From Narrative to Database in the Remakes of Space Battleship Yamato and Mobile Suit Gundam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anime Expo Lite 2021 Sweepstakes Official Rules

ANIME EXPO LITE 2021 SWEEPSTAKES OFFICIAL RULES 1. Official Rules. The Anime Expo Lite 2021 Sweepstakes (the “Promotion”) is subject to these Official Rules, except as expressly stated otherwise. No purchase necessary. A purchase does not improve your chances of winning. Void where prohibited. The Sweepstakes is sponsored by Society for the Promotion of Japanese Animation, 1522 Brookhollow Dr. Suite 1, Santa Ana, CA 92705 (the “Sponsor”). 2. Eligibility. The Sweepstakes is open to legal residents of the United States (but excluding U.S. military installations in foreign countries and all other U.S. territories and possessions), who are 18 years of age or older at the start of the Promotion (“Entrant”). By participating in the Sweepstakes, Entrant agrees to be fully and unconditionally bound by these Official Rules and the decisions of Sponsor. 3. Privacy. The information you provide in your entry will be used for administering this Promotion and for marketing purposes in accordance with Sponsor’s privacy policy found here: http://www.anime-expo.org/plan/policies/. 4. Sweepstakes Period. The Sweepstakes begins at 12:00 p.m PDT on June 25, 2021 and ends at 12:00 p.m. PDT on July 16, 2021 (the "Promotion Period"). 1. How to Enter the Sweepstakes. During the Sweepstakes Period, you can enter the Sweepstakes through the following methods: a. Purchase: You may purchase an online pass for Anime Expo Lite 2021 from https://www.tixr.com/groups/animeexpolite/events/anime-expo-lite-2021- benefitting-hate-is-a-virus-23015 (“Website”); Note: All online passes purchased prior to the Sweepstakes Period are also eligible to enter. -

Event Highlights

Event Highlights Events • Yoshihiro Ike: Anime Soundtrack World sponsored by Studio Kitchen: International debut performance of one of Japan’s most prolific music composers in the industry featuring a 50 piece orchestra that will bring to life the greatest collection of soundtracks from Tiger & Bunny, Saint Seiya, B: The Beginning, Dororo, Rage of Bahamut:Genesis, and Shadowverse. • 4DX Anime Film Festival: Featuring Detective Conan: Zero The Enforcer, Mobile Suit Gundam NT (Narrative) and Mobile Suit Gundam 00 the MOVIE – A Wakening of the Trailblazer- enhanced with immersive, multi-sensory 4DX motion and environmental effects. • Anime Expo Masquerade & World Cosplay Summit US Finals • Inside the World of Street Fighter & Street Fighter V: Arcade Edition - Ultimate Cosplay Showdown sponsored by Capcom • LOVE LIVE! SUNSHINE!! Aqours World LoveLive! in LA ~BRAND NEW WAVE~ • Fate/Grand Order USA Tour • Fashion Show: Featuring Japanese brands h. NAOTO with designer Hirooka Naoto, Acryl CANDY with guest model Haruka Kurebayashi, amnesiA¶mnesiA with guest model Yo from Matenrou Opera, and Metamorphose with designer Chinatsu Taira. In addition, Hot Topic will reveal a new collection and HYPLAND will debut new items from their BLEACH collaboration. Programming • 15+ Premieres & Exclusive Screenings: Promare, Dr. Stone, In/Spectre, Human Lost, Fire Force, My Hero Academia Season 4, “Pokémon: Mewtwo Strikes Back—Evolution!” and more. • 900+ Hours of Panels, Events, Screenings, Workshops, and more. • Programming Tracks: Career, Culture, Family, and Academic Program. • Pre-Show Night on July 4 (6 - 10pm) 150+ Guests & Industry Appearances • Creators: Katsuhiro Otomo, Bisco Hatori, Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, Yusuke Kozaki, Atsushi Ohkubo, Utako Yukihiro. • Japanese Voice Actors: Rica Matsumoto, Mamoru Miyano, Maya Uchida, Kaori Nazuka. -

