Framing the Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright Jr.: a Comparative Analysis of Mainstream and Alternative Newspaper Coverage, 2007-2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marcia Hermansen, and Elif Medeni

CURRICULUM VITAE Marcia K. Hermansen October 2020 Theology Dept. Loyola University Crown Center 301 Tel. (773)-508-2345 (work) 1032 W. Sheridan Rd., Chicago Il 60660 E-mail [email protected] I. EDUCATION A. Institution Dates Degree Field University of Chicago 1974-1982 Ph.D. Near East Languages and Civilization (Arabic & Islamic Studies) University of Toronto 1973-1974 Special Student University of Waterloo 1970-1972 B.A. General Arts B. Dissertation Topic: The Theory of Religion of Shah Wali Allah of Delhi (1702-1762) C. Language Competency: Arabic, Persian, Urdu, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Dutch, Turkish II. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY A. Teaching and Other Positions Held 2006- Director, Islamic World Studies Program, Loyola 1997- Professor, Theology Dept., Loyola University, Chicago 2003 Visiting Professor, Summer School, Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium 1982-1997 Professor, Religious Studies, San Diego State University 1985-1986 Visiting Professor, Institute of Islamic Studies McGill University, Montreal, Canada 1980-1981 Foreign Service, Canadian Department of External Affairs: Postings to the United Nations General Assembly, Canadian Delegation; Vice-Consul, Canadian Embassy, Caracas, Venezuela 1979-1980 Lecturer, Religion Department, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario M. K. Hermansen—2 B.Courses Taught Religious Studies World Religions: Major concepts from eastern and western religious traditions. Religions of India Myth and Symbol: Psychological, anthropological, and religious approaches Religion and Psychology Sacred Biography Dynamics of Religious Experience Comparative Spiritualities Scripture in Comparative Perspective Ways of Understanding Religion (Theory and Methodology in the Study of Religion) Comparative Mysticism Introduction to Religious Studies Myth, Magic, and Mysticism Islamic Studies Introduction to Islam. Islamic Mysticism: A seminar based on discussion of readings from Sufi texts. -

Obama and the Black Political Establishment

“YOU MAY NOT GET THERE WITH ME …” 1 OBAMA & THE BLACK POLITICAL ESTABLISHMENT KAREEM U. CRAYTON Page | 1 One of the earliest controversies involving the now historic presidential campaign of Barack Obama was largely an unavoidable one. The issue beyond his control, to paraphrase his later comment on the subject, was largely woven into his DNA.2 Amidst the excitement about electing an African-American candidate to the presidency, columnist Debra Dickerson argued that this fervor might be somewhat misplaced. Despite his many appealing qualities, Dickerson asserted, Obama was not “black” in the conventional sense that many of his supporters understood him to be. While Obama frequently “invokes slavery and Jim Crow, he does so as one who stands outside, one who emotes but still merely informs.”3 Controversial as it was, Dickerson’s observation was not without at least some factual basis. Biologically speaking, for example, Obama was not part of an African- American family – at least in the traditional sense. The central theme of his speech at the 2004 Democratic convention was that only a place like America would have allowed his Kenyan father to meet and marry his white American mother during the 1960s.4 While 1 Special thanks to Vincent Brown, who very aptly suggested the title for this article in the midst of a discussion about the role of race and politics in this election. Also I am grateful to Meta Jones for her helpful comments and suggestions. 2 See Senator Barack Obama, Remarks in Response to Recent Statements b y Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright Jr. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA CABLE NEWS NETWORK, INC. and ABILIO JAMES ACOSTA, Plaintiffs, V

