Natural Hazards - Background Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology of the Wairarapa Area

GEOLOGY OF THE WAIRARAPA AREA J. M. LEE J.G.BEGG (COMPILERS) New International NewZOaland Age International New Zealand 248 (Ma) .............. 8~:~~~~~~~~ 16 il~ M.- L. Pleistocene !~ Castlecliffian We £§ Sellnuntian .~ Ozhulflanl Makarewan YOm 1.8 100 Wuehlaplngien i ~ Gelaslan Cl Nukumaruan Wn ~ ;g '"~ l!! ~~ Mangapanlan Ql -' TatarianiMidian Ql Piacenzlan ~ ~;: ~ u Wai i ian 200 Ian w 3.6 ,g~ J: Kazanlan a.~ Zanetaan Opoitian Wo c:: 300 '"E Braxtonisn .!!! .~ YAb 256 5.3 E Kunaurian Messinian Kapitean Tk Ql ~ Mangapirian YAm 400 a. Arlinskian :;; ~ l!!'" 500 Sakmarian ~ Tortonisn ,!!! Tongaporutuan Tt w'" pre-Telfordian Ypt ~ Asselian 600 '" 290 11.2 ~ 700 'lii Serravallian Waiauan 5w Ql ." i'l () c:: ~ 600 J!l - fl~ '§ ~ 0'" 0 0 ~~ !II Lillburnian 51 N 900 Langhian 0 ~ Clifdenian 5e 16.4 ca '1000 1 323 !II Z'E e'" W~ A1tonian PI oS! ~ Burdigalian i '2 F () 0- w'" '" Dtaian Po ~ OS Waitakian Lw U 23.8 UI nlan ~S § "t: ." Duntroonian Ld '" Chattian ~ W'" 28.5 P .Sll~ -''" Whalngaroan Lwh O~ Rupelian 33.7 Late Priabonian ." AC 37.0 n n 0 I ~~ ~ Bortonian Ab g; Lutetisn Paranaen Do W Heretauncan Oh 49.0 354 ~ Mangaorapan Om i Ypreslan .;;: w WalD8wsn Ow ~ JU 54.8 ~ Thanetlan § 370 t-- §~ 0'" ~ Selandian laurien Dt ." 61.0 ;g JM ~"t: c:::::;; a.os'"w Danian 391 () os t-- 65.0 '2 Maastrichtian 0 - Emslsn Jzl 0 a; -m Haumurian Mh :::;; N 0 t-- Campanian ~ Santonian 0 Pragian Jpr ~ Piripauan Mp W w'" -' t-- Coniacian 1ij Teratan Rt ...J Lochovlan Jlo Turonian Mannaotanean Rm <C !II j Arowhanan Ra 417 0- Cenomanian '" Ngaterian Cn Prldoli -

Contest 2015 Title: “Slip Rate and Paleoseismicity of the Kekerengu Fault: an Anchor Point for Deformation Rates and Seismic H

Contest 2015 Title: “Slip Rate and Paleoseismicity of the Kekerengu Fault: An anchor point for deformation rates and seismic hazard through central New Zealand” Leader: Timothy A. Little Organisation: Victoria University of Wellington Total funding (GST ex): $182,778 Title: Slip Rate and Paleoseismicity of the Kekerengu Fault: An anchor point for deformation rates and seismic hazard through central New Zealand Programme Leader: Timothy A. Little Affiliation: Victoria University of Wellington Co-P.I.: Russ Van Dissen (GNS Science) A.I.: Kevin Norton (VUW) Has this report been peer reviewed? Provide name and affiliation. Part of it: the paper by Little et al. was published in 2018 in the Bulletin of Seismological Society of America, which is a peer-reviewed international journal. Table of Contents: 1. Key Message for Media 2. Abstract 3. Introduction/ Background 4. Research Aim 1: Determining Kekerengu Fault Paleoseismic History 5. Research Aim 2: Determining the Late Quaternary Slip Rate of the Kekerengu Fault 6. Conclusions & Recommendations 7. Acknowledgments 8. References 9. Appendices Key Message for Media: [Why are these findings important? Plain language; 5 sentences.] Prior to this study, little scientific data existed about the rate of activity and earthquake hazard posed by the active Kekerengu Fault near the Marlborough coast in northeastern South Island. Our study was designed to test the hypothesis that this fault carries most of the Pacific-Australia plate motion through central New Zealand, and is a major source of seismic hazard for NE South Island and adjacent regions straddling Cook Strait—something that had previously been encoded in the NZ National Seismic Hazard Model. -