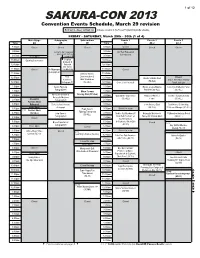

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

The Formation of Temporary Communities in Anime Fandom: a Story of Bottom-Up Globalization ______

THE FORMATION OF TEMPORARY COMMUNITIES IN ANIME FANDOM: A STORY OF BOTTOM-UP GLOBALIZATION ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Geography ____________________________________ By Cynthia R. Davis Thesis Committee Approval: Mark Drayse, Department of Geography & the Environment, Chair Jonathan Taylor, Department of Geography & the Environment Zia Salim, Department of Geography & the Environment Summer, 2017 ABSTRACT Japanese animation, commonly referred to as anime, has earned a strong foothold in the American entertainment industry over the last few decades. Anime is known by many to be a more mature option for animation fans since Western animation has typically been sanitized to be “kid-friendly.” This thesis explores how this came to be, by exploring the following questions: (1) What were the differences in the development and perception of the animation industries in Japan and the United States? (2) Why/how did people in the United States take such interest in anime? (3) What is the role of anime conventions within the anime fandom community, both historically and in the present? These questions were answered with a mix of historical research, mapping, and interviews that were conducted in 2015 at Anime Expo, North America’s largest anime convention. This thesis concludes that anime would not have succeeded as it has in the United States without the heavy involvement of domestic animation fans. Fans created networks, clubs, and conventions that allowed for the exchange of information on anime, before Japanese companies started to officially release anime titles for distribution in the United States. -

Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST 320Kbpsrar

Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST 320kbpsrar Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST 320kbpsrar 1 / 3 2 / 3 Download FLAC Gundam Seed - Seed Complete Best 2004 lossless CD, MP3, M4A. Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST [320kbps].rar Gundam .... Mobile Suit Gundam SEED is an anime series developed by Sunrise and directed by Mitsuo ... The Archangel arrives in Alaska but ZAFT launches a full-scale attack on the base overpowering their enemies. ... Mobile Suit Gundam SEED ~ SEED DESTINY BEST "THE BRIDGE" Across the Songs from GUNDAM SEED .... Jump to Mobile Suit Gundam SEED Complete Best - Mobile Suit Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST. Compilation album by. T.M.Revolution, See- Saw, .... View credits, reviews, tracks and shop for the 2004 CD release of Mobile Suit Gundam Seed Complete Best on Discogs.. Jump to Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST 320kbpsrar - tercardmitrue - All Gundam Seed + Destiny Opening ... Best* Title: Gundam 00 Complete Best Type OST: .... Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST [320kbps].rar ... http://www.mediafire.com/file/796jpbeqq39ny68/amd-hh full moon paper & qp.zip.. Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST [320kbps].rar DOWNLOAD. 5f91d47415 Music of Mobile Suit Gundam SEED - WikipediaMusic of Mobile .... This cd has all the songs from the anime and is very enjoyable. The songs are longer than the anime openings, but are still very enjoyable and fun to listen to.. Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST [320kbps].rar >> http://urllio.com/rwc1z 89e59902e3.. Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST [320kbps].rarhttp://bltlly.com/11tes0.. Album: Mobile Suit Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST (機動戦士ガンダムSEED COMPLETE BEST); Released: 2003.09.26; Catalog Number: AICL-1489~90 ... 54ea0fc042 Windows Vista Crack Product 21 Mettle Freeform Pro Mac Crack 20 Diamond Necklace Full Movie Free Download gilad hekselman transcription pdf download Falkovideo 86 kenneth laudon sistemas de informacion gerencial pdf download Hassan Sadiq Qasida Mp4 Free Download Skold Skold Rar conant gardens maschine serial 14 Hindi Medium 2 full movie download in 720p hd 3 / 3 Gundam SEED COMPLETE BEST 320kbpsrar. -

