The Ballets Russes and the Orient in the Modern Western Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elect Your Council

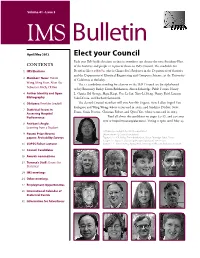

Volume 41 • Issue 3 IMS Bulletin April/May 2012 Elect your Council Each year IMS holds elections so that its members can choose the next President-Elect CONTENTS of the Institute and people to represent them on IMS Council. The candidate for 1 IMS Elections President-Elect is Bin Yu, who is Chancellor’s Professor in the Department of Statistics and the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, at the University 2 Members’ News: Huixia of California at Berkeley. Wang, Ming Yuan, Allan Sly, The 12 candidates standing for election to the IMS Council are (in alphabetical Sebastien Roch, CR Rao order) Rosemary Bailey, Erwin Bolthausen, Alison Etheridge, Pablo Ferrari, Nancy 4 Author Identity and Open L. Garcia, Ed George, Haya Kaspi, Yves Le Jan, Xiao-Li Meng, Nancy Reid, Laurent Bibliography Saloff-Coste, and Richard Samworth. 6 Obituary: Franklin Graybill The elected Council members will join Arnoldo Frigessi, Steve Lalley, Ingrid Van Keilegom and Wing Wong, whose terms end in 2013; and Sandrine Dudoit, Steve 7 Statistical Issues in Assessing Hospital Evans, Sonia Petrone, Christian Robert and Qiwei Yao, whose terms end in 2014. Performance Read all about the candidates on pages 12–17, and cast your vote at http://imstat.org/elections/. Voting is open until May 29. 8 Anirban’s Angle: Learning from a Student Left: Bin Yu, candidate for IMS President-Elect. 9 Parzen Prize; Recent Below are the 12 Council candidates. papers: Probability Surveys Top row, l–r: R.A. Bailey, Erwin Bolthausen, Alison Etheridge, Pablo Ferrari Middle, l–r: Nancy L. Garcia, Ed George, Haya Kaspi, Yves Le Jan 11 COPSS Fisher Lecturer Bottom, l–r: Xiao-Li Meng, Nancy Reid, Laurent Saloff-Coste, Richard Samworth 12 Council Candidates 18 Awards nominations 19 Terence’s Stuff: Oscars for Statistics? 20 IMS meetings 24 Other meetings 27 Employment Opportunities 28 International Calendar of Statistical Events 31 Information for Advertisers IMS Bulletin 2 . -

1 Hollywood Misfits. Marilyn Monroe E Ben Hecht Sarebbe Curioso Se

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Institutional Research Information System University of Turin 1 Hollywood Misfits. Marilyn Monroe e Ben Hecht Sarebbe curioso se risultasse che sono un’autrice. Anita Loos, Gli uomini preferiscono le bionde. Ben Hecht, uno degli sceneggiatori più importanti e prolifici della storia del cinema americano classico, tra le tante cose che ha fatto nella sua poliedrica carriera, è stato anche ghostwriter di Marilyn Monroe, per un progetto abortito di autobiografia, intitolata My Story, che avrebbe trovato un esito editoriale solo nel 1974, dopo che sia la diva sia lo scrittore erano ormai morti da tempo (Hecht scompare poco meno di due anni dopo Marilyn, nell’aprile del 1964). In questa sede, intendo, da un lato, ricostruire la complessa vicenda della redazione e della pubblicazione del libro, uno «highly problematic text», lo definisce giustamente Sarah Churchwell nel suo The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe1, basandomi sui documenti che ho esaminato alla Newberry Library di Chicago, dove sono conservati i “Ben Hecht Papers”2. Dall’altro lato, proverò a ragionare sul contenuto di My Story, inteso sia come opera di/su Marilyn Monroe, sia in quanto opera “di” Hecht. Per molti versi, My Story è il libro “onesto e feroce” su Hollywood che Hecht avrebbe potuto scrivere e che non scrisse mai, quanto meno non con il suo nome in copertina. Quando esce per la prima volta, su iniziativa di Milton Greene (fotografo e amico dell’attrice), My Story è a firma unicamente della Monroe. Solo con la riedizione del 2007, per i tipi di Taylor Trade, viene riconosciuto l’apporto dello sceneggiatore (questa volta, l’opera è attribuita a: «Marilyn Monroe with Ben Hecht»). -

