Benjamin Linfoot, 1840-1912: the Career of an Architectural Renderer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Bryn Mawr, 1683-1900

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr College Publications, Special Books, pamphlets, catalogues, and scrapbooks Collections, Digitized Books 1962 The History of Bryn Mawr, 1683-1900 Barbara Alyce Farrow Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_books Part of the Liberal Studies Commons, and the Women's History Commons No evidence was found that the copyright was renewed in the 28th year from the date of publication, as required for books published between 1923 and 1963 (see Library of Congress Copyright Office, How To Investigate the Copyright Status of a Work [Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, Copyright Office, 2004]). The book is therefore believed to be in the public domain. Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Custom Citation Farrow, Barbara Alyce. The History of Bryn Mawr, 1683-1900. Bryn Mawr, PA: Committee of Residents and Bryn Mawr Civic Association, 1962. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_books/14 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The HISTORY OF BRYN MAWR 1683-1900 Barbara Alyce Farrow THE HISTORY OF BRYN MAWR 1683 - 1900 Barbara Alyce Farrow Foreword by Catherine Drinker Bowen Pub lished by A Committee of Residents and The Bryn Mawr Civic Association Bryn M.:lw r, Pe nn sylvania 1962 This work is based on a thesis submitted in 1957 to Westminster College New Wilmington, Pennsylvania. Copyright © Barbara Alyce Farrow 1962 library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 62-13436 II To my grandmother, Mrs. -

Wyncote, Pennsylvania: the History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1985 Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb Doreen L. Foust University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Foust, Doreen L., "Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb" (1985). Theses (Historic Preservation). 239. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/239 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Foust, Doreen L. (1985). Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/239 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Foust, Doreen L. (1985). Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and -

9101 Germantown Avenue St. Michael's Hall, Located on a Large

St. Michael’s Hall, aka Alfred C. Harrison Country Estate – 9101 Germantown Avenue St. Michael’s Hall, located on a large wooded lot at the corner of Germantown and Sunset Avenues in Chestnut Hill, served as a summertime country retreat for its first sixty years. Between the time the house was built in the late 1850s, and 1924, St. Michael’s Hall was owned by three wealthy industrialists—William Henry Trotter (ownership 1855-1868), Henry Latimer Norris (ownership 1868-1884), and Alfred Craven Harrison (ownership 1884-1924). The Convent of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Chestnut Hill purchased the site in 1927, using it first as a school and then as a residence hall for nuns. The nuns vacated the property in September 2020, although it is still currently maintained by the Sisters of St. Joseph. 9101 Germantown Avenue, ca. 1903-1910 Courtesy of Chestnut Hill Conservancy Site Details • Built between 1855 and 1857, the house was originally rectangular in shape, measuring 40 by 43 feet. No architect has been attributed to the original building. • A small wing in the Gothic Revival style was added to the southeast elevation at an unknown date. • A small bay was added to the southwest (Germantown Avenue) elevation in 1896. • In 1899 two large wings in the Italianate style were added to the southeast and northeast elevations by architects Cope & Stewardson. • The 27,500 sq.ft. building sits on a lot of approximately 4 acres zoned RSD3, with 420’ of frontage bounded by Green Tree, Hampton, E Sunset, and Germantown. • The property is considered a “Significant” property in the Chestnut Hill National Register Historic District, but not listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. -

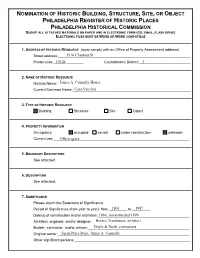

View Nomination

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________3910 Chestnut St ________ Postal code:_______________19104 Councilmanic District:__________________________3 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________James A. Connelly House ________ Current/Common Name:________Casa Vecchia___________________________________________ ________ 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________Office space ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION See attached. 6. DESCRIPTION See attached. 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1806 to _________1987 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________1866; reconstructed 1896 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:________________________________________Horace Trumbauer, architect _________ Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________Doyle & Doak, contractors _________ Original -