Case 1:18-cv-02610-TJK Document 6-1 Filed 11/13/18 Page 1 of 23 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CABLE NEWS NETWORK, INC. and ABILIO JAMES ACOSTA, Plaintiffs, v. DONALD J. TRUMP, in his official capacity as President of the United States; JOHN F. KELLY, in his official capacity as Chief of Staff to the President of the United States; WILLIAM SHINE, in his official capacity as Deputy Chief Case No. 1:18-cv-02610-TJK of Staff to the President of the United States; SARAH HUCKABEE SANDERS, in her official capacity as Press Secretary to the President of the United States; the UNITED STATES SECRET SERVICE; RANDOLPH ALLES, in his official capacity as Director of the United States Secret Service; and JOHN DOE, Secret Service Agent, in his official capacity, Defendants. BRIEF OF THE REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING PLAINTIFFS’ MOTIONS FOR A TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Case 1:18-cv-02610-TJK Document 6-1 Filed 11/13/18 Page 2 of 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................. i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................................................... ii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... -

The Trump Presidency, Journalism, and Democracy

The Trump Presidency, Journalism, and Democracy Edited by Robert E. Gutsche, Jr. First published 2018 ISBN 13:978-1-138-30738-4 (hbk) ISBN 13:978-1-315-14232-6 (ebk) Chapter 7 The Hell that Black People Live Trump’s Reports to Journalists on Urban Conditions Carolyn Guniss CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 7 The Hell that Black People Live Trump’s Reports to Journalists on Urban Conditions Carolyn Guniss It’s February 16, 2017. Donald J. Trump has been in the White House as Commander-in-Chief for just about a month. Trump holds a press conference to announce that he had nominated Alexander Acosta, a Hispanic man, as the U.S. Secretary of Labor. He uses the moment to update Americans about the “mess at home and abroad” that he inherited. He also took questions from journalists at his first press conference as president. Trump takes a question from April Ryan, a veteran White House cor- respondent for American Urban Radio Networks. She has been in that role since 1997, is in the process of covering her fourth U.S. president, and serves as the radio network’s Washington, D.C. bureau chief. Standing about midpoint, to the left of the room for the viewers, she signals to Trump that she wants to ask a question. Trump does what he does best when dealing with people of color: He finds a way to offend Ryan. “Yes, oh, this is going to be a bad question, but that’s OK,” he said. It is unclear what Trump meant by the statement, but whatever he meant, it wasn’t positive. -

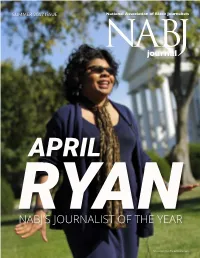

Nabj's Journalist of the Year

SUMMER 2017 ISSUE APRIL RYANNABJ’S JOURNALIST OF THE YEAR Permission from The Baltimore Sun B:8.75” T:7.75” S:7” #EbonyOwes SUMMER 2017 | Vol. 35, No. 2 Official Publication of the is the canary National Association of Black Journalists NABJ Staff INTERIM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR in the coal mine Shirley Carswell MEMBERSHIP MANAGER Veronique Dodson FINANCE MANAGER Nathaniel Chambers SENIOR PROJECT MANAGER Kerwin Speight PAGE DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANT 18 JoAnne Lyons Wooten DEVELOPMENT CONCIERGE Heidi Stevens PROJECT MANAGER Angela Robinson STAFF ACCOUNTANT Sharon Odle April Ryan is making history NABJ Journal Staff on the White House beat B:11.5” S:9.75” T:10.5” 6 PUBLISHER Sarah Glover EDITOR Zuri Berry DEPUTY EDITOR Shauntel Lowe Ron Thomas reinvented COPY EDITOR 12 himself as an educator Benét J. Wilson CIRCULATION MANAGER Veronique Dodson Contributors Danny Garrett This is what inspiring Autumn A. Arnett 20 black men looks like Marcus Vanderberg Johann Calhoun Cheryl Smith Gayle Hurd WINTER 2017 ISSUE SPIN YOUR OWN TALE. Correction: The fi rst-ever Toyota C-HR. A dynamic, new crossover with car-like handling. In the Winter 2017 NABJ Journal, we Plus, Toyota Safety Sense™ P1 comes standard to help you avoid danger incorrectly published who was the POWERED BY THE founding editor of Emerge Magazine. It on your way to Grandma’s or out on the town. BLACK PRESS was Wilmer C. Ames Jr. We apologize for Copyright 2017 How the new Museum of African the error. The National Association of American History and Culture pays homage to black journalists Black Journalists Prototype shown with options. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Marcia K. Hermansen September 2020

