University of Warwick Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crash Claims a Life

A3 + PLUS >> Sitel on the way back? Story below LOCAL wSTEM CAMP Last 4 prelim slots ‘Zombie’ germs? filled at the Spirit No prob at FWES See Page 2A See Page 6A TUESDAY, JULY 24, 2018 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Peoples State Bank will merge with Drummond SEE STORY 3A Peoples State Bank in Lake City TONY BRITT/Lake City Reporter Crash ‘Summer of ‘72’ JOBS Sitel on claims the way a life One LC man hits, kills back? another in Suwannee. Call center to start hiring Wednesday. From staff reports TONY BRITT/Lake City Reporter A 26-year-old Lake City By CARL MCKINNEY Members of Traildiver tune their instruments at the Summer of ‘72 Festival on Sat. man was killed Sunday [email protected] morning when he was struck by a a car as he walked on Sitel Lake City appears ready State Road 247 in Suwannee to start hiring again, a little County. Beer, bands, bikinis over a month after the company TalonWHY Chase Richman, BANK 26, WITH PEOPLE’S STATE BANK? announced it was ceasing opera- WHY BANK WITH PEOPLE’S STATE BANK? died at WHYthe scene. BANK WITH PEOPLE’SWHY600-plus BANK attendSTATE WITH BANK?place PEOPLE’S Friday evening STATE and Company BANK? of Gainesville, tions at the call center. The vehicle’sWHY driver, BANK John WITH PEOPLE’Sinaugural event. STATE BANK?most of Saturday after- which sponsored the event The telecommunications firm, Frederick Benz, 50, of Lake noon at Rum 138, included with Rum 138, the art which provides outsourced cus- City, was taken to the hospital WHY BANK WITH PEOPLE’Scamping, live music, STATE art, a BANK?gallery/canoe and kayak tomer support, IT and other ser- with non life-threateningWHY BANK inju- WITHBy PEOPLE’STONY BRITT STATEsilent BANK? disco, 25 area bands outpost. -

MELBOURNE PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 03Rd June 2012

http://prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Repo... MELBOURNE PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 03rd June 2012 06:00 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hip for kids? Join the team for the latest in gaming, sport, pop culture, movies, music and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 06:05 am Beyblade Metal Fusion (Rpt) CC G A new cast of Beyblade characters continue the constant battle between good and evil! Gingka and his group of loyal friends must defeat the Dark Nebula before they unleash their fury on the world! 06:30 am Gogoriki (Rpt) G Meet the Gogoriki - a circle of best friends whose zany adventures always result in loads of laughs! 07:00 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hip for kids? Join the team for the latest in gaming, sport, pop culture, movies, music and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:05 am Pokemon (Rpt) CC G Pokémon is the story of a young boy named Ash Ketchum. He received his first Pokémon at the age of 10 from Professor Oak and now is set out on his Pokémon Journey. 07:25 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hip for kids? Join the team for the latest in gaming, sport, pop culture, movies, music and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:30 am ICarly (Rpt) CC G Carly is a teenager who lives with her twenty-six year old brother and guardian Spencer, and produces her own web casts from a studio she constructed in the attic of her home. -

