Prosecutor Turf War Overshadows $150M Maxim Deal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amicus Brief

IN THE Superior Court of New Jersey NO. MER-L-1729-11 : GARDEN STATE EQUALITY; DANIEL WEISS and : MERCER COUNTY JOHN GRANT; MARSHA SHAPIRO and LOUISE : LAW DIVISION WALPIN; MAUREEN KILIAN and CINDY MENEGHIN; : SARAH KILIAN-MENEGHIN, a minor, by and through her : CIVIL ACTION guardians; ERICA and TEVONDA BRADSHAW; and : TEVERICO BARACK HAYES BRADSHAW, a minor, by : and through his guardians; MARCYE and KAREN : BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE IN NICHOLSON-McFADDEN; KASEY NICHOLSON- : SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ McFADDEN, a minor, by and through his guardians; MAYA : MOTION FOR SUMMARY NICHOLSON-McFADDEN, a minor, by and through her : JUDGMENT guardians; THOMAS DAVIDSON and KEITH HEIMANN; : AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES MARIE HEIMANN DAVIDSON, a minor, by and through : UNION OF NEW JERSEY her guardians; GRACE HEIMANN DAVIDSON, a minor, : by and through her guardians; ELENA and ELIZABETH : AMERICAN-ARAB ANTI- QUINONES; DESIREE NICOLE RIVERA, a minor, by : DISCRIMINATION and through her guardians; JUSTINE PAIGE LISA, a : COMMITTEE minor, by and through her guardians; PATRICK JAMES : ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL ROYLANCE, a minor, by and through his guardians; ELI : DEFENSE AND QUINONES, a minor, by and through his guardians, : EDUCATION FUND Plaintiffs-Appellants, : GARDEN STATE BAR : ASSOCIATION v. : HISPANIC BAR PAULA DOW, in her official capacity as Attorney General of : : ASSOCIATION OF NEW New Jersey; JENNIFER VELEZ, in her official capacity as JERSEY Commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Human : Services, and MARY E. O'DOWD, in her official capacity as : LEGAL MOMENTUM Commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Health and : NATIONAL ORGANIZATION Senior Services, : FOR WOMEN OF NEW : JERSEY Defendants-Respondents. : : RONALD K. -

United States Department of Justice U.S. Attorney, District of New Jersey 401 Market Street, Fourth Floor Camden, New Jersey 08101

NEWS United States Department of Justice U.S. Attorney, District of New Jersey 401 Market Street, Fourth Floor Camden, New Jersey 08101 Paul J. Fishman, U.S. Attorney More Information? Contact the Assistant U.S. Attorney or other contact listed below to see if more information is available. News on the Internet: News Releases, related documents and advisories are posted short-term at our website, along with links to our archived releases at the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. Go to: http://www.usdoj.gov/usao/nj/press/ Assistant U.S. Attorneys parry0319.rel KEVIN T. SMITH FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MATTHEW J. SKAHILL Mar. 19, 2010 SUSAN KASE 856-757-5026 Former Camden Police Officer Pleads Guilty to Conspiracy to Deprive Others of Their Civil Rights (More) Public Affairs Office 973-645-2888 Breaking News (NJ) http://www.usdoj.gov/usao/nj/press/ CAMDEN – A former Camden, New Jersey police officer pled guilty today to his role in a conspiracy with other Camden Police officers to deprive others of their civil rights, U.S. Attorney Paul J. Fishman announced. Kevin Parry, 29, admitted before U.S. District Judge Robert B. Kugler that from May 2007 until October 2009, while on duty as a uniformed police officer with the Camden Police Department, he engaged in a conspiracy with at least four other Camden Police officers to deprive persons in New Jersey of the free exercise and enjoyment of rights, privileges and immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States. The other officers were not identified by name. -