A'level Dance Knowledge Organiser Christopher

A’LEVEL DANCE KNOWLEDGE ORGANISER CHRISTOPHER BRUCE Training and background Influences • Christopher Bruce's interest in varied forms of • Walter Gore: Bruce briefly performed with Walter Gore’s company, London Ballet, in 1963, whilst a student at the Ballet choreography developed early in his career from his own Rambert School in London. Gore was a pupil of Massine and Marie Rambert in the 1930s before becoming one of Ballet exposure to classical, contemporary and popular dance. Rambert’s earliest significant classical choreographers. His influence on Bruce is seen less in classical technique and more in the • Bruce's father who introduced him to dance, believing it abstract presentation of social and psychological realism. This can of course be a characteristic of Rambert Ballet’s ‘house could provide a useful career and would help strengthen style’, post-1966. his legs, damaged by polio. • His early training, at the Benson Stage Academy, • Norman Morrice: As Associate Artistic Director of Ballet Rambert in 1966, Morrice was interested in exploring contemporary Scarborough, included ballet, tap and acrobatic dancing - themes and social comment. He was responsible for the company’s change in direction to a modern dance company as he all elements which have emerged in his choreography. introduced Graham technique to be taught alongside ballet. • At the age of thirteen he attended the Ballet Rambert School and Rambert has provided the most consistent • Glen Tetley: Glen Tetley drew on balletic and Graham vocabulary in his pieces, teaching Bruce that ‘the motive for the umbrella for his work since. movement comes from the centre of the body … from this base we use classical ballet as an extension to give wider range and • After a brief spell with Walter Gore's London Ballet, he variety of movement’. -

NEWSLETTER No

NEWSLETTER No. 464 December 2016 ATHENA PRIZE The London Mathematical Society Women in Diversity Conference on 31 October 2016. The Mathematics Committee was presented with medal was presented by Dr Julie Maxton, the inaugural Royal Society Athena Prize (see Executive Director, Royal Society. See page 3 for November LMS Newsletter) at the Royal Society images of the medal. Dr Julie Maxton, Executive Director, Royal Society; Professor John Greenlees, LMS Vice President; Dr Cathy Hobbs; Professor Gwyneth Stallard; Dr Eugenie Hunsicker, Chair, Women in Mathematics Committee SOCIETY MEETINGS AND EVENTS • 16–17 December: Prospects in Mathematics • 5 May 2017: Mary Cartwright Lecture, London Meeting, York page 16 • 1 June 2017: Northern Regional Meeting, York • 20 December: SW & South Wales Regional • 30 June 2017: Graduate Student Meeting, Bath page 15 Meeting, London • 18–22 April 2017: LMS Invited Lectures, Newcastle page 24 • 30 June 2017: Society Meeting, London NEWSLETTER ONLINE: newsletter.lms.ac.uk @LondMathSoc LMS NEWSLETTER http://newsletter.lms.ac.uk Contents No. 464 December 2016 7 18 Calendar of Events 39 British Combinatorial Conference.........21 British Postgraduate Model LMS Items Theory Conference...............................20 Athena Prize............................................1 2 Young Theorists’ Forum..........................21 Caring Supplementary Grants................5 Cecil King Travel Scholarship News 2017 – call for nominations................25 Chern Medal 2018...................................4 Council Diary............................................6 -

Life in a Postcard Online

GMu9d (Read free) Life In A Postcard Online [GMu9d.ebook] Life In A Postcard Pdf Free Rosemary Bailey ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1946621 in eBooks 2013-04-29 2013-04-29File Name: B00BY7NJMY | File size: 68.Mb Rosemary Bailey : Life In A Postcard before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Life In A Postcard: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Once upon a monastery: "Time traveling" in FranceBy The Bronte SistersI was charmed by this book. Author Bailey has a gift for drawing the reader in, from the opening pages, as she shares her experience (along with that of her husband and young son)of moving into a medieval monastery--in need of vast repair--in the south of France. Whether one is looking to buy a home in Europe, an enthusiast for all things French, or an armchair traveler game for a good trip, LIFE IN A POSTCARD opens a rich and memorable excursion. It's an excursion described with zest, frankness,love of language,humility, and welcome humor.3 of 4 people found the following review helpful. DisappointingBy A CustomerAfter reading many books about French Provence. I tried to find books about other parts of France so I bought this book. However, Ms. Bailey's limited French resulted in her life in the French Pyrenees mostly among the expat. To the end of the book, I still did not feel or learn something much about the French Pyrenees. -

