Fourth External Review Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6.C Board Practices Corporate Governance Framework

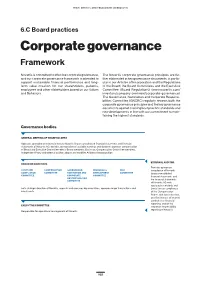

Item 6. Directors, Senior Management and Employees 6.C Board practices Corporate governance Framework Novartis is committed to effective corporate governance, The Novartis corporate governance principles are fur- and our corporate governance framework is intended to ther elaborated in key governance documents, in partic- support sustainable financial performance and long- ular in our Articles of Incorporation and the Regulations term value creation for our shareholders, patients, of the Board, the Board Committees and the Executive employees and other stakeholders based on our Values Committee (Board Regulations) (www.novartis.com/ and Behaviors. investors/company-overview/corporate-governance). The Governance, Nomination and Corporate Responsi- bilities Committee (GNCRC) regularly reviews both the corporate governance principles and the key governance documents against evolving best practice standards and new developments in line with our commitment to main- taining the highest standards. Governance bodies GENERAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS Approves operating and financial review, Novartis Group consolidated financial statements and financial statements of Novartis AG; decides appropriation of available earnings and dividend; approves compensation of Board and Executive Committee; elects Board members, Chairman, Compensation Committee members, Independent Proxy and external auditor; adopts and modifies Articles of Incorporation EXTERNAL AUDITOR BOARD OF DIRECTORS Provides opinion on AUDIT AND COMPENSATION GOVERNANCE, RESEARCH & RISK compliance -

Novartis in Society 2018 Report

Novartis in Society 2018 CONTENTS Novartis in Society 2018 | 2 Contents 2018 highlights 3 Who we are 4 What we do 6 Message from the CEO 8 Global Health & Corporate Responsibility at Novartis 9 Strategic areas 13 Holding ourselves to the highest ethical standards 13 Being part of the solution on pricing and access 18 Addressing global health challenges 29 Being a responsible citizen 35 About this report 46 Performance indicators 2018 47 Novartis GRI Content Index 51 Appendix: corporate responsibility material topic boundaries 55 Appendix: corporate responsibility materiality assessment issue cluster and topic definitions 56 Appendix: external initiatives and membership of associations 58 Appendix: supplier spend 2018 59 Appendix: measuring and valuing our impact 59 Independent Assurance Report on the Novartis 2018 corporate responsibility reporting 60 Cover photo Mukamudenge Melaniya, a potter living in rural Rwanda, receives treatment for malaria and other ailments at a local healthcare outpost run by a nurse entrepreneur and affiliated with One Family Health, a nongovernmental organization. 2018 HIGHLIGHTS Novartis in Society 2018 | 3 2018 highlights ETHICAL STANDARDS 54 % 100 + 220 REDUCTION PEOPLE COUNTRY VISITS in the number of reported complaints added to the Integrity & Compliance conducted by the Integrity & of fraud and professional practices in function in recent years Compliance function in 2018 the sales force in 2018 vs. 2017 ACCESS TO HEALTHCARE No. 2 24 m 17 m RANKING PATIENTS PEOPLE in the 2018 Access to Medicine Index, reached through access programs reached through training, up from third position in 2016 health education and service delivery programs GLOBAL HEALTH USD 100 m ~900 m 7.2 m INVESTMENT TREATMENT COURSES PATIENTS REACHED committed over the next five years to of Coartem delivered without with free multidrug therapy advance R&D of new antimalarials profit to date for leprosy since 1999 CORPORATE CITIZENSHIP No. -

