Amicus Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Department of Justice U.S. Attorney, District of New Jersey 401 Market Street, Fourth Floor Camden, New Jersey 08101

NEWS United States Department of Justice U.S. Attorney, District of New Jersey 401 Market Street, Fourth Floor Camden, New Jersey 08101 Paul J. Fishman, U.S. Attorney More Information? Contact the Assistant U.S. Attorney or other contact listed below to see if more information is available. News on the Internet: News Releases, related documents and advisories are posted short-term at our website, along with links to our archived releases at the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. Go to: http://www.usdoj.gov/usao/nj/press/ Assistant U.S. Attorneys parry0319.rel KEVIN T. SMITH FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MATTHEW J. SKAHILL Mar. 19, 2010 SUSAN KASE 856-757-5026 Former Camden Police Officer Pleads Guilty to Conspiracy to Deprive Others of Their Civil Rights (More) Public Affairs Office 973-645-2888 Breaking News (NJ) http://www.usdoj.gov/usao/nj/press/ CAMDEN – A former Camden, New Jersey police officer pled guilty today to his role in a conspiracy with other Camden Police officers to deprive others of their civil rights, U.S. Attorney Paul J. Fishman announced. Kevin Parry, 29, admitted before U.S. District Judge Robert B. Kugler that from May 2007 until October 2009, while on duty as a uniformed police officer with the Camden Police Department, he engaged in a conspiracy with at least four other Camden Police officers to deprive persons in New Jersey of the free exercise and enjoyment of rights, privileges and immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States. The other officers were not identified by name. -

Prosecutor Turf War Overshadows $150M Maxim Deal

Portfolio Media. Inc. | 860 Broadway, 6th Floor | New York, NY 10003 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] Prosecutor Turf War Overshadows $150M Maxim Deal By Hilary Russ Law360, New York (September 14, 2011, 4:43 PM ET) -- Maxim Healthcare Services Inc.'s Monday settlement of billing fraud allegations may be remembered for something other than its $150 million price tag, after a rare public turf war erupted following accusations by federal prosecutors that state prosecutors had lied about their role in the case. “It is extraordinary,” said Daniel C. Richman, a professor at Columbia Law School. “The normal way a turf war plays out is through dueling leak programs. It is rare for an office to go on the record.” Maxim's settlement calls for the home health service provider to pay a $20 million criminal penalty and $130 million to settle a whistleblower suit accusing the company of engaging in a decadelong, nationwide billing scheme that allegedly defrauded Medicaid and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs programs. Of that amount, the federal government will get about $70 million and 42 states will split the remaining $60 million. But while divvying up the money isn't a problem, assigning credit appears to be a different story, with New Jersey Attorney General Paula Dow and U.S. Attorney for New Jersey Paul Fishman unleashing a war of words Monday few legal observers have ever seen. Despite a five-year federal criminal probe sparked by a 2004 qui tam suit, prosecutors had largely been able to keep the Maxim investigation and case under wraps. -

National Association of Women Judges Counterbalance Spring 2012 Volume 31 Issue 3

national association of women judges counterbalance Spring 2012 Volume 31 Issue 3 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Poverty’s Impact on the Administration of Justice / 1 President’s Message / 2 Executive Director’s Message / 3 Cambridge 2012 Midyear Meeting and Leadership Conference / 6 MEET ME IN MIAMI: NAWJ 2012 Annual Conference / 8 District News / 10 Immigration Programs News / 20 Membership Moments / 20 Women in Prison Report / 21 Louisiana Women in Prison / 21 Maryland Women in Prison / 23 NAWJ District 14 Director Judge Diana Becton and Contra Costa County native Christopher Darden with local high school youth New York Women in Prison / 24 participants in their November, 2011 Color of Justice program. Read more on their program in District 14 News. Learn about Color of Justice in creator Judge Brenda Loftin’s account on page 33. Educating the Courts and Others About Sexual Violence in Unexpected Areas / 28 NAWJ Judicial Selection Committee Supports Gender Equity in Selection of Judges / 29 POVERTY’S IMPACT ON THE ADMINISTRATION Newark Conference Perspective / 30 OF JUSTICE 1 Ten Years of the Color of Justice / 33 By the Honorable Anna Blackburne-Rigsby and Ashley Thomas Jeffrey Groton Remembered / 34 “The opposite of poverty is justice.”2 These words have stayed with me since I first heard them Program Spotlight: MentorJet / 35 during journalist Bill Moyers’ interview with civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson. In observance News from the ABA: Addressing Language of the anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, they were discussing what Dr. Access / 38 King would think of the United States today in the fight against inequality and injustice. -