Variability in Single Event Slip and Recurrence Intervals for Large

Variability of single event slip and recurrence intervals for large magnitude paleoearthquakes on New Zealand’s active faults A. Nicol R. Robinson R. J. Van Dissen A. Harvison GNS Science Report 2012/41 December 2012 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Nicol, A.; Robinson, R.; Van Dissen, R. J.; Harvison, A. 2012. Variability of single event slip and recurrence intervals for large magnitude paleoearthquakes on New Zealand’s active faults, GNS Science Report 2012/41. 57 p. A. Nicol, GNS Science, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt 5040, New Zealand R. Robinson, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt 5040, New Zealand R. J. Van Dissen, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt 5040, New Zealand A. Harvison, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt 5040, New Zealand © Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2012 ISSN 1177-2425 ISBN 978-1-972192-29-0 CONTENTS LAYMANS ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................... IV TECHNICAL ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................... V KEYWORDS ......................................................................................................................... V 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 2.0 GEOLOGICAL EARTHQUAKES ................................................................................ 2 2.1 Data Sources ................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 -

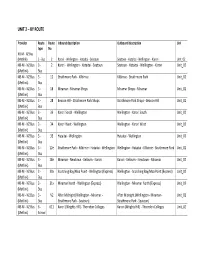

Unit 2 – by Route

UNIT 2 – BY ROUTE Provider Route Route Inbound description Outbound description Unit type No. NB -M - NZ Bus (Metlink) 3 - Bus 2 Karori - Wellington - Hataitai - Seatoun Seatoun - Hataitai - Wellington - Karori Unit_02 NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 2 Karori - Wellington - Hataitai - Seatoun Seatoun - Hataitai - Wellington - Karori Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 12 Strathmore Park - Kilbirnie Kilbirnie - Strathmore Park Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 18 Miramar - Miramar Shops Miramar Shops - Miramar Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 28 Beacon Hill - Strathmore Park Shops Strathmore Park Shops - Beacon Hill Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 33 Karori South - Wellington Wellington - Karori South Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 34 Karori West - Wellington Wellington - Karori West Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 35 Hataitai - Wellington Hataitai - Wellington Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 12e Strathmore Park - Kilbirnie - Hataitai - Wellington Wellington - Hataitai - Kilbirnie - Strathmore Park Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 18e Miramar - Newtown - Kelburn - Karori Karori - Kelburn - Newtown - Miramar Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 30x Scorching Bay/Moa Point - Wellington (Express) Wellington - Scorching Bay/Moa Point (Express) Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 31x Miramar North - Wellington (Express) Wellington - Miramar North (Express) Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - N2 After Midnight (Wellington - Miramar - After Midnight (Wellington - Miramar - Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus Strathmore Park - Seatoun) Strathmore Park - Seatoun) NB-M - NZ Bus 6 - 611 Karori (Wrights Hill) - Thorndon Colleges Karori (Wrights Hill) - Thorndon Colleges Unit_02 (Metlink) School Provider Route Route Inbound description Outbound description Unit type No. -