Net FWD GLOBAL NETWORK of FOUNDATIONS WORKING for DEVELOPMENT MEMBERS

net FWD GLOBAL NETWORK OF FOUNDATIONS WORKING FOR DEVELOPMENT MEMBERS ENTERPRISE PHILANTHROPY Emirates Foundation for Youth Development (Abu Dhabi, UAE) Lundin Foundation (Vancouver, Canada) Rockefeller Foundation (NYC, USA) Shell Foundation (London, UK) INNOVATIVE THEMATIC PHILANTHROPY Centre d’Appui à la Jeunesse (CEDAJ) (Port-au-Prince, Haïti) The Edmond de Rothschild Foundations (Paris, France) Fundación Empresarial EuroChile (Santiago, Chile) Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian (Lisbon, Portugal) Instituto Ayrton Senna (São Paulo, Brazil) Mo Ibrahim Foundation (London, UK) Novartis Foundation for Sustainable Development (Basel, Switzerland) Olusegun Obasanjo Foundation* (London, UK) The African Capacity Building Foundation 1 (Harare, Zimbabwe) ASSOCIATES ASEAN Foundation (Jakarta, Indonesia) Asian Venture Philanthropy Network (AVPN) (Singapore) European Venture Philanthropy Association (EVPA) (Brussels, Belgium) Foundation Center (NYC, USA) John D. Gerhart Center for Philanthropy and Civic Engagement, American University in Cairo (New Cairo, Egypt) RedEAmérica (Bogota, Colombia) WINGS (São Paulo, Brazil) * Honorary member Development Centre OECD The OECD Development Centre (Dev) was established by The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development is decision of the OECD Council on 23 October 1962 and comprises a unique forum where governments work together to address the 24 member countries of the OECD: Austria, Belgium, Chile, the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to Israel, Italy, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, help governments respond to new developments and concerns, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the Switzerland, Turkey and the United Kingdom. In addition, the challenges of an ageing population. -

Download the Corporate Governance Chapter of the Annual

Item 6. Directors, Senior Management and Employees 6.C Board practices Corporate governance Framework Novartis is committed to effective corporate governance, The Novartis corporate governance principles are further and our corporate governance framework is intended to described in key governance documents, in particular in support sustainable financial performance and long- our Articles of Incorporation and the Regulations of term value creation for our shareholders, patients, the Board, the Board Committees and the Executive employees and other stakeholders based on our Values Committee (Board Regulations) (www.novartis.com/ and Behaviors. investors/company-overview/corporate-governance). The Governance, Nomination and Corporate Responsi- bilities Committee (GNCRC) regularly reviews both the corporate governance principles and the key governance documents against evolving best practice standards and new developments in line with our commitment to main- taining the highest standards. Governance bodies GENERAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS Approves operating and financial review, Novartis Group consolidated financial statements, and financial statements of Novartis AG; decides appropriation of available earnings and dividend; approves compensation of Board and Executive Committee; elects Board members, Chairman, Compensation Committee members, Independent Proxy and external auditor; adopts and modifies Articles of Incorporation EXTERNAL AUDITOR BOARD OF DIRECTORS Provides opinion on AUDIT AND COMPENSATION GOVERNANCE, RISK SCIENCE & compliance -