00001. Rugby Pass Live 1 00002. Rugby Pass Live 2 00003

00001. RUGBY PASS LIVE 1 00002. RUGBY PASS LIVE 2 00003. RUGBY PASS LIVE 3 00004. RUGBY PASS LIVE 4 00005. RUGBY PASS LIVE 5 00006. RUGBY PASS LIVE 6 00007. RUGBY PASS LIVE 7 00008. RUGBY PASS LIVE 8 00009. RUGBY PASS LIVE 9 00010. RUGBY PASS LIVE 10 00011. NFL GAMEPASS 1 00012. NFL GAMEPASS 2 00013. NFL GAMEPASS 3 00014. NFL GAMEPASS 4 00015. NFL GAMEPASS 5 00016. NFL GAMEPASS 6 00017. NFL GAMEPASS 7 00018. NFL GAMEPASS 8 00019. NFL GAMEPASS 9 00020. NFL GAMEPASS 10 00021. NFL GAMEPASS 11 00022. NFL GAMEPASS 12 00023. NFL GAMEPASS 13 00024. NFL GAMEPASS 14 00025. NFL GAMEPASS 15 00026. NFL GAMEPASS 16 00027. 24 KITCHEN (PT) 00028. AFRO MUSIC (PT) 00029. AMC HD (PT) 00030. AXN HD (PT) 00031. AXN WHITE HD (PT) 00032. BBC ENTERTAINMENT (PT) 00033. BBC WORLD NEWS (PT) 00034. BLOOMBERG (PT) 00035. BTV 1 FHD (PT) 00036. BTV 1 HD (PT) 00037. CACA E PESCA (PT) 00038. CBS REALITY (PT) 00039. CINEMUNDO (PT) 00040. CM TV FHD (PT) 00041. DISCOVERY CHANNEL (PT) 00042. DISNEY JUNIOR (PT) 00043. E! ENTERTAINMENT(PT) 00044. EURONEWS (PT) 00045. EUROSPORT 1 (PT) 00046. EUROSPORT 2 (PT) 00047. FOX (PT) 00048. FOX COMEDY (PT) 00049. FOX CRIME (PT) 00050. FOX MOVIES (PT) 00051. GLOBO PORTUGAL (PT) 00052. GLOBO PREMIUM (PT) 00053. HISTORIA (PT) 00054. HOLLYWOOD (PT) 00055. MCM POP (PT) 00056. NATGEO WILD (PT) 00057. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC HD (PT) 00058. NICKJR (PT) 00059. ODISSEIA (PT) 00060. PFC (PT) 00061. PORTO CANAL (PT) 00062. PT-TPAINTERNACIONAL (PT) 00063. RECORD NEWS (PT) 00064. -

Guru Guide™ to Entrepreneurship Boyett *I-Xvi 001-171 9/18/00 15:30 Page Ii Boyett *I-Xvi 001-171 9/18/00 15:30 Page Iii

B u s i n e s s C u l i n a r y A r c h i t e c t u r e C o m p u t e r G e n e r a l I n t e r e s t C h i l d r e n L i f e S c i e n c e s B i o g r a p h y A c c o u n t i n g F i n a n c e M a t h e m a t i c s H i s t o r y S e l f - I m p r o v e m e n t H e a l t h E n g i n e e r i n g G r a p h i c D e s i g n A p p l i e d S c i e n c e s P s y c h o l o g y I n t e r i o r D e s i g n B i o l o g y C h e m i s t r y WILEYe WILEY JOSSEY-BASS B O O K PFEIFFER J.K.LASSER CAPSTONE WILEY-LISS WILEY-VCH WILEY-INTERSCIENCE Boyett_*i-xvi_001-171 9/18/00 15:30 Page i The Guru Guide™ to Entrepreneurship Boyett_*i-xvi_001-171 9/18/00 15:30 Page ii Boyett_*i-xvi_001-171 9/18/00 15:30 Page iii The Guru Guide™ to Entrepreneurship A Concise Guide to the Best Ideas from the World’s Top Entrepreneurs Joseph H. -

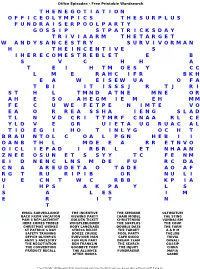

T H E N E G O T I a T I O N O F F I C E O L Y M P I C S T H E S U R P L U S F U N D R a I S E R P O O L P a R T Y G O S S I