Complete Film Noir

COMPLETE FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1965) Page 1 of 18 CONSENSUS FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1959) (1960-1965) dThe idea for a COMPLETE FILM NOIR LIST came to me when I realized that I was “wearing out” a then recently purchased copy of the Film Noir Encyclopedia, 3rd edition. My initial plan was to make just a list of the titles listed in this reference so I could better plan my film noir viewing on AMC (American Movie Classics). Realizing that this plan was going to take some keyboard time, I thought of doing a search on the Internet Movie DataBase (here after referred to as the IMDB). By using the extended search with selected criteria, I could produce a list for importing to a text editor. Since that initial list was compiled almost twenty years ago, I have added additional reference sources, marked titles released on NTSC laserdisc and NTSC Region 1 DVD formats. When a close friend complained about the length of the list as it passed 600 titles, the idea of producing a subset list of CONSENSUS FILM NOIR was born. Several years ago, a DVD producer wrote me as follows: “I'd caution you not to put too much faith in the film noir guides, since it's not as if there's some Film Noir Licensing Board that reviews films and hands out Certificates of Authenticity. The authors of those books are just people, limited by their own knowledge of and access to films for review, so guidebooks on noir are naturally weighted towards the more readily available studio pictures, like Double Indemnity or Kiss Me Deadly or The Big Sleep, since the many low-budget B noirs from indie producers or overseas have mostly fallen into obscurity.” There is truth in what the producer says, but if writers of (film noir) guides haven’t seen the films, what chance does an ordinary enthusiast have. -

(PDF) Dk Eyewitness Travel Guide

(PDF) Dk Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris Dk Publishing, Alan Tillier, Ian O'Leary, Rosemary Bailey, Draughtsman Ltd, Delphine Lawrance, Katherine Spenley - book pdf free PDF DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris Full Collection, Read Online DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris E-Books, DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris Ebooks, DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris Book Download, Read Online DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris E-Books, Read Online DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris E-Books, DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris PDF, by DK Publishing, Alan Tillier, Ian O'Leary, Rosemary Bailey, Draughtsman Ltd, Delphine Lawrance, Katherine Spenley pdf DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris, DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris Ebook Download, online pdf DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris, Read Online DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris E-Books, Download Free DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris Book, DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris PDF Download, DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris Ebooks Free, DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris Free Download, Free Download DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris Ebooks DK Publishing, Alan Tillier, Ian O'Leary, Rosemary Bailey, Draughtsman Ltd, Delphine Lawrance, Katherine Spenley, Read Best Book Online DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris, Download DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris Online Free, pdf download DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris, Download Online DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Paris Book, CLICK TO DOWNLOAD kindle, epub, azw, mobi Description: The key to understanding why someone on Reddit decides it's OK for some other blog about my personal -

Chapter 9 Ballet Edited.Ppt.Pdf

C H A P T E R 9 Ballet Chapter ?? Chapter 9 Ballet Enduring understanding: Ballet is a classic, Western dance genre and a performing art. Essential question: How does ballet help me express myself as a dancer? Learning Objectives •Recognize major ballet works, styles, and ballet artists in history. •Execute basic ballet technique, use ballet vocabulary, and perform barre exercises and center combinations. •Apply ballet etiquette and dance safety while dancing. •Evaluate and respond to classical and contemporary ballet performances. Introduction Ballet began as a Western classical dance genre 400 years ago and has evolved into an international performing art form. The word ballet comes from the Italian term ballare, meaning to dance. Chapter 9 Vocabulary Terms adagio allegro à la seconde à terre ballet ballet technique barre center derrière stage directions Devant turnout en l’air Ballet Beginnings Ballet moved from Italy to France when Catherine de’ Medici married the heir to the French throne, King Henry II. She produced what has become known as the first ballet, La Comique de la Reine, in 1588. Ballet at the French Court Louis XIV performed as a dancer and gained the title The Sun King after one of his most famous dancing roles. A patron of the arts, Louis XIV established the Academy of Music and Dance. In the next century the Academy would become the Paris Opéra. Court Ballets • During the 17th century, court ballets were dance interludes between dramatic or vocal performances or entire performances. • Sometimes ballets were part of themed balls such as pastoral or masquerade balls. -

