Elements of Poetry.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MLA In-Text Citations

1 MLA In-Text Collin College–Frisco, Lawler Hall 141 972-377-1080 ▪ [email protected] Citations Appointments: collin.mywconline.net Short Quotations Prose: Less than four (4) typed lines of prose is considered to be a short quotation. • Quotations should always be incorporated into a sentence of your original prose. A quotation should never stand alone in a sentence. • Follow each quotation with a parenthetical in-text citation containing: o Author’s last name (unless the author is introduced in your sentence) o Page number from which the quotation was taken. • The period comes after the parenthetical citation. A question mark or exclamation point should be placed within the quotation if it is part of the quoted section, with a period following the parenthetical citation. Example: According to John Brown, the writing center proves to be a “calm and quiet area to learn more about writing techniques” (22). Poetry: Three (3) lines or less of a poem is a short quotation. • In the parenthetical citation, use line number(s) instead of page numbers • The first time you quote a poem, use the word “line” or “lines.” In subsequent references, only include the actual line numbers. • Indicate each line break with a slash (/), placing a space both before and after it. • Use two slashes to indicate a stanza break. • A verse play, such as those written by Shakespeare, follows the rules for poetry. Example: The closing lines of Frost’s poem have a sleepy, dream-like quality: “The only other sound’s the sweep / Of easy wind and downy flake // The woods are lovely, dark and deep” (lines 11-13). -

Introduction to Meter

Introduction to Meter A stress or accent is the greater amount of force given to one syllable than another. English is a language in which all syllables are stressed or unstressed, and traditional poetry in English has used stress patterns as a fundamental structuring device. Meter is simply the rhythmic pattern of stresses in verse. To scan a poem means to read it for meter, an operation whose noun form is scansion. This can be tricky, for although we register and reproduce stresses in our everyday language, we are usually not aware of what we’re going. Learning to scan means making a more or less unconscious operation conscious. There are four types of meter in English: iambic, trochaic, anapestic, and dactylic. Each is named for a basic foot (usually two or three syllables with one strong stress). Iambs are feet with an unstressed syllable, followed by a stressed syllable. Only in nursery rhymes to do we tend to find totally regular meter, which has a singsong effect, Chidiock Tichborne’s poem being a notable exception. Here is a single line from Emily Dickinson that is totally regular iambic: _ / │ _ / │ _ / │ _ / My life had stood – a loaded Gun – This line serves to notify readers that the basic form of the poem will be iambic tetrameter, or four feet of iambs. The lines that follow are not so regular. Trochees are feet with a stressed syllable, followed by an unstressed syllable. Trochaic meter is associated with chants and magic spells in English: / _ │ / _ │ / _ │ / _ Double, double, toil and trouble, / _ │ / _ │ / _ │ / _ Fire burn and cauldron bubble. -

Language Arts: Poetic Devices

Language Arts: Poetic Devices Students will • Read The Story of the Opera • Listen to the online selection Eddie’s Song: “I’m Running Away” from The Bremen Town Musicians included with the lesson and read the lyrics along with the song • Complete and discuss the appropriate portions of the Activity Worksheets Copies for Each Student Lyric sheet for “I’m Running Away” and the selected Activity Worksheets Copies for the Teacher Answer Keys for Activity Worksheets Getting Ready Decide which section(s) of the worksheet you wish your group to complete. Prepare internet access for The Bremen Town Musicians online listening selections. Gather pens, pencils and additional writing paper as needed for your group. Introduction Read “The Story of the Opera” to your students. Give each student a copy of Eddie’s Song:“I’m Running Away” and have them read it aloud. After reading it through once, have the students listen to the song: http://www.operatales.com/bremen/Im-running-away.mp3 Review Depending on which Activity Worksheets your class will complete, use the Poetic Devices Sheet on page 6 to review parts of a poem, rhyme scheme, alliteration, metaphors, similes or foreshadowing with your students. Guided/Independent Practice Depending on your grade level, the ability of your students, and time constraints, you may choose to have students work as a whole class, in small groups, with a partner, or individually. Read the directions on the Activity Worksheet. Provide instruction and model the activity as needed. Have students complete the portion(s) of the Activity Worksheet you have chosen with opportunity for questions. -