DUN DALE (Morris Estate) (Patterson Hall) Dundale Lane, .1 Mile West Of

DUN DALE HABS No. PA-6012 (Morris Estate) (Patterson Hall) Dundale Lane, .1 mile west of County Line Road Villanova Delaware County Pennsylvania PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY National Park Service Northeast Region Philadelphia Support Office U.S. Custom House 200 Chestnut Street Philadilphia, P.A. 19106 HABS PA HISTORJC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY ..Zs-VILA I - ;# DUNDALE (Morris Estate) (Patterson Hall) HABS No. PA-6012 ' Dundale Lane, .1 miles west of County Line Road Location: Villanova Deleware County Pennsylvania USGS Norristown P.I., 7.5 Minute Quadrangle Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates 17.470580.4932440 Present Owner: Villanova University, Villanova, Delaware County, Pennsylvania. Present Occupant: Unoccupied and scheduled for restoration and renovation in 1994. Significance: DUNDALE is significant for several reasons: Built in 1890 in a late Victorian eclectic style, it is one of the few remaining large country houses (including a barn and other out buildings) from that era in Villanova--or anywhere among Philadelphia's famous "Main Line" suburbs, of which Villanova forms a part. Both the house and its original occupants, the Theodore Morris family, illustrate the lives of socially prominent Philadelphians who used great wealth, derived mainly from local industries, to create country estates between the end of the American Civil War and the Great Depression of the 1930s. DUNDALE is also significant because its designer. Addison Hutton, was among Philadelphia's most accomplished nineteenth-century architects and probably the last of its great building -- designers who had no formal schooling in the -- profession of architecture. The Quaker faith of both the architect, Hutton, and the Morris family add yet another significant dimension in that their Quaker culture influenced DUNDALE's design, as well as the tenor of life in this spacious country house. -

Morris-Shinn-Maier Collection HC.Coll.1191

Morris-Shinn-Maier collection HC.Coll.1191 Finding aid prepared by Janela Harris and Jon Sweitzer-Lamme Other authors include: Daniel Lenahan, Kate Janoski, Jonathan Berke, Henry Wiencek and John Powers This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 28, 2012 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections July 18, 2011 370 Lancaster Ave Haverford, PA, 19041 610-896-1161 [email protected] Morris-Shinn-Maier collection HC.Coll.1191 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 7 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 8 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................. 15 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................16 Controlled Access Headings........................................................................................................................16 Collection Inventory................................................................................................................................... -

To Center City: the Evolution of the Neighborhood of the Historicalsociety of Pennsylvania

From "Frontier"to Center City: The Evolution of the Neighborhood of the HistoricalSociety of Pennsylvania THE HISToRICAL SOcIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA found its permanent home at 13th and Locust Streets in Philadelphia nearly 120 years ago. Prior to that time it had found temporary asylum in neighborhoods to the east, most in close proximity to the homes of its members, near landmarks such as the Old State House, and often within the bosom of such venerable organizations as the American Philosophical Society and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia. As its collections grew, however, HSP sought ever larger quarters and, inevitably, moved westward.' Its last temporary home was the so-called Picture House on the grounds of the Pennsylvania Hospital in the 800 block of Spruce Street. Constructed in 1816-17 to exhibit Benjamin West's large painting, Christ Healing the Sick, the building was leased to the Society for ten years. The Society needed not only to renovate the building for its own purposes but was required by a city ordinance to modify the existing structure to permit the widening of the street. Research by Jeffrey A. Cohen concludes that the Picture House's Gothic facade was the work of Philadelphia carpenter Samuel Webb. Its pointed windows and crenellations might have seemed appropriate to the Gothic darkness of the West painting, but West himself characterized the building as a "misapplication of Gothic Architecture to a Place where the Refinement of Science is to be inculcated, and which, in my humble opinion ought to have been founded on those dear and self-evident Principles adopted by the Greeks." Though West went so far as to make plans for 'The early history of the Historical Soiety of Pennsylvania is summarized in J.Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, Hisiory ofPhiladelphia; 1609-1884 (2vols., Philadelphia, 1884), 2:1219-22. -