Office Episodes - Free Printable Wordsearch THENEGOTIATION OFFICEOLYMPICS THESURPLUS FUNDRAISERPOOLPARTY GOSSIPSTP ATRICKSDAY TRIVIAARMTHETA RGET WANDYSANCESTRY SURVIVORMAN HTHEI NCENTIVES IHERECOMESTREBLET EB SV CHH A TEI HTMOESY CC LME RAHCIFR BKH EAWEI SEWUAO FA TBIIT ISSSJRTJ RI STHL TMNDATNEMNE OR AHESO AHEGMIEMEH MM FECUWE FETPENIMTE VO EAORREA SSHAIENG SLAD TLNVDCR ITTMRFCNAA RLCE YLDVEGR UIETAUGRUACA L TIOEGIHO TINLYGOC HT BRAUNTOLCOA LPGNHEBI I OANBTHL MDEEARR ETNVO OICLIEFADI RBRLET NHAAN ZNEEOSUNETS SYYTC FENM EIDNENCLNS MDEFU RCDA CNAAREUDETA OTADE AOAF RGTRURI PIBOR NULI UECNT WCRBB KPIA IHPS AKPAY LS SA LES IM ER IT N T EMAIL SURVEILLANCE THE INCENTIVE THE SEMINAR ULTIMATUM BACK FROM VACATION VIEWING PARTY CHAIR MODEL THE STING PAM S REPLACEMENT GOLDEN TICKET CHRISTENING VANDALISM HERE COMES TREBLE WHISTLEBLOWER THE SURPLUS THE COUP CHRISTMAS WISHES BODY LANGUAGE DOUBLE DATE THE FARM ST PATRICK S DAY STRESS RELIEF THE TARGET AARM SAFETY TRAINING BOOZE CRUISE POOL PARTY THE JOB OFFICE OLYMPICS SURVIVOR MAN CAFE DISCO TRIVIA ANDY S ANCESTRY FUN RUN PART DREAM TEAM DIWALI THE NEGOTIATION BEN FRANKLIN THE SEARCH GOSSIP THE CONVENTION GOODBYE TOBY THE INJURY CHINA PRODUCT RECALL THE ALLIANCE FUNDRAISER MAFIA AFTER HOURS SABRE Free Printable Wordsearch from LogicLovely.com. Use freely for any use, please give a link or credit if you do. Office Episodes - Free Printable Wordsearch ACNIGHT OUTPROMOS SP NAT AM GSHTHEDELIVE RY MU RIET DTEH YNDGH ESVCS AOUEESUITWARE HOUSEXIIETS T NNETD ERRHNON DILTE THEBOATMSHDTUAL U YGYP ACDHTNTO -

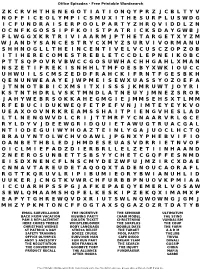

Z K C R V H T H E N E G O T I a T I O N Q Y P R Z J C B L T Y V N O F F I C E O L Y M P I C S M U X I T H E S U R P L U S W

