The Reception of Dynasty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luis Venegas What to Read, Watch, Listen To, and Know About to Become a Bullet-Proof Style Expert

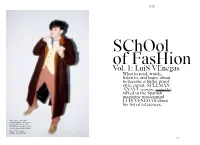

KUltur kriTik SChOol of FasHion Vol. 1: LuiS VEnegas What to read, watch, listen to, and know about to become a bullet-proof style expert. SULEMAN ANAYA (username: vertiz136) talked to the Spanish magazine mastermind LUIS VENEGAS about his list of references. coat, jacket, and pants: Lanvin Homme, waistcoat: Polo Ralph Lauren, shirt: Dior Homme, bow tie: Marc Jacobs, shoes: Pierre Hardy photo: Chus Antón, styling: Ana Murillas 195 KUltur SChOol kriTik of FasHion At 31, Luis Venegas is already a one-man editorial powerhouse. He produces and publishes three magazines that, though they have small print runs, have a near-religious following: the six-year-old Fanzine 137 – a compendium of everything Venegas cares about, Electric Youth (EY!) Magateen – an oversized cornucopia of adolescent boyflesh started in 2008, and the high- ly lauded Candy – the first truly queer fashion magazine on the planet, which was launched last year. His all-encompassing, erudite view of the fashion universe is the foundation for Venegas’ next big project: the fashion academy he plans to start in 2011. It will be a place where people, as he says, “who are interested in fashion learn about certain key moments from history, film and pop culture.” To get a preview of the curriculum at Professor Venegas’ School of Fashion, Suleman Anaya paid Venegas a visit at his apartment in the Madrid neighborhood of Malasaña, a wonderful space that overflows with the collected objects of his boundless curiosity. Television ● Dynasty ● Dallas What are you watching these days in your scarce spare time? I am in the middle of a Dynasty marathon. -

2018 Annual Report

Annual Report 2018 Dear Friends, welcome anyone, whether they have worked in performing arts and In 2018, The Actors Fund entertainment or not, who may need our world-class short-stay helped 17,352 people Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund is here for rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational and speech)—all with everyone in performing arts and entertainment throughout their the goal of a safe return home after a hospital stay (p. 14). nationally. lives and careers, and especially at times of great distress. Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, Our programs and services Last year overall we provided $1,970,360 in emergency financial stronger than ever and is here for those who need us most. Our offer social and health services, work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as ANNUAL REPORT assistance for crucial needs such as preventing evictions and employment and training the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. paying for essential medications. We were devastated to see programs, emergency financial the destruction and loss of life caused by last year’s wildfires in assistance, affordable housing, 2018 California—the most deadly in history, and nearly $134,000 went In addition, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS continues to be our and more. to those in our community affected by the fires and other natural steadfast partner, assuring help is there in these uncertain times. disasters (p. 7). Your support is part of a grand tradition of caring for our entertainment and performing arts community. Thank you Mission As a national organization, we’re building awareness of how our CENTS OF for helping to assure that the show will go on, and on. -

Homecoming Court Announced Mccormick 470 Voters Didn't Sound Bad Compared with Other Elections

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The Parthenon University Archives 10-27-1994 The Parthenon, October 27, 1994 Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Marshall University, "The Parthenon, October 27, 1994" (1994). The Parthenon. 3306. https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/3306 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Parthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Oct. 27, 1994 MARSHALL UNIVERSITY Thursday Mostly sunny High in upper 50s • VOTING Homecoming Court announced McCormick 470 voters didn't sound bad compared with other elections By Jason Philyaw is Lynn "I think it College of Business senator. Reporter Celdran, a is great to be The senior representative Huntington able to rep and Ms. Marshall will be an Students who voted. for graduate stu .resent Mar nounced at halftime at Homecoming Court this week dent, who has shall Uni- Saturday's football game did not have the chance to vote a master of versity," against The Citadel. for Mr. Marshall There was no arts degree in Phillips Running for the Homecom need. teaching. said. ing Queen are Kristin Butcher, There were no freshman and Stephanie Mr.~/ "There a Huntington broadcast jour sophomore male applicants and Hayhurst, DtMl!Plti/U,1 were actu nalism major, and Penny only one from both the junior Pennsboro ally two Copen, an Elizabeth public re and senior classes. -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

