Photography 2: Documentary, Fact and Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

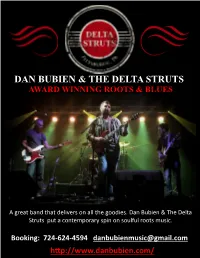

Dan Bubien & the Delta Struts

DAN BUBIEN & THE DELTA STRUTS AWARD WINNING ROOTS & BLUES A great band that delivers on all the goodies. Dan Bubien & The Delta Struts put a contemporary spin on soulful roots music. Booking: 724-624-4594 [email protected] http://www.danbubien.com/ What You Get…… Emotionally evoking songs driven by the dynamic guitar playing duo of Dan Bubien and Shawn Mazzei, along with Bubien’s soulful gritty vocals. Their signature sound is highlighted by the precision playing and deep toned-full sound of drummer Mark Pollera and glued together by Christian Caputo’s steady, groove oriented bass playing. “Stunningly written and well crafted songs. Bubien squeezes every emotion from a song with his voice and guitar. As for the band, well they don't get any better than this!” “Bubien's vocals growl and rise and fall as if he is howling at a full moon.” “Bubien certainly possesses an extraordinary voice that has a power but also a more soulful side that lends itself well to all that is required to send each and every song to dizzying heights!” “Bubien wailing as if his life depended on it stripping back his soul to allow his guitar to cut even deeper as it weeps and moans with a thousand stories. With every note and chord there are tears and pain that we can feel, Perfect Blues!!!” Peter Merrett, PBS106.7, Melbourne, Australia Quotables Bubien’s exquisite vocals and stunning slide guitar combines Glorious Soul drenched Blues that en- velops the listener in a cocoon of aural delight, and Hard rockin' Rock/Blues that drives along with a take no prisoner attitude that is full of swagger and bravado.” Peter Merrett, PBS106.7, Melbourne, Australia “Fine musicians, powerful songs, and albums of material that have a real listenability. -

Phoenix Bues Society

PHOENIX BLUES SOCIETY – BLUESBYTES It’s been eleven years since James Armstrong’s last release, an eternity in the music business. When he burst onto the scene in the mid 90’s with his debut recording for Hightone Records, he seemed destined to be the “next big thing,” but they don’t call this music the blues for nothing. Armstrong barely survived a robbery in 1997, in which he was nearly stabbed to death and his son was nearly killed. The stabbing affected his guitar playing, he compensated by learning to play slide guitar, but his songwriting and vocal talents were unscathed as he went on to record two fine subsequent albums for Hightone in 1998 and 2000. Eleven years later, Armstrong is now with CatFood Records, and his latest release, Blues At The Border, shows that his absence has been our loss. He’s still writing some impressive tunes. The humorous title track examines the difficulties musicians face traveling by air and overseas and was co-written with Armstrong by his girlfriend, Madonna Hamel, who lives in Canada. He also penned a few more conventional blues titles, including “Nothing Left To Say” and “Devil’s Candy.” “Young Man With The Blues” is a moving tribute to his father, a jazz musician who raised Armstrong as a single parent and gave him his love for music. Armstrong also covers a pair of tunes from Dave Steen (“High Maintenance Woman,” featuring a cameo from Hamel, and “Good Man, Bad Thing.”), along with a trio of songs from Catfood’s all-around man, bass player/producer Bob Trenchard (the cool blues shuffle, “Long Black Car,” “Somebody Got To Pay,” co-written by Sandy Carroll, and “Baby Can You Hear Me,” co-written by Kay Kay Greenwade). -

