Facilitating Distinctive and Meaningful Change Within U.S. Law Schools (Part 2): Pursuing Successful Plan Implementation Through Better Resource Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front Matter

Volume 123 Issue 3 SYMPOSIUM: Discretion and Misconduct: Examining the Roles, Functions, and Duties of the Modern Prosecutor Spring 2019 Front Matter Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlr Part of the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation Front Matter, 123 Dick. L. Rev. (2019). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlr/vol123/iss3/1 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\D\DIK\123-3\toc1233.txt unknown Seq: 1 3-MAY-19 12:48 Table of Contents SYMPOSIUM Introduction ...................................Michael J. Slobom 587 Prosecutorial Discretion: The Difficulty and Necessity of Public Inquiry ...............Bruce A. Green 589 The Impact of Prosecutorial Misconduct, Overreach, and Misuse of Discretion on Gender Violence Victims ................Leigh Goodmark 627 Between Brady Discretion and Brady Misconduct ......................Bennett L. Gershman 661 Prosecutorial Misconduct: Mass Gang Indictments and Inflammatory Statements .................................. K. Babe Howell 691 The Policing of Prosecutors: More Lessons from Administrative Law? ..................Aaron L. Nielson 713 Remarks on Prosecutorial Discretion and Immigration ................... Shoba Sivaprasad Wadhia 733 COMMENTS The Fire Rises: Refining the Pennsylvania Fireworks Law so that Fewer People Get Burned ........................ Sean Philip Kraus 747 \\jciprod01\productn\D\DIK\123-3\toc1233.txt unknown Seq: 2 3-MAY-19 12:48 Standing for Standing Rock?: Vindicating Native American Religious and Land Rights by Adapting New Zealand’s Te Awa Tupua Act to American Soil . -

03-04 Dean's Report

Dean’s Report 2003 - 2004 CONTENTS 2 Carter Named Alumna of the Year DEAN BOARD OF DIRECTORS 3 Anthony A. Tarr 2002-2005 Craig Borowski ‘00 Program on Law and State ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR ACADEMIC AFFAIRS James Gilday ‘86 Government Symposium Andrew R. Klein Amy E. Hamilton ‘89 ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR GRADUATE STUDIES Scott D. Yonover ‘89 4 Jeffrey W. Grove Fall Semester Lectures 2003-2006 ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR STUDENT SERVICES Page Gifford ‘75 AND ADMISSIONS Gilbert L. Holmes ‘99 5 Angela M. Espada Linda L. Meier ‘87 Inaugural Leibman Forum Hon. Margret G. Robb ‘78 ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR TECHNOLOGY Patrick J. Schauer ‘79 Thomas Allington 8 Donald L. Simkin ‘74 Kennedy Scholars Program ASSISTANT DEAN FOR EXTERNAL AFFAIRS Hon. G. Michael Witte ‘82 Jonna M. Kane MacDougall, ’86 2004-2007 9 DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT Hon. Cynthia Ayers ‘82 Scholarship and Award Recipients Carol Neary Richard N. Bell ‘75 James Hernandez ‘85 DIRECTOR OF PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Victor Ippoliti ‘99 16 AND PRO BONO PROGRAMS Tandra Johnson ‘98 Annual Report of Private Giving Shannon L. Williams John Maley ‘88 Tammy J. Meyer ‘89 DIRECTOR OF ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE 17 Hon. Gary L. Miller ‘80 Jo-Ann B. Feltman Partners in Progress Mariana Richmond ‘91 Hon. Robert H. Staton ‘55 19 SCHOOL OF LAW ALUMNI ASSOCIATION Jerome Withered ‘80 John Holt 2004-2005 Sally F. Zweig ‘86 PRESIDENT 20 Robert W. Wright ’90 Dean’s Council VICE PRESIDENT Mary F. Panzi ’88 21 Law School Associates SECRETARY Nathan Feltman ’94 26 TREASURER Law Firm and Corporate Campaign Eric Riegner ’88 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL -

