Download but Allow In-App Purchases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ll Be Your Huckleberry

I’ll Be Your Huckleberry It is amazing what will spark a memory. I was transferring a client’s film today and the Christmas scene that appeared on the screen was of a young boy who had just received an inflatable punching bag in the image of Huckleberry Hound. I had one of those. And I certainly remember Hanna-Barbera’s Huckleberry Hound being a favorite cartoon when I was growing up. But my memory played a trick on me. I would have sworn that the Huckleberry Hound Show that I watched as a youngster consisted of three segments: Huckleberry himself; Yogi Bear and Boo-Boo (whose segment eventually became more popular than those of the titular star); and (I thought) Quick Draw McGraw with his sidekick “bing bing bing” Ricochet Rabbit. But I was wrong. Quick Draw had his own show. The third segment for Huck, as he is familiarly known to his young fans, involved a pair of mice, Pixie and Dixie, and the object of their abuse, the cat Mr. Jinx. Just goes to show how memories can tend to distort and blend together over time. A few trivia tidbits about this cartoon from my past: Huckleberry Hound debuted in 1958 and featured a slow moving, slow talking blue dog who held a multitude of jobs and always seemed to succeed due to either luck or an obstinate persistence. Huck was voiced by Daws Butler who also provided the voices for Wally Gator, Yogi Bear, Quick Draw McGraw, and Snagglepuss. Daws Butler fashioned the voice of Yogi Bear after Art Carney’s portrayal of Ed Norton in The Honeymooners. -

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Animation: Types

Animation: Animation is a dynamic medium in which images or objects are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today most animations are made with computer generated (CGI). Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally differ from each other. Apart from short films, feature films, animated gifs and other media dedicated to the display moving images, animation is also heavily used for video games, motion graphics and special effects. The history of animation started long before the development of cinematography. Humans have probably attempted to depict motion as far back as the Paleolithic period. Shadow play and the magic lantern offered popular shows with moving images as the result of manipulation by hand and/or some minor mechanics Computer animation has become popular since toy story (1995), the first feature-length animated film completely made using this technique. Types: Traditional animation (also called cel animation or hand-drawn animation) was the process used for most animated films of the 20th century. The individual frames of a traditionally animated film are photographs of drawings, first drawn on paper. To create the illusion of movement, each drawing differs slightly from the one before it. The animators' drawings are traced or photocopied onto transparent acetate sheets called cels which are filled in with paints in assigned colors or tones on the side opposite the line drawings. The completed character cels are photographed one-by-one against a painted background by rostrum camera onto motion picture film. -