Novartis Corporate Responsibility Report 2017 | Contents 2

Corporate Responsibility Report 2017 Novartis Corporate Responsibility Report 2017 | CONTENTS 2 Contents 2017 HIGHLIGHTS 3 ABOUT NOVARTIS 5 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN 6 THREE QUESTIONS TO THE CEO AND THE GLOBAL HEAD OF CR 8 CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY AT NOVARTIS 10 Novartis and the UN Sustainable Development Goals 10 Governance of our corporate responsibility activities 10 Setting priorities – 2017 materiality assessment 11 Stakeholder engagement 13 Improving transparency 14 Financial, environmental and social impact valuation 14 ACCESS TO HEALTHCARE 17 Availability of medicines 19 Pricing 20 Intellectual property 21 Healthcare system strengthening 21 Patient assistance programs 23 INNOVATION 25 R&D for unmet medical needs 27 R&D for neglected diseases 27 Drug resistance 27 Business model innovation 28 Innovative technologies 29 PATIENT HEALTH AND SAFETY 30 Pharmacovigilance, safety profile and quality of drugs 31 Health education and prevention 32 Counterfeit medicines 34 ETHICAL BUSINESS PRACTICES 35 Ethical and compliant behavior 36 Responsible supply chain management 38 Respect for human rights 40 Responsible use of new technologies 41 Animal testing 42 ABOUT THIS REPORT 44 Performance indicators 2017 45 Novartis GRI Content Index 49 Appendix: external initiatives and membership of associations 55 Appendix: corporate responsibility issue cluster and topic definitions 56 Cover photo Adiarra Traore undergoes a Novartis and the United Nations Global Compact 58 health check at the Bougoula-Hameau clinic in Independent Assurance Report on the Novartis 2017 Mali, West Africa, as part of a clinical trial to corporate responsibility reporting 60 assess an experimental medicine for malaria called KAF156, being developed by Novartis and several partner organizations. Novartis Corporate Responsibility Report 2017 | 2017 highlighTS 3 2017 highlights ucts in the EU and launched them in several European markets. -

Download GHD-034 the Case of TTCIH

C ASES IN G LOBAL H EALTH D ELIVERY GHD-034 JANUARY 2016 Addressing Tanzania’s Health Workforce Crisis Through a Public-Private Partnership: The Case of TTCIH In early 2015, Senga Pemba was in his eighth year as director of the Tanzanian Training Centre for International Health (TTCIH), a public-private partnership between the Tanzanian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW), the Novartis Foundation, and the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in IfaKara, a small town in rural Tanzania. The founding organizations had created TTCIH to address the lacK of well-trained rural health care worKers in Tanzania, which was short 90,722 worKers in 2014. Pemba had invested in the organization’s protocols, procedures, and physical infrastructure and spent significant time mentoring and training staff members. TTCIH was now attracting over 500 students and graduating 50 assistant medical officers annually, and it was generating 80% of its own revenue. With his mandatory retirement approaching in two years, Pemba thought about his succession plan and what should come next for the organization amid a changing health education landscape. The TTCIH partners wanted the training center to be an independent enterprise, and Pemba had to think about how to position the organization for success. Overview of Tanzania The United Republic of Tanzania is located in Eastern Africa (see Exhibit 1 for map) and divided into 30 administrative regions. Less than one-third of its 51.8 million people lived in urban areas in 2014.1,2 In 2010, only 14% of the population had access to electricity,3 and 88% lacKed access to improved sanitation in 2014.4 Kimberly Sue, Julie Rosenberg, and Rebecca Weintraub prepared this case with assistance from Jennifer Goldsmith, Amy Madore, and Samantha Chao for the purposes of classroom discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective health care delivery practice. -

NOVARTIS AG (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on May 9, 2000 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F/A REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number 1- ɀ NOVARTIS AG (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) NOVARTIS Inc. (Translation of Registrant's name into English) Switzerland (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) Schwarzwaldallee 215 CH-4058 Basel Switzerland (Address of principal executive offices) Securities to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of class Name of each exchange on which registered American Depositary Shares New York Stock Exchange, Inc. each representing 1¤40 Ordinary Share, nominal value CHF 20 per Ordinary Share and Ordinary Shares* * Application to be made for listing, not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission. Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer's classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report: 72,130,117 Ordinary Shares Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended, during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days: Yes X No Not Applicable Indicate by check mark which financial statement item the Registrant has elected to follow: Item 17 Item 18 X INTRODUCTION Novartis AG and its consolidated subsidiaries (``Novartis'' or the ``Group'') publishes its consolidated financial statements expressed in Swiss francs (``CHF''). -

