The Trump Presidency, Journalism, and Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA CABLE NEWS NETWORK, INC. and ABILIO JAMES ACOSTA, Plaintiffs, V

Case 1:18-cv-02610-TJK Document 6-1 Filed 11/13/18 Page 1 of 23 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CABLE NEWS NETWORK, INC. and ABILIO JAMES ACOSTA, Plaintiffs, v. DONALD J. TRUMP, in his official capacity as President of the United States; JOHN F. KELLY, in his official capacity as Chief of Staff to the President of the United States; WILLIAM SHINE, in his official capacity as Deputy Chief Case No. 1:18-cv-02610-TJK of Staff to the President of the United States; SARAH HUCKABEE SANDERS, in her official capacity as Press Secretary to the President of the United States; the UNITED STATES SECRET SERVICE; RANDOLPH ALLES, in his official capacity as Director of the United States Secret Service; and JOHN DOE, Secret Service Agent, in his official capacity, Defendants. BRIEF OF THE REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING PLAINTIFFS’ MOTIONS FOR A TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Case 1:18-cv-02610-TJK Document 6-1 Filed 11/13/18 Page 2 of 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................. i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................................................... ii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... -

Gone Rogue: Time to Reform the Presidential Primary Debates

Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series #D-67, January 2012 Gone Rogue: Time to Reform the Presidential Primary Debates by Mark McKinnon Shorenstein Center Reidy Fellow, Fall 2011 Political Communications Strategist Vice Chairman Hill+Knowlton Strategies Research Assistant: Sacha Feinman © 2012 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. How would the course of history been altered had P.T. Barnum moderated the famed Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858? Today’s ultimate showman and on-again, off-again presidential candidate Donald Trump invited the Republican presidential primary contenders to a debate he planned to moderate and broadcast over the Christmas holidays. One of a record 30 such debates and forums held or scheduled between May 2011 and March 2012, this, more than any of the previous debates, had the potential to be an embarrassing debacle. Trump “could do a lot of damage to somebody,” said Karl Rove, the architect of President George W. Bush’s 2000 and 2004 campaigns, in an interview with Greta Van Susteren of Fox News. “And I suspect it’s not going to be to the candidate that he’s leaning towards. This is a man who says himself that he is going to run— potentially run—for the president of the United States starting next May. Why do we have that person moderating a debate?” 1 Sen. John McCain of Arizona, the 2008 Republican nominee for president, also reacted: “I guarantee you, there are too many debates and we have lost the focus on what the candidates’ vision for America is.. -

Ellen L. Weintraub

2/5/2020 FEC | Commissioner Ellen L. Weintraub Home › About the FEC › Leadership and Structure › All Commissioners › Ellen L. Weintraub Ellen L. Weintraub Democrat Currently serving CONTACT Email [email protected] Twitter @EllenLWeintraub Biography Ellen L. Weintraub (@EllenLWeintraub) has served as a commissioner on the U.S. Federal Election Commission since 2002 and chaired it for the third time in 2019. During her tenure, Weintraub has served as a consistent voice for meaningful campaign-finance law enforcement and robust disclosure. She believes that strong and fair regulation of money in politics is important to prevent corruption and maintain the faith of the American people in their democracy. https://www.fec.gov/about/leadership-and-structure/ellen-l-weintraub/ 1/23 2/5/2020 FEC | Commissioner Ellen L. Weintraub Weintraub sounded the alarm early–and continues to do so–regarding the potential for corporate and “dark-money” spending to become a vehicle for foreign influence in our elections. Weintraub is a native New Yorker with degrees from Yale College and Harvard Law School. Prior to her appointment to the FEC, Weintraub was Of Counsel to the Political Law Group of Perkins Coie LLP and Counsel to the House Ethics Committee. Top items The State of the Federal Election Commission, 2019 End of Year Report, December 20, 2019 The Law of Internet Communication Disclaimers, December 18, 2019 "Don’t abolish political ads on social media. Stop microtargeting." Washington Post, November 1, 2019 The State of the Federal Election -

Does American Democracy Still Work?