Japanese Animation Guide: the History of Robot Anime

Commissioned by Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs Manga, Animation, Games, and Media Art Information Bureau Japanese Animation Guide: The History of Robot Anime Compiled by Mori Building Co., Ltd. 2013 Commissioned by Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs Manga, Animation, Games, and Media Art Information Bureau Japanese Animation Guide: The History of Robot Anime Compiled by Mori Building Co., Ltd. 2013 Addition to the Release of this Report This report on robot anime was prepared based on information available through 2012, and at that time, with the exception of a handful of long-running series (Gundam, Macross, Evangelion, etc.) and some kiddie fare, no original new robot anime shows debuted at all. But as of today that situation has changed, and so I feel the need to add two points to this document. At the start of the anime season in April of 2013, three all-new robot anime series debuted. These were Production I.G.'s “Gargantia on the Verdurous Planet," Sunrise's “Valvrave the Liberator," and Dogakobo and Orange's “Majestic Prince of the Galactic Fleet." Each was broadcast in a late-night timeslot and succeeded in building fanbases. The second new development is the debut of the director Guillermo Del Toro's film “Pacific Rim," which was released in Japan on August 9, 2013. The plot involves humanity using giant robots controlled by human pilots to defend Earth’s cities from gigantic “kaiju.” At the end of the credits, the director dedicates the film to the memory of “monster masters” Ishiro Honda (who oversaw many of the “Godzilla” films) and Ray Harryhausen (who pioneered stop-motion animation techniques.) The film clearly took a great deal of inspiration from Japanese robot anime shows. -

Bandai June New Product

Bandai June New Product ZZ II "Gundam Build Fighters", Bandai HGBF 1/144 Launching alongside the release of a new Gundam Build Fighters Try episode, the popular Z II is now available! Capable of transforming into its Wave Rider form, the model kit also comes with powerful large-scale weaponry. Set includes a large beam rifle, transformation replacement parts, and interchangeable hand. Runner x12. Foil Sticker x1. Instruction manual x1. Approximately 5.5" Tall Package Size: Approximately 12.2"x7.8"x3.1" MSRP: $27.99 Gyancelot "Gundam Build Fighters", Bandai HGBF 1/144 From the Gyan family, comes a new model kit featuring Gyancelot! With expert detailing on the shield and weapons, the color scheme and textures accurately reproduces the look from the anime! The large lance appears in the shape of the crest of the Principality of Zeon, and its blades can be opened or closed through the use of replacement parts. Set includes large lance, beam saber, shield, and interchangeable hands. Runner x11. Foil sticker x1. Instruction manual x1. Approx. 5" Tall Package Size: Approx. 11.7"x7.4"x3.0" MSRP: $19.99 Gya Eastern Weapons "Gundam Build Fighters", Bandai HGBC 1/144 This is a kit focusing on parts for hand-held weapons from the Build Custom series! The parts can be used to customize existing models from various 1/144 series. The large rifle from the HG 1/144 ZZ II can be combined with a newly molded clay bazooka and optional parts for the lance from the Gyancelot can be customized as well. -