Archaeology of the Wellington Conservancy: Wairarapa

Archaeology of the Wellington Conservancy: Wairarapa A study in tectonic archaeology Archaeology of the Wellington Conservancy: Wairarapa A study in tectonic archaeology Bruce McFadgen Published by Department of Conservation P.O. Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand To the memory of Len Bruce, 1920–1999, A tireless fieldworker and a valued critic. Cover photograph shows a view looking north along the Wairarapa coastline at Te Awaiti. (Photograph by Lloyd Homer, © Insititute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences.) This report was prepared for publication by DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit; editing by Helen O’Leary and layout by Ruth Munro. Publication was approved by the Manager, Science & Research Unit, Science Technology and Information Services, Department of Conservation, Wellington. All DOC Science publications are listed in the catalogue which can be found on the departmental website http://www.doc.govt.nz © May 2003, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN 0–478–22401–X National Library of New Zealand Cataloguing-in-Publication Data McFadgen, B. G. Archaeology of the Wellington Conservancy : Wairarapa : a study in tectonic archaeology / Bruce McFadgen. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-478-22401-X 1. Archaeological surveying—New Zealand—Wairarapa. 2. Maori (New Zealand people)—New Zealand—Wairarapa— Antiquities. 3. Wairarapa (N.Z.)—Antiquities. I. New Zealand. Dept. of Conservation. II. Title. 993.6601—dc 21 ii Contents Abstract 1 1. Introduction 3 2. Geology and geomorphology 6 3. Sources of information 8 4. Correlation and dating 9 5. Off-site stratigraphy in the coastal environment 11 5.1 Sand dunes 12 5.2 Stream alluvium and colluvial fan deposits 13 5.3 Uplifted shorelines 14 5.4 Tsunami deposits 15 5.5 Coastal lagoon deposits 15 5.6 Correlation of off-site stratigraphy and adopted ages for events 16 6. -

Wellington Harbour Ferry Service Review 1

Attachment 1 to Report 07.394 Page 1 of 28 Wellington Harbour Ferry Service Review 1. Purpose To set out the results of a review of the Wellington Harbour Ferry Service. 2. Background The Council currently contracts East by West Ltd to provide a ferry service between Days Bay in Eastbourne and Queens Wharf in Wellington City. This contract will end in November 2007. In order to establish the service specifications for the next contract, a review of the ferry service was completed in May 2007. This report presents the results of the review. 2.1 History of the Wellington Harbour Ferry Service A ferry service between Days Bay and Queens Wharf in Wellington City has been operating since March 1989. This service has been run since that time by East by West Ltd – initially with the WestpacTrust ferry, which in 1990 was replaced with the current “City Cat” catamaran. The original service sailed between Days Bay and Queens Wharf, and in 1995 the route was expanded to include Matiu Somes Island, after the island was opened to the public as a Department of Conservation reserve. In 2002 a review of bus services in Eastbourne, Wainuiomata and Hutt Valley indicated potential for the ferry service to be expanded. Market research conducted in 2003 confirmed this, and concluded that reducing fares on the ferry, providing more frequent and later sailings, and providing more direct buses to the city were the most preferred options to improve public transport in Eastbourne. The option identified as being the most likely to bring new users to passenger transport was providing more frequent and later sailings. -

Before You Swim Again…

Is it safe to swim in Wellington and the Hutt Valley? Greater Wellington Regional Council and local councils monitor some of the Wellington region’s most popular beaches and rivers to determine their suitability for recreational activities such as swimming. We monitor eight freshwater and 34 coastal sites In the Wellington and Hutt Valley area. The results from this monitoring are compared to national guidelines and used to calculate an overall grade for each site. Results from the 2014/15 summer season Most of the swimming spots we monitor in Wellington and the Hutt Valley have good water quality. The best sites are Hutt River at Poets Park, Breaker Bay and Princess Bay which have an overall grade of ‘A’ and met the guideline for safe swimming on all occasions. The worst sites are at Island Bay, Owhiro Bay, Rona Bay, Hutt River at Melling and Wainuiomata River at Richard Prouse Park. These sites have an overall grade of ‘D’ and most recorded high bacterial counts on at least two or more occasions. Cyanobacteria (toxic algae) was a problem in some parts of the Hutt River over the summer. Cyanobacteria cover went over national guideline levels twice at Poets Park and three times at Silverstream. Very low risk of illness A 7% (3 sites) Low risk 43% (18 sites) B Moderate risk 33% (14 sites) C Caution 17% D (7 sites) Unsuitable for swimming 0% In the Wellington and Hutt Valley area, 3 sites (7%) are graded ‘A’, 18 sites (43%) are graded ‘B’, 14 sites (33%) are graded ‘C’ and 7 sites (17%) are graded ‘D’. -