Matthew Jackson

Matt Jackson, Ph.D. College of Communications The Pennsylvania State University 105 Carnegie Building University Park, PA 16802-5101 Office: (814) 863-6419 [email protected] Cell phone: 814-404-1171 ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE July 2004 – Present: Associate Professor of Communications and Department Head, Department of Telecommunications, College of Communications, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA. Courses taught: Survey of Electronic Media and Telecommunications, Media Programming Strategies, Telecommunications Regulation, Internet Law, Communications Law, Telecommunications Policy (graduate course), Copyright Law (graduate course), Broadcast/Cable Management, First Year Seminar, Graduate Colloquium. August 1998 – June 2004: Assistant Professor of Communications, College of Communications, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA. Deans’ Excellence Award for Integrated Scholarship, 2003. Courses taught: See above. August 1996 – May 1998: Associate Instructor, Department of Telecommunications, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. Teaching Excellence Recognition Award, 1996, 1997. Courses taught: Fundamentals of Production, Telecommunications Industries and Management. June 1995: Instructor, Summer Journalism Institute-University of Florida, Gainesville, FL. Course taught: Broadcast Journalism. August 1994 - May 1995: Graduate Assistant, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL. Course taught: Fundamentals of Radio and Television Production. VISITING APPOINTMENTS April 2006: Research Fellow, Centre for Media and Communications -

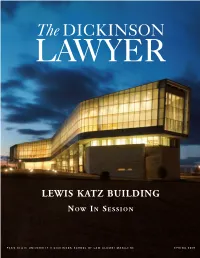

Thedickinson Kelly R

30323_C1_C3_C4:30323_C1_C3_C4 4/15/2009 3:17 AM Page 1 The DICKINSON LAWYER LEWIS KATZ BUILDING N OW I N S ESSION PENN STATE UNIVERSITY’S DICKINSON SCHOOL OF LAW ALUMNI MAGAZINE SPRING 2009 30323_C2_43Rev2:75777_cover1_21.qxd 4/20/2009 7:05 PM Page c2 A LETTER FROM THE DEAN The good fortune of The Dickinson School of Law continues as we com- memorate the onset of the Law School’s 175th Anniversary with the April 24, 2009, dedication of our magnificent new Lewis Katz Building in University Park. We’ll conclude this historic anniversary next spring with the dedication of our new and renovated facility in Carlisle. In December, the ABA took the unprecedented step of granting the Law School’s new University Park campus immediate full approval and recognizing The Dickinson School of Law, in Carlisle and University Park, as the nation’s only unified two-location law school. We continue to serve as the ABA’s national pilot project for reassessing the “distance education” rules applicable to all U.S. law schools, and students in both of our locations continue to enjoy the rich curriculum enabled by our advanced audiovisual telecommunications capabilities. This year, over 4,100 extremely talented, diverse students applied for admis- sion to our law school — the highest number in the history of the Law School; by way of comparison, 1,471 students applied for admission in 2003. The aca- demic credentials and diversity of our students are stronger than at any time in the last thirty years. Outstanding scholars and advocates of renown continue to join our faculty. -

An Early and Ongoing Commitment to Experiential Education: Introduction

Penn State Dickinson Law Dickinson Law IDEAS Faculty Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship Fall 2017 Section III: An Early and Ongoing Commitment to Experiential Education: Introduction Laurel Terry [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/fac-works Recommended Citation Laurel Terry, Section III: An Early and Ongoing Commitment to Experiential Education: Introduction, 122 Dickinson L. Rev. 99 (2017). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction to Section III: An Early and Ongoing Commitment to Experiential Educationi Section III of the Tradition, Innovation & New Beginnings is- sue of the Dickinson Law Review is entitled An Early and Ongoing Commitment to Experiential Education. The three items in this sec- tion, which span more than 100 years, demonstrate Dickinson Law's long-standing interest in, and commitment to, experiential education. The first item that is republished in this section is an editorial that appeared in the law review's first volume in 1897. This edito- rial was entitled About the Moot Court and explained the function of the items published in the law review under the heading "Moot Court." This explanation is helpful because neither the Dickinson Law Review nor any other U.S. law review currently publishes any- thing that is comparable to these "moot court" items. The Editorial from Volume One described as follows the "moot court" process that preceded these publications: The moot court has for some time played a larger role in the Dickinson School of Law than in most other law schools, and during the year just closing it has received an emphasis never before put on it. -

1 Achieving a Fair and Effective COVID-19 Response

1 Achieving A Fair and Effective COVID-19 Response: An Open Letter to Vice-President Mike Pence, and Other Federal, State and Local Leaders from Public Health and Legal Experts in the United States Sustained human-to-human transmission of the novel coronavirus in the United States (US) appears today inevitable. The extent and impact of the outbreak in the US is difficult to predict and will depend crucially on how policymakers and leaders react. It will depend particularly on whether there is adequate funding and support for the response; fair and effective management of surging health care demand; careful and evidence-based mitigation of public fear; and necessary support and resources for fair and effective infection control. A successful American response to the COVID-19 pandemic must protect the health and human rights of everyone in the US. One of the greatest challenges ahead is to make sure that the burdens of COVID-19, and our response measures, do not fall unfairly on people in society who are vulnerable because of their economic, social, or health status. We write as experts in public health, law, and human rights, with experience in previous pandemic responses, to set forth principles and practices that should guide the efforts against COVID-19 in the US. It is essential that all institutions, public and private, address the following critical concerns through new legislation, institutional policies, leadership and spending. ADEQUATE FUNDING AND SUPPORT FOR THE RESPONSE MUST BE PROVIDED ● Federal, state and local governments should act immediately to allocate funds to ensure that necessary measures can be carried out and that basic human needs continue to be met as the epidemic unfolds. -

