1 Gaston Lachaise (1920) [EE Cummings]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sculptures of Upper Summit Avenue

The Sculptures of Upper Summit Avenue PUBLIC ART SAINT PAUL: STEWARD OF SAINT PAUL’S CULTURAL TREASURES Art in Saint Paul’s public realm matters: it manifests Save Outdoor Sculpture (SOS!) program 1993-94. and strengthens our affection for this city — the place This initiative of the Smithsonian Institution involved of our personal histories and civic lives. an inventory and basic condition assessment of works throughout America, carried out by trained The late 19th century witnessed a flourishing of volunteers whose reports were filed in a national new public sculptures in Saint Paul and in cities database. Cultural Historian Tom Zahn was engaged nationwide. These beautiful works, commissioned to manage this effort and has remained an advisor to from the great artists of the time by private our stewardship program ever since. individuals and by civic and fraternal organizations, spoke of civic values and celebrated heroes; they From the SOS! information, Public Art Saint illuminated history and presented transcendent Paul set out in 1993 to focus on two of the most allegory. At the time these gifts to states and cities artistically significant works in the city’s collection: were dedicated, little attention was paid to long Nathan Hale and the Indian Hunter and His Dog. term maintenance. Over time, weather, pollution, Art historian Mason Riddle researched the history vandalism, and neglect took a profound toll on these of the sculptures. We engaged the Upper Midwest cultural treasures. Conservation Association and its objects conservator Kristin Cheronis to examine and restore the Since 1994, Public Art Saint Paul has led the sculptures. -

EDUCATION MATERIALS TEACHER GUIDE Dear Teachers

TM EDUCATION MATERIALS TEACHER GUIDE Dear Teachers, Top of the RockTM at Rockefeller Center is an exciting destination for New York City students. Located on the 67th, 69th, and 70th floors of 30 Rockefeller Plaza, the Top of the Rock Observation Deck reopened to the public in November 2005 after being closed for nearly 20 years. It provides a unique educational opportunity in the heart of New York City. To support the vital work of teachers and to encourage inquiry and exploration among students, Tishman Speyer is proud to present Top of the Rock Education Materials. In the Teacher Guide, you will find discussion questions, a suggested reading list, and detailed plans to help you make the most of your visit. The Student Activities section includes trip sheets and student sheets with activities that will enhance your students’ learning experiences at the Observation Deck. These materials are correlated to local, state, and national curriculum standards in Grades 3 through 8, but can be adapted to suit the needs of younger and older students with various aptitudes. We hope that you find these education materials to be useful resources as you explore one of the most dazzling places in all of New York City. Enjoy the trip! Sincerely, General Manager Top of the Rock Observation Deck 30 Rockefeller Plaza New York NY 101 12 T: 212 698-2000 877 NYC-ROCK ( 877 692-7625) F: 212 332-6550 www.topoftherocknyc.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Teacher Guide Before Your Visit . Page 1 During Your Visit . Page 2 After Your Visit . Page 6 Suggested Reading List . -

Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and Memorial

Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and Memorial American Battle Monuments Commission 1 2 LOCATION The Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and Memorial lies at the north edge of the town of Nettuno, Italy, which is immediately east of Anzio, 38 miles south of Rome. There is regular train service between Rome and Nettuno. Travel one way by rail takes a little over one hour. The cemetery is located one mile north of the Nettuno railroad station, from which taxi service is available. To travel to the cemetery from Rome by automobile, the following two routes are recommended: (1) At Piazza di San Giovanni, bear left and pass through the old Roman wall to the Via Appia Nuova/route No. 7. About 8 miles from the Piazza di San Giovanni, after passing Ciampino airport, turn right onto Via Nettunense, route No. 207. Follow the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery sign and proceed past Aprilia to Anzio, Nettuno and the cemetery. (2) At Piazza de San Giovanni, bear right onto the Via dell’ Amba Aradam to Via delle Terme de Caracalla and pass through the old Roman wall. Proceed along Via Cristoforo Colombo to the Via Pontina (Highway 148). Drive south approximately 39 miles along Highway 148 and exit at Campoverde/Nettuno. Proceed to Nettuno. The cemetery is located 5 ½ miles down this road. Adequate hotel accommodations may be found in Anzio, Nettuno and Rome. HOURS The cemetery is open daily to the public from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm except December 25 and January 1. It is open on host country holidays. -

