A Comparative Analysis of Character Animation and Performance Between American and Japanese Feature Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Animation: Types

Animation: Animation is a dynamic medium in which images or objects are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today most animations are made with computer generated (CGI). Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally differ from each other. Apart from short films, feature films, animated gifs and other media dedicated to the display moving images, animation is also heavily used for video games, motion graphics and special effects. The history of animation started long before the development of cinematography. Humans have probably attempted to depict motion as far back as the Paleolithic period. Shadow play and the magic lantern offered popular shows with moving images as the result of manipulation by hand and/or some minor mechanics Computer animation has become popular since toy story (1995), the first feature-length animated film completely made using this technique. Types: Traditional animation (also called cel animation or hand-drawn animation) was the process used for most animated films of the 20th century. The individual frames of a traditionally animated film are photographs of drawings, first drawn on paper. To create the illusion of movement, each drawing differs slightly from the one before it. The animators' drawings are traced or photocopied onto transparent acetate sheets called cels which are filled in with paints in assigned colors or tones on the side opposite the line drawings. The completed character cels are photographed one-by-one against a painted background by rostrum camera onto motion picture film. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Animation 1 Animation

Animation 1 Animation The bouncing ball animation (below) consists of these six frames. This animation moves at 10 frames per second. Animation is the rapid display of a sequence of static images and/or objects to create an illusion of movement. The most common method of presenting animation is as a motion picture or video program, although there are other methods. This type of presentation is usually accomplished with a camera and a projector or a computer viewing screen which can rapidly cycle through images in a sequence. Animation can be made with either hand rendered art, computer generated imagery, or three-dimensional objects, e.g., puppets or clay figures, or a combination of techniques. The position of each object in any particular image relates to the position of that object in the previous and following images so that the objects each appear to fluidly move independently of one another. The viewing device displays these images in rapid succession, usually 24, 25, or 30 frames per second. Etymology From Latin animātiō, "the act of bringing to life"; from animō ("to animate" or "give life to") and -ātiō ("the act of").[citation needed] History Early examples of attempts to capture the phenomenon of motion drawing can be found in paleolithic cave paintings, where animals are depicted with multiple legs in superimposed positions, clearly attempting Five images sequence from a vase found in Iran to convey the perception of motion. A 5,000 year old earthen bowl found in Iran in Shahr-i Sokhta has five images of a goat painted along the sides. -

The Animation Industry: Technological Changes, Production Challenges, and Global Shifts

THE ANIMATION INDUSTRY: TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGES, PRODUCTION CHALLENGES, AND GLOBAL SHIFTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hyejin Yoon, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Edward J. Malecki, Adviser Professor Nancy Ettlinger Adviser Graduate Program in Geography Professor Darla K. Munroe ABSTRACT Animated films have grown in popularity as expanding markets (such as TV and video) and new technologies (notably computer graphics imagery) have broadened both the production and consumption of cartoons. As a consequence, more animated films are produced and watched in more places, as new “worlds of production” have emerged. The animation production system, specialized and distinct from film production, relies on different technologies and labor skills. Therefore, its globalization has taken place differently from live-action film production, although both are structured to a large degree by the global production networks (GPNs) of the media conglomerates. This research examines the structure and evolution of the animation industry at the global scale. In order to investigate these, 4,242 animation studios from the Animation Industry Database are used. The spatial patterns of animation production can be summarized as, 1) dispersion of the animation industry, 2) concentration in world cities, such as Los Angeles and New York, 3) emergence of specialized animation cities, such as Annecy and Angoulême in France, and 4) significant concentrations of animation studios in some Asian countries, such as India, South Korea and the Philippines. In order to understand global production networks (GPNs), networks of studios in 20 cities are analyzed. -

Exploitation and Social Reproduction in the Japanese Animation Industry

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 5-2018 Exploitation and Social Reproduction in the Japanese Animation Industry James Garrett California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Behavioral Economics Commons, Labor Economics Commons, Labor History Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Garrett, James, "Exploitation and Social Reproduction in the Japanese Animation Industry" (2018). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 329. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/329 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exploitation and Social Reproduction in the Japanese Animation Industry James Garrett Senior Capstone School of Social, Behavior & Global Studies: Global Studies Major Capstone Advisors: Ajit Abraham & Richard Harris 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Global Studies department and faculty of California State University, Monterey Bay, for the dedication of their pursuit of understanding and acknowledging the complexities of global changes and shifts through an interdisciplinary curriculum. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Angie Tran and Dr. Robina Bhatti for helping me to develop a more complex understanding of advanced capitalist societies and the place of labor within those societies. I would also like to thank Dr. -

An Evaluation Study of Preferences Between Combinations of 2D-Look Shading and Limited Animation in 3D Computer Animation

Received May 1, 2015; Accepted October 5, 2015 An Evaluation Study of preferences between combinations of 2D-look shading and Limited Animation in 3D computer animation Matsuda,Tomoyo Kim, Daewoong Ishii, Tatsuro Kyushu University, Kyushu University, Kyushu University, Graduate school of Design Faculty of Design Faculty of Design [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract 3D computer animation has become popular all over the world, and different styles have emerged. However, 3D animation styles vary within Japan because of its 2D animation culture. There has been a trend to flatten 3D animation into 2D animation by using 2D-look shading and limited animation techniques to create 2D looking 3D computer animation to attract the Japanese audience. However, the effect of these flattening trends in the audience’s satisfaction is still unclear and no research has been done officially. Therefore, this research aims to evaluate how the combinations of the flattening techniques affect the audience’s preference and the sense of depth. Consequently, we categorized shadings and animation styles used to create 2D-look 3D animation, created sample movies, and finally evaluated each combination with Thurston’s method of paired comparisons. We categorized shadings into three types; 3D rendering with realistic shadow, 2D rendering with flat shadow and outline, and 2.5D rendering which is between 3D rendering and 2D rendering and has semi-realistic shadow and outline. We also prepared two different animations that have the same key frames; 24fps full animation and 12fps limited animation, and tested combinations of each of them for the evaluation experiment. -