Theme Exploration and Authorial Intent in Mobile Suit Gundam

Looking towards the future: Theme exploration and authorial intent in Mobile Suit Gundam Bachelor’s thesis Kim Ilomäki University of Jyväskylä Department of Language and Communication English 5.2020 JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanistis-yhteiskuntatieteellinen tiedekunta Kieli- ja viestintätieteiden laitos Tekijä – Author Kim Ilomäki Työn nimi – Title Looking towards the future: Theme exploration and authorial intent in Mobile Suit Gundam Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level Englannin kieli Kandidaatintutkielma Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages Toukokuu 2020 16 Tiivistelmä – Abstract Mobile Suit Gundam on vuonna 1979 julkaistu TV anime sarja, joka oli omana aikanaan erittäin vaikutusvaltainen ja joka jatkaa olemassaoloaan monissa eri muodoissa. Sarjaa on tutkittu ennenkin mutta tekijä Yoshiyuki Tominon pääteemasta ei ole tehty merkittävää tutkimusta. Tässä tutkimuksessa analysoidaan Yoshiyuki Tominon omin sanoin kuvaavaa teemaa; ’aikuiset ovat vihollisia.’ Sarjan tarina sijoittuu sci-fi tulevaisuuteen, jossa ihmiset ovat rakentaneet siirtokuntia avaruuteen Maan ympärille. Tarinan konflikti kertoo sodasta joka on syttynyt avaruudessa ja Maassa asuvien ihmisten välillä. Tarinan suurin vaikutus omalla ajallaan oli näyttää todenmukaista sodankäyntiä, jossa kumpikaan osapuoli sodassa ei ollut hyvä eikä paha. Tarinan päähenkilöt koostuvat nuorista henkilöistä jotka joutuvat ottamaan osaa sotaan vastoin heidän tahtoaan. Käytän aineistolähtöistä analyysia tuodakseni esiin toistuvia teemoja tarinassa -

Collaborative Creativity, Dark Energy, and Anime's Global Success

Collaborative Creativity, Dark Energy, and Anime’s Global Success ◆特集*招待論文◆ Collaborative Creativity, Dark Energy, and Anime’s Global Success 協調的創造性、ダーク・エナジー、アニメの グローバルな成功 Ian Condry Associate Professor, Comparative Media Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology コンドリー・イアン マサチューセッツ工科大学比較メディア研究准教授 In this essay, I give an overview of some of the main ideas of my new book The Soul of Anime: Collaborative Creativity and Japan’s Media Success Story. Drawing on ethnographic research, including fieldwork at Madhouse, as well as a historical consideration of the original Gundam series, I discuss how anime can be best understood in terms of platforms for collaborative creativity. I argue that the global success of Japanese animation has grown out of a collective social energy that operates across industries—including those that produce film, television, manga (comic books), and toys and other licensed merchandise—and connects fans to the creators of anime. For me, this collective social energy is the soul of anime. 本論文において、拙著『アニメのダーク・エナジー:協調的創造性と日本のメディアの成功例』 における中心的なアイデアの紹介を行う。アニメを制作する企業マッドハウスにおけるフィール ドワークを含む、人類学的な研究を行うとともに、オリジナルの『ガンダム』シリーズに関する 歴史的な考察をふまえて、協調的創造性のプラットフォームとしてアニメを位置付けることがで きるかどうか検討する。日本アニメのグローバルな成功は、映画、テレビ、漫画、玩具、そして その他のライセンス事業を含めて、アニメファンと創作者をつなぐ集団的なソーシャル・エナジー に基づいていると主張する。このような集団的なソーシャル・エナジーがアニメの精神であると 著者は考えている。 Keywords: Media, Popular Culture, Globalization, Japan, Ethnography Acknowledgements: Thank you to Motohiro Tsuchiya for including me in this project. I think “Platform Lab” is an excellent rubric because I believe media should be viewed as a platform of participation rather than content for consumption. I view scholarship the same way. My anime research was supported by the Japan Foundation, the US National Science Foundation, and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. I have also received generous funding from, MIT, Harvard, Yale, and the Fulbright program. -

“Wonder Park Plus” Opens in Hong Kong Causeway Bay, April 19 (Saturday)