Novartis in Society ESG Report 2019 2 | Novartis in Society

Novartis in Society ESG Report 2019 2 | Novartis in Society Photo A worker at Zipline’s distribution center in Omenako, Ghana, prepares a Contents medical order for drone delivery. Novartis has partnered with Zipline, a US-based automated logistics company, to help deliver 2019 highlights 3 vital medicines to remote areas. Cover photo Patients at Kumasi General Who we are 4 Hospital in Ghana, where newborns are screened for sickle cell disease. Only about What we do 6 4% of babies in Ghana are tested for this debilitating genetic blood disorder. Message from the CEO 8 Global Health & Corporate Responsibility at Novartis 9 Strategic areas 13 Holding ourselves to the highest ethical standards 13 Being part of the solution on pricing and access 20 Addressing global health challenges 32 Being a responsible citizen 39 About this report 50 Performance indicators 2019 51 Novartis GRI Content Index 55 Appendix: corporate responsibility material topic boundaries 59 Appendix: corporate responsibility materiality assessment issue cluster and topic definitions 61 Appendix: external initiatives and membership of associations 63 Appendix: supplier spend 2019 64 Appendix: the responsible procurement (RP) risk indicator tool 64 Appendix: measuring and valuing our impact 65 Independent Assurance Report on the 2019 Novartis in Society ESG reporting 66 2019 HIGHLIGHTS Novartis in Society | 3 2019 highlights ETHICAL STANDARDS 99/100 500+ 135 SCORE ASSOCIATES HIGH-LEVEL AUDITS achieved by Novartis for clinical trial volunteered to be part of the performed -

Novartis-Annual-Report-2015-En.Pdf

Annual Report 2015 OUR MISSION Our mission is to discover new ways to improve and extend people’s lives. We use science-based innovation to address some of society’s most challenging healthcare issues. We discover and develop breakthrough treatments and find new ways to deliver them to as many people as possible. We also aim to provide a shareholder return that rewards those who invest their money, time and ideas in our company. PHOTO ESSAYS BRINGING HEALTHCARE HOME FIGHTING THE BIGGEST KILLER PRIMING THE BODY’S OWN DEFENSES Switzerland’s well-developed network of OF YOUNG CHILDREN AGAINST CANCER home healthcare workers is helping cope An army of health workers is guarding Scientists are developing a new with an aging population. Bangladeshi children from the deadly personalized T-cell therapy that scourge of pneumonia. could alter the course of cancer care. p STORY STARTS ON PAGE 13 p STORY STARTS ON PAGE 23 p STORY STARTS ON PAGE 43 THE CHALLENGE OF REVERSING THE IMPROVING ACCESS TO HEALTHCARE MAKING CLEAR VISION A PERSONAL RISE IN OBESITY IN RURAL VIETNAM MISSION A weight reduction program in one The rise of chronic disease will require Volunteer surgeons are bringing US state is helping tackle the growing getting more medicines to more people the gift of sight to some of the world’s problem of obesity. in less-developed countries. poorest people. p STORY STARTS ON PAGE 75 p STORY STARTS ON PAGE 109 p STORY STARTS ON PAGE 139 Novartis Annual Report 2015 | 1 CONTENTS 02 CHAIRMAN’S LETTER 04 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S LETTER 06 KEY PERFORMANCE -