Penn State Dickinson Law Facilities

Policies, Safety & U 2020 ANNUAL SECURITY REPORT AND ANNUAL FIRE SAFETY REPORT Table of Contents From the President ............................................................................................................................. 5 From the Associate Vice President for University Police and Public Safety ........................................ 5 ANNUAL SECURITY REPORT PREPARATION OF THE ANNUAL SECURITY REPORT AND DISCLOSURE OF CRIME 6 STATISTICS ....................................................................................................................................... ABOUT UNIVERSITY POLICE AND PUBLIC SAFETY ...................................................................... 6 Safety, Our Number One Priority .......................................................................................... 6 Working Relationship with Local, State, and Federal Law Enforcement Agencies ................ 6 Crimes Involving Student Organizations at Off-Campus Locations ....................................... 7 REPORTING CRIMES AND OTHER EMERGENCIES ....................................................................... 7 Voluntary, Confidential Reporting ......................................................................................... 7 Reporting to University Police and Public Safety .................................................................. 7 Reporting to Other Campus Security Authorities .................................................................. 8 TIMELY WARNINGS ......................................................................................................................... -

Annual Report 2006

Centre Regional Planning Commission 2006 Annual Report Centre Region Act 537 Sewage Facilities Plan In 2006, the Centre Regional Planning Agency (CRPA) staff worked with the Centre Region mu- nicipalities and the Ad Hoc Act 537 Committee to develop a consensus on an updated Regional Sewage Facilities Plan. This Plan was adopted by the six Centre Region municipalities in October 2006. The 2006 Centre Region Act 537 Sewage Facilities Plan includes an updated Regional Growth Boundary/Sewer Service Area (RGB/SSA). Five new properties were added to the RGB/SSA in the 2006 Act 537 Update. During the preparation of this Plan, the Region’s municipalities also reached consensus on an Implementation Agreement which provides a process for considering future requests to expand the RGB/SSA. The Plan defines these future RGB/SSA expan- sion requests and major rezonings within the RGB/SSA as Developments of Regional Impact (DRI) which require in- Inside: creased regional review. This DRI process will increase in- termunicipal dialogue on important land use planning issues 2006 Accomplishments 2 in the community. Director’s Message 3 The adopted Centre Region Act 537 Plan has been Stream Buffer Model Ordinance 4 submitted to the Pennsylvania Department of Environ- Sewage Management Ordinance 4 mental Protection for review and comment. The DEP’s comments on this regional plan are expected by the end of Area Land Use Plans 5 April, 2007. Development Plans Reviewed in 2006 6 2007 Objectives 10 Affordable/Workforce Housing 10 Transportation Activities 11 Who We Are 13 Staff News 13 CENTRE REGIONAL PLANNING COMMISSION Page 2 2006 Accomplishments Development Ordinance. -

Distributor Settlement Agreement

DISTRIBUTOR SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT Table of Contents Page I. Definitions............................................................................................................................1 II. Participation by States and Condition to Preliminary Agreement .....................................13 III. Injunctive Relief .................................................................................................................13 IV. Settlement Payments ..........................................................................................................13 V. Allocation and Use of Settlement Payments ......................................................................28 VI. Enforcement .......................................................................................................................34 VII. Participation by Subdivisions ............................................................................................40 VIII. Condition to Effectiveness of Agreement and Filing of Consent Judgment .....................42 IX. Additional Restitution ........................................................................................................44 X. Plaintiffs’ Attorneys’ Fees and Costs ................................................................................44 XI. Release ...............................................................................................................................44 XII. Later Litigating Subdivisions .............................................................................................49 -

