Formulaic Diction in Kazakh Epic Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MLA In-Text Citations

1 MLA In-Text Collin College–Frisco, Lawler Hall 141 972-377-1080 ▪ [email protected] Citations Appointments: collin.mywconline.net Short Quotations Prose: Less than four (4) typed lines of prose is considered to be a short quotation. • Quotations should always be incorporated into a sentence of your original prose. A quotation should never stand alone in a sentence. • Follow each quotation with a parenthetical in-text citation containing: o Author’s last name (unless the author is introduced in your sentence) o Page number from which the quotation was taken. • The period comes after the parenthetical citation. A question mark or exclamation point should be placed within the quotation if it is part of the quoted section, with a period following the parenthetical citation. Example: According to John Brown, the writing center proves to be a “calm and quiet area to learn more about writing techniques” (22). Poetry: Three (3) lines or less of a poem is a short quotation. • In the parenthetical citation, use line number(s) instead of page numbers • The first time you quote a poem, use the word “line” or “lines.” In subsequent references, only include the actual line numbers. • Indicate each line break with a slash (/), placing a space both before and after it. • Use two slashes to indicate a stanza break. • A verse play, such as those written by Shakespeare, follows the rules for poetry. Example: The closing lines of Frost’s poem have a sleepy, dream-like quality: “The only other sound’s the sweep / Of easy wind and downy flake // The woods are lovely, dark and deep” (lines 11-13). -

Introduction to Meter

Introduction to Meter A stress or accent is the greater amount of force given to one syllable than another. English is a language in which all syllables are stressed or unstressed, and traditional poetry in English has used stress patterns as a fundamental structuring device. Meter is simply the rhythmic pattern of stresses in verse. To scan a poem means to read it for meter, an operation whose noun form is scansion. This can be tricky, for although we register and reproduce stresses in our everyday language, we are usually not aware of what we’re going. Learning to scan means making a more or less unconscious operation conscious. There are four types of meter in English: iambic, trochaic, anapestic, and dactylic. Each is named for a basic foot (usually two or three syllables with one strong stress). Iambs are feet with an unstressed syllable, followed by a stressed syllable. Only in nursery rhymes to do we tend to find totally regular meter, which has a singsong effect, Chidiock Tichborne’s poem being a notable exception. Here is a single line from Emily Dickinson that is totally regular iambic: _ / │ _ / │ _ / │ _ / My life had stood – a loaded Gun – This line serves to notify readers that the basic form of the poem will be iambic tetrameter, or four feet of iambs. The lines that follow are not so regular. Trochees are feet with a stressed syllable, followed by an unstressed syllable. Trochaic meter is associated with chants and magic spells in English: / _ │ / _ │ / _ │ / _ Double, double, toil and trouble, / _ │ / _ │ / _ │ / _ Fire burn and cauldron bubble. -

Poetry That Expresses Thoughts and Emotions of a Single Speaker

Type of writing done in verse form that Poetry uses figures of speech designed to appeal to emotions and imagination Poetry that expresses Lyric Poetry thoughts and emotions of a single speaker Poetry that tells a story Narrative Poetry Form and Structure Poem that is song-like; usually focuses Ballad on topics such as romance, adventure, and death; and tells a story Sonnet 14 line lyric poem A mourning poem; written for Elegy someone who has died Lyric poem on a serious subject; usually Ode addressed to one person or thing; often celebrates something a repeated sound, word, Refrain phrase, line, or group of lines Japanese 3 lined poem with 5 Haiku syllables in lines 1 and 3 and 7 syllables in line 2 Couplet two consecutive lines of poetry that rhyme Triplets Three lined stanza Quatrains 4 line stanzas poetry that doesn’t have a set Free Verse rhyme scheme or meter A very long narrative poem that tells of Epic the life and journeys of a hero A group of consecutive lines in a Stanza poem that forms a single unit; like paragraphs Figurative Language comparison between two unlike Simile things, using a word such as like, as, than, or resembles comparison between two unlike things that does not use a Metaphor connecting word a group of words not meant to Idiom be taken literally overstating something, usually Hyperbole for the purpose of creating a comic effect giving human characteristics to Personification an object or an animal contradictory elements (two Oxymoron things that do not belong together) use of language that appeals to Imagery -