\.\Aes Pennsylvania PA "It,- EL~PA S- ~

LYNNEWOOD HALL HABS NO. PA-t314f3 920 Spring Avenue Elkins Park Montgomery County \.\Aes Pennsylvania PA "it,- EL~PA s- ~ PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL A.ND DESCRIPTIVE Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service Department of the Intericn:· p_Q_ Box 37l2'i7 Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 I HABs Yt,r-" ... ELk'.'.PA,I HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY $- LYNNEWOOD HALL HABS No. PA-6146 Location: 920 Spring Avenue, Elkins Park, Montgomery Co., Pennsylvania. Significance: Lynnewood Hall, designed by famed Philadelphia architect Horace Trumbauer in 1898, survives as one of the finest country houses in the Philadelphia area. The 110-room mansion was built for street-car magnate P.A.B. Widener to house his growing family and art collection which would later become internationally renowned. 1 The vast scale and lavish interiors exemplify the remnants of an age when Philadelphia's self-made millionaire industrialists flourished and built their mansions in Cheltenham, apart from the Main Line's old society. Description: Lynnewood Hall is a two-story, seventeen-bay Classical Revival mansion that overlooks a terraced lawn to the south. The house is constructed of limestone and is raised one half story on a stone base that forms a terrace around the perimeter of the building. The mansion is a "T" plan with the front facade forming the cross arm of the "T". Enclosed semi circular loggias extend from the east and west ends of the cross arm and a three-story wing forms the leg of the 'T' to the north. The most imposing exterior feature is the full-height, five-bay Corinthian portico with a stone staircase and a monumental pediment. -

Horace Trumbauer Collection

Collection V36 Horace Trumbauer Collection ca. 1898-ca. 1947 2 boxes, 112 flat files, 16 rolled items, 4 lin. feet Contact: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107 Phone: (215) 732-6200 FAX: (215) 732-2680 http://www.hsp.org Inventoried by: Cary Majewicz Inventory Completed: May 2008 Restrictions: None © 2008 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. Horace Trumbauer collection Collection V36 Horace Trumbauer Collection, ca. 1898-ca. 1947 2 boxes, 112 flat files, 16 rolled items, 4 lin. feet Collection V36 Abstract Horace Trumbauer was born in Philadelphia in 1898 and became one of the city’s leading architects in the early middle part of the 20th century. He established his own firm in 1890 and, with a team of talented designers, began designing mostly private residences. In 1894, he completed “Grey Towers” for William Welsh Harrison in Glenside, Pennsylvania. Several years later, he designed “Chelton House” for George W. Elkins and “Lynnewood Hall” for P.A.B. Widener, both in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania. He also created residences in other states such as New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island. By the middle of his career, Trumbauer had begun designing commercial and public buildings as well. Locally, he designed the Philadelphia Museum of Art in Fairmount Park and parts of the Free Library. He also designed buildings for Jefferson Medical College and the Hahnemann Medical College. He designed several college and university buildings throughout the country, most notably much of Duke University’s campus in Durham, North Carolina. He also designed Widener Library at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. -