A Road Map to Academic Success

SPOTLIGHT: YEAR IN REVIEW Suite Escape A look back at the top business Find out which news a ecting New Jersey N.J. executive’s throughout 2011. all-time favorite gift . Page 15 was a pair of silk ® stockings. Page 10 DECEMBER 19, 2011 www.njbiz.com $2.00 A. Gabriel Esteban was inaugurated as the 20th INSIDE Christina Mazza president of Seton Hall University, in October. Boost to development EDA approves tax credits for Jersey City, Long Branch projects. .Page 2 Charitable giving Foundations strive to keep pace with growing needs of the state’s nonpro ts. Page 5 Fueling city growth Bills aim to provide funding to UEZs, but with limits. .Page 5 A road map to academic success New Seton Hall president prioritizes future planning Esteban was inaugurated as of the school’s board of regents, the 156-year-old Catholic univer- said Esteban’s quiet confi dence BY JARED KALTWASSER help but think of ways to im- sity’s 20th president in October. and focused leadership style as Made in USA A. GABRIEL ESTEBAN always prove future ceremonies. He came to the school as provost provost was impressive. Family-owned manufacturer expands aims for the top grade. Even re- “That’s the thing,” he said. in 2007 before being named in- “During that time he began by being true to its roots. Page 10 counting Seton Hall University’s “I start to think ahead. As you’re terim president in July 2010, to put in place some of the key as- Opinion second-annual tree-lighting cer- waiting to get on with the show, upon the retirement of Monsi- pects of improving the academic ■ Editorial: Legislature must reduce emony earlier this month, the you start to think about, ‘How can gnor Robert Sheeran. -

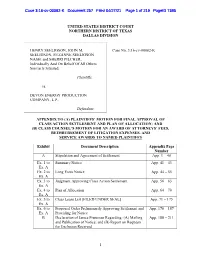

Appendix to Plaintiffs' Motion for Final Approval of Settlement, Plan of Allocation, and Attorneys' Fees

Case 3:16-cv-00082-K Document 257 Filed 04/27/21 Page 1 of 219 PageID 7385 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION HENRY SEELIGSON, JOHN M. Case No. 3:16-cv-00082-K SEELIGSON, SUZANNE SEELIGSON NASH, and SHERRI PILCHER, Individually And On Behalf Of All Others Similarly Situated, Plaintiffs, vs. DEVON ENERGY PRODUCTION COMPANY, L.P., Defendant. APPENDIX TO (A) PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT AND PLAN OF ALLOCATION; AND (B) CLASS COUNSEL’S MOTION FOR AN AWARD OF ATTORNEYS’ FEES, REIMBURSEMENT OF LITIGATION EXPENSES, AND SERVICE AWARDS TO NAMED PLAINTIFFS Exhibit Document Description Appendix Page Number A Stipulation and Agreement of Settlement App. 1 – 40 Ex. 1 to Summary Notice App. 41 – 43 Ex. A Ex. 2 to Long Form Notice App. 44 – 55 Ex. A Ex. 3 to Judgment Approving Class Action Settlement App. 56 – 63 Ex. A Ex. 4 to Plan of Allocation App. 64 – 70 Ex. A Ex. 5 to Class Lease List [FILED UNDER SEAL] App. 71 – 175 Ex. A Ex. 6 to Proposed Order Preliminarily Approving Settlement and App. 176 – 187 Ex. A Providing for Notice B Declaration of James Prutsman Regarding: (A) Mailing App. 188 – 211 and Publication of Notice; and (B) Report on Requests for Exclusion Received 1 Case 3:16-cv-00082-K Document 257 Filed 04/27/21 Page 2 of 219 PageID 7386 C Declaration of Joseph H. Meltzer in Support of Class App. 212 – 265 Counsel’s Motion for An Award of Attorneys’ Fees Filed on Behalf of Kessler Topaz Meltzer & Check LLP D Declaration of Brad Seidel in Support of Class App. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT of NEW JERSEY : FREDERICK CARLTON “CARL” : LEWIS, : : Civil Action No. Plaintiff, : 11