The News Letter September 2016

roundhillcommunitychurch.org Round Hill Round Hill Community Church Community Church @395roundhill The News Letter September 2016 PASTOR’S MESSAGE SEPTEMBER EVENTS On many summer nights of my RALLY SUNDAY childhood, my family and I would September 11 drag some of the patio furniture out to the middle of the open field next Worship at 10:00 a.m. to our home, eat dinner, and talk Picnic and Fun at 11:00 a.m. well past midnight. Those late night conversations under the stars often drifted in the direction of big questions. What’s out there in the star speckled night sky? What in the world are we up to? What makes life worth living? During this past year the Center for Faith Devel- opment at Round Hill Community Church began to wonder how we might form a faith formation pro- gram around one of these big life questions. In that process of discernment, we discovered that the Center for Faith and Culture at Yale University developed for Games Bouncy Castle its students a new class entitled “Life Worth Living.” Round Hill Express Train Rides That captured our imagination: what would it mean Ben’s Ice Cream Truck to examine this theme as a congregation that lives at the intersection of faith and culture? And to do so for an entire year! To design the program, we enlisted the counsel of John Roberto, an outstanding educator who helps communities across the nation with these kinds of endeavors. So this year we will have an opportunity to learn and grow in faith together by participating in a unique educational program that has been designed especially for Round Hill Community Church. -

The Advocate Student Publications

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History The Advocate Student Publications 2-19-1975 The Advocate The Advocate, Fordham Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/student_the_advocate Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation The Advocate, Fordham Law School, "The Advocate" (1975). The Advocate. Book 63. http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/student_the_advocate/63 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Advocate by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Three slates compete for S8~ offices by Aaron Reichel and Jim O'Hare The annual campaign for SBA each office. Each candfdate alongside McGregor are Brian Interviews Available Frawley Kevin Frawley: Frawley feels offices officially began Tuesday, belonged to a ticket and there Sullivan 1A for Vice President, The Advocate has conducted were no independents in the Patsy Smithwick 1A for that a united student body could February 11 when twelve names lengthy interviews with each one .....: .: ..-:- running. Polling has been set for of the twelve candidates. These Monday and Tuesday, February interviews are on tape and are 24 and 25. The three nominees available at the Advocate office I for President of the SBA are for anyone interested. - Kevin Frawley, 2A, Mike Moore 2B, and-Stu McGregor, 3E. The All the candidates expressed slate headed by Frawley includes belief in their own tickets, _and Bill Brennen 2A for Vice "the ticket system generally, on President, Noel Caraccio 2A for the theory that one can get more Secretary, and Frank Allocca 2A, done when working with people for Treasurer. -

Thursday, May 21, 2020

Thursday, May 21, 2020 Join Zoom Meeting zoom.us/j/97300581279 Meeting ID: 973 0058 1279 a.) Agenda 3 b.) Minutes of April 16, 2020 Meeting 5 c.) Bill List 9 d.) Management Report 16 e.) Electronic Resources 18 f.) Virtual Programming 21 g.) Social Media 24 2 YONKERS PUBLIC LIBRARY AGENDA FOR BOARD MEETING MAY 21, 2020 MINUTES [ACTION ITEM] Approve Minutes of Meeting April 16, 2020. MANAGEMENT REPORT UNION REPRESENTATIVE’S REPORT WLS REPORT PERSONNEL REPORT [ACTION ITEM] Ratify the following appointment: Luis Barcelo, Custodial Worker, $43,259.00/yr, eff. 5/15/2020 COMMITTEE REPORTS Finance, Budget & Planning- Maron, Jannetti, Puglia [ACTION ITEM] The following certificates will expire: 6/04/2020 Contributions Fund, Sterling National Bank, 14 mo. CD, $27,440.62, 2.75% 6/04/2020 Saunders Book Fund, Sterling National Bank, 15 mo. CD, $75,074.78, 2.75% 6/26/2020 Rita G. Murphy Memorial Fund, Sunnyside Federal Bank, 15 mo. CD, $5,507.13, 2.75% Employee Relations - Maron, Puglia Buildings & Grounds - Maron, Saraceno Policy – Maron, Ilarraza, Sabatino Fundraising & Development – Maron, Ilarraza, Mack Foundation Update RATIFY PAYMENT OF BILLS 3 [ACTION ITEM] Schedule #815 UNFINISHED BUSINESS FY21 Budget Update Library Reopening Policies & Procedures NEW BUSINESS EXECUTIVE SESSION NEXT MEETING DATE: Thursday, June 18, 2020 4 YONKERS PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD MEETING ELECTRONIC MEETING APRIL 16, 2020 ATTENDANCE TRUSTEES: Nancy Maron Josephine Ilarraza Stephen Jannetti Joseph Puglia John Saraceno Hon. Michael Sabatino LIBRARY DIRECTOR: Jesse Montero DEPUTY DIRECTOR: Susan Thaler BUSINESS MANAGER: Vivian Presedo ADMINISTRATIVE SECRETARY: James Hackett WLS BOARD REPRESENTATIVE: Tr. Puglia UNION REPRESENTATIVE: Brandon Neider, PC Tech. -