Lucille Johnston-Walsh

LUCY JOHNSTON-WALSH Penn State Dickinson Law 45 N. Pitt Street Carlisle, PA 17013 (717) 243-2968 [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE PENN STATE DICKINSON LAW 2002-present Clinical Professor, Director of Children’s Advocacy Clinic, Director of Center on Children and the Law 2005 to present Supervising Attorney Family Law Clinic & Disability Law Clinic 2002-2005 MIDPENN LEGAL SERVICES 2001-2002 Staff Attorney PENNSYLVANIA PARTNERSHIPS FOR CHILDREN 1997-2001 Director of Public Policy STAFFORD COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS, VA 1989-1994 School Social Worker EDUCATION Penn State Dickinson Law, Juris Doctor, 1997 University of Pennsylvania, Master of Social Work, 1989 Juniata College, Bachelor of Science, 1987 SELECTED PUBLICATIONS “Tele-Lawyering and The Virtual Learning Experience: Finding the Silver Lining for Remote Hybrid Externships & Law Clinics after the Pandemic,” AKRON LAW REVIEW, Forthcoming 2021. “Kinship Care in Pennsylvania: Creating an Equitable System for Families,” White Paper with ABA Center on Children and the Law, Community Legal Services, Juvenile Law Center, Temple Legal Aid Officeand Pennsylvania Partnerships for Children, February 2021. “Life is a Highway: Addressing Legal Obstacles to Foster Youth Driving,” SEATTLE JOURNAL FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE, Vol. 19, Issue 1, December 2020. 1 Assisted in passage of House Bill 1615; Act 16-2019 – “Fostering Independence Tuition Waiver Program,” signed by Governor Wolf June 28, 2019 “Behind the Wheel: Driving as a Route to Independence for Foster Youth,” White Paper for Annie E. Casey Foundation, State Policy Advocacy and Reform Center, September 2018. “The Unreasonably Uncertain Risks of ‘Reasonable Medical Certainty’ in Child Abuse Cases: Mechanisms for Risk Reduction,” along with Carrie Russell, Mark S. -

Robert D. Richards

ROBERT D. RICHARDS John & Ann Curley Professor of First Amendment Studies The Pennsylvania State University College of Communications 308 James Building (814) 863-1900 University Park, PA 16802 E-mail: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Academic August 1988 The Pennsylvania State University to Present College of Communications John & Ann Curley Professor of First Amendment Studies Primary responsibilities include teaching, research and service in the areas of First Amendment and mass media law, media and government, news media ethics and broadcast journalism. February 1992 Pennsylvania Center for the First Amendment to Present (Founded February 1992) School of Communications Founder and Co-Director Primary responsibilities include directing and coordinating a citizen's resource center devoted to providing a heightened awareness of First Amendment freedoms. July 1997 The Penn State Washington Program To Present Founding Director Primary responsibilities include development and oversight of the administration and curriculum of the University’s educational programming in Washington, D.C. July 1999 The Pennsylvania State University to August 2003 College of Communications Associate Dean for Undergraduate Education and Faculty Development Primary responsibilities include oversight of the undergraduate programs in the College, including budget, scheduling, curriculum, advising, student radio station (WKPS) and shared responsibility for promotion and tenure issues. July 2000 Interim Head, Department of Journalism to July 2002 Primary responsibilities include supervision of curricular issues related to the journalism program and personnel matters involving journalism faculty. July 1999 The Pennsylvania State University to May 2000 College of Communications Interim Associate Dean for Undergraduate Education Primary responsibilities include oversight of the undergraduate programs in the College, including budget, scheduling, curriculum, advising, and shared responsibilities for faculty development. -

Penn State's Dickinson

EVENTS NEWS NOVEMBER 2019 TUESDAY SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT AUGUST 1 12 MATTHEW J.B. LAWRENCE JOINS DICKINSON LAW 3456789 FACULTY 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 August 1, 2017 — Matthew J.B. Lawrence has joined the faculty of Penn State’s Dickinson Law as assistant professor of law. An expert in 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 the fields of health law and administrative law, Lawrence will teach Health Care Law and Policy, Health Law: Business Organization and Finance, Health Care Entrepreneurship and Administrative Law. Professor Lawrence will work with Assistant Professor of Law Medha Makhlouf to develop the health law program at Dickinson Law— including the joint degree program with the Department of Public Health Sciences at Penn State College of Medicine and the Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, a partnership between Penn State Harrisburg, Dickinson Law, and the College of Medicine. “Matthew brings a wealth of health law expertise to Dickinson Law,” said Gary S. Gildin, dean, Dickinson Law. “He is an accomplished scholar who I know will share both his practical experiences and policy and theoretical perspectives that are critical to preparing students for practice in the evolving field of health law.” As an academic fellow and lecturer on law at Harvard Law School’s Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Bioethics and Biotechnology, Lawrence conducted independent research and prepared legal scholarship on health law issues, designed and taught a seminar at Harvard Law School entitled “Law and Medicine: The Affordable Care Act,” organized conferences and events exploring health reform, and mentored both law students and medical school students writing health law and policy scholarship.