The Waste Land by T

The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot Copyright Notice ©1998−2002; ©2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design® and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. ©2007 eNotes.com LLC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. For complete copyright information on these eNotes please visit: http://www.enotes.com/waste−land/copyright Table of Contents 1. The Waste Land: Introduction 2. Text of the Poem 3. T. S. Eliot Biography 4. Summary 5. Themes 6. Style 7. Historical Context 8. Critical Overview 9. Essays and Criticism 10. Topics for Further Study 11. Media Adaptations 12. What Do I Read Next? 13. Bibliography and Further Reading 14. Copyright Introduction Because of his wide−ranging contributions to poetry, criticism, prose, and drama, some critics consider Thomas Sterns Eliot one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century. The Waste Land can arguably be cited as his most influential work. When Eliot published this complex poem in 1922—first in his own literary magazine Criterion, then a month later in wider circulation in the Dial— it set off a critical firestorm in the literary world. The work is commonly regarded as one of the seminal works of modernist literature. Indeed, when many critics saw the poem for the first time, it seemed too modern. -

The Verse Dramas of TS Eliot

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1959 Search for form| the verse dramas of T. S. Eliot Carol Sue Rometch The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Rometch, Carol Sue, "Search for form| the verse dramas of T. S. Eliot" (1959). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3500. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3500 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SEARCH FOR FORM; THE VERSE DRAMAS OF T.S. ELIOT by CAROL SUE ROMETCH B.A. Whitman College, 1957 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1959 Approved by; GhfiHrman, Boàrd of Examiners Dean, Graduate School WAY 2 8 1959 Date UMI Number: EP35735 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ütaMitatton PlAMiing UMI EP35735 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Quoting Literature –Basic MLA Rules

QUOTING LITERATURE: Basic MLA Rules Prepared by Dr. Mira Sakrajda, Professor, English Department, Westchester Community College ______________________________________________________________ I. POETRY When you quote poetry, pay close attention to the poem’s original division into lines. If you quote one line of a poem, incorporate it into your sentence, using quotation marks and the line number in parentheses. If the quote ends your sentence, place the period after the parenthetical reference, not before it. From an essay on William Blake’s “The Clod and the Pebble”: Having focused on the selflessness of love in the first stanza, Blake challenges the reader’s understanding of this concept by saying that “Love seeketh only self to please” (9). If you quote two to three lines, add slash marks, with a space on either side, to indicate line division. From an essay on Emily Dickinson’s “Much Madness is divinest Sense –”: Dickinson draws a sharp contrast between society’s treatment of conformists and nonconformists: “Assent – and you are sane. / Demure – you are straightway dangerous and handled with a chain” (6-7). If you quote more than three lines, set the quote off one inch from the left margin (double the typical paragraph indent). The set-off quote should look like a perfect photocopy of the original in terms of layout, capitalization, and line division. Do not use quotation marks for a set-off quote, but do indicate line numbers in parentheses after the quote. From an essay on Robert Frost’s “Birches”: I have two children, three part-time jobs and four mid-terms next week, but I love my life and I totally identify with the speaker of “Birches” when he says: I’d like to get away from earth awhile And then come back to it and begin over. -

Waiting for Godot and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead Axel KRUSI;

SYDNEY STUDIES Tragicomedy and Tragic Burlesque: Waiting for Godot and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead AxEL KRUSI; When Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead appeared at the .Old Vic theatre' in 1967, there was some suspicion that lack of literary value was one reason for the play's success. These doubts are repeated in the revised 1969 edition of John Russell Taylor's standard survey of recent British drama. The view in The Angry Theatre is that Stoppard lacks individuality, and that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is a pale imitation of the theatre of the absurd, wrillen in "brisk, informal prose", and with a vision of character and life which seems "a very small mouse to emerge from such an imposing mountain".l In contrast, Jumpers was received with considerable critical approval. Jumpers and Osborne's A Sense of Detachment and Storey's Life Class might seem to be evidence that in the past few years the new British drama has reached maturity as a tradition of dramatic forms aitd dramatic conventions which exist as a pattern of meaningful relationships between plays and audiences in particular theatres.2 Jumpers includes a group of philosophical acrobats, and in style and meaning seems to be an improved version of Stoppard's trans· lation of Beckett's theatre of the absurd into the terms of the conversation about the death of tragedy between the Player and Rosencrantz: Player Why, we grow rusty and you catch us at the very point of decadence-by this time tomorrow we might have forgotten every thing we ever knew. -