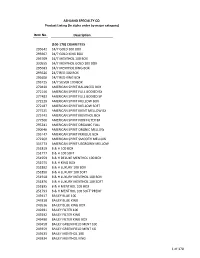

Order Book--7-3-13A.Xlsx

ASHLAND SPECIALTY CO. Product Listing (In alpha order by major category) Item No. Description (100-178) CIGARETTES 295642 24/7 GOLD 100 BOX 295667 24/7 GOLD KING BOX 295709 24/7 MENTHOL 100 BOX 330555 24/7 MENTHOL GOLD 100 BOX 295683 24/7 MENTHOL KING BOX 295626 24/7 RED 100 BOX 295600 24/7 RED KING BOX 295725 24/7 SILVER 100 BOX 279430 AMERICAN SPIRIT BALANCED BOX 272146 AMERICAN SPIRIT FULL BODIED BX 277483 AMERICAN SPIRIT FULL BODIED SP 272229 AMERICAN SPIRIT MELLOW BOX 272187 AMERICAN SPIRIT MELLOW SOFT 277525 AMERICAN SPIRIT MENT MELLOW BX 275743 AMERICAN SPIRIT MENTHOL BOX 277566 AMERICAN SPIRIT NON FILTER BX 293241 AMERICAN SPIRIT ORGANIC FULL 290940 AMERICAN SPIRIT ORGNIC MELLOW 295147 AMERICAN SPIRIT PERIQUE BOX 272260 AMERICAN SPIRIT SMOOTH MELLOW 333773 AMERICAN SPIRIT USGROWN MELLOW 251819 B & H 100 BOX 251777 B & H 100 SOFT 251959 B & H DELUXE MENTHOL 100 BOX 251975 B & H KING BOX 251892 B & H LUXURY 100 BOX 251850 B & H LUXURY 100 SOFT 251918 B & H LUXURY MENTHOL 100 BOX 251876 B & H LUXURY MENTHOL 100 SOFT 251835 B & H MENTHOL 100 BOX 251793 B & H MENTHOL 100 SOFT"PREM" 249417 BAILEY BLUE 100 249318 BAILEY BLUE KING 249516 BAILEY BLUE KING BOX 249391 BAILEY FILTER 100 249292 BAILEY FILTER KING 249490 BAILEY FILTER KING BOX 249458 BAILEY GREEN FIELD MENT 100 249359 BAILEY GREEN FIELD MENT KG 249433 BAILEY MENTHOL 100 249334 BAILEY MENTHOL KING 1 of 170 ASHLAND SPECIALTY CO. Product Listing (In alpha order by major category) Item No. Description 249532 BAILEY MENTHOL KING BOX 249474 BAILEY SKY BLUE 100 249375 BAILEY SKY BLUE -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Tutorial Blogspot Plus Blogger Templates

Tutorial Blogspot Plus Blogger Templates To Bloggers Everywhere 1 2 Contents Contact Us 25 Cara daftar Gmail 25 Cara daftar Blogger pertama kali 27 Cara login ke blogger pertama kali 28 Kontrol panel blogger (dashboard) 29 Cara posting di blogger 30 Halaman Pengaturan (menu dasar) 31 Banyak malware yang ditemukan google 32 Google ! Mesin pembobol yang menakutkan 32 Web Proxy (Anonymous) 33 Daftar alamat google lengkap 34 Google: tampil berdasarkan Link 37 Oom - Pemenang kontes programming VB6 source code 38 (www.planet-sourc... Oom - Keyboard Diagnostic 2002 (VB6 - Open Source) 39 Oom - Access Siemens GSM CellPhone With Full 40 AT+Command (VB6 - Ope... Oom - How to know speed form access (VB6) 40 Para blogger haus akan link blog 41 Nama blog cantik yang disia-siakan dan apakah pantas nama 41 blog dipe... Otomatisasi firewalling IP dan MAC Address dengan bash script 43 Firewalling IP Address dan MAC Address dengan iptables 44 Meminimalis serangan Denial of Service Attacks di Win Y2K/XP 47 Capek banget hari ini.. 48 3 daftar blog ke search engine 48 Etika dan cara promosi blog 49 Tool posting dan edit text blogger 52 Setting Blog : Tab Publikasi 53 Wordpress plugins untuk google adsense 54 Google meluncurkan pemanggilan META tag terbaru 54 “unavailable after” Setting Blog : Tab Format 55 Melacak posisi keyword di Yahoo 56 Mengetahui page ranking dan posisi keyword (kata kunci) anda 56 pada S... Percantik halaman blog programmer dengan "New Code 57 Scrolling Ticke... 20 Terbaik Situs Visual Basic 58 BEST BUY : 11 CD Full Source Code Untuk Programmer 60 Tips memulai blog untuk pemula 62 Lijit: Alternatif search untuk blogger 62 Berpartisipasi dalam Blog "17 Agustus Indonesia MERDEKA" 63 Trafik di blog lumayan, tapi kenapa masih aja minim komentar? 64 Editor posting compose blogger ternyata tidak "wysiwyg" 65 Google anti jual beli link 65 Tips blogger css validator menggunakan "JavaScript Console" 65 pada Fl.. -