Rongotai College

RONGOTAI COLLEGE PRINCIPAL’S NEWSLETTER Week 5, Term 2, 2018 COMING EVENTS Chem-Dry, had flowed into our short power outages Monday- basement classroom (A19), Wednesday this week as a result. We Monday 4 June basement corridor and storerooms, will phase turning heaters on before Queen’s Birthday holiday power switchboard and gas boilers school in the days ahead. and caused the problems we have Friday 8 June Rongotai Experience experienced. Classroom temperatures are now – no school for most students hovering between 12-17°, which while not ideal, does allow us to Tuesday 12 June keep the school open for instruction. Rongotai College Open Evening – no afternoon school for most students I certainly have appreciated the Wednesday 13 June goodwill of staff and students as St Patrick’s College Silverstream, sporting they are making do with this exchange at Silverstream situation. Thankfully, one of the gas Monday 18 June boilers is now working and it is Rongotai College Pasifika Parents’ Asosi at hoped the other will be by the end 6.30pm in the staffroom Water in A19 corridor of next week. Friday 22 June The water pipe was a relatively Winter Food Fair from 5.30pm in the Despite all of this, our boys seem to Renner Hall straightforward fix and electricity be coping well. For seniors, the into the school was reconnected on school year is more than one-third of Thursday 28 June Tuesday 22 May. It has taken about the way complete, and our deans, Board of Trustees’ meeting at 6pm in the a week for the basement to be dried Mackay Library academic mentors and classroom out. -

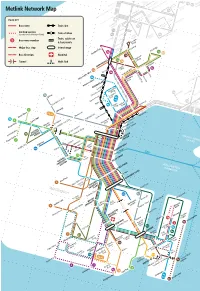

Metlink Network

1 A B 2 KAP IS Otaki Beach LA IT 70 N I D C Otaki Town 3 Waikanae Beach 77 Waikanae Golf Course Kennedy PNL Park Palmerston North A North Beach Shannon Waikanae Pool 1 Levin Woodlands D Manly Street Kena Kena Parklands Otaki Railway 71 7 7 7 5 Waitohu School ,7 72 Kotuku Park 7 Te Horo Paraparaumu Beach Peka Peka Freemans Road Paraparaumu College B 7 1 Golf Road 73 Mazengarb Road Raumati WAIKANAE Beach Kapiti E 7 2 Arawhata Village Road 2 C 74 MA Raumati Coastlands Kapiti Health 70 IS Otaki Beach LA N South Kapiti Centre A N College Kapiti Coast D Otaki Town PARAPARAUMU KAP IS I Metlink Network Map PPL LA TI Palmerston North N PNL D D Shannon F 77 Waikanae Beach Waikanae Golf Course Levin YOUR KEY Waitohu School Kennedy Paekakariki Park Waikanae Pool Otaki Railway ro 3 Woodlands Te Ho Freemans Road Bus route Parklands E 69 77 Muri North Beach 75 Titahi Bay ,77 Limited service Pikarere Street 68 Peka Peka (less than hourly, Monday to Friday) Titahi Bay Beach Pukerua Bay Kena Kena Titahi Bay Shops G Kotuku Park Gloaming Hill PPL Bus route number Manly Street71 72 WAIKANAE Paraparaumu College 7 Takapuwahia 1 Plimmerton Paraparaumu Major bus stop Train line Porirua Beach Mazengarb Road F 60 Golf Road Elsdon Mana Bus direction 73 Train station PAREMATA Arawhata Mega Centre Raumati Kapiti Road Beach 72 Kapiti Health 8 Village Train, cable car 6 8 Centre Tunnel 6 Kapiti Coast Porirua City Cultural Centre 9 6 5 6 7 & ferry route 6 H Coastlands Interchange Porirua City Centre 74 G Kapiti Police Raumati College PARAPARAUMU College Papakowhai South -