Dear all 9th April, 2008 "Gundam Senjyo No Kizuna" first appears in overseas! The new business store crowded with group Synergy appears in Hong Kong. “Wonder Park Plus” opens in Hong Kong Causeway Bay, April 19 (Saturday). Namco Bandai Holdings President: Takeo Takasu Headquarter: Tokyo Minato-ku Namco Limited President: Masahiro Tachibana Headquarter: Tokyo Ota-ku Namco Enterprises Asia Ltd, in charge of the management of amusement facilities in Hong Kong of Namco Bandai Group (Hong Kong President and Representative Director of the headquarter: Mr. Shuhei Ino) opens large-scale amusement facilities "Wonder Park Plus" on April 19 (Saturday), 2008. “Wonder Park Plus” is located on the 6/F in the World Trade Centre, Causeway Bay, the centre of Hong Kong. It expects one million of customers visit in the first year. Namco Wonder Park WTC (World Trade Centre) shop was Image of entrance ©SOTSU・SUNRISE redecorated, including a lot of popular contents of the Namco Bandai Group, and the first compound of amusement facilities in foreign countries. It aims at the base for the transmission of information of entertainment from Japan where group synergy was made an embodiment. It is not only a flagship store of Namco Enterprises Asia Ltd, it goes forward as the origin of sending information in Asian regions of the Namco Bandai Group. ・Lots of amusement machines first appear in overseas such as “Gundam Senjyo No Kizuna” Beginning as the first overseas product by Namco Bandai Games, we have 8 sets of “Gundam Senjyo No Kizuna” which is a dome screen type of strategy team fighting game famous in Japan, Asia version of “Taiko No Tatsujin 11” and Tamagotchi print game machines which enables us to take photo with the Tamagotchi we bring up. -

Hypersphere Anonymous

Hypersphere Anonymous This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ISBN 978-1-329-78152-8 First edition: December 2015 Fourth edition Part 1 Slice of Life Adventures in The Hypersphere 2 The Hypersphere is a big fucking place, kid. Imagine the biggest pile of dung you can take and then double-- no, triple that shit and you s t i l l h a v e n ’ t c o m e c l o s e t o o n e octingentillionth of a Hypersphere cornerstone. Hell, you probably don’t even know what the Hypersphere is, you goddamn fucking idiot kid. I bet you don’t know the first goddamn thing about the Hypersphere. If you were paying attention, you would have gathered that it’s a big fucking 3 place, but one thing I bet you didn’t know about the Hypersphere is that it is filled with fucked up freaks. There are normal people too, but they just aren’t as interesting as the freaks. Are you a freak, kid? Some sort of fucking Hypersphere psycho? What the fuck are you even doing here? Get the fuck out of my face you fucking deviant. So there I was, chilling out in the Hypersphere. I’d spent the vast majority of my life there, in fact. It did contain everything in my observable universe, so it was pretty hard to leave, honestly. At the time, I was stressing the fuck out about a fight I had gotten in earlier. I’d been shooting some hoops when some no-good shithouses had waltzed up to me and tried to make a scene. -

Continuing to Innovate with a Focus on Global Business Initiatives Aligned with Changes in Our Markets

NEWSLETTER September 2018 BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. BANDAI NAMCO Mirai-Kenkyusho 5-37-8 Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-0014 Mitsuaki Taguchi Interview with the President President & Representative Director, BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. Continuing to innovate with a focus on global business initiatives aligned with changes in our markets Under the Mid-term Plan, the Group announced a mid-term vision of CHANGE for the NEXT — Empower, Gain Momentum, and Accelerate Evolution, and launched a five-Unit system. In the first quarter, the Group achieved record-high sales. In these ways, the Mid-term Plan has gotten off to a favorable start. In this issue of the newsletter, BANDAI NAMCO Holdings’ President Mitsuaki Taguchi discusses the future results forecast and the situation with each of the Group’s Units. How were the results in the first What is the outlook for the future? for the mature fan base, BANDAI SPIRITS quarter? Taguchi: In our industry, the environment is CO., LTD., a new company that consolidates Taguchi: In the first quarter of FY2019.3, in undergoing drastic changes, and it is difficult the mature fan base business of the Toys and comparison with the same period of the previous to forecast all of the future trends based on Hobby Unit, started fullscale operation. With year, each business recorded favorable overall three months of results. Considering bolstered a separate organizational structure and a clarified progress with core IP* and products/services, marketing and promotion for businesses mission, the sense of speed in this business despite differences in the home video game recording favorable results; recent business has increased.