Case 1:11-cv-02381-NLH -AMD Document 88 Filed 09/06/11 Page 1 of 34 PageID: 1864 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY : FREDERICK CARLTON “CARL” : LEWIS, : : Civil Action No. Plaintiff, : 11-cv-2381 (NLH)(AMD) : v. : OPINION : SECRETARY OF STATE KIM : GUADAGNO, et al., : : Defendants. : : APPEARANCES: William M. Tambussi, Esquire John E. Wallace, Jr., Esquire William F. Cook, Esquire Christopher A. Orlando, Esquire and Michael Joseph Miles, Esquire Brown & Connery L.L.P. 360 Haddon Avenue Westmont, N.J. 08108 Attorneys for Plaintiff Frederick Carlton Lewis Donna Kelly, Esquire and Robert T. Lougy, Esquire Division of Law & Public Safety Office of Attorney General of New Jersey Richard J. Hughes Justice Complex 25 Main Street P.O. Box 112 Trenton, N.J. 08625 Attorneys for Defendants Kim Guadagno and Paula Dow Howard Lane Goldberg, Esquire and Sherri L. Schweitzer, Esquire Office of Camden County Counsel 520 Market Street Courthouse, 14th Floor Camden, N.J. 08102 Case 1:11-cv-02381-NLH -AMD Document 88 Filed 09/06/11 Page 2 of 34 PageID: 1865 Attorneys for Defendant Joseph Ripa James T. Dugan, Esquire Atlantic County Department of Law 1333 Atlantic Avenue 8th Floor Atlantic City, N.J. 08401 Attorney for Defendant Edward P. McGettigan Mark D. Sheridan, Esquire and Mark C. Errico, Esquire Drinker Biddle & Reath, L.L.P. 500 Campus Drive Florham Park, N.J. 07932 Attorneys for Intervenors-Defendants William Layton and Ted Costa HILLMAN, District Judge Plaintiff, Frederick Carlton “Carl” Lewis, has brought suit against Defendants, New Jersey Secretary of State Kim Guadagno, New Jersey Attorney General Paula Dow, Camden County Clerk Joseph Ripa, Burlington County Clerk Timothy Tyler, and Atlantic County Clerk Edward P. -

Ensuring Accountability and Oversight in Tolling

S. HRG. 112–762 PROTECTING COMMUTERS: ENSURING ACCOUNTABILITY AND OVERSIGHT IN TOLLING HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON SURFACE TRANSPORTATION AND MERCHANT MARINE INFRASTRUCTURE, SAFETY, AND SECURITY OF THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 18, 2012 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 80–594 PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 11:32 Apr 30, 2013 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\80594.TXT JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas, Ranking JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine BARBARA BOXER, California JIM DEMINT, South Carolina BILL NELSON, Florida JOHN THUNE, South Dakota MARIA CANTWELL, Washington ROGER F. WICKER, Mississippi FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia MARK PRYOR, Arkansas ROY BLUNT, Missouri CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri JOHN BOOZMAN, Arkansas AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota PATRICK J. TOOMEY, Pennsylvania TOM UDALL, New Mexico MARCO RUBIO, Florida MARK WARNER, Virginia KELLY AYOTTE, New Hampshire MARK BEGICH, Alaska DEAN HELLER, Nevada ELLEN L. DONESKI, Staff Director JAMES REID, Deputy Staff Director JOHN WILLIAMS, General Counsel RICHARD M. RUSSELL, Republican Staff Director DAVID QUINALTY, Republican Deputy Staff Director REBECCA SEIDEL, Republican General Counsel and Chief Investigator SUBCOMMITTEE ON SURFACE TRANSPORTATION AND MERCHANT MARINE INFRASTRUCTURE, SAFETY, AND SECURITY FRANK R. -