Jubilee Jubilee Is About Heartbreak and Overcoming Heartbreak

About Jubilee Jubilee is about heartbreak and overcoming heartbreak. You'll hear acoustic music, you'll hear music with the resonator. You'll definitely hear a more eclectic sound of music compared to Songs of a Renegade. The words are better and the playing is better. – Greg Sover About the Greg Sover Band Greg Sover is starting out 2018 on all cylinders! Greg’s new EP Jubilee is releasing on January 8th. And the Greg Sover Band will be competing at the International Blues Challenge in Memphis beginning January 17th, representing the Steel City Blues Society of Phoenixville, PA. Jubilee is the follow-up to the critically acclaimed Songs of a Renegade, Sover’s 2016 debut album, which put him on the map and announced that he is one of the top emerging blues artists in Philadelphia and beyond. Sover has gotten airplay not only on his hometown station, WXPN in Philadelphia, but Jubilee Credits on blues radio around the country and around the world. 1. Emotional 4:23 2. Jubilee 3:42 Sover’s success is due in large part to his band of three Philly veterans with 3. Hand on My Heart 5:59 extensive resumes – bassist, musical director and co-producer Garry Lee, 4. As the Years Go Passing By 4:42 guitarist Allen James and drummer Tom Walling. The three are best known as 5. I Give My Love 4:11 Deb Callahan’s solid backing band. 6. Temptation (live) 5:35 7. Hand on My Heart (short edit) 4:29 So if you haven’t heard Greg Sover, what are you waiting for? Greg Sover: lead guitars, resonator guitar, acoustic guitar and lead vocals Press Garry Lee: electric bass, background vocals and percussion “Promising young vocalist and guitarist Greg Sover, operating out of Allen James: electric guitar Philadelphia, is a highly charged interpreter of blues-rock who employs a Tom Walling: drums thunder-and-lightning style for most of the originals on his debut album. -

The Portrait in Photography

THE PORTRAIT IN PHOTOGRAPHY Edited by Graham Clarke THE PORTRAIT IN PHOTOGRAPHY Critical Views In the same series The New Museology edited by Peter Vergo Renaissance Bodies edited by Luey Gent and Nigel Llewellyn Modernism in Design edited by Paul Greenhalgh Interpreting Contemporary Art edited by Stephen Bann and William Allen THE PORTRAIT IN PHOTOGRAPHY Edited by Graham Clarke REAKTION BOOKS Published by Reaktion Books Ltd 1-5 Midford Place, Tottenham Court Road London W1P 9HH, UK First Published 1992 Copyright © Reaktion Books Ltd 1992 Distributed in USA and Canada by the University of Washington Press, PO Box 50096, Seattle, Washington 98145-5096, USA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Designed by Humphrey Stone Photoset by Wilmaset Ltd, Birkenhead, Wirral Printed and bound in Great Britain by Redwood Press Ltd, Melksham, Wiltshire British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data The portrait in photography. I. Clarke, Graham, 1948- 779. 2 ISBN 0-948462-29-9 ISBN 0-948462-30-2 pbk Contents Photographic Acknowledgements VI Notes on the Editor and Contributors VII Introduction Graham Clarke 1 1 Nadar and the Photographic Portrait in Nineteenth-Century France Roger Cardinal 6 2 Erased Physiognomy: Theodore Gericault, Paul Strand and Garry Winogrand Stephen Bann 25 3 Julia Margaret Cameron: A Triumph over Criticism Pam Roberts 47 4 Public Faces, Private Lives: August Sander and the Social Typology of the Portrait Photograph Graham Clarke 71 5 Duchamp's Masquerades Dawn Ades 94 6 J. -

