incontrano nei polizieschi classici. Il loro valore Versione originale con sottotitoli italiani esplicativo è sottile: le informazioni che ci svelano avrebbero potuto essere fornite con due o tre frasi di dialogo. Nessuna psicologia ma Alla presenza di John Boorman una forza poetica e fisica. Point Blank all’apparenza sembra una storia di vendetta. E lo è fino in Precede fondo. Ma non è sbagliato vedervi anche un apologo più complesso, 1912. Novantasei film di cento anni fa un quadro simbolico dell’America.