CURRICULUM VITAE Marcia K. Hermansen September 2020 Theology Dept. Loyola University Crown Center 301 Tel. (773)-508-2345 (work) 1032 W. Sheridan Rd., Chicago Il 60660 E-mail [email protected] I. EDUCATION A. Institution Dates Degree Field University of Chicago 1974-1982 Ph.D. Near East Languages and Civilization (Arabic & Islamic Studies) University of Toronto 1973-1974 Special Student University of Waterloo 1970-1972 B.A. General Arts B. Dissertation Topic: The Theory of Religion of Shah Wali Allah of Delhi (1702-1762) C. Language Competency: Arabic, Persian, Urdu, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Dutch, Turkish II. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY A. Teaching and Other Positions Held 2006- Director, Islamic World Studies Program, Loyola 1997- Professor, Theology Dept., Loyola University, Chicago 2003 Visiting Professor, Summer School, Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium 1982-1997 Professor, Religious Studies, San Diego State University 1985-1986 Visiting Professor, Institute of Islamic Studies McGill University, Montreal, Canada 1980-1981 Foreign Service, Canadian Department of External Affairs: Postings to the United Nations General Assembly, Canadian Delegation; Vice-Consul, Canadian Embassy, Caracas, Venezuela 1979-1980 Lecturer, Religion Department, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario M. K. Hermansen—2 B.Courses Taught Religious Studies World Religions: Major concepts from eastern and western religious traditions. Religions of India Myth and Symbol: Psychological, anthropological, and religious approaches Religion and Psychology Sacred Biography Dynamics of Religious Experience Comparative Spiritualities Scripture in Comparative Perspective Ways of Understanding Religion (Theory and Methodology in the Study of Religion) Comparative Mysticism Introduction to Religious Studies Myth, Magic, and Mysticism Islamic Studies Introduction to Islam. Islamic Mysticism: A seminar based on discussion of readings from Sufi texts. -

June 2015 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data

June 2015 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data June 7, 2015 23 men and 7 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 0 men and 0 women None CBS's Face the Nation with John Dickerson: 6 men and 2 women Gov. Chris Christie (M) Mayor Bill de Blasio (M) Fmr. Gov. Rick Perry (M) Rep. Michael McCaul (M) Jamelle Bouie (M) Nancy Cordes (F) Ron Fournier (M) Susan Page (F) ABC's This Week with George Stephanopoulos: 6 men and 1 woman Gov. Scott Walker (M) Ret. Gen. Stanley McChrystal (M) Donna Brazile (F) Matthew Dowd (M) Newt Gingrich (M) Robert Reich (M) Michael Leiter (M) CNN's State of the Union with Candy Crowley: 5 men and 3 women Sen. Lindsey Graham (M) Fmr. Gov. Rick Perry (M) Sen. Joni Ernst (F) Sen. Tom Cotton (M) Fmr. Gov. Lincoln Chafee (M) Jennifer Jacobs (F) Maeve Reston (F) Matt Strawn (M) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: 6 men and 1 woman Fmr. Sen. Rick Santorum (M) Rep. Peter King (M) Rep. Adam Schiff (M) Brit Hume (M) Sheryl Gay Stolberg (F) George Will (M) Juan Williams (M) June 14, 2015 30 men and 15 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 4 men and 8 women Carly Fiorina (F) Jon Ralston (M) Cathy Engelbert (F) Kishanna Poteat Brown (F) Maria Shriver (F) Norwegian P.M Erna Solberg (F) Mat Bai (M) Ruth Marcus (F) Kathleen Parker (F) Michael Steele (M) Sen. Dianne Feinstein (F) Michael Leiter (M) CBS's Face the Nation with John Dickerson: 7 men and 2 women Fmr. -