Prospectus for 2022

RONGOTAI COLLEGE PROSPECTUS Lumen accipe et imperti – Take the light and pass it on – Kapohia te ma-tauranga me ho- atu ra- RONGOTAI COLLEGE Lumen accipe et imperti Take the light and pass it on Kapohia te ma-tauranga me ho- atu ra- WELCOME TO RONGOTAI COLLEGE E nga- mana, e nga- waka, e nga- karangarangatanga o te motu, te-na koutou As parents and guardians of young males about to enter secondary education, you will want the best for your sons. Rongotai College has a proud tradition of achievement and excellence in academic, cultural and sporting activities. Rongotai College is a caring, supportive community, which is committed to helping every boy become the best he can be. It sets standards for boys to aspire to; it values tradition; it encourages excellence in all things; it recognises and celebrates the differences of our students; it provides opportunities for boys to expand their range of skills and abilities as they work through the process of realising their potential and becoming good men. We are proud of our college’s heritage and look forward to the future. I hope you will become a part of this future and experience something of the culture and spirit of this fine college. Nau mai haere mai. Kevin Carter, M.A.(Hons), Dip. Tchg. Principal WHY RONGOTAI COLLEGE? Rongotai College offers: • a roll size that allows every boy to be known and valued as an individual • a tradition of academic achievement and excellence • a top quality education for all students at all levels • a range of teaching programmes which meet the needs of all students • excellence in sporting and cultural activities • sound support for all students and fair, firm discipline • an experienced and highly-qualified teaching staff, made up of caring teachers who are involved in all areas of school life • opportunities and challenges for boys of all abilities and interests • a well-resourced school providing 21st century learning opportunities including BYOD. -

Fault Zone Parameter Descriptions, GNS Science Report 2012/19

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Litchfield, N. J.1; Van Dissen, R.1; Sutherland, R.1; Barnes, P. M.2; Cox, S. C.1; Norris, R.3; Beavan, R.J.1; Langridge, R.1; Villamor, P.1; Berryman, K.1; Stirling, M.1; Nicol, A.1; Nodder, S.2; Lamarche, G.2; Barrell, D. J. A.1; 4 5 1 2 1 Pettinga, J. R. ; Little, T. ; Pondard, N. ; Mountjoy, J. ; Clark, K . 2013. A model of active faulting in New Zealand: fault zone parameter descriptions, GNS Science Report 2012/19. 120 p. 1 GNS Science, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt 5040, New Zealand 2 NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Kilbirnie, Wellington 6241, New Zealand 3 University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand 4 University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand 5 Victoria University of Wellington, PO Box 600, Wellington 6140, New Zealand © Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2013 ISSN 1177-2425 ISBN 978-1-972192-01-6 CONTENTS ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................... IX KEYWORDS ........................................................................................................................ IX 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 2.0 ACTIVE FAULT ZONE AND PARAMETER DEFINITIONS ...................................... 25 2.1 DEFINITION OF AN ACTIVE FAULT ZONE .............................................................25 2.1.1 Definition of active .......................................................................................... -

A Practical Field Trip Lesson Plan to Harcourt Park, Upper Hutt Introduction

For Teachers: A practical field trip lesson plan to Harcourt Park, Upper Hutt This is a world class geological site showing the interaction between river erosion and an active fault. Getting there: The best place to start your visit is at California Park, which gives a good visual introduction to the landforms. Turn off the River Road (SH2) at Upper Hutt into Totara Park Road. Cross the first roundabout and continue over and right at the second into California Drive. After about 700 metres the California Park is visible on the left. You could also start your visit at Harcourt Park. From State Highway 2 at Brown Owl, Upper Hutt, turn into Akatarawa Rd - Harcourt Park will appear on the left after about 400m. Introduction What you can see there: As you drive towards California Park you will be driving down California Drive – you can see that houses on the left side of the road are higher than those on the right – you are driving along the fault scarp! California Drive shows how thoughtful urban planning can reduce earthquake risk. At California Park the topographic expression of the Wellington Fault is well defined. You can see an obvious straight scarp, this is called the fault scarp, and the ground surface has been uplifted on the northwest side. Between California Park and Harcourt Park, the Hutt River flows across the Wellington Fault at a right angle. Over many thousands of years the Hutt River has built up (aggraded) and cut down (eroded) sediment, these natural river cycles create step-like river terraces.