Office Episodes - Free Printable Wordsearch ZKCRVHTHENEGOTIATIO NQYPRZJCBLTYV NOFFICEOLYMPICSMUXI THESURPLUSWDG ICFUNDRAISERPOOLPAR TYZHRQVIDDLZN OCNFKGOSSIPFKOISTPA TRICKSDAYGWBJ FLWGGXKRTRIVIAARMJP THETARGETXYZM WJANDYSANCESTRYCXMYZ SURVIVORMANU SHHNOGLLTHEINCENTIV ELVCUSCZOPZOB ITIHERECOMESTREBLET CCDLEPNEIKOBC PTTSQPOVRVBWCCGOSUWHAC HHGAHLXMAN NSZETIFREKISNHHLTMF OESBYXWKIOUCC UHWUILSCMSZEDDFRAHCK IFRNTFGESBKH QENUNWEAAYEJWPMEISEWX UASSYOZOEFA JTNNOTBBICXMSITXIS SSJKMRUWTJOYRI KSTNTHDRLVSKTMNDLATN EUYJMNEZSROR JAHYWEBRSOKKAHEGMGIE JMMSEHSXTLMM RFEBUCIDUKWEQFETPEFV NJIMTEYEYKVO UEAXOOVNRKREAMSSHAIT PIENGVHESLAD LTLNENGWVDLCRIJTTMR FYCNAARVRLGCE RYLDYVJDEEWGRIDQUIE TAWUGTRUACGAL NTIODEGUIWYHOAZTEIN LYGAJUOCLHCTQ BRAUYNTOLWCHVOAWLJPGN XYPHEBVIFIO OANBETHBLEDJHMDESEUA SVDRRIETNVOF OICLMIEFADZDIERBRL LELZETIINHAAND ZNEEROSUNBETTSBSYYCH ETCGQFFESNMD EISDXNENCFLNSCMYDEZW FUJMZIRCXDAE CNNAVTAREUDETAQOQXTAD ENOUCAORAFL RGTTKQRUVLRIPIBUMI EORYBWIANUHLID UUKERJCNGTKVWRCHFURBB PNUOVKPMIAA ICCUARHPSSPGJAFKEPA EQYEMERLVOSAW SEWLQMAAMSHQFELKESKIP ZEKQXIMAMXP EAPYTGHREWQVDXRIUTSWL NQWOWNGJGMJ MHZYPKMTONCFFOGTAXSQG AZOZRTDATYB EMAIL SURVEILLANCE THE INCENTIVE THE SEMINAR ULTIMATUM BACK FROM VACATION VIEWING PARTY CHAIR MODEL THE STING PAM S REPLACEMENT GOLDEN TICKET CHRISTENING VANDALISM HERE COMES TREBLE WHISTLEBLOWER THE SURPLUS THE COUP CHRISTMAS WISHES BODY LANGUAGE DOUBLE DATE THE FARM ST PATRICK S DAY STRESS RELIEF THE TARGET AARM SAFETY TRAINING BOOZE CRUISE POOL PARTY THE JOB OFFICE OLYMPICS SURVIVOR MAN CAFE DISCO TRIVIA ANDY S ANCESTRY FUN -

Approved: | Lei

IMPACT OF QUICK RESPONSE TECHNOLOGY BASED ATTRIBUTES ON CONSUMER SATISFACTION/DISSATISFACTION AMONG FEMALE APPAREL CONSUMERS by Eunju Ko Copyright i995 Eunju Ko Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Clothing and Textiles APPROVED: | LEI Doris H. Kincade, Chairman Assistant Professor Clothing and Textiles ATZB Marjorie JZT. Norton . Associate Professor and Dept. Head Assistant Professor Clothing and Textiles “yt WOM, Clint W. Coakley Professor Assistant Professor Marketin Statistics June 1995 Blacksburg, Virginia Key Words: Quick Response Technology, Consumer satisfaction, Apparel Wotecapsrttenes * IMPACT OF QUICK RESPONSE TECHNOLOGY BASED ATTRIBUTES ON CONSUMER SATISFACTION/DISSATISFACTION AMONG FEMALE APPAREL CONSUMERS by Eunju Ko Doris H. Kincade, Chairman Clothing and Textiles (ABSTRACT) The purpose of this research was to test a conceptual model which examines consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction (CS/D) with apparel retail stores and to investigate the moderating effects of shopping orientations and store type on confirmation/disconfirmation (C/DC) about quick response technologies (QRT) based attributes and CS/D with a retail store. Shopping orientation included fashion, economic, and time orientations. Store type included specialty chain, department, discount, and small independent stores. The conceptual framework for this study was based on retail strategic planning (Berman & Evans, 1992; Cory, 1988) and consumer satisfaction theory (Oliver, 1980). A convenience sample of 200 female apparel consumers was selected from a southeast city in the United States. The survey design employed a structured questionnaire with some open-ended questions. A questionnaire was pilot tested for content validity and instrument reliability. -