National Press Club Speaker Breakfast with the Reverend Dr

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB SPEAKER BREAKFAST WITH THE REVEREND DR. JEREMIAH WRIGHT, SENIOR PASTOR OF THE TRINITY UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS TOPIC: THE AFRICAN-AMERICAN RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE MODERATOR: DONNA LEINWAND, REPORTER, USA TODAY, AND VICE PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 9:00 A.M. EDT DATE: MONDAY, APRIL 28, 2008 (C) COPYRIGHT 2005, FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC., 1000 VERMONT AVE. NW; 5TH FLOOR; WASHINGTON, DC - 20005, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. IS A PRIVATE FIRM AND IS NOT AFFILIATED WITH THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. NO COPYRIGHT IS CLAIMED AS TO ANY PART OF THE ORIGINAL WORK PREPARED BY A UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT OFFICER OR EMPLOYEE AS PART OF THAT PERSON'S OFFICIAL DUTIES. FOR INFORMATION ON SUBSCRIBING TO FNS, PLEASE CALL JACK GRAEME AT 202-347-1400. ------------------------- MS. LEINWAND: Good morning. Good morning, and welcome to the National Press Club for our speaker breakfast featuring Reverend Jeremiah Wright. My name is Donna Leinwand. I'm the vice president of the National Press Club and a reporter for USA Today. I'd like to welcome club members and their guests in the audience today, as well as those of you watching on C-SPAN. And I -- we have many, many guests here today. We're looking forward to today's speech, and afterwards I will ask as many questions as time permits. -

Interview with Jimmy Carter Larry King Live (Transcript) April 28, 2008

Interview with Jimmy Carter Larry King Live (Transcript) April 28, 2008 LARRY KING, HOST: Tonight, Jimmy Carter. His controversial Mideast peace efforts draws slams from the Bush administration and Israel -- and a shout-out from the Reverend Jeremiah Wright. (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) JEREMIAH WRIGHT, BARACK OBAMA'S FORMER PASTOR: The same thing now that President Carter is being vilified for. (END VIDEO CLIP) KING: What drives him to go where no former president has ever gone before? And if he can't broker peace overseas, can he help the Obama and the Clinton campaign forces stop fighting here? As he made his presidential pick, Jimmy Carter standing up, speaking out. And then, Barack Obama's former pastor preaches his point of view, but not in church. (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) WRIGHT: I served six years in the military. Does that make me patriotic? How many years did Cheney serve? (END VIDEO CLIP) KING: Does more talk from Reverend Wright mean more trouble for a divided Democratic Party? It's all next on LARRY KING LIVE. We've got a terrific book from the 39th president of the United States, this one "A Remarkable Mother". It's published by Simon & Schuster. And there you see its cover. I'll be talking to the president about his wonderful mother in a little while. But, of course, some thoughts are -- bear discussion right off the top. What do you see as the impact of Reverend Wright on this presidential campaign? JIMMY CARTER, FORMER PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES: Transient. I don't think it's going to be anything permanent or damaging. -

Negotiating News at the White House

"Enemy of the People": Negotiating News at the White House CAROL PAULI* I. INTRODUCTION II. WHITE HOUSE PRESS BRIEFINGS A. PressBriefing as Negotiation B. The Parties and Their Power, Generally C. Ghosts in the Briefing Room D. Zone ofPossibleAgreement III. THE NEW ADMINISTRATION A. The Parties and Their Power, 2016-2017 B. White House Moves 1. NOVEMBER 22: POSITIONING 2. JANUARY 11: PLAYING TIT-FOR-TAT a. Tit-for-Tat b. Warning or Threat 3. JANUARY 21: ANCHORING AND MORE a. Anchoring b. Testing the Press c. Taunting the Press d. Changingthe GroundRules e. Devaluing the Offer f. MisdirectingPress Attention * Associate Professor, Texas A&M University School of Law; J.D. Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law; M.S. Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism; former writer and editor for the Associated Press broadcast wire; former writer and producer for CBS News; former writer for the Evansville (IN) Sunday Courier& Press and the Decatur (IL) Herald-Review. I am grateful for the encouragement and generosity of colleagues at Texas A&M University School of Law, especially Professor Cynthia Alkon, Professor Susan Fortney, Professor Guillermo Garcia, Professor Neil Sobol, and Professor Nancy Welsh. I also appreciate the helpful comments of members of the AALS section on Dispute Resolution, particularly Professor Noam Ebner, Professor Caroline Kaas, Professor David Noll, and Professor Richard Reuben. Special thanks go to longtime Associated Press White House Correspondent, Mark Smith, who kindly read a late draft of this article, made candid corrections, and offered valuable observations from his experience on the front lines (actually, the second row) of the White House press room. -