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

No. 13-_________ ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- JOHN M. DRAKE, GREGORY C. GALLAHER, LENNY S. SALERNO, FINLEY FENTON, SECOND AMENDMENT FOUNDATION, INC., AND ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY RIFLE & PISTOL CLUBS, INC., Petitioners, v. EDWARD A. JEREJIAN, THOMAS D. MANAHAN, JOSEPH R. FUENTES, ROBERT JONES, RICHARD COOK, AND JOHN JAY HOFFMAN, Respondents. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Third Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI --------------------------------- --------------------------------- DAVID D. JENSEN ALAN GURA DAVID JENSEN PLLC Counsel of Record 111 John Street, Suite 420 GURA & POSSESSKY, PLLC New York, New York 10038 105 Oronoco Street, 212.380.6615 Suite 305 [email protected] Alexandria, Virginia 22314 703.835.9085 [email protected] ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i QUESTIONS PRESENTED The Second Amendment “guarantee[s] the indi- vidual right to possess and carry weapons in case of confrontation.” District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 592 (2008). But in accordance with “the overriding philosophy of [New Jersey’s] Legislature . to limit the use of guns as much as possible,” State v. Valentine, 124 N.J. Super. 425, 427, 307 A.2d 617, 619 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 1973), New Jersey law bars all but a small handful of individuals show- ing “justifiable need” from carrying a handgun for self-defense, N.J. Stat. Ann. § 2C:58-4(c). The federal appellate courts, and state courts of last resort, are split on the question of whether the Second Amendment secures a right to carry handguns outside the home for self-defense. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of ILLINOIS in RE BAXTER INTERNATIONAL INC. SECURITIES LITIGATION Case No. 1:19-C

Case: 1:19-cv-07786 Document #: 66 Filed: 07/06/21 Page 1 of 51 PageID #:1934 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS Case No. 1:19-cv-07786 IN RE BAXTER INTERNATIONAL INC. District Judge Sara L. Ellis SECURITIES LITIGATION Magistrate Judge Jeffrey I. Cummings JOINT DECLARATION OF JAMES A. HARROD AND SHARAN NIRMUL IN SUPPORT OF (I) LEAD PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF SETTLEMENT AND PLAN OF ALLOCATION AND (II) LEAD COUNSEL’S MOTION FOR ATTORNEYS’ FEES AND LITIGATION EXPENSES Case: 1:19-cv-07786 Document #: 66 Filed: 07/06/21 Page 2 of 51 PageID #:1935 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY OF TERMS .............................................................................................................. iii I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 II. PROSECUTION OF THE ACTION .................................................................................. 6 A. Background ................................................................................................................ 6 B. Appointment of Lead Plaintiffs and Lead Counsel.................................................... 8 C. Lead Plaintiffs’ Investigation and Preparation and Filing of the Complaint ............. 8 D. Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss the Complaint, the Court’s MTD Order, and Lead Plaintiffs’ Preparation of a Second Amended Complaint .......................... 9 III. MEDIATION AND SETTLEMENT .............................................................................. -

The New Jersey Legislative Select Committee on Investigation's

You Are Viewing an Archived Report from the New Jersey State Library Minority Statement: The New Jersey Legislative Select Committee on Investigation’s George Washington Bridge Inquiry December 8, 2014 You Are Viewing an Archived Report from the New Jersey State Library Table of Contents Introduction Page 2 I: The Public Committee Started Down a Political Road Page 5 1. Democrats’ Politics Trumped Public Trust Page 7 2. ‘The Greater the Power, the More Dangerous the Abuse’ Page 9 3. Top Members Should’ve Been Banned from Committee Page 12 4. A Member Proactively Addressed Perceived Issues Page 22 II: A Questionable Choice for ‘Bipartisan’ Inquiry Page 25 1. A Go-To Firm for Democrats: Jenner & Block Page 27 2. Additional Problems with Committee Counsel Page 33 III: Co-Chairs Sabotaged the Inquiry Page 38 1. Prejudicial Comments: A Hunt for Attention Page 39 a. ‘Inquiry to Lynching’ Page 45 b. Co-Chairwoman: ‘The governor has to be responsible’ Page 49 c. Co-Chairs Should’ve Quit Committee, Too Page 62 d. Co-Chairs Did What They Criticized Mastro For Doing Page 63 e. Co-Chairs Continued to Advance Democrat Scheme Page 67 2. Unlawfully Leaked Documents? Page 72 IV: Inquiry’s Doom: Bungled Court Case Page 83 V: Republicans Tried to Develop a Successful Inquiry Page 87 1. Committee Should’ve Been Democratized Page 88 2. Painfully Wasteful Meetings Could’ve Been Avoided Page 90 VI: A High Price for Failure Page 98 1. Administration’s Transparency Opened Door for Reform Page 99 2. Democrats Shut the Door on Reform Page 103 3. -