Introduction

Introduction “this is the story of gerald mccloy and the strange thing that happened to that little boy.” These words, despite their singsong cadence and children’s-book diction, ushered in a new age of the American cartoon marked by a maturity widely perceived to be lacking in the animated shorts of Disney Studios and Warner Bros. Released in November 1950, Gerald McBoing Boing instantly made its production studio, United Productions of America (UPA), a major name in the Hollywood cartoon industry, netting the studio its first Oscar win two years after it began making shorts for Columbia’s Screen Gems imprint. Six years later, in 1956, every single short nominated in the Best Animated Short Film category was a UPA cartoon.1 Gerald McBoing Boing, a seven-minute Dr. Seuss–penned short about a small boy who finds himself unable to speak in words—only disruptive sound effects emerge from his mouth—became a box office sensation as well as a critical success. TheNew York Times observed, “Audiences have taken such a fancy to this talented young man that there has been a heap of inquiries about him and his future plans.”2 TheWashington Post called it “so refreshing and so badly needed . that its creators, United Productions and director Robert Cannon, rate major salutes,” and international publications such as the Times of India dubbed it “the first really fresh cartoon work since Disney burst on the scene.”3 The qualities that made UPA stand out—an abstract, graphic sensibility marked by simplified shapes, bold colors unmodulated by rounding effects or shadow, and a forceful engagement with the two-dimensional surface of the frame, as well as an insistence on using human characters—convinced audi- ences that it was aiming for an adult demographic while also retaining a childlike heart, positioning itself as a popular explorer of the human 1 Bashara-Cartoon Vision.indd 1 17/12/18 7:27 PM condition. -

Download but Allow In-App Purchases

FINDING CAMELITTLE: CHILDRENS TELEVISION IN A DIGITAL AGE ____________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University ____________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Graduation From the Honors Tutorial College With the degree of Bachelor of Science in Media Arts and Studies ____________________________________________________ By Ryan H. Etter June 2011 FINDING CAMELITTE 2 This thesis is dedicated to all those who have worked in children’s entertainment before me. From the Saturday morning cartoons, to feature length movies, I would like to thank the people who not only gave me a childhood, but also gave me passion and direction as an adult. FINDING CAMELITTE 3 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………4 CHAPTER 1: THE INDUSTRY………….………………………………………….8 CHAPTER 2: MAKING AN ANIMATED PROGRAM………………….………...16 CHAPTER 3: DEVELOPING CONTENT IN A DIGITAL AG…………………….24 CHAPTER 4: THE AUDIENCE………………..……………………………………43 CHAPTER 5: CAMELITTLE…………..……………………………………………51 REFERENCES………………….……………………………………………………73 CAMELITTLE PILOT DVD…………………………………………………Appendix FINDING CAMELITTE 4 Finding Camelittle: Children’s Television in a Digital Age Long ago and far away there was a land called Camelot. It was a kingdom ruled by the great king Arthur who was a virtuous and wise monarch. His reign was presented as idyllic and he was considered the model ruler. Many have used the imagery of Arthur’s Camelot to describe prosperous times in history, from the JFK presidency to the “Golden Age of Television.” For young children, the world is shaped by much smaller things than presidents or politics and, for myself; the world existed not only in my home or at school, but in the wonderfully imaginary places created in cartoons. -

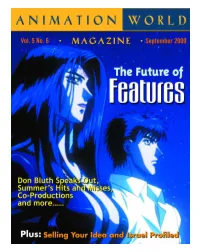

Cartoons Gerard Raiti Looks Into Why Some Cartoons Make Successful Live-Action Features While Others Don’T

Table of Contents SEPTEMBER 2000 VOL.5 NO.6 4 Editor’s Notebook A success and a failure? 6 Letters: [email protected] FEATURE FILMS 8 A Conversation With The New Don Bluth After Titan A.E.’s quick demise at the box office and the even quicker demise of Fox’s state-of-the-art animation studio in Phoenix, Larry Lauria speaks with Don Bluth on his future and that of animation’s. 13 Summer’s Sleepers and Keepers Martin “Dr. Toon” Goodman analyzes the summer’s animated releases and relays what we can all learn from their successes and failures. 17 Anime Theatrical Features With the success of such features as Pokemon, are beleaguered U.S. majors going to look for 2000 more Japanese imports? Fred Patten explains the pros and cons by giving a glimpse inside the Japanese film scene. 21 Just the Right Amount of Cheese:The Secrets to Good Live-Action Adaptations of Cartoons Gerard Raiti looks into why some cartoons make successful live-action features while others don’t. Academy Award-winning producer Bruce Cohen helps out. 25 Indie Animated Features:Are They Possible? Amid Amidi discovers the world of producing theatrical-length animation without major studio backing and ponders if the positives outweigh the negatives… Education and Training 29 Pitching Perfect:A Word From Development Everyone knows a great pitch starts with a great series concept, but in addition to that what do executives like to see? Five top executives from major networks give us an idea of what makes them sit up and take notice… 34 Drawing Attention — How to Get Your Work Noticed Janet Ginsburg reveals the subtle timing of when an agent is needed and when an agent might hinder getting that job.