Literary Forms-The Epic

Literary Forms-The Epic Dr.M.K.Praseeda Assistant Professor Department of English(Aided) The Epic • The Epic Defined:- • 1. Long narrative poem heroic personages of history or tradition. • 2. Tale in verse • Epic of Growth and Epic of Art:- • Epic is divided into two classes (1) The Epic of Growth or Authentic Epic or folk Epic. (2) The literary Epic or Epic of Art. • Authentic Epic is not the work of one man. • It is the collection of a series of folk songs and legends. • The literary Epic is the work of one individual genius • The old English epic “Beowulf”, Homer’s ‘Iliad’ is odyssey are Authentic Epics. • Vergil’s “Aeneid” and Milton’s paradise Lost” Literary Epic. Qualities of an epic:- • High seriousness. • Comprehensiveness. • Characterized by greatness of scope and majesty. • There is room four very great variety. • The action of epic is spacious. • Inclusiveness is another characteristic of an epic. • The characters are gods to ordinary mortals. • Its scenic background changes frequently. • Its takes long time. • The events therein range from the earth. • Choric aspect is a characteristic of an epic, which is mentioned by profession Tillyard. • Epic must express the spirit of an age or nation and not merely the feelings and experiences of individuals. • Homes expresses the admiration of the people of his time for the heroic qualities. • An epic poet has the consciousness of being a prophet of his time. The Convention in the Epic:- • (a) The theme of the Epic, is stated in the first few lines • The prayer and the ‘innovation’. • (b) Introduction of smilies in the Homeric manner. -

Virginian Writers Fugitive Verse

VIRGIN IAN WRITERS OF FUGITIVE VERSE VIRGINIAN WRITERS FUGITIVE VERSE we with ARMISTEAD C. GORDON, JR., M. A., PH. D, Assistant Proiesso-r of English Literature. University of Virginia I“ .‘ '. , - IV ' . \ ,- w \ . e. < ~\ ,' ’/I , . xx \ ‘1 ‘ 5:" /« .t {my | ; NC“ ‘.- ‘ '\ ’ 1 I Nor, \‘ /" . -. \\ ' ~. I -. Gil-T 'J 1’: II. D' VI. Doctor: .. _ ‘i 8 » $9793 Copyrighted 1923 by JAMES '1‘. WHITE & C0. :To MY FATHER ARMISTEAD CHURCHILL GORDON, A VIRGINIAN WRITER OF FUGITIVE VERSE. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. The thanks of the author are due to the following publishers, editors, and individuals for their kind permission to reprint the following selections for which they hold copyright: To Dodd, Mead and Company for “Hold Me Not False” by Katherine Pearson Woods. To The Neale Publishing Company for “1861-1865” by W. Cabell Bruce. To The Times-Dispatch Publishing Company for “The Land of Heart‘s Desire” by Thomas Lomax Hunter. To The Curtis Publishing Company for “The Lane” by Thomas Lomax Hunter (published in The Saturday Eve- ning Post, and copyrighted, 1923, by the Curtis Publishing 00.). To the Johnson Publishing Company for “Desolate” by Fanny Murdaugh Downing (cited from F. V. N. Painter’s Poets of Virginia). To Harper & Brothers for “A Mood” and “A Reed Call” by Charles Washington Coleman. To The Independent for “Life’s Silent Third”: by Charles Washington Coleman. To the Boston Evening Transcript for “Sister Mary Veronica” by Nancy Byrd Turner. To The Century for “Leaves from the Anthology” by Lewis Parke Chamberlayne and “Over the Sea Lies Spain” by Charles Washington Coleman. To Henry Holt and Company for “Mary‘s Dream” by John Lowe and “To Pocahontas” by John Rolfe. -