Songs in Fixed Forms

Songs in Fixed Forms by Margaret P. Hasselman 1 Introduction Fourteenth century France saw the development of several well-defined song structures. In contrast to the earlier troubadours and trouveres, the 14th-century songwriters established standardized patterns drawn from dance forms. These patterns then set up definite expectations in the listeners. The three forms which became standard, which are known today by the French term "formes fixes" (fixed forms), were the virelai, ballade and rondeau, although those terms were rarely used in that sense before the middle of the 14th century. (An older fixed form, the lai, was used in the Roman de Fauvel (c. 1316), and during the rest of the century primarily by Guillaume de Machaut.) All three forms make use of certain basic structural principles: repetition and contrast of music; correspondence of music with poetic form (syllable count and rhyme); couplets, in which two similar phrases or sections end differently, with the second ending more final or "closed" than the first; and refrains, where repetition of both words and music create an emphatic reference point. Contents • Definitions • Historical Context • Character and Provenance, with reference to specific examples • Notes and Selected Bibliography Definitions The three structures can be summarized using the conventional letters of the alphabet for repeated sections. Upper-case letters indicate that both text and music are identical. Lower-case letters indicate that a section of music is repeated with different words, which necessarily follow the same poetic form and rhyme-scheme. 1. Virelai The virelai consists of a refrain; a contrasting verse section, beginning with a couplet (two halves with open and closed endings), and continuing with a section which uses the music and the poetic form of the refrain; and finally a reiteration of the refrain. -

The Waste Land by T

The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot Copyright Notice ©1998−2002; ©2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design® and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. ©2007 eNotes.com LLC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. For complete copyright information on these eNotes please visit: http://www.enotes.com/waste−land/copyright Table of Contents 1. The Waste Land: Introduction 2. Text of the Poem 3. T. S. Eliot Biography 4. Summary 5. Themes 6. Style 7. Historical Context 8. Critical Overview 9. Essays and Criticism 10. Topics for Further Study 11. Media Adaptations 12. What Do I Read Next? 13. Bibliography and Further Reading 14. Copyright Introduction Because of his wide−ranging contributions to poetry, criticism, prose, and drama, some critics consider Thomas Sterns Eliot one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century. The Waste Land can arguably be cited as his most influential work. When Eliot published this complex poem in 1922—first in his own literary magazine Criterion, then a month later in wider circulation in the Dial— it set off a critical firestorm in the literary world. The work is commonly regarded as one of the seminal works of modernist literature. Indeed, when many critics saw the poem for the first time, it seemed too modern. -

Quoting Literature –Basic MLA Rules

QUOTING LITERATURE: Basic MLA Rules Prepared by Dr. Mira Sakrajda, Professor, English Department, Westchester Community College ______________________________________________________________ I. POETRY When you quote poetry, pay close attention to the poem’s original division into lines. If you quote one line of a poem, incorporate it into your sentence, using quotation marks and the line number in parentheses. If the quote ends your sentence, place the period after the parenthetical reference, not before it. From an essay on William Blake’s “The Clod and the Pebble”: Having focused on the selflessness of love in the first stanza, Blake challenges the reader’s understanding of this concept by saying that “Love seeketh only self to please” (9). If you quote two to three lines, add slash marks, with a space on either side, to indicate line division. From an essay on Emily Dickinson’s “Much Madness is divinest Sense –”: Dickinson draws a sharp contrast between society’s treatment of conformists and nonconformists: “Assent – and you are sane. / Demure – you are straightway dangerous and handled with a chain” (6-7). If you quote more than three lines, set the quote off one inch from the left margin (double the typical paragraph indent). The set-off quote should look like a perfect photocopy of the original in terms of layout, capitalization, and line division. Do not use quotation marks for a set-off quote, but do indicate line numbers in parentheses after the quote. From an essay on Robert Frost’s “Birches”: I have two children, three part-time jobs and four mid-terms next week, but I love my life and I totally identify with the speaker of “Birches” when he says: I’d like to get away from earth awhile And then come back to it and begin over. -