Does American Democracy Still Work? Does American Democracy Still Work? ?ALAN WOLFE Yale University Press New Haven and London The Future of American Democracy series aims to examine, sustain, and renew the historic vision of American democracy in a series of books by some of America’s foremost thinkers. The books in the series present a new, balanced, centrist approach to examining the challenges American democracy has faced in the past and must overcome in the years ahead. Series editor: Norton Garfinkle. Copyright © 2006 by Alan Wolfe. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Minion type by Integrated Publishing Solutions, Grand Rapids, Michigan. Printed in the United States of America by R. R. Donnelley, Harrisonburg, Virginia. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wolfe, Alan, 1942– Does American democracy still work? / Alan Wolfe. p. cm.—(The future of American democracy) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-300-10859-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-300-10859-1 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Democracy—United States. 2. United States—Politics and government. I. Title. II. Series JK1726.W65 2006 320.973—dc22 2006008116 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. -

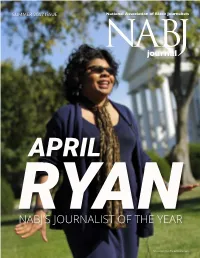

Nabj's Journalist of the Year

SUMMER 2017 ISSUE APRIL RYANNABJ’S JOURNALIST OF THE YEAR Permission from The Baltimore Sun B:8.75” T:7.75” S:7” #EbonyOwes SUMMER 2017 | Vol. 35, No. 2 Official Publication of the is the canary National Association of Black Journalists NABJ Staff INTERIM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR in the coal mine Shirley Carswell MEMBERSHIP MANAGER Veronique Dodson FINANCE MANAGER Nathaniel Chambers SENIOR PROJECT MANAGER Kerwin Speight PAGE DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANT 18 JoAnne Lyons Wooten DEVELOPMENT CONCIERGE Heidi Stevens PROJECT MANAGER Angela Robinson STAFF ACCOUNTANT Sharon Odle April Ryan is making history NABJ Journal Staff on the White House beat B:11.5” S:9.75” T:10.5” 6 PUBLISHER Sarah Glover EDITOR Zuri Berry DEPUTY EDITOR Shauntel Lowe Ron Thomas reinvented COPY EDITOR 12 himself as an educator Benét J. Wilson CIRCULATION MANAGER Veronique Dodson Contributors Danny Garrett This is what inspiring Autumn A. Arnett 20 black men looks like Marcus Vanderberg Johann Calhoun Cheryl Smith Gayle Hurd WINTER 2017 ISSUE SPIN YOUR OWN TALE. Correction: The fi rst-ever Toyota C-HR. A dynamic, new crossover with car-like handling. In the Winter 2017 NABJ Journal, we Plus, Toyota Safety Sense™ P1 comes standard to help you avoid danger incorrectly published who was the POWERED BY THE founding editor of Emerge Magazine. It on your way to Grandma’s or out on the town. BLACK PRESS was Wilmer C. Ames Jr. We apologize for Copyright 2017 How the new Museum of African the error. The National Association of American History and Culture pays homage to black journalists Black Journalists Prototype shown with options. -

June 2015 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data

June 2015 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data June 7, 2015 23 men and 7 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 0 men and 0 women None CBS's Face the Nation with John Dickerson: 6 men and 2 women Gov. Chris Christie (M) Mayor Bill de Blasio (M) Fmr. Gov. Rick Perry (M) Rep. Michael McCaul (M) Jamelle Bouie (M) Nancy Cordes (F) Ron Fournier (M) Susan Page (F) ABC's This Week with George Stephanopoulos: 6 men and 1 woman Gov. Scott Walker (M) Ret. Gen. Stanley McChrystal (M) Donna Brazile (F) Matthew Dowd (M) Newt Gingrich (M) Robert Reich (M) Michael Leiter (M) CNN's State of the Union with Candy Crowley: 5 men and 3 women Sen. Lindsey Graham (M) Fmr. Gov. Rick Perry (M) Sen. Joni Ernst (F) Sen. Tom Cotton (M) Fmr. Gov. Lincoln Chafee (M) Jennifer Jacobs (F) Maeve Reston (F) Matt Strawn (M) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: 6 men and 1 woman Fmr. Sen. Rick Santorum (M) Rep. Peter King (M) Rep. Adam Schiff (M) Brit Hume (M) Sheryl Gay Stolberg (F) George Will (M) Juan Williams (M) June 14, 2015 30 men and 15 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 4 men and 8 women Carly Fiorina (F) Jon Ralston (M) Cathy Engelbert (F) Kishanna Poteat Brown (F) Maria Shriver (F) Norwegian P.M Erna Solberg (F) Mat Bai (M) Ruth Marcus (F) Kathleen Parker (F) Michael Steele (M) Sen. Dianne Feinstein (F) Michael Leiter (M) CBS's Face the Nation with John Dickerson: 7 men and 2 women Fmr. -