Turf War Stops at the ER - Los Angeles Times Page 1 of 5

Turf war stops at the ER - Los Angeles Times Page 1 of 5 Hello [email protected]... Profile Logout LAT Home | My LATimes | Print Edition | All Sections Jobs | Cars.com | Real Estate | Foreclosure Sale | More Classifieds SEARCH California | Local Crime Education Politics Environment Immigration Traffic O.C. Valley Inland Empire You are here: LAT Home > California | Local Turf war stops at the ER Email | Print | Text | RSS With an understanding of gang life born from his own past, Mike Garcia brings comfort ADVERTISEMENT to street combatants and peace to a Boyle Heights hospital. California/Local By Hector Becerra, Los Angeles Times Staff Writer May 4, 2007 Columnists: THE call came in just after 10 p.m. on a recent Monday. »Steve Lopez »Sandy Banks "Mike, we got a GSW." »Patt Morrison »George Skelton A gunshot wound. »Dana Parsons »Steve Harvey Mike Garcia hopped into his beat-up Mazda and drove to the emergency room at White »Steve Hymon Memorial Medical Center in Boyle Heights. He joined veteran nurse Eileen Powell beside a man on a gurney who had been shot multiple times at a local park. One of the Community Papers: bullets had shattered his thighbone into jagged halves just above the right knee. »Burbank »Newport Beach "Do we have any gang affiliation on him?" Powell asked Garcia. "I want to make sure » Laguna Beach whoever did this is not going to be coming by here to finish the job." »Huntington Beach »Glendale Six years ago, White Memorial Hospital looked for someone who could help the Most Viewed Most E-mailed hospital remain safe in a neighborhood where turf was claimed by some of Los News/Opinion 1. -

Environmental and Health Impacts of Artificial Turf: a Review

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259953859 Environmental and Health Impacts of Artificial Turf: A Review Article in Environmental Science & Technology · January 2014 Impact Factor: 5.33 · DOI: 10.1021/es4044193 · Source: PubMed CITATIONS READS 2 414 3 authors: Hefa Cheng Yuanan Hu Peking University China University of Geosciences (Beijing) 85 PUBLICATIONS 1,934 CITATIONS 39 PUBLICATIONS 1,061 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Martin Reinhard Stanford University 206 PUBLICATIONS 8,462 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Martin Reinhard Retrieved on: 18 May 2016 Critical Review pubs.acs.org/est Environmental and Health Impacts of Artificial Turf: A Review † † ‡ Hefa Cheng,*, Yuanan Hu, and Martin Reinhard † State Key Laboratory of Organic Geochemistry Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences Guangzhou 510640, China ‡ Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Stanford University Stanford, California 94305, United States *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: With significant water savings and low main- tenance requirements, artificial turf is increasingly promoted as a replacement for natural grass on athletic fields and lawns. However, there remains the question of whether it is an environmentally friendly alternative to natural grass. The major concerns stem from the infill material that is typically derived from scrap tires. Tire rubber crumb contains a range of organic contaminants and heavy metals that can volatilize into the air and/or leach into the percolating rainwater, thereby posing a potential risk to the environment and human health. A limited number of studies have shown that the concentrations of volatile and semivolatile organic compounds in the air above artificial turf fields were typically not higher than the local background, while the concentrations of heavy metals and organic contaminants in the field drainages were generally below the respective regulatory limits. -

2017 07-08 SPE 75Th Anniversary PE (Pdf) Download

Celebrating the world’s largest plastics technical society 19421942 -2017 and counting! COVER STORY Passion, Determination & a Focused Mission Helped Propel SPE on its Path 75 Years Ago It hasn’t been easy, but the world’s leading plastics technical society has endured, and remains true to its founders’ original goals By Robert Grace you've come a long way, baby. The 60 engineers who banded together in Detroit in January 1S94P2 – Ein t,he midst of World War II – to form a nonprofit organization to advance the knowledge of plastics could not have known that we’d be cele - brating their initiative 75 years later, or that the result of their efforts would be the largest plastics technical society in the world. But that is exactly the case. And the group’s Originally named the Society of Plas - rocky road in its early years and subsequent devel - tic Sales Engineers Inc., the group that opment often mirrored the challenges being felt would become the Society of Plastics by the country and the broader industry. It’s a fas - Engineers filed its Articles of Incorpora - cinating story that we are pleased to recap briefly tion on Jan. 6, 1942, in Michigan, with the here, with a focus on the group’s tumultuous first stated purpose of “cooperating, aiding, decade, along with some subsequent milestones. and effecting any commercial or indus - trial betterment pertaining to the The 1940s – in the beginning designing, styling, standardizing and pro - • 1942 – SPE was formed, and Fred O. Conley motion of the use of Plastics by the was elected president distribution of descriptive matter or per - • 1943 – the first ANTEC (in Detroit) and first sonal contact, or in convention in any RETEC (in Chicago) were held manner that may be educational.” • 1946 – the second ANTEC was a big success The group – which consisted of indi - • 1947 – the third ANTEC flopped and the vidual members, and initially charged $5 society nearly went bankrupt in annual dues – was the brainchild of • 1948 – SPE stabilized financially and moved Fred O. -