October & November 2015 Newsletter

magnacarta800th.com Newsletter / Issue 19 October & November 2015 OCTOBER & NOVEMBER 2015 NEWSLETTER New Magna Carta Grant Available From FCO The Foreign Office The ‘Magna Carta At the event, FCO Minister Baroness Anelay said, ‘Democracy under the Rule has announced a new Partnerships’ Fund: of Law is the best form of governance £100,000 fund offering • Small grants from a £100,000 pilot we know - and the longer-term trend fund now available via a bidding is towards countries wanting more British legal expertise to process. democratic governance, not less. counties around the world The UK Government is committed to • Grants will be administered by supporting this. that want to improve the the FCO’s Human Rights and Rule of Law and their Democracy Department; click here Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond, for bidding and information. MP for Runnymede, was the principal democratic processes. Speaker at the 2015 800th “Kick -off” • Bids will be accepted until the dinner at the Guildhall on the 12th 31st December. January, 2015. Click here to watch his speech. Conference at Beijing’s Renmin University Law School, but Exhibition Cancelled The Hereford Magna Carta was to go on Sir Robert Worcester writes... exhibition at Renmin University, but Chinese Last spring I was surprised and delighted to receive an invitation asking me to participate in a meeting in Beijing’s authorities did not provide approval in time Renmin University of China Law School. There were a number and the exhibition was therefore shown at the of legal historians both from Renmin and other Chinese Law residence of the British Ambassador. -

Brad Vickers&His

ManHatTone Music Proudly Presents A Brand New Release‘TravelingFool’ Man Hat Tone BRAD VICKERS & HIS MUSIC VESTAPOLITANS BRAD VICKERS learned on the job playing, touring, and recording with America’s blues and roots masters: Pinetop Perkins, Jimmy Rogers, Hubert Sumlin, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Odetta, Sleepy LaBeef, Rosco Gordon— to name only a few. Now his own group, The Vestapolitans, offer a good-time mix of originals and covers spanning blues, ragtime, skiffle, and more great American roots ‘n’ roll music. Their three CDs, “Traveling Fool” (2011), “Stuck With The Blues” (2010), and “Le Blues Hot” (2008) have met with terrific reviews, radio play on 250+ stations and are a hit with audiences everywhere! PRAISE for ‘TRAVELING FOOL’ “A set of “old school” blues and R&B that can’t fail to delight.”–Mick Rainsford, BLUES IN BRITAIN “Their best so far...This one will be hard to top.” –Graham Clarke, BLUES BYTES “A real success and a group to discover right away.” –Bernard Boyat, BLUES MAGAZINE FRANCE “An artist who quietly creeps under your skin.” –Rune Endal, BLUES NEWS NORWAY “Guardian of The Flame. An exciting recreation of those jug, ragtime, and old timey bands that first educated me in the 1960s and ’70s.” –Richard Ludmerer, BLUESWAX “Brad thanks those...from whom he has learned so well. They would be damn proud of this release.” –Chef Jimi, BLUES 411 “Vickers expertly conjures his heroes on originals..and receives superb support from his band.” –Bob Weinberg, JAZZ/BLUES FLA. “A true one-of-a-kind band, mixing and mastering wildly divergent styles, always sounding credible, and never mass-produced.” –Roger & Margaret White, BIG CITY RHYTHM & BLUES “This “rootsy” group settles themselves firmly in the “Masters” category. -