School District to Ask for $1.2M Tax Increase

Former Sumter standout Barnes step closer to the Major Leagues B1 TUESDAY, JUNE 4, 2019 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents ‘Make good School district to ask decisions’ for $1.2M tax increase in the water $1.6M surplus projected after $770K saved with ‘exemptions’ ruling this summer BY BRUCE MILLS ports through April 30, 2019, at tion Agency website. [email protected] Monday’s school board advisory “We are now considered ‘met BY DANNY KELLY Finance Committee meeting at with exceptions’ on the initial [email protected] Sumter School District will the district office. finding,” Miller said. end this fiscal year with a pro- Regarding a pending $770,000 Finance Committee Chairman jected net income of $1.6 million, maintenance-of-effort finding, Johnny Hilton and other com- With gruelingly hot temperatures al- $770,000 more than expected Miller said the state Department mittee members took that as ready bestowing themselves upon us, thanks to not having to pay the of Education accepted exemp- “good news,” they said at the one of the best ways to cool off may be state back for local spending on tion actions by the district, and meeting. a federal education program. now the district has been ruled Miller went on to discuss next at the beach, lake or pool. This year’s projected $1.6 mil- in compliance on local funding year’s budget, which goes before While one should always have fun, it’s lion surplus would raise the dis- with maintenance of effort on a Sumter County Council today. -

Assessment of the Flight Test Methodology and Separation Characteristics of the AGM-154A Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW) on the F/A-18C/D Hornet

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2006 Assessment of the Flight Test Methodology and Separation Characteristics of the AGM-154A Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW) on the F/A-18C/D Hornet Daniel Keith Hinson University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Aerospace Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Hinson, Daniel Keith, "Assessment of the Flight Test Methodology and Separation Characteristics of the AGM-154A Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW) on the F/A-18C/D Hornet. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2006. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Daniel Keith Hinson entitled "Assessment of the Flight Test Methodology and Separation Characteristics of the AGM-154A Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW) on the F/A-18C/D Hornet." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Aviation Systems. Robert B. Richards, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Charles T. N. Paludan, George W. Masters Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Pilot Earth Skills Earth Kills Murphy's Law Twilight's Last Gleaming His Sister's Keeper Contents Under Pressure Day Trip Unity

Pilot Earth Skills Earth Kills Murphy's Law Twilight's Last Gleaming His Sister's Keeper Contents Under Pressure Day Trip Unity Day I Am Become Death The Calm We Are Grounders Pilot Murmurations The Dead Don't Stay Dead Hero Complex A Crowd Of Demons Diabolic Downward Spiral What Ever Happened To Baby Jane Hypnos The Comfort Of Death Sins Of The Fathers The Elysian Fields Lazarus Pilot The New And Improved Carl Morrissey Becoming Trial By Fire White Light Wake-Up Call Voices Carry Weight Of The World Suffer The Children As Fate Would Have It Life Interrupted Carrier Rebirth Hidden Lockdown The Fifth Page Mommy's Bosses The New World Being Tom Baldwin Gone Graduation Day The Home Front Blink The Ballad Of Kevin And Tess The Starzl Mutation The Gospel According To Collier Terrible Swift Sword Fifty-Fifty The Wrath Of Graham Fear Itself Audrey Parker's Come And Gone The Truth And Nothing But The Truth Try The Pie The Marked Till We Have Built Jerusalem No Exit Daddy's Little Girl One Of Us Ghost In The Machine Tiny Machines The Great Leap Forward Now Is Not The End Bridge And Tunnel Time And Tide The Blitzkrieg Button The Iron Ceiling A Sin To Err Snafu Valediction The Lady In The Lake A View In The Dark Better Angels Smoke And Mirrors The Atomic Job Life Of The Party Monsters The Edge Of Mystery A Little Song And Dance Hollywood Ending Assembling A Universe Pilot 0-8-4 The Asset Eye Spy Girl In The Flower Dress FZZT The Hub The Well Repairs The Bridge The Magical Place Seeds TRACKS TAHITI Yes Men End Of The Beginning Turn, Turn, Turn Providence The Only Light In The Darkness Nothing Personal Ragtag Beginning Of The End Shadows Heavy Is The Head Making Friends And Influencing People Face My Enemy A Hen In The Wolf House A Fractured House The Writing On The Wall The Things We Bury Ye Who Enter Here What They Become Aftershocks Who You Really Are One Of Us Love In The Time Of Hydra One Door Closes Afterlife Melinda Frenemy Of My Enemy The Dirty Half Dozen Scars SOS Laws Of Nature Purpose In The Machine A Wanted (Inhu)man Devils You Know 4,722 Hours Among Us Hide.. -