Preserving the Mountain

Article: Preserving the mountain Author(s): Gerri Ann Strickler Source: Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Thirteen, 2006 Pages: 85-99 Compilers: Virginia Greene, Patricia Griffin, and Christine Del Re th © 2006 by The American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works, 1156 15 Street NW, Suite 320, Washington, DC 20005. (202) 452-9545 www.conservation-us.org Under a licensing agreement, individual authors retain copyright to their work and extend publications rights to the American Institute for Conservation. Objects Specialty Group Postprints is published annually by the Objects Specialty Group (OSG) of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works (AIC). A membership benefit of the Objects Specialty Group, Objects Specialty Group Postprints is mainly comprised of papers presented at OSG sessions at AIC Annual Meetings and is intended to inform and educate conservation-related disciplines. Papers presented in Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Thirteen, 2006 have been edited for clarity and content but have not undergone a formal process of peer review. This publication is primarily intended for the members of the Objects Specialty Group of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works. Responsibility for the methods and materials described herein rests solely with the authors, whose articles should not be considered official statements of the OSG or the AIC. The OSG is an approved division of the AIC but does not necessarily represent the AIC policy or opinions. Strickler AIC Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume 13, 2006 PRESERVING THE MOUNTAIN Gerri Ann Strickler Abstract Outdoor sculpture in New England requires a financial commitment of annual maintenance that is difficult for some owners to bear. -

The Whitney to Present American Legends: from Calder to O’Keeffe

THE WHITNEY TO PRESENT AMERICAN LEGENDS: FROM CALDER TO O’KEEFFE Charles Demuth, My Egypt, 1927. Oil on fiberboard, 35 3/4 × 30 in. (90.8 × 76.2 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 31.172 NEW YORK, December 3, 2012—Eighteen early to mid-century American artists who forged distinctly modern styles are the subjects of American Legends: From Calder to O’Keeffe, opening December 22 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Drawing from the Whitney’s permanent collection, the year-long show features iconic as well as lesser known works by Oscar Bluemner, Charles Burchfield, Paul Cadmus, Alexander Calder, Joseph Cornell, Ralston Crawford, Stuart Davis, Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, Edward Hopper, Gaston Lachaise, Jacob Lawrence, John Marin, Reginald Marsh, Elie Nadelman, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Joseph Stella. Curator Barbara Haskell has organized the museum’s holdings of each of these artists’ work into small-scale retrospectives. Many of the works included will be on view for the first time in years; others, such as Hopper’s A Woman in the Sun, Calder’s Circus, Jacob Lawrence’s War Series, and Georgia O’Keeffe’s Summer Days, are cornerstones of the Whitney’s collection. The show will run for a year in the museum’s fifth-floor Leonard & Evelyn Lauder Galleries and both the Sondra Gilman Gallery and Howard & Jean Lipman Gallery on the fifth-floor mezzanine. To showcase the breadth and depth of the Museum’s impressive modern art collection, a rotation will occur in May 2013 in order that other artists and works can be installed. -

The Lachaise Foundation

THE LACHAISE FOUNDATION Marie P. Charles, Director Frederick D. Ballou, Trustee Paula R. Hornbostel, Curator & Trustee Ronald D. Spencer, Trustee REMINDER February 21, 2012 www.frelinghuysen.org www.lachaisefoundation.org www.nyc.gov/parks GASTON LACHAISE’S LA MONTAGNE (THE MOUNTAIN) IN TRAMWAY PLAZA New York City’s Department of Parks & Recreation, The Lachaise Foundation and the Frelinghuysen-Morris Foundation are pleased to remind the public of the loan of La Montagne (The Mountain) modeled in 1934 by American Modernist sculptor Gaston Lachaise (1882-1935). The monumental bronze earth goddess lies at Tramway Plaza, located on Second Avenue between 59th and 60th Streets, where it is on loan to the New York City Parks Department from September 23rd until June 4th, 2012. Born in Paris in 1882, Gaston Lachaise studied sculpture at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, coming to the United States in 1906. He arrived in New York in 1912, and gained work with Paul Manship. He is known for his striking, voluptuous sculptures of women, they having been inspired by one woman, his muse model and wife Isabel. In 1935 the Museum of Modern Art gave Lachaise a retrospective exhibition of his work. He died later that year at the height of his career. The work of Lachaise’s work can be seen at Rockefeller Center on the 6th avenue facade of the GE building; in the sculpture garden at Moma (Floating Figure 1927) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and at the Whitney Museum. This bronze cast, the second in an edition of five, was made in 2002 by the Modern Art Foundry. -