Downloads, Distributed Freedom Professor Abigail Thompson, Chair of Nearly 30,000 Printed Copies, and Have Gone Into

Then & Now ACTA’s 25-Year Drive to Restore the Promise of Higher Education ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Stephen Joel Trachtenberg Sidney L. Gulick III Board of Directors President Emeritus and University Professor Emeritus Professor of Mathematics, University of Maryland Edwin D. Williamson, Esq., Chairman of Public Service, The George Washington University Robert “KC” Johnson Partner, Sullivan & Cromwell, LLP (ret.) Michael B. Poliakoff, Ph.D. Professor of History, CUNY–Brooklyn College Robert T. Lewit, M.D., Treasurer President, ACTA (ex-officio) Anatoly M. Khazanov CEO, Metropolitan Psychiatric Group (ret.) Ernest Gellner Professor of Anthropology Emeritus, John D. Fonte, Ph.D., Secretary & Asst. Treas. Council of Scholars University of Wisconsin; Fellow, British Academy Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute George E. Andrews Alan Charles Kors John W. Altman Evan Pugh University Professor of Mathematics, Henry Charles Lea Professor Emeritus of History, Entrepreneur Pennsylvania State University University of Pennsylvania Former Trustee, Miami University Mark Bauerlein Jon D. Levenson George “Hank” Brown Emeritus Professor of English, Emory University Albert A. List Professor of Jewish Studies, Harvard Divinity School Former U.S. Senator Marc Zvi Brettler Former President, University of Colorado Bernice and Morton Lerner Distinguished Professor of Molly Levine Janice Rogers Brown Judaic Studies, Duke University Professor of Classics, Howard University Former Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals, D.C. Cir. William Cook George R. Lucas, Jr. Former Justice of the California Supreme Court Emeritus Distinguished Teaching Professor and Emeritus Senior Fellow, Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership, Jane Fraser Professor of History, SUNY–Geneseo United States Naval Academy President, Stuttering Foundation of America Paul Davies Joyce Lee Malcolm Heidi Ganahl Professor of Philosophy, College of William & Mary Professor Emerita of Law, George Mason University Fellow of the Royal Historical Society Founder, SheFactor & Camp Bow Wow David C. -

MICHELLE OBAMA: You Come Into This House and There Is So Much to Do, There's So Much Coming at You That There's No Time to Think Or Reflect…

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) MICHELLE OBAMA: You come into this house and there is so much to do, there's so much coming at you that there's no time to think or reflect… OBAMA: Hi everyone we are here digging up soil because we're about to plant a garden. OBAMA: I won't be satisfied nor will my husband until every single veteran and military spouse who wants a job has one. OBAMA: At the end of the day my most important title is still mom-in-chief. (END VIDEO CLIP) SUSAN SWAIN: In 2008 Barack Obama was elected as our 44th president and he and first lady Michelle Obama went into the history books as the first African American first couple. Now one year into a second Obama term, the first lady continues her focus on childhood obesity, support for military families and access to education. Good evening and welcome. Well tonight is the final installment in our yearlong series First Ladies: Influence and Image, and we finish appropriately with the current first lady Michelle Obama. For the next 90 minutes, we'll learn more about her biography and how she's approached the job in her six years in the office so far. Let me introduce you to our two guests who'll be here with us throughout that time and they're both journalists who have covered the first lady. Liza Mundy is a biographer of Michelle Obama; her 2008 book was called "Michelle." And Krissah Thompson is a "Washington Post" journalist who covers the first lady as her beat, thanks for coming both of you tonight.