The Problems of Studying the Ballet in the Culture of the Late XIX - Early XX Centuries

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 5, Issue 9, September 2018, PP 11- 15 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0509002 www.arcjournals.org The Problems of Studying the Ballet in the Culture of the Late XIX - Early XX Centuries Тatiana Portnova Doctor of Art History, Professor of Choreography Art department of Slavic Culture Institute, Professor of Art History Department of A. Kosygin Russian State University *Corresponding Author: Тatiana Portnova, Doctor of Art History, Professor of Choreography Art department of Slavic Culture Institute, Professor of Art History Department of A. Kosygin Russian State University Abstract: The article reveals the role of the Russian ballet in the cultural pattern at the turn of the 20th century. Purpose of the article is to determine the direction of development of interaction between national choreography and artistic and imaginative interpretation of its synthetic whole against a background of complex and ambiguous processes taking course at critical stages of the Russian culture, based at the existing visual materials of archive and museum funds. An aspect of art review was selected, allowing consideration of the diverse options of synthesis of ballet and plastic arts. The attraction of the visual arts to “balletness” and the tendency of Russian choreography to rely on images of painting, graphics and sculpture characteristic to the turn of the century are two sides of the single process. In this context, the Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company, being saturated with expressive plastic spectacular imagery, served as the bright frame for the last stage of the Russian Silver Age. -

![Lucy Kroll Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3113/lucy-kroll-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-2283113.webp)

Lucy Kroll Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Lucy Kroll Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2002 Revised 2010 April Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms006016 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm82078576 Prepared by Donna Ellis with the assistance of Loren Bledsoe, Joseph K. Brooks, Joanna C. Dubus, Melinda K. Friend, Alys Glaze, Harry G. Heiss, Laura J. Kells, Sherralyn McCoy, Brian McGuire, John R. Monagle, Daniel Oleksiw, Kathryn M. Sukites, Lena H. Wiley, and Chanté R. Wilson Collection Summary Title: Lucy Kroll Papers Span Dates: 1908-1998 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1950-1990) ID No.: MSS78576 Creator: Kroll, Lucy Extent: 308,350 items ; 881 containers plus 15 oversize ; 356 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Literary and talent agent. Contracts, correspondence, financial records, notes, photographs, printed matter, and scripts relating to the Lucy Kroll Agency which managed the careers of numerous clients in the literary and entertainment fields. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Braithwaite, E. R. (Edward Ricardo) Davis, Ossie. Dee, Ruby. Donehue, Vincent J., -1966. Fields, Dorothy, 1905-1974. Foote, Horton. Gish, Lillian, 1893-1993. Glass, Joanna M. Graham, Martha. Hagen, Uta, 1919-2004. -

DOCTORAL THESIS the Dancer's Contribution: Performing Plotless

DOCTORAL THESIS The Dancer's Contribution: Performing Plotless Choreography in the Leotard Ballets of George Balanchine and William Forsythe Tomic-Vajagic, Tamara Award date: 2013 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 THE DANCER’S CONTRIBUTION: PERFORMING PLOTLESS CHOREOGRAPHY IN THE LEOTARD BALLETS OF GEORGE BALANCHINE AND WILLIAM FORSYTHE BY TAMARA TOMIC-VAJAGIC A THESIS IS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF DANCE UNIVERSITY OF ROEHAMPTON 2012 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the contributions of dancers in performances of selected roles in the ballet repertoires of George Balanchine and William Forsythe. The research focuses on “leotard ballets”, which are viewed as a distinct sub-genre of plotless dance. The investigation centres on four paradigmatic ballets: Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments (1951/1946) and Agon (1957); Forsythe’s Steptext (1985) and the second detail (1991). -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room.