Four Historic Neighborhoods of Johnstown, Pennsylvania

HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY/HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD Clemson University 3 1604 019 774 159 The Character of a Steel Mill City: Four Historic Neighborhoods of Johnstown, Pennsylvania ol ,r DOCUMENTS fuBUC '., ITEM «•'\ pEPQS' m 20 1989 m clewson LIBRARY , j„. ft JL^s America's Industrial Heritage Project National Park Service Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/characterofsteelOOwall THE CHARACTER OF A STEEL MILL CITY: Four Historic Neighborhoods of Johnstown, Pennsylvania Kim E. Wallace, Editor, with contributions by Natalie Gillespie, Bernadette Goslin, Terri L. Hartman, Jeffrey Hickey, Cheryl Powell, and Kim E. Wallace Historic American Buildings Survey/ Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Washington, D.C. 1989 The Character of a steel mill city: four historic neighborhoods of Johnstown, Pennsylvania / Kim E. Wallace, editor : with contributions by Natalie Gillespie . [et al.]. p. cm. "Prepared by the Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record ... at the request of America's Industrial Heritage Project"-P. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Historic buildings-Pennsylvania-Johnstown. 2. Architecture- Pennsylvania-Johnstown. 3. Johnstown (Pa.) --History. 4. Historic buildings-Pennsylvania-Johnstown-Pictorial works. 5. Architecture-Pennsylvania-Johnstown-Pictorial works. 6. Johnstown (Pa.) -Description-Views. I. Wallace, Kim E. (Kim Elaine), 1962- . II. Gillespie, Natalie. III. Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record. IV. America's Industrial Heritage Project. F159.J7C43 1989 974.877-dc20 89-24500 CIP Cover photograph by Jet Lowe, Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record staff photographer. The towers of St. Stephen 's Slovak Catholic Church are visible beyond the houses of Cambria City, Johnstown. -

Community Builders

Architectural Lighting Design Awards Architensions A Tax Credit for Green Projects architectmagazine.com BLA A Grand Rapids Hub by UrbanWorks The Journal of The American LAMAS Crowding, Density, and COVID-19 Institute of Architects Flipping Agency in Architecture Community Builders Gathering has taken on a whole new meaning, but the winners of the AIA Awards for Architecture show that thoughtful design will always foster connection. treat your building like a work of art photo by Javier Callejas Today’s LEDs may last up to 50,000 hours, but then again, Kalwall will be harvesting sunlight into museum-quality daylighting™ without using any energy for a lot longer than that. The fact that it also filters out most UV and IR wavelengths, while insulating more like a roof than a skylight, is just a nice bonus. ® FACADES | SKYROOFS | SKYLIGHTS | CANOPIES schedule a technical consultation at KALWALL.COM FIRE RATED GLASS #1 MADE IN THE USA USA-MADEUSA-MADE ISIS BESBEST T PROJECT: ORLANDO VA MEDICAL CENTER IN ORLANDO, FL ARCHITECT: RLF ARCHITECTS PRODUCTS: FIRE RESISTIVE & HURRICANE RATED SUPERLITE II-XL 60 & 120 IN GPX HURRICANE WALL SYSTEM SAFTI FIRST is the first and only vertically integrated USA-manufacturer of fire rated glass and framing today, offering competitive pricing and fast lead times. UL and Intertek listed. All proudly USA-made. Visit us today at safti.com to view our complete line of fire rated glass, doors, framing and floors. To learn why SAFTI FIRST is the #1 USA-manufacturer of fire rated glass, watch our new video at safti.com/usa-made. -

Collection V36

Collection V36 Horace Trumbauer Collection ca. 1898-ca. 1947 2 boxes, 112 flat files, 16 rolled items, 4 lin. feet Contact: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107 Phone: (215) 732-6200 FAX: (215) 732-2680 http://www.hsp.org Inventoried by: Cary Majewicz Inventory Completed: May 2008 Restrictions: None © 2008 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. Horace Trumbauer collection Collection V36 Horace Trumbauer Collection, ca. 1898-ca. 1947 2 boxes, 112 flat files, 16 rolled items, 4 lin. feet Collection V36 Abstract Horace Trumbauer was born in Philadelphia in 1868 and became one of the city’s leading architects in the early middle part of the 20th century. He established his own firm in 1890 and, with a team of talented designers, began designing mostly private residences. In 1894, he completed “Grey Towers” for William Welsh Harrison in Glenside, Pennsylvania. Several years later, he designed “Chelton House” for George W. Elkins and “Lynnewood Hall” for P.A.B. Widener, both in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania. He also created residences in other states such as New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island. By the middle of his career, Trumbauer had begun designing commercial and public buildings as well. Locally, he designed the Philadelphia Museum of Art in Fairmount Park and parts of the Free Library. He also designed buildings for Jefferson Medical College and the Hahnemann Medical College. He designed several college and university buildings throughout the country, most notably much of Duke University’s campus in Durham, North Carolina. He also designed Widener Library at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.