Volume 34, No. 2

Picnic and Central Committee Meeting We lost the ballot access appeal; see the main www.MD.LP.org front page News section for various articles about it. It is impor- tant for everybody to go to our automated petition generation webpage (click the Petition link at the top left of the front page, or go directly to www.MD.LP.org/petition. We have a short time- frame to collect sufficient signatures to get our candidates back onto the November General Election ballot. You might believe that you already signed; enter your name on the petition webpage and it will tell you if we can still use your signature this time around. It is even more important for all of us to ask our friends and family members to sign the petition as well. Here is a sample email you might modify and send to everybody in your address book: Friends, I don’t usually send out political emails in case they’d be interpreted as unwanted spam. This is going to everyone in my address book, so I apologize if it is unwanted. But this is an urgent critical What: Libertarian Party of Maryland Annual Picnic case and the window of opportunity is short. IMHO Date: Saturday, July 28 (rain or shine) this is an egregious affront to the electoral pro- Location: 4626 River Rd., Bethesda, MD 20816 cess. Please take a few minutes and sign our peti- (Arvin Vohra’s home) tion at: Schedule: 2:00 pm: picnicking http://www.MD.LP.org/petition 4:00 pm: Central Committee meeting (no charge) It would be great if you’d forward either the web Cost: $8.00 mailed to Box 176 (or click credit cards on website) link or this email itself to your contacts in Mary- by July 23; $10.00 on site land. -

Notice of General Election

Notice of General Election Notice is hereby given that on Tuesday the 6th day of November, 2012 at the polling places in the election precincts of Clay County, Nebraska, the General Election will be held. The polls will open at 8:00 a.m. and close at 8:00 p.m. Said election will be for electing candidates to various offices. Some races will not appear on your General Election ballot as the candidates are elected by specific subdivisions, districts or wards. Proposed Amendments to the Constitution and Initiatives or Referendums will be published by the Secretary of State. Presidential Ticket Non-Partisan Ticket School Tickets Republican Mitt Romney Judge of the District Court District # 2 Sutton School Board President District One Sara Nuss Paul Ryan Shall Judge Vicky L. Johnson be retained Michael L. Thompson Vice President in office? Democrat District #90 Adams Central Central Community College Area Barack Obama School Board President Board of Governors Gaylord Johnson Joseph R. Biden Jr. First District Ryan Weeks Vice President Paul R. Krieger Karen L. Mousel Libertarian At Large Dave Lynn Gary Johnson Sam Cowan Carissa Uhrmacher President For Little Blue Natural Resource Chad E. Trausch James P. Gray District Director Vice President District #74 Blue Hill School Board Sub District One Americans Elect Lori Toepfer No filings No filings Michael Karr Sub District Two By Petition Dale Harrifeld Randall A. Terry Charles Rainforth President Sub District Three District # 47 Davenport School Marjorie Smith Jeremy Groves Board Vice President Sub District Four Ron Holeman Senatorial Ticket Ross A. Fisher Jeff Hoins Republican Sub District Five Rod Tegtmeier Deb Fischer Steven Shaw Democrat Sub District Six District #126 Doniphan Trumbull Bob Kerrey Sacha Lemke School Board Libertarian Sub District Seven Chris Sullivan No filings Alan D. -

Negotiating News at the White House

"Enemy of the People": Negotiating News at the White House CAROL PAULI* I. INTRODUCTION II. WHITE HOUSE PRESS BRIEFINGS A. PressBriefing as Negotiation B. The Parties and Their Power, Generally C. Ghosts in the Briefing Room D. Zone ofPossibleAgreement III. THE NEW ADMINISTRATION A. The Parties and Their Power, 2016-2017 B. White House Moves 1. NOVEMBER 22: POSITIONING 2. JANUARY 11: PLAYING TIT-FOR-TAT a. Tit-for-Tat b. Warning or Threat 3. JANUARY 21: ANCHORING AND MORE a. Anchoring b. Testing the Press c. Taunting the Press d. Changingthe GroundRules e. Devaluing the Offer f. MisdirectingPress Attention * Associate Professor, Texas A&M University School of Law; J.D. Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law; M.S. Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism; former writer and editor for the Associated Press broadcast wire; former writer and producer for CBS News; former writer for the Evansville (IN) Sunday Courier& Press and the Decatur (IL) Herald-Review. I am grateful for the encouragement and generosity of colleagues at Texas A&M University School of Law, especially Professor Cynthia Alkon, Professor Susan Fortney, Professor Guillermo Garcia, Professor Neil Sobol, and Professor Nancy Welsh. I also appreciate the helpful comments of members of the AALS section on Dispute Resolution, particularly Professor Noam Ebner, Professor Caroline Kaas, Professor David Noll, and Professor Richard Reuben. Special thanks go to longtime Associated Press White House Correspondent, Mark Smith, who kindly read a late draft of this article, made candid corrections, and offered valuable observations from his experience on the front lines (actually, the second row) of the White House press room. -