TWAS Packard

Ifakara Health Institute IFAKIARA,HTANZANIA I EXCELLENCE IN SCIENCE Profiles of Research Institutions in Developing Countries PUBLISHED BY TWAS, THE ACADEMY OF SCIENCES FOR THE DEVELOPING WORLD EXCELLENCE IN SCIENCE Profiles of Research Institutions in Developing Countries EXCELLENCE IN SCIENCE Profiles of Research Institutions in Developing Countries Published by TWAS, the academy of sciences for the developing world ICTP Campus, Strada Costiera 11, 34151 Trieste, Italy tel: +39 040 2240327, fax: +39 040 224559 e-mail: [email protected], website: www.twas.org TWAS Executive Director Mohamed H.A. Hassan TWAS Public Information Office Daniel Schaffer, Gisela Isten, Tasia Asakawa, Brian Smith Design & Art Direction Studio Link, Trieste (www.studio-link.it) Printing Stella Arti Grafiche, Trieste This text may be reproduced freely with due credit to the source. Ifakara Health Institute IIFAKARHA, TANZANII A EXCELLENCE IN SCIENCE Profiles of Research Institutions in Developing Countries TWAS COUNCIL President Jacob Palis (Brazil) Immediate Past President C.N.R. Rao (India) Vice-Presidents Jorge E. Allende (Chile) Bai Chunli (China) Romain Murenzi (Rwanda) Atta-ur-Rahman (Pakistan) Ismail Serageldin (Egypt) Secretary General Dorairajan Balasubramanian (India) Treasurer José L. Morán López (Mexico) Council Members Ali A. Al-Shamlan (Kuwait) Eugenia M. del Piño Veintimilla (Ecuador) Reza Mansouri (Iran) Frederick I.B. Kayanja (Uganda) Keto E. Mshigeni (Tanzania) Abdul H. Zakri (Malaysia) Katepalli R. Sreenivasan (ex-officio member ) Foreword For the past decade, TWAS, the academy of sciences for the developing world , in collaboration with several other organizations and funding agencies – including the Unit ed Nations Development Programme’s Special Unit for South-South Cooperation (UNDP-SSC), the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the Packard Foundation – has developed a large number of profiles of scientific institutions of excellence in the devel - oping world. -

Using Technology to Advance Global Health: Proceedings of a Workshop

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/24882 SHARE Using Technology to Advance Global Health: Proceedings of a Workshop DETAILS 96 pages | 6 x 9 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-46477-2 | DOI 10.17226/24882 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Rachel M. Taylor and Joe Alper, Rapporteurs; Forum on Public-Private Partnerships for Global Health and Safety; Board on Global Health; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine FIND RELATED TITLES Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Using Technology to Advance Global Health: Proceedings of a Workshop USING TECHNOLOGY TO ADVANCE GLOBAL HEALTH PROCEEDINGS OF A WORKSHOP Rachel M. Taylor and Joe Alper, Rapporteurs Forum on Public—Private Partnerships for Global Health and Safety Board on Global Health Health and Medicine Division Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Using Technology to Advance Global Health: Proceedings of a Workshop THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES -

Novartis in Society Report 2018

UNCTAD Illicit Trade Forum 3rd to 4th February 2020 Room XXVI, Palais des Nations, Geneva Report - Novartis in Society Contribution by Novartis The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNCTAD Novartis in Society 2018 CONTENTS Novartis in Society 2018 | 2 Contents 2018 highlights 3 Who we are 4 What we do 6 Message from the CEO 8 Global Health & Corporate Responsibility at Novartis 9 Strategic areas 13 Holding ourselves to the highest ethical standards 13 Being part of the solution on pricing and access 18 Addressing global health challenges 29 Being a responsible citizen 35 About this report 46 Performance indicators 2018 47 Novartis GRI Content Index 51 Appendix: corporate responsibility material topic boundaries 55 Appendix: corporate responsibility materiality assessment issue cluster and topic definitions 56 Appendix: external initiatives and membership of associations 58 Appendix: supplier spend 2018 59 Appendix: measuring and valuing our impact 59 Independent Assurance Report on the Novartis 2018 corporate responsibility reporting 60 Cover photo Mukamudenge Melaniya, a potter living in rural Rwanda, receives treatment for malaria and other ailments at a local healthcare outpost run by a nurse entrepreneur and affiliated with One Family Health, a nongovernmental organization. 2018 HIGHLIGHTS Novartis in Society 2018 | 3 2018 highlights ETHICAL STANDARDS 54 % 100 + 220 REDUCTION PEOPLE COUNTRY VISITS in the number of reported complaints added to the Integrity & Compliance conducted by the Integrity & of fraud and professional practices in function in recent years Compliance function in 2018 the sales force in 2018 vs. 2017 ACCESS TO HEALTHCARE No.