National Association of Women Judges Counterbalance Spring 2012 Volume 31 Issue 3

national association of women judges counterbalance Spring 2012 Volume 31 Issue 3 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Poverty’s Impact on the Administration of Justice / 1 President’s Message / 2 Executive Director’s Message / 3 Cambridge 2012 Midyear Meeting and Leadership Conference / 6 MEET ME IN MIAMI: NAWJ 2012 Annual Conference / 8 District News / 10 Immigration Programs News / 20 Membership Moments / 20 Women in Prison Report / 21 Louisiana Women in Prison / 21 Maryland Women in Prison / 23 NAWJ District 14 Director Judge Diana Becton and Contra Costa County native Christopher Darden with local high school youth New York Women in Prison / 24 participants in their November, 2011 Color of Justice program. Read more on their program in District 14 News. Learn about Color of Justice in creator Judge Brenda Loftin’s account on page 33. Educating the Courts and Others About Sexual Violence in Unexpected Areas / 28 NAWJ Judicial Selection Committee Supports Gender Equity in Selection of Judges / 29 POVERTY’S IMPACT ON THE ADMINISTRATION Newark Conference Perspective / 30 OF JUSTICE 1 Ten Years of the Color of Justice / 33 By the Honorable Anna Blackburne-Rigsby and Ashley Thomas Jeffrey Groton Remembered / 34 “The opposite of poverty is justice.”2 These words have stayed with me since I first heard them Program Spotlight: MentorJet / 35 during journalist Bill Moyers’ interview with civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson. In observance News from the ABA: Addressing Language of the anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, they were discussing what Dr. Access / 38 King would think of the United States today in the fight against inequality and injustice. -

Before the Education Practices Commission of the State of Florida

Before the Education Practices Commission of the State of Florida RICHARD CORCORAN, Commissioner of Education, Petitioner, vs. EPC CASE No. 20-0130-RT Index No. 21-094-FOF DOAH CASE No. 20-2075PL TYRHON RENARD CRAWFORD, PPS No. 178-2613 CERTIFICATE No. 878903 Respondent. / Final Order This matter was heard by a Teacher Panel of the Education Practices Commission pursuant to Sections 1012.795, 1012.796 and 120.57(1), Florida Statutes, on April 9, 2021 in Tallahassee, Florida, via video conference, for consideration of the Recommended Order entered in this case ELIZABETH W. MCARTHUR, Administrative Law Judge. Respondent was not present and was represented by Carol Buxton, Esquire. Petitioner was represented by Robert Ehrhardt, Esquire and Ron Weaver, Esquire. Findings of Fact 1 1. The findings of fact set forth in the Recommended Order are approved and adopted and incorporated herein by reference. 2. There is competent substantial evidence to support the findings of fact. Conclusions of Law 3. The Education Practices Commission has jurisdiction of this matter pursuant to Section 120.57(1), Florida Statutes, and Chapter 1012, Florida Statutes. 4. The conclusions of law set forth in the Recommended Order are approved and adopted and incorporated herein by reference. Penalty Upon a complete review of the record in this case, the Commission determines that the Recommended Order issued by the Administrative Law Judge be ACCEPTED. It is therefore ORDERED that: 5. Respondent’s certificate is hereby SUSPENDED for three (3) years from the date of this Final Order. 6. Upon employment in any public or private position requiring a Florida educator’s certificate, Respondent shall be placed on three (3) employment years of probation with the conditions that during that period, the Respondent shall: a. -

Primetime • Tuesday, April 17, 2012 Early Morning

Section C, Page 4 THE TIMES LEADER—Princeton, Ky.—April 14, 2012 PRIMETIME • TUESDAY, APRIL 17, 2012 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 ^ 9 Eyewitness News Who Wants to Be a Last Man Standing (7:31) Cougar Town Dancing With the Stars (N) (S) (Live) (9:01) Private Practice Erica’s medical Eyewitness News Nightline (N) (CC) (10:55) Jimmy Kimmel Live “Dancing WEHT at 6pm (N) (CC) Millionaire (CC) (N) (CC) (N) (CC) (CC) condition gets worse. (N) (CC) at 10pm (N) (CC) With the Stars”; Ashanti. (N) (CC) # # News (N) (CC) Entertainment To- Last Man Standing (7:31) Cougar Town Dancing With the Stars (N) (S) (Live) (9:01) Private Practice Erica’s medical News (N) (CC) (10:35) Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live “Dancing With the WSIL night (N) (CC) (N) (CC) (N) (CC) (CC) condition gets worse. (N) (CC) (N) (CC) Stars”; Ashanti. (N) (CC) $ $ Channel 4 News at Channel 4 News at The Biggest Loser The contestants re- The Voice “Live Eliminations” Vocalists Fashion Star “Out of the Box” The design- Channel 4 News at (10:35) The Tonight Show With Jay (11:37) Late Night WSMV 6pm (N) (CC) 6:30pm (N) (CC) view their progress. (N) (CC) face elimination. (N) (S) (Live) (CC) ers push creative boundaries. (N) 10pm (N) (CC) Leno (CC) With Jimmy Fallon % % Newschannel 5 at 6PM (N) (CC) NCIS “Rekindled” The team investigates a NCIS: Los Angeles “Lone Wolf” A discov- Unforgettable “Trajectories” A second NewsChannel 5 at (10:35) Late Show With David Letter- Late Late Show/ WTVF warehouse fire. -