New on Video &

New On Video & DVD Yes Man Jim Carrey returns to hilarious form with this romantic comedy in the same vein as the Carrey classic Liar Liar. After a few stints in more serious features like Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind and The Number 23, Carrey seems right at home playing Carl, a divorcé who starts out the film depressed and withdrawn, scared of taking a risk. Pressured by his best friend, Peter (Bradley Cooper), to get his act together or be stuck with a lonely life, Carl attends a New Age self-help seminar intended to change "no men" like Carl into "yes men" willing to meet life's challenges with gusto. Carl is reluctant at first, but finds the seminar to be ultimately life-changing when he's coerced into giving the "say yes" attitude a try. As the first opportunity to say yes presents itself, Carl hesitantly utters the three-letter word, setting the stage for a domino effect of good rewards, and giving Carrey a platform to show off his comic chops. But over time Carl realizes that saying yes to everything indiscriminately can reap results as complicated and messy as his life had become when saying "no" was his norm. The always-quirky Zooey Deschanel adds her signature charm as Carl's love interest, Allison. An unlikely match at first glance, the pair actually develop great chemistry as the story progresses, the actors play- ing off each other's different styles of humor. Rhys Darby also shines as Carl's loveable but clueless boss, and That 70s Show's Danny Masterson appears as another one of Carl's friends. -

Z Archeologii Mediów : "Dynastia" I "Koło Fortuny"

Telewizja buduje kapitalizm Mateusz Halawa Z ARCHEOLOGII MEDIÓW: DYNASTIA I KOŁO FORTUNY Dla Alexis Guzik z Małogoszczy, która ma już dziesięć lat. ilm zaczyna się widokiem ziemi z kosmosu i towarzyszącą mu kakofonią dźwięków komunika tów radiowych i telewizyjnych (wy)emitowanych przez ludzi w przestrzeń1. Im szerszy staje się kadr i im bardziej widz oddala się od Ziemi, tym starsze komunikaty słychać: zabójstwo najpierw F Roberta, później Johna Kennedy'ego, później zaś relacje z drugiej wojny światowej. Jak na archeologicznym wykopalisku: im starsza skorupa, tym głębiej (dalej) ją znajdujemy. Bohaterka, Eleanor Arroway, grana przez Jodie Foster, pracuje w programie poszukiwań cywilizacji pozaziemskiej (SETI). Pewnego dnia udaje jej się odebrać tajemniczy sygnał, który po zdekodowaniu okazuje się być przekazem telewizyjnym: przemówie niem Hitlera na otwarciu olimpiady w Berlinie w 1936 r. To pierwszy nadany przez ludzi przekaz, który zna lazł się w przestrzeni kosmicznej - zauważa Eleanor. Ktoś go usłyszał (pozaziemska cywilizacja?) i odesłał z powrotem zszokowanym naukowcom. To filmowy obraz archeologii obrazu telewizyjnego i fal dźwiękowych i wizja aktualizowania dawnego przekazu medialnego we współczesności. W przybliżeniu oddaje to, czym chcę się tu zająć. (Nawet z naj gorszej książki można się czegoś nauczyć, miał powiedzieć Pliniusz Starszy - zasada ta odnosi się również do kiepskich filmów science fiction). „Nośnikiem pamięci o przeszłości, przynajmniej potencjalnym - pisze historyk Marcin Kula - jest do słownie wszystko” (Kula, 2002: 7-8). W książce Nośniki pamięci historycznej badacz, zajmując się czę sto faktami i rzeczami pozornie pozbawionymi historycznego znaczenia, pokazuje, jak można rekonstru ować przeszłość z drobnych fragmentów tego, co pozostało. Próbuje też przewidzieć, co pozostanie z naszych czasów. -