HTTP Cookie - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 14/05/2014

HTTP cookie - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 14/05/2014 Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search HTTP cookie From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Navigation A cookie, also known as an HTTP cookie, web cookie, or browser HTTP Main page cookie, is a small piece of data sent from a website and stored in a Persistence · Compression · HTTPS · Contents user's web browser while the user is browsing that website. Every time Request methods Featured content the user loads the website, the browser sends the cookie back to the OPTIONS · GET · HEAD · POST · PUT · Current events server to notify the website of the user's previous activity.[1] Cookies DELETE · TRACE · CONNECT · PATCH · Random article Donate to Wikipedia were designed to be a reliable mechanism for websites to remember Header fields Wikimedia Shop stateful information (such as items in a shopping cart) or to record the Cookie · ETag · Location · HTTP referer · DNT user's browsing activity (including clicking particular buttons, logging in, · X-Forwarded-For · Interaction or recording which pages were visited by the user as far back as months Status codes or years ago). 301 Moved Permanently · 302 Found · Help 303 See Other · 403 Forbidden · About Wikipedia Although cookies cannot carry viruses, and cannot install malware on 404 Not Found · [2] Community portal the host computer, tracking cookies and especially third-party v · t · e · Recent changes tracking cookies are commonly used as ways to compile long-term Contact page records of individuals' browsing histories—a potential privacy concern that prompted European[3] and U.S. -

From Moments to Minutes Advertising with Social Play.Pdf

5 From Moments to Minutes Advertising with Social Play Virtual worlds are a rapidly growing social-media platform, and this is particularly true for kids. Thought of by many as 3D renditions of 2D social networks, virtual worlds supply many desirable features for the youth market still unavailable in the realm of social networks. Among these are a sense of immediacy, unparalleled media richness, and the heightened interactivity possible in the virtual space. Young consumers respond to the immediacy of communications, meaning that communica- tions occur in real time (while social networks still primarily provide asynchronous response). Real-time response adds to the sense of contact comfort participants feel. Media richness is embellished with the enhanced visual representations of virtual worlds as well as the ability to chat using instant messenger, electronic mail, and sometimes voice chat features. Lastly, social networks like MySpace are limited in what can be offered for participants in terms of entertaining and interactive pursuits within the space. It is no wonder then that young consumers are enam- ored with virtual worlds. eMarketer estimates that 24% of the 34.3 million child and teen Internet users in the United States used virtual worlds on at least a monthly basis in 2007 and this figure is expected to rise rapidly over the short term.1 76 Advertising 2.0 For marketers, social virtual worlds represent an enormous opportu- nity for branding by extending the time consumers spend with a brand’s message from moments to minutes. Indeed, the average amount of time spent per session in social virtual worlds ranges from as little as twenty minutes to more than two hours—substantially more than the typical thirty seconds of attention garnered by a television commercial. -

Teachers Guide

Teachers Guide Exhibit partially funded by: and 2006 Cartoon Network. All rights reserved. TEACHERS GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE 3 EXHIBIT OVERVIEW 4 CORRELATION TO EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS 9 EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS CHARTS 11 EXHIBIT EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES 13 BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR TEACHERS 15 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS 23 CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES • BUILD YOUR OWN ZOETROPE 26 • PLAN OF ACTION 33 • SEEING SPOTS 36 • FOOLING THE BRAIN 43 ACTIVE LEARNING LOG • WITH ANSWERS 51 • WITHOUT ANSWERS 55 GLOSSARY 58 BIBLIOGRAPHY 59 This guide was developed at OMSI in conjunction with Animation, an OMSI exhibit. 2006 Oregon Museum of Science and Industry Animation was developed by the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry in collaboration with Cartoon Network and partially funded by The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. and 2006 Cartoon Network. All rights reserved. Animation Teachers Guide 2 © OMSI 2006 HOW TO USE THIS TEACHER’S GUIDE The Teacher’s Guide to Animation has been written for teachers bringing students to see the Animation exhibit. These materials have been developed as a resource for the educator to use in the classroom before and after the museum visit, and to enhance the visit itself. There is background information, several classroom activities, and the Active Learning Log – an open-ended worksheet students can fill out while exploring the exhibit. Animation web site: The exhibit website, www.omsi.edu/visit/featured/animationsite/index.cfm, features the Animation Teacher’s Guide, online activities, and additional resources. Animation Teachers Guide 3 © OMSI 2006 EXHIBIT OVERVIEW Animation is a 6,000 square-foot, highly interactive traveling exhibition that brings together art, math, science and technology by exploring the exciting world of animation. -