"Enemy of the People": Negotiating News at the White House

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 1-2018 "Enemy of the People": Negotiating News at the White House Carol Pauli Texas A&M University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Communications Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the President/ Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Carol Pauli, "Enemy of the People": Negotiating News at the White House, 33 Ohio St. J. Disp. Resol. 397 (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/1290 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Enemy of the People": Negotiating News at the White House CAROL PAULI* I. INTRODUCTION II. WHITE HOUSE PRESS BRIEFINGS A. PressBriefing as Negotiation B. The Parties and Their Power, Generally C. Ghosts in the Briefing Room D. Zone ofPossibleAgreement III. THE NEW ADMINISTRATION A. The Parties and Their Power, 2016-2017 B. White House Moves 1. NOVEMBER 22: POSITIONING 2. JANUARY 11: PLAYING TIT-FOR-TAT a. Tit-for-Tat b. Warning or Threat 3. JANUARY 21: ANCHORING AND MORE a. Anchoring b. Testing the Press c. Taunting the Press d. Changingthe GroundRules e. Devaluing the Offer f. MisdirectingPress Attention * Associate Professor, Texas A&M University School of Law; J.D. Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law; M.S. -

Equal Freedom Ii Equal Freedom

Equal Freedom ii Equal Freedom The Principle of Equal Freedom and Noncoercive Government Jerome L. Wright A Principled Basis for Free Societies Copyright © 2011 by Jerome L. Wright. All rights reserved. Foyle Publishing Foyle.co ii Table of Contents Preface Part 1 The Principle of Equal Freedom 1. The Concept of Equal Freedom 2. The Principle and Its Corollaries 3. Application in a Free Society 4. Application in a Controlled Society Part 2 The Individual in Equal Freedom 5. Rights and Properties 6. Living Without Coercion 7. Living Without Fraud 8. Living With Responsibility 9. Living With Equal Respect 10. Living in Liberty Part 3 The Role of Noncoercive Government 11. The Nature of Noncoercive Government 12. The Role of Government 13. Societal Services 14. The Societal System Part 4 The Functioning of Noncoercive Government 15. Operating Proprietary Governments 16. Clients and Government 17. Preparation 18. Implementation and Transition 19. A Civilization of Equal Freedom Bibliography Index iii PREFACE While there is a multitude of predecessors who have made a work such as this possible, these stand out in my mind as the most prominent builders of the theory of freedom: John Locke, Herbert Spencer, Gustave de Molinari, Lysander Spooner, Albert Jay Nock, Murray Rothbard, and Ludwig von Mises. Freedom is the ability to live your life as you wish to live it, with full control of your properties. Equal freedom means having your freedom while respecting the same freedom of others. No government on Earth today allows freedom, although many claim they do. It is possible to attain and maintain a society of freedom, but not an easy task on this world. -

Gov. Gary Johnson, Judge Jim Gray Top LP Ticket LP Top Gray Jim Judge Johnson, Gary Gov

WWW.LP.ORG MiniMuM GovernMent • MaxiMuM FreedoM The Party of Principle™ David Bergland Moderates Wrights/ Johnson Debate - Page 3 June 2012 The Official Newspaper of the Libertarian Party Volume 42, Issue 2 Voting Libertarian is the Only Cure for Big Government - Page 5 Winner of Libertarian Solutions Contest - Page 6 In This Issue: Chair’s Corner.............................2 LPGov. Gary Johnson, News Judge Jim Gray Top LP Ticket roller-coaster ride, a heart-rending LP Presidential Debate................3 celebration of the party’s 40-year A history, the election of our high- profile presidential and vice-presidential Bylaw Changes...........................3 candidates and a refreshing departure from today’s scripted, tightly controlled, and Convention News..................3-6,8 taxpayer-funded Republican and Demo- cratic conventions -- that was the 2012 Platform Changes.......................5 Libertarian National Convention held at the Red Rock Resort in Las Vegas, Nevada LP Candidates......................6-8,11 on May 2 to 6. The presidential debate between Lee Libertarian Solutions..............6,15 Wrights and Gary Johnson was as friendly as a reunion of two old friends. The presi- Awards.......................................8 dential and vice presidential nominations were decisive. The Libertarian Party elected former two-term New Mexico Governor Gary Johnson (left) as its presidential can- An array of Libertarian Heroes and diate for the 2012 election. Judge Jim Gray (right), a veteran trial judge in California, was elected Vice President. Gov. Gary Johnson Inverview......9 other fascinating speakers graced the con- Then came the election for party of- ian Presidential nominee, receiving 419 of vention with inspiring talks and powerful, ficers.