Coalescence of Form and Content in Ali's English Ghazal: the Trauma Of

Global Regional Review (GRR) URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/grr.2019(IV-II).16 Coalescence of Form and Content in Ali’s English Ghazal: The Trauma of Kashmir in The Country without a Post Office Vol. IV, No. II (Spring 2019) | Page: 145 ‒ 155 | DOI: 10.31703/grr.2019(IV-II).16 p- ISSN: 2616-955X | e-ISSN: 2663-7030 | ISSN-L: 2616-955X Sabir Hussain* Pinkish Zahra† Ghulam Murtaza‡ This paper investigates the enunciation of meaning in the coalescence of form and content in the ghazals of Agha Abstract Shahid Ali. In the last decade of the twentieth-century escalation of political and civil clashes handicapped the social system in Kashmir; all the government institutions remained closed for months. Post offices were one of those institutions which remained shut and the letters piled on without finding reaching their addressees. In this backdrop Ali wrote the collection, The Country Without a Post Office, where Ali mourns the state oppression. This research explores through literary stylistics the chaos and trauma inextricably interwoven in the form-content synchronization in the English ghazals of this collection. The form and content of these ghazals have aptly enunciated the trauma of Kashmir. Although ghazals to-date have been sung to mourn the unrequited love and separation of lover yet Ali has given this a novel thematic dimension by incorporating the blood and shreds, cannons and sticks, and nostalgia and dreams. Key Words: Urdu Ghazal, English Ghazal, Chaos, Trauma, Kashmir, Literary stylistics Introduction Political and social chaos has misshapen the occupied Kashmir into a limbo resulting in the trauma of the generations of Kashmir. -

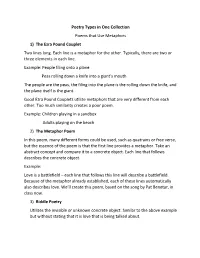

Poetry Types in One Collection Poems That Use Metaphors 1) the Ezra Pound Couplet Two Lines Long. Each Line Is a Metaphor for the Other

Poetry Types in One Collection Poems that Use Metaphors 1) The Ezra Pound Couplet Two lines long. Each line is a metaphor for the other. Typically, there are two or three elements in each line. Example: People filing onto a plane Peas rolling down a knife into a giant’s mouth The people are the peas, the filing into the plane is the rolling down the knife, and the plane itself is the giant. Good Ezra Pound Couplets utilize metaphors that are very different from each other. Too much similarity creates a poor poem. Example: Children playing in a sandbox Adults playing on the beach 2) The Metaphor Poem In this poem, many different forms could be used, such as quatrains or free verse, but the essence of the poem is that the first line provides a metaphor. Take an abstract concept and compare it to a concrete object. Each line that follows describes the concrete object. Example: Love is a battlefield – each line that follows this line will describe a battlefield. Because of the metaphor already established, each of these lines automatically also describes love. We’ll create this poem, based on the song by Pat Benetar, in class now. 3) Riddle Poetry Utilizes the invisible or unknown concrete object. Similar to the above example but without stating that it is love that is being talked about. Dylan Thomas portraits – this is a three line poem that asks a question which is answered by 4-6 word pairs ending in “ing”. Here is an example: Have you ever seen the rain? Life-giving, ground-soaking Mud-making, tires-spinning Haiku – Japanese three line poem with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern. -

Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion

APPENDIX B Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion Latin poetry follows a strict rhythm based on the quantity of the vowel in each syllable. Each line of poetry divides into a number of feet (analogous to the measures in music). The syllables in each foot scan as “long” or “short” according to the parameters of the meter that the poet employs. A vowel scans as “long” if (1) it is long by nature (e.g., the ablative singular ending in the first declen- sion: puellā); (2) it is a diphthong: ae (saepe), au (laudat), ei (deinde), eu (neuter), oe (poena), ui (cui); (3) it is long by position—these vowels are followed by double consonants (cantātae) or a consonantal i (Trōia), x (flexibus), or z. All other vowels scan as “short.” A few other matters often confuse beginners: (1) qu and gu count as single consonants (sīc aquilam; linguā); (2) h does NOT affect the quantity of a vowel Bellus( homō: Martial 1.9.1, the -us in bellus scans as short); (3) if a mute consonant (b, c, d, g, k, q, p, t) is followed by l or r, the preced- ing vowel scans according to the demands of the meter, either long (omnium patrōnus: Catullus 49.7, the -a in patrōnus scans as long to accommodate the hendecasyllabic meter) OR short (prō patriā: Horace, Carmina 3.2.13, the first -a in patriā scans as short to accommodate the Alcaic strophe). 583 40-Irby-Appendix B.indd 583 02/07/15 12:32 AM DESIGN SERVICES OF # 157612 Cust: OUP Au: Irby Pg. -

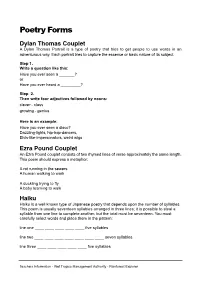

Poetry Forms Dylan Thomas Couplet a Dylan Thomas Portrait Is a Type of Poetry That Tries to Get People to Use Words in an Adventurous Way