Redalyc.Youth, Drug Traffic and Hypermasculinity in Rio De Janeiro

VIBRANT - Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology E-ISSN: 1809-4341 [email protected] Associação Brasileira de Antropologia Brasil Zaluar, Alba Youth, drug traffic and hypermasculinity in Rio de Janeiro VIBRANT - Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology, vol. 7, núm. 2, diciembre, 2010, pp. 7- 27 Associação Brasileira de Antropologia Brasília, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=406941910001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Youth, drug traffic and hyper- masculinity in Rio de Janeiro Alba Zaluar Introduction I began my ethnographic studies of violence in the city of Rio de Janeiro al- most by chance when I went to Cidade de Deus, a low-income housing estate project built in the 1960s for those forcibly evicted from the shantytowns. My intention in 1980 was to study voluntary associations, which were typical of the long existing shantytowns, to see what had changed for the dwellers rein- stalled in the new housing project. One major change I found was a new kind of organization of which there had been no record in the literature on pov- erty prior to 1980: drug dealing gangs engaged in incipient turf wars. Since then, I have not been able to stop studying the subject and willy-nilly became an “expert” on it. I undertook two major ethnographic research projects in Cidade de Deus; one by myself and the second with four research assistants, three of them male and one female. -

A Road Map to Academic Success

SPOTLIGHT: YEAR IN REVIEW Suite Escape A look back at the top business Find out which news a ecting New Jersey N.J. executive’s throughout 2011. all-time favorite gift . Page 15 was a pair of silk ® stockings. Page 10 DECEMBER 19, 2011 www.njbiz.com $2.00 A. Gabriel Esteban was inaugurated as the 20th INSIDE Christina Mazza president of Seton Hall University, in October. Boost to development EDA approves tax credits for Jersey City, Long Branch projects. .Page 2 Charitable giving Foundations strive to keep pace with growing needs of the state’s nonpro ts. Page 5 Fueling city growth Bills aim to provide funding to UEZs, but with limits. .Page 5 A road map to academic success New Seton Hall president prioritizes future planning Esteban was inaugurated as of the school’s board of regents, the 156-year-old Catholic univer- said Esteban’s quiet confi dence BY JARED KALTWASSER help but think of ways to im- sity’s 20th president in October. and focused leadership style as Made in USA A. GABRIEL ESTEBAN always prove future ceremonies. He came to the school as provost provost was impressive. Family-owned manufacturer expands aims for the top grade. Even re- “That’s the thing,” he said. in 2007 before being named in- “During that time he began by being true to its roots. Page 10 counting Seton Hall University’s “I start to think ahead. As you’re terim president in July 2010, to put in place some of the key as- Opinion second-annual tree-lighting cer- waiting to get on with the show, upon the retirement of Monsi- pects of improving the academic ■ Editorial: Legislature must reduce emony earlier this month, the you start to think about, ‘How can gnor Robert Sheeran. -

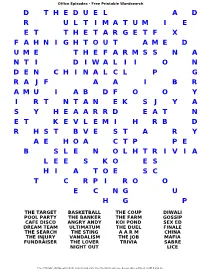

D T H E D U E L a D R U L T I M a T U M I E E T T H E T a R G E T F X F a H N I G H T O U T a M E D U M E T H E F a R M S S