Dir-2011-1-Evidenceretention.Pdf

CHRIS CHRISTIE State of New Jersey PAULA T. Dow Governor OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL Attorney General DEPARTMENT OF LAW AND PUBLIC SAFETY KIM GUADAGNO DWISION OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE STEPHEN J. TAYLOR PO Box 085 Lieutenant Governor TRENTON, NJ 08625-0085 Director TELEPHONE: (609) 984-6500 DIRECTIVE NO. 2011 - 1 REVISES AND REPLACES DIRECTIVE 20101 - TO: DIRECTOR, DIVISION OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE ALL COUNTY PROSECUTORS ALL POLICE CHIEFS ALL LAW ENFORCEMENT CHIEF EXECUTIVES FROM: PAULA T. DOW, ATTORNEY GENERAL DATE: January 6, 2011 SUBJECT: ATTORNEY GENERAL GUIDELINES FOR THE RETENTION OF EVIDENCE On March 9, 2010, I issued Law Enforcement Directive 2010-1, promulgating Guidelines for the Retention of Evidence. During the first year of the implementation of this program, questions have arisen concerning sections of the guidelines that require clarification. Therefore, I am reissuing the directive and guidelines, with necessary amendments to address the questions that have arisen regarding the original guidelines. This Directive and the Attached Guidelines supersede and replace Law Enforcement Directive 2010-1. The primary duty of the Prosecutor is not to convict, but to ensure that justice is done. State v. Ramseur, 106 N.J. 123 (1987); State v. Zola, 112 N.J. 384 (1988). In keeping with this trust, the Attorney General and the County Prosecutors hereby intend to provide for the retention of evidence in criminal cases to protect public safety and the interests of crime victims and their families, and to afford to those who are serving a sentence for a crime the opportunity to challenge their convictions, in appropriate cases. The attached Attorney General Guidelines for the Retention of Evidence in criminal cases have been jointly formulated by the Attorney General and the County Prosecutors and are promulgated pursuant to the Criminal Justice Act of 1970, N.J.S.A. -

BOE Extends Fyffe Contract; Queen Latifah Films Perfect

Happy New Year 2007 Ad Populos, Non Aditus, Pervenimus Published Every Thursday Since September 3, 1890 (908) 232-4407 USPS 680020 Thursday, December 28, 2006 OUR 116th YEAR – ISSUE NO. 52-2006 Periodical – Postage Paid at Westfield, N.J. www.goleader.com [email protected] SIXTY CENTS Greg Ryan, Nordette N. Adams, Mike Smith, Betsey Burgdorf and Horace Corbin for The Westifeld Leader CREATIVE COSTUMING (November 2)…Madelin Jackson, 20 months old, was Mott’s apple juice at this year’s Halloween parade in downtown Westfield. Ciara Rodger, 7, was a box of French fries and won second place in her age category; FREE AT LAST (September 21)...Fred, left, and Michael Chemidlin attend a Fanwood-Scotch Plains Rotary Club luncheon. Michael spoke to Rotarians and guests about his two-month imprisonment in Sierra Leone earlier this year; LET THERE BE LIGHT (September 7)...As seen from above in the office at the Rialto Theatre, workers ready the new traffic light in Westfield at the convergence of East Broad Street, Mountain Avenue and Central Avenue; STAR STRUCK (August 17)...Claudia Romeo, a Wilson Elementary School student, met Queen Latifah while she was in town filming Perfect Christmas; THE POLE STAYS (July 20)…The landmark barber pole of former Jerry’s Barber Shop on Broad Street in Westfield was given a reprieve to stay in the downtown as the Planning board approved the expansion of Jersey Mike’s at that location and the owner agreed to maintain the landmark. BOE Extends Fyffe Contract; Queen Latifah Films Perfect Christmas Downtown; FMBA Reaches 5-Year Contract; Kean Loses Election Bid JULY tract, retroactive to July 1, 2005.