Emmanuel Basi(Eteers Shine

VOLUME 3 NUMBER 4 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS FEBRUARY, 1951 EMMANUEL BASI(ETEERS SHINE Meet Some Emmanuel Seniors Sodality Plans Sports Interest Grows at Emmanuel The following students have been chosen to represent One of the many activities introduced this year at Em their particular fields for their outstanding academic s uc Lent manuel College is intercollegiate basketball. The efforts and cess. Sodality plans for Lent at Em- skill of player-coach Polly Neelon, Senior, have resulted in a NORMA HALLIDAY - English manuel, center about active par- s mooth-working team which has competed with some of the A wedding in June will initiate Norma's ticipation by the entire student best collegiate teams in New England. The managerial duties life after graduation. She doesn't plan on body in the work of the Con- have been assumed and capably handled by Rosemary Sei- leaving her English major behind, however, fraternity of Christian Doctrine_ for she hopes to find time for creative writing In this regard Reverend Albert __________bert, Sophomore._ Emmanuel has showed herself as well as book reviews for the town paper. W. Low was present at the stu to be a growing threat in com· Her hobbies during her four years of college dent assembly and later in the Notre Dame petition with Baroness Possa have very conveniently centered around cook- chapel on Monday, F ebruary 12 School of Physical Education, ing. She is marrying Charles Frippc and to tell students about the activi Novices Boston University, Boston Col· they will live in Winthrop. ties of the Confraternity and to lege School of Nursing, Rivier enroll t~1techists who will teach On February second, the College (Nashua, New Hamp in the Mission Church parish. -

Nancy Malone Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8hq420r No online items Nancy Malone papers, ca. 1946-2000s Finding aid prepared by Liz Graney and Sue Hwang assisted by Julie Graham; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2014 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Nancy Malone papers, ca. PASC 254 1 1946-2000s Title: Nancy Malone papers Collection number: PASC 254 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 35.0 linear ft.(62 boxes, 2 record cartons, and 4 flat boxes) Date (inclusive): ca. 1946-2000 Abstract: Nancy Malone began her career at the age of six, modeling and appearing on live radio and television programs. She went on to become an accomplished actor, director and producer and was a co-founder of Women in Film, the nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting women's roles within the entertainment industry. The collection consists of material representing Malones' involvement in various projects as actress, director and producer, her association with Women in Film, her contributions to the advancement of the entertainment community and her various achievements outside of the industry. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Creator: Malone, Nancy Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. -

Se Opp for Glamour, Intriger Og Legendariske Catfights: Nå Er Dynastiet Tilgjengelig På Viafree

Familien samlet. F.v: Sammy Jo Carrington, Claudia Blaisdel Carrington, Blake Carrington Krystle Carrington, Alexis Carrington og Fallon Carrington Colby. 20-03-2018 14:18 CET Se opp for glamour, intriger og legendariske catfights: Nå er Dynastiet tilgjengelig på Viafree. Tidenes mest ikoniske såpeoperaer har inntatt Viafree. Nå kan du fråtse i elleville intriger og herlig galskap i seriene Glamour, I gode og onde dager, og siste tilskudd på såpestammen, Dynastiet. Da Dynastiet ble sendt på TV på 80-tallet var det folketomme gater og folk satt klistret til skjermen for å få med seg feiden mellom de to steinrike familiene Carrington og Colby, og ikke minst de legendariske catfightene mellom sjefshurpa Alexis og den skinnhellige Krystle. Nå kan skandalene, de skyhøye skulderputene, det voluminøse håret, utroskapen og de ulidelige cliffhangerne gjenoppleves. Hver dag blir nye episoder av alle de tre seriene tilgjengelige for strømming på Viafree - helt gratis. Påsken er med andre ord reddet, og det er ingen grunn til å bli Blake om nebbet. Se innebygd innhold her Nordic Entertainment Group (NENT Group) er Nordens ledende underholdningsleverandør. Vi underholder millioner av mennesker hver dag med våre strømmetjenester, TV-kanaler og radiostasjoner, og våre produksjonsselskaper skaper nytt og spennende innhold for medieselskaper i hele verden. Vi gjør livet mer underholdende ved å tilby de beste og mest varierte opplevelsene – fra direktesendt radio og sport, til filmer, serier, musikk og egenproduserte programmer. Med hovedkvarter i Stockholm er NENT Group en del av Modern Times Group MTG AB, et ledende internasjonalt digitalt underholdningskonsern som er notert på Nasdaq Stockholm (‘MTGA’