1968-06-02 University of Notre Dame Commencement Program

One Hundred and Twenty-third Commencement Exercises OFFICIAL JUNE ExERCISES THE UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE-DAME NoTRE DAME, INDIANA THE GRADUATE ScHOOL THE LAw ScHooL THE CoLLEGE oF ARTs AND LETTERS THE CoLLEGE OF SciENCE THE CoLLEGE oF ENGINEERING THE CoLLEGE oF BusiNEss ADMINISTRATION On the University Mall At 2:00p.m. (Central Daylight Time) Sunday, June 2, 1968 PROGRAM PRocESSIONAL CITATioNs FOR HoNORARY DEGREES by the Reverend John E. Walsh, C.S.C., Vice-President of Academic Affairs THE CoNFERRING oF HoNoRARY DEGREEs by the Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., President of the University PREsENTATION OF CANDIDATES FOR DEGREES by the Reverend Paul E. Beichner, C.S.C., Dean of the Graduate School by Joseph O'Meara Dean of the Law School by the Reverend Charles E. Sheedy, C.S.C., Dean of the College of Arts and Letters by Bernard Waldman Dean of the College of Science by Joseph C. Hogan Dean of the College of Engineering by Thomas T. Murphy Dean of the College of Business Administration THE CONFERRING OF DEGREES by the Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., President of the University PRESENTATION OF THE FACULTY AWARD PREsENTATION OF THE PRoFESSOR THOMAS MADDEN FAcuLTY AwARD COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS by Dr. James A. Perkins President of Cornell University . THE BLESSING by His Beatitude Maximos V Hakim . Degrees Conferred The University of Notre Dame announces the conferring of: The Degree of Doctor of Laws, honoris causa, on: His Beatitude Maximos V Hakim of Beirut, Lebanon Dr. James A. Perkins, Ithaca, New York Mr. Joseph A. Beirne, Washington, D.C. -

Cruel and Tender Tkit Final

THE REAL IN THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY PHOTOGRAPH Sponsored by UBS 5 JUNE – 7 SEPTEMBER 2003 Teacher and Group Leaders’ Kit Information and practical ideas for group visits 1. Introduction to the Exhibition Welcome to Tate Modern and to the Cruel and Tender exhibition. Visiting the exhibition Tickets are available in advance from Tate Ticketing, tel 020 How to use this kit 7887 3959, schools and group bookings line. Price for school This kit aims to help you carry out a successful visit to the groups – £4 each. exhibition. It includes useful contextual information and Please ask Tate Ticketing when you book tickets if you thematic cards to use with your students in the gallery or would like to book lunch and locker space (there is a limited classroom. Although it is aimed primarily at teachers visiting the amount available). exhibition and planning work with school students, Tate Modern As all exhibitions at Tate can be busy, please do not lecture welcomes group leaders from adult education, community to more than six students at a time. If you have a larger group education and many other learning organisations across many we suggest that you divide into smaller groups and use some varied disciplines. We have aimed to write this resource in a of the ideas and strategies we suggest in the kit. way that we hope will be useful to these wide audiences and do welcome your comments. How to structure your visit When visiting we suggest you introduce the exhibition to your The exhibition group in one of the concourse spaces, the Turbine Hall or the Cruel and Tender is the first exhibition at Tate Modern that is Clore Education Centre (see the Tate plan, available throughout dedicated to photography. -

Blues Bytes -- Graham Clarke

Graham Clarke June 21, 2019 Friday Blues Fix Blog Steve Conn has collaborated with a variety of musicians over his career, frequently with Sonny Landreth (appearing on Landreth’s recent Grammy-nominated effort Recorded Live In Lafayette). He’s also toured with Albert King, played accordion for Levon Helm, and even appeared on The Tonight Show with Shelby Lynne. A Louisiana native, Conn played small clubs in Louisiana, before moving to Colorado, where he formed the band Gris Gris. He also spent time in Los Angeles in that city’s music scene, returning to Colorado, where he was musical director for the NPR show eTown, before settling near Nashville. Conn plays keyboards, accordion, and alto sax, his singing voice is vulnerable and supremely soulful, reminiscent at times of Boz Scaggs, and he’s one heck of a songwriter. All of these talents can be savored on his latest, fifth overall, release, Flesh and Bone (Not Really Records). The opening track, “Famous,” is a New Orleans-styled track that finds Conn reflecting on his life, wanting the accolades he thinks he’s earned before it’s too late. Next is the title track, which is a jazzy shuffle that has a mid-career Miles Davis feel, followed by “Doing The Best That I Can” takes a regretful look at a broken relationship, and “You Don’t Know,” which is hopeful for better days ahead. “Annalee” is a sentimental ballad about a lost love from long ago, a theme that’s revisited later by another exceptional ballad, “Forever Seventeen,” a tune that will touch anyone who looks back and ponders what might have been.