Office Episodes - Free Printable Wordsearch DTHEDUEL AD RULTIMAT UMIE ETTHETARGE TFX FAHNIGHTOUT AMED UMETHEFAR MSSNA NTIDIWAL IION DENCHINALCL PG RAJFA AIBR AMUIABDF OOY IRTNTANEK SJYA SYHEAARRD EATN ETKEVLEMI HRBD RHSTBVES TARY AEHOACTP PE BSLENOL HTRIVIA LEESKO ES HIATOE SC TCRPIR OO ECNG U HGP THE TARGET BASKETBALL THE COUP DIWALI POOL PARTY THE BANKER THE FARM GOSSIP CAFE DISCO ANGRY ANDY KOI POND SEX ED DREAM TEAM ULTIMATUM THE DUEL FINALE THE SEARCH THE STING AARM CHINA THE INJURY VANDALISM THE JOB MAFIA FUNDRAISER THE LOVER TRIVIA SABRE NIGHT OUT LICE Free Printable Wordsearch from LogicLovely.com. Use freely for any use, please give a link or credit if you do. Office Episodes - Free Printable Wordsearch INITIATIONJ URYDUTY T TREC RIMEAID HHIR TCB OAECSGH SNOMR TFTECLREPE UNOO BGSHIHUCOPN ENKN OEIAEBUA OOSWEEE JHTRSCM RKTEGYW LTKWYLLPP EILUTL OCTUFI EDSIYAE OCTHPTRET MNSOA CEAWAHHANM GBD GTLOLFEMT UERS PHARLC FEHRA REDKOOI TTDW POF BWMGOFE DMI UEHRBR AOR SEUTY SETN FRAME TOBY NEW LEADS THE BOAT WORK BUS GETTYSBURG JURY DUTY THE FIRE JOB FAIR INITIATION THE CHUMP TURF WAR SPOOKED THE SECRET WUPHF COM NEW GUYS PROMOS COUNSELING THE FIGHT HOT GIRL MURDER THE CARPET CRIME AID LOCAL AD MONEY THE CLIENT COCKTAILS NEPOTISM BROKE HALLOWEEN PDA Free Printable Wordsearch from LogicLovely.com. Use freely for any use, please give a link or credit if you do. Office Episodes - Free Printable Wordsearch D ENEPOTISM TKNEWGUYS BOUPPTHE JOB ORIRDSEXED TPSOF ATDIWALI HSSKW TH EOAEA HES FGKOIPONDRE LFA AV WDIIB RIHOTGIRLOU CDRR MRAARMTRE EAREE TCMAFIAHKL LIDT FHPMONEYEBA ARA IIRCU CFUO NNOOSOBM B AAMULOE LOPJH EST THE COUP NEW GUYS SPOOKED MURDER THE FARM HOT GIRL TRIVIA CHINA KOI POND LOCAL AD DIWALI MAFIA THE DUEL NEPOTISM GOSSIP SABRE THE BOAT WORK BUS SEX ED MONEY THE FIRE JOB FAIR FINALE BROKE TURF WAR AARM PROMOS LICE THE JOB PDA Free Printable Wordsearch from LogicLovely.com. -

Volume 20: Spring 2017

UNIVERSITY OF DENVER SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL VOLUME XX – EDITORIAL BOARD – JOHN GRONKA EDITOR-IN-CHIEF DREW HOFFMAN ERIN STUTZ SENIOR ARTICLES EDITOR SHANE THOMAS-LOVRIC MANAGING EDITORS SAMIT BHALALA CANDIDACY EDITOR STAFF EDITORS CALLIE BORGMAN COURTNEY DIGUARDI MARISSA NARDE ERIC PANOUSHEK BRETT ROBINSON WILLIAM TAYLOR NATALIE WILLIS FACULTY ADVISOR STACEY BOWERS UNIVERSITY OF DENVER SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLES WHEN IS A RIGHT OF PUBLICITY LICENSE GRANTED TO A LOAN-OUT CORPORATION A FRAUDULENT CONVEYANCE? ............................................................................1 DAVID J. COOK THE “TURF WAR”: GENDER DISCRIMINATION AND THE CREATION OF A HOSTILE WORK ENVIRONMENT THROUGH SYNTHETIC TURF..................................................23 NICOLE PRICE VARYING VERNACULARS: HOW TO FIX THE LANHAM ACT’S WEAKNESS EXPOSED BY THE WASHINGTON REDSKINS ........................................................45 DUSTIN OSBORNE EDITOR’S NOTE The Sports and Entertainment Law Journal is proud to complete its eleventh year of publication. Over the past decade, the Journal has strived to contribute to the academic discourse surrounding legal issues in the sports and entertainment industry by publishing scholarly articles. Volume XX has three featured articles discussing issues and proposing solutions for hot topics we face in the sports and entertainment industry. The first article, written by David Cook, discusses whether or not a creditor can directly reach an artist’s income that is distributed by a studio or other obligor. Moving into a discussion on the differences seen between male and female athletics, Nicole Price explores the disparity in playing surfaces that soccer players face in different competitions. The third and final article, written by Dustin Osborne, considers the extremely controversial Washington Redskin’s name and the ensuing Trademark cancellation We are truly pleased with Volume XX’s publication and would like to the thank the authors for all of their hard work.