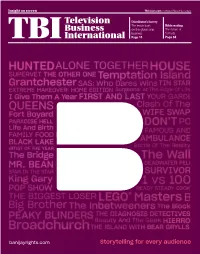

Pofc TBI Main Octnov20.Indd

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | October/November 2020 Distributor's Survey The inside track Bible reading on the global sales The future of business formats Page 14 Page 34 pOFC TBI Main OctNov20.indd 1 02/10/2020 15:28 pIFC-01 Global Agency TBI OctNov20.indd 2 01/10/2020 10:35 pIFC-01 Global Agency TBI OctNov20.indd 3 01/10/2020 10:35 ABANDONED ENGINEERING S5 12 x 60’ Like a Shot Entertainment EDGES UNKNOWN RACE TO VICTORY 7 x 60’ 4East Media 6 x 60’ CIC Media SEX UNLIMITED 5 x 60’ Barcroft Studios For sales enquiries please contact: [email protected] www.beyondrights.tv pXX Beyond TBI OctNov20.indd 1 28/09/2020 09:44 Welcome | This issue Contents TBI October/November 2020 34. Future-proofi ng formats With the pandemic upending the TV industry across the world, Mark Layton fi nds out what the impact has been on the global format sales business and how it has adapted to the new normal. 38. Keeping the music playing through Covid Karen Smith, MD of Tuesday’s Child and Tuesday’s Child Scotland, on The Hit List. 10 40. Formats Hot Picks The formats that caught our eye this month including 9 Windows, Pooch Perfect and Tough As Nails. 10. Press record TikTok has exploded into the public consciousness like few – if 42. e colourful world of co-productions any other – video-led service before it. UK & Europe chief Rich Sharing production costs on unscripted projects was on the increase Waterworth tells Richard Middleton how he sees the future prior to Covid-19, but is the pandemic accelerating this further? Tim panning out. -

Wendy's® Expands Partnership with Adult Swim on Hit Series Rick and Morty

NEWS RELEASE Wendy's® Expands Partnership With Adult Swim On Hit Series Rick And Morty 6/15/2021 Fans Can Enjoy New Custom Coca-Cola Freestyle Mixes and Free Wendy's Delivery to Celebrate Global Rick and Morty Day on Sunday, June 20 DUBLIN, Ohio, June 15, 2021 /PRNewswire/ -- Wubba Lubba Grub Grub! Wendy's® and Adult Swim's Rick and Morty are back at it again. Today they announced year two of a wide-ranging partnership tied to the Emmy ® Award-winning hit series' fth season, premiering this Sunday, June 20. Signature elements of this season's promotion include two new show themed mixes in more than 5,000 Coca-Cola Freestyle machines in Wendy's locations across the country, free Wendy's in-app delivery and a restaurant pop-up in Los Angeles with a custom fan drive-thru experience. "Wendy's is such a great partner, we had to continue our cosmic journey with them," said Tricia Melton, CMO of Warner Bros. Global Kids, Young Adults and Classics. "Thanks to them and Coca-Cola, fans can celebrate Rick and Morty Day with a Portal Time Lemon Lime in one hand and a BerryJerryboree in the other. And to quote the wise Rick Sanchez from season 4, we looked right into the bleeding jaws of capitalism and said, yes daddy please." "We're big fans of Rick and Morty and continuing another season with our partnership with entertainment 1 powerhouse Adult Swim," said Carl Loredo, Chief Marketing Ocer for the Wendy's Company. "We love nding authentic ways to connect with this passionate fanbase and are excited to extend the Rick and Morty experience into our menu, incredible content and great delivery deals all season long." Thanks to the innovative team at Coca-Cola, fans will be able to sip on two new avor mixes created especially for the series starting on Wednesday, June 16 at more than 5,000 Wendy's locations through August 22, the date of the Rick and Morty season ve nale.