Poetry As Correspondence in Early Modern England

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Unfolding Verse: Poetry As Correspondence In Early Modern England Dianne Marie Mitchell University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Mitchell, Dianne Marie, "Unfolding Verse: Poetry As Correspondence In Early Modern England" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2477. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2477 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2477 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unfolding Verse: Poetry As Correspondence In Early Modern England Abstract This project recovers a forgotten history of Renaissance poetry as mail. At a time when trends in English print publication and manuscript dissemination were making lyric verse more accessible to a reading public than ever before, writers and correspondents created poetic objects designed to reach individual postal recipients. Drawing on extensive archival research, “Unfolding Verse” examines versions of popular poems by John Donne, Ben Jonson, Mary Wroth, and others which look little like “literature.” Rather, these verses bear salutations, addresses, folds, wax seals, and other signs of transmission through the informal postal networks of early modern England. Neither verse letters nor “epistles,” the textual artifacts I call “letter-poems” proclaim their participation in a widespread social -

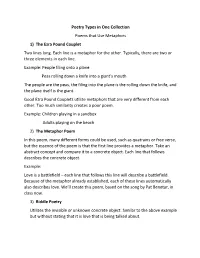

Poetry Types in One Collection Poems That Use Metaphors 1) the Ezra Pound Couplet Two Lines Long. Each Line Is a Metaphor for the Other

Poetry Types in One Collection Poems that Use Metaphors 1) The Ezra Pound Couplet Two lines long. Each line is a metaphor for the other. Typically, there are two or three elements in each line. Example: People filing onto a plane Peas rolling down a knife into a giant’s mouth The people are the peas, the filing into the plane is the rolling down the knife, and the plane itself is the giant. Good Ezra Pound Couplets utilize metaphors that are very different from each other. Too much similarity creates a poor poem. Example: Children playing in a sandbox Adults playing on the beach 2) The Metaphor Poem In this poem, many different forms could be used, such as quatrains or free verse, but the essence of the poem is that the first line provides a metaphor. Take an abstract concept and compare it to a concrete object. Each line that follows describes the concrete object. Example: Love is a battlefield – each line that follows this line will describe a battlefield. Because of the metaphor already established, each of these lines automatically also describes love. We’ll create this poem, based on the song by Pat Benetar, in class now. 3) Riddle Poetry Utilizes the invisible or unknown concrete object. Similar to the above example but without stating that it is love that is being talked about. Dylan Thomas portraits – this is a three line poem that asks a question which is answered by 4-6 word pairs ending in “ing”. Here is an example: Have you ever seen the rain? Life-giving, ground-soaking Mud-making, tires-spinning Haiku – Japanese three line poem with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern. -

Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion

APPENDIX B Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion Latin poetry follows a strict rhythm based on the quantity of the vowel in each syllable. Each line of poetry divides into a number of feet (analogous to the measures in music). The syllables in each foot scan as “long” or “short” according to the parameters of the meter that the poet employs. A vowel scans as “long” if (1) it is long by nature (e.g., the ablative singular ending in the first declen- sion: puellā); (2) it is a diphthong: ae (saepe), au (laudat), ei (deinde), eu (neuter), oe (poena), ui (cui); (3) it is long by position—these vowels are followed by double consonants (cantātae) or a consonantal i (Trōia), x (flexibus), or z. All other vowels scan as “short.” A few other matters often confuse beginners: (1) qu and gu count as single consonants (sīc aquilam; linguā); (2) h does NOT affect the quantity of a vowel Bellus( homō: Martial 1.9.1, the -us in bellus scans as short); (3) if a mute consonant (b, c, d, g, k, q, p, t) is followed by l or r, the preced- ing vowel scans according to the demands of the meter, either long (omnium patrōnus: Catullus 49.7, the -a in patrōnus scans as long to accommodate the hendecasyllabic meter) OR short (prō patriā: Horace, Carmina 3.2.13, the first -a in patriā scans as short to accommodate the Alcaic strophe). 583 40-Irby-Appendix B.indd 583 02/07/15 12:32 AM DESIGN SERVICES OF # 157612 Cust: OUP Au: Irby Pg.