GES Principal Accused of Discrimination

JULY 15, 2010 GILFORD, N.H. - FREE GES principal accused of discrimination and sex discrimination with Superintendent MCAD in 2005, which was dismissed due to lack of vows to stand probable cause, was includ- ed as part of the response to behind Billings Onie’s 2007 MCAD com- BY MEGHAN SIEGLER plaint. It stated that investi- [email protected] gator Jeannine K. Rice found A complaint filed at the that there were at least 15 Norfolk Superior Court in “significant criticisms” Massachusetts against, from parents, students, col- among other parties, Gilford leagues and the administra- Elementary School Princi- tion regarding Onie’s atti- pal Jack Billings is being tude and behavior, and that called “an attempt to dis- Onie’s supervisor,Rabbi Stu- credit his name” by Gilford art Klammer, found Onie to Superintendent Paul DeMi- be “virtually impossible to nico, who stands ready to supervise.” PHOTO BY DONNA RHODES “defend his good name and “The Onies have been re- his good work.” lentless in their pursuit of Sweet summer treats Deborah Onie of Brook- causing personal suffering Gilford kids enjoy their summer days spent playing on the beach and taking swim lessons. What they like most is something their moms call line, Mass., has filed a com- or defaming the character of “Snack Shack Friday,” when they get to indulge in some sweet treats at Gilford Beach at the end of a long week. From left to right with their plaint against Billings, the anyone directly or vicari- Friday goodies are Hayley and brother Kelin Jeffreys, Charlotte Lehr, Addy Wernig, Jenna Pichette and her sister Alli, Sydni and Sophia Lehr, Maimonides School in ously involved with Ms. -

Ag-300-V29-All

NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY ORGANIZATION ORGANIZATION AC/323(SCI-244)TP/571 www.sto.nato.int STO AGARDograph 300 AG-300-V29 Flight Test Technique Series – Volume 29 Aircraft/Stores Compatibility, Integration and Separation Testing (Essais de compatibilité, d’intégration et de séparation des emports sur aéronef) This AGARDograph has been sponsored by the Systems Concepts and Integration Panel. Published September 2014 Distribution and Availability on Back Cover NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY ORGANIZATION ORGANIZATION AC/323(SCI-244)TP/571 www.sto.nato.int STO AGARDograph 300 AG-300-V29 Flight Test Technique Series – Volume 29 Aircraft/Stores Compatibility, Integration and Separation Testing (Essais de compatibilité, d’intégration et de séparation des emports sur aéronef) This AGARDograph has been sponsored by the Systems Concepts and Integration Panel. The NATO Science and Technology Organization Science & Technology (S&T) in the NATO context is defined as the selective and rigorous generation and application of state-of-the-art, validated knowledge for defence and security purposes. S&T activities embrace scientific research, technology development, transition, application and field-testing, experimentation and a range of related scientific activities that include systems engineering, operational research and analysis, synthesis, integration and validation of knowledge derived through the scientific method. In NATO, S&T is addressed using different business models, namely a collaborative business model where NATO provides a forum where NATO Nations and partner Nations elect to use their national resources to define, conduct and promote cooperative research and information exchange, and secondly an in-house delivery business model where S&T activities are conducted in a NATO dedicated executive body, having its own personnel, capabilities and infrastructure.