Designs in Glass •

Steuben Glass, Inc. DESIGNS IN GLASS BY TWENTY-SEVEN CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS • • STEUBEN TH E CO LLE CT IO N OF DE S IG NS I N GLASS BY TWE N TY- SEVEN CONTE iPORARY ARTISTS • STEUBE l G L ASS lN c . NEW YORK C ITY C OP YTIT G l-IT B Y ST EUBEN G L ASS I NC . J ANUA H Y 1 9 40 c 0 N T E N T s Foreword . A:\1 A. L EWISOH Preface FRA K JEWETT l\lATHER, JR. Nalure of lhe Colleclion . J oH 1\1. GATES Number THOMAS BENTON 1 CHRISTIA BERARD . 2 MUIRHEAD BO E 3 JEA COCTEAU 4 JOH STEUART CURRY 5 SALVADOR DALI . 6 GIORGIO DE CHIRICO 7 A DRE DEHAI s RAO L DUFY 9 ELUC GILL 1 0 DU TCA T GRANT . 11 JOTI GREGORY 12 JEA HUGO 13 PETER HURD 14 MOISE KISLI. G 15 LEON KROLL . 16 MARIE LA RE TCIN 17 FERNAND LEGER. IS AlUSTIDE MAILLOL 19 PAUL MANSHIP 20 TT E TRI MATISSE 21 I AM OGUCHI. 22 GEORGIA O'KEEFFE 23 JOSE MARIA SERT . 24 PAVEL TClfELlTCHEW. 25 SID EY WAUGII 26 GHA T WOOD 27 THE EDITION OF THESE PIECE IS Lil\1ITED • STEUBEN WILL MAKE SIX PIECES FROM EACH OF THESE TWENTY SEVE DESIGNS OF WHICH ONE WILL BE RETAINED BY STEUBEN FOR ITS PERMANE T COLLECTIO TIIE REMAI I G FIVE ARE THUS AVAILABLE FOR SALE F 0 R E w 0 R D SAM: A. LEWISOHN This is a most important enterprise. To connecl lhe creative artist with every-day living is a difficult task. -

The Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection the Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection

THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection The Cornish Colony, located in the area of Cornish, New The Cornish Colony did not arise all of apiece. No one sat down at Hampshire, is many things. It is the name of a group of artists, a table and drew up plans for it. The Colony was organic in nature, writers, garden designers, politicians, musicians and performers the individual members just happened to share a certain mind- who gathered along the Connecticut River in the southwest set about American culture and life. The lifestyle that developed corner of New Hampshire to live and work near the great from about 1883 until somewhere between the two World Wars, American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The Colony is also changed as the membership in the group changed, but retained a place – it is the houses and landscapes designed in a specific an overriding aura of cohesiveness that only broke down when the Italianate style by architect Charles Platt and others. It is also an country’s wrenching experience of the Great Depression and the ideal: the Cornish Colony developed as a kind of classical utopia, two World Wars altered American life for ever. at least of the mind, which sought to preserve the tradition of the —Henry Duffy, PhD, Curator Academic dream in the New World. THE COLLECTION Little is known about the art collection formed by Augustus Time has not been kind to the collection at Aspet. Studio fires Saint-Gaudens during his lifetime. From inventory lists and in 1904 and 1944 destroyed the contents of the Paris and New correspondence we know that he had a painting by his wife’s York houses in storage. -

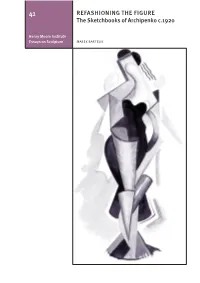

REFASHIONING the FIGURE the Sketchbooks of Archipenko C.1920

41 REFASHIONING THE FIGURE The Sketchbooks of Archipenko c.1920 Henry Moore Institute Essays on Sculpture MAREK BARTELIK 2 3 REFASHIONING THE FIGURE The Sketchbooks of Archipenko c.19201 MAREK BARTELIK Anyone who cannot come to terms with his life while he is alive needs one hand to ward off a little his despair over his fate…but with his other hand he can note down what he sees among the ruins, for he sees different (and more) things than the others: after all, he is dead in his own lifetime, he is the real survivor.2 Franz Kafka, Diaries, entry on 19 October 1921 The quest for paradigms in modern art has taken many diverse paths, although historians have underplayed this variety in their search for continuity of experience. Since artists in their studios produce paradigms which are then superseded, the non-linear and heterogeneous development of their work comes to define both the timeless and the changing aspects of their art. At the same time, artists’ experience outside of their workplace significantly affects the way art is made and disseminated. The fate of artworks is bound to the condition of displacement, or, sometimes misplacement, as artists move from place to place, pledging allegiance to the old tradition of the wandering artist. What happened to the drawings and watercolours from the three sketchbooks by the Ukrainian-born artist Alexander Archipenko presented by the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds is a poignant example of such a fate. Executed and presented in several exhibitions before the artist moved from Germany to the United States in the early 1920s, then purchased by a private collector in 1925, these works are now being shown to the public for the first time in this particular grouping. -