Poetry Forms Dylan Thomas Couplet A Dylan Thomas Portrait is a type of poetry that tries to get people to use words in an adventurous way. Each portrait tries to capture the essence or basic nature of its subject. Step 1. Write a question like this: Have you ever seen a _______? or Have you ever heard a _________? Step 2. Then write four adjectives followed by nouns: clever - class growing - genius Here is an example: Have you ever seen a disco? Dazzling-lights, hip-hop-dancers, Elvis-like-impersonators, weird wigs Ezra Pound Couplet An Ezra Pound couplet consists of two rhymed lines of verse approximately the same length. This poem should express a metaphor: A rat running in the sewers A human walking to work A duckling trying to fly A baby learning to walk Haiku Haiku is a well known type of Japanese poetry that depends upon the number of syllables. This poem is usually seventeen syllables arranged in three lines; it is possible to steal a syllable from one line to complete another, but the total must be seventeen. You must carefully select words and place them in the pattern: line one ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ five syllables line two ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ seven syllables line three ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ five syllables Teachers Information - Wet Tropics Management Authority - Rainforest Explorer The first two lines should create a vivid picture and the third line should provide some insight into the picture. These poems should concern themselves with nature. Shape Poem This is a free-form poem published in the shape of something which exists in real life, in this instance it could be in the shape of a leaf, animal or buttress root. -

Shakespeare's Language

This document is designed as a resource for teachers which can be adapted to use with your students. Shakespeare's Language Introduction In Shakespeare's words lie all the clues to character and situation that any reader or actor needs. It's simply a matter of knowing how to find them. The clues are not necessarily in the meanings of the words - the rhythms of the language and the patterns and sounds of the words contain a great deal of valuable information. Here are some suggestions for finding the clues in Shakespeare's language: Blank verse Both written and spoken language use rhythm - a pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. Most forms of poetry or verse take rhythm one step further and regularise the rhythm into a formal pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. A formal pattern of rhythm is called metre. Shakespeare writes either in blank verse, in rhymed verse or in prose. Blank verse is unrhymed but uses a regular pattern of rhythm or metre. In the English language, blank verse is iambic pentameter. Pentameter means there are five poetic feet. In iambic pentameter each of these five feet is composed of two syllables: the first unstressed; the second stressed. The opening line of Twelfth Night, is a perfect iambic line : 'If music be the food of love play on' With its unstressed and stressed syllables marked or 'scanned', it looks like this: / ں / ں / ں / ں / ں 'If mu sic be the food of love play on' weak / = strong = ں The rhythm of blank verse is conversational and with its dee DUM, dee DUM, dee DUM, dee DUM, dee DUM rhythm, it imitates the heartbeat. -

Unfolding the Rondeau: Form and Meaning in Early 15Th-Century Chansons Elizabeth Randell Upton

Unfolding the Rondeau: Form and Meaning in Early 15th-century Chansons Elizabeth Randell Upton 1. Musicological Values and What Musicology Values It’s no longer news: much that 20th century musicologists considered to be objective and scientific, especially with regards to musical analysis, was rife with unexamined subjectivity. Since the early 1990s, scholars such as Rose Subotnik, Gary Tomlinson, Richard Taruskin, Lawrence Kramer and Susan McClary have uncovered and discussed what Janet M. Levy termed “Covert and casual values” in musicological writing. But much work still remains to be done. 2. The Formes Fixes Problem Discussions of the formes fixes chansons—ballades, rondeaux, and virelais—of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries clearly demonstrate how non-paradigmatic musical works can suffer when examined with 20th century analytical techniques developed to discuss 18th and 19th century German orchestral and instrumental music. Analysts of formes fixes chansons have tried to explain the appeal of these songs in “acceptable” terms: they found seed-like motives (especially in Machaut’s works) that grow throughout a piece, and they discussed the various ways a composer could unify a song into an organic whole. But nothing could be done to salvage the biggest problem with these songs: their formal structures, the defining element for us, are fixed. By definition, a formes fixes chanson can not develop, it “merely” repeats sections of music already heard, in some predetermined pattern. And, if the situation weren’t bad enough already, the poetry for these songs concerns itself mostly with what is generally seen as trite, stereotypical courtly love themes. Discussions of the formes fixes chansons in music history textbooks are largely taxonomies, concerned with describing the musical and poetic structures and documenting any variations.