September 17, 2020 Contact: Paula Hornbostel | Director, Lachaise Foundation [email protected] | (212) 605-0380

PRESS RELEASE. For Immediate Release: September 17, 2020 Contact: Paula Hornbostel | Director, Lachaise Foundation [email protected] | (212) 605-0380 Gaston Lachaise Sculpture, Floating Woman, 1927, to be Installed in Hunter’s Point South Park On Thursday, September 24 at 3pm The Lachaise Foundation and the Hunters Point Parks Conservancy will be hosting a brief, socially distant unveiling ceremony, with short dance performance by local dance company Karesia Batan | The Physical Plant to celebrate the addition of Floating Woman in Hunter’s Point South Park. Members of the press are invited to attend. Event will occur by the sculpture, near the intersection of 51st Ave. and Center Blvd. Follow by Live- stream: @Paula_Hornbostel_LachaiseFoundation Long Island City, NY – Hunters Point Parks Conservancy and the Lachaise Foundation are thrilled to announce the temporary installation of Gaston Lachaise’s Floating Woman (Floating Figure) in Hunter’s Point South Park. The work is one of Lachaise’s best-known, monumental works dating from the late twenties. The buoyant, expansive figure represents a timeless earth goddess, one Lachaise knew and sought to capture throughout his career. This vision was inspired by his wife, who was his muse and model, Isabel, that “majestic woman” who walked by him once by the Bank of the Seine. This work is a tribute to the power of all women, to ‘Woman,’ as the artist referred to his wife, with a capital W. Gaston Lachaise devoted himself to the human form, producing a succession of powerfully conceived nude figures in stone and bronze that reinvigorated the sculptural traditions of Auguste Rodin and Aristide Maillol. -

Press Release

Press Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact Troy Ellen Dixon Director, Marketing & Communications 203 413-6735 | [email protected] Face & Figure: The Sculpture of Gaston Lachaise Opens at the Bruce Museum on Saturday, September 22, 2012 Gaston Lachaise was more than a gifted sculptor of the human body. He was one of the finest portraitists of his age. Greenwich CT, September 13, 2012 – Face & Figure: The Sculpture of Gaston Lachaise features key examples of the artist’s work – many on loan from leading museums, private collections and the Lachaise Foundation – that reveal the full range of his vision, with special Press Release attention to the fascinating interchange between figural work and portraiture. Executive Director Peter Sutton notes that the sculpture of Gaston Lachaise is among the most powerful, recognizable and enduring of the early twentieth century. “The inspired sensuality of his buoyant nudes uplifts us all and the individuality of his portraits achieves an incisive statement of character scarcely rivaled in three dimensions. Face & Figure addresses these two aspects of the sculptor’s work and explores the intersection of their aims.” Running throughout this contemplative exhibition is the overriding narrative of the obsession Lachaise had with his muse, model and wife, Isabel Dutaud Nagle, who – sirenlike – inspired him to become that rare exception among artists of the 1920s and ’30s, an expatriate Frenchman in New York. Lachaise’s oeuvre is a sustained elaboration of his intense feeling for Nagle’s beauty. The series of great nudes that secured his Head of a Woman (Egyptian Head), 1922 Bronze,13 x 8 x 8 ¼ in. -

Biography, Thomas Lamont: the Ambassador from Wall Street

eA Library The Boston Letter from eAthenteum No. 105 JUNE 1994 Work Proceeds on 14 Beacon Street Wing OR those readers who missed the announcement in the Annual Report for 1993, it bears repeating that the Athenreum recently signed papers purchasing parts of the basement and sub-basement of the Congregational Building at no. 14 Beacon Street, which abuts the Athenreum's current residence at no. 10'h. It will come as no surprise to those of you who have over the years put up with wails and moans in these pages about dwindling space at lOlh that this announcement was greeted with a collective sigh of relief from the hearts and souls of both the staff and the Trustees. For now (or at least in an imaginable future) most, if not all, of our vol umes stored off -site in places such as Allston and Lawrence will be reunited with the rest of the collection, and many members of the staff who have worked for years in offices the size of closets will be able to spread out and breathe. And the Conservation Department will expand into new and enlarged space, enabling its staff to increase in number and more efficiently service some of our ailing books that have long been pa tiently waiting for treatment. The move is a milestone, representing the first real estate the A thenreum has pur chased in nearly 100 years. And, although much noise, dust, and some inconvenience will lie ahead, the initial phase of renovation is already complete, in the form of a "demising wall" which was installed in the 14 Beacon Street building to isolate the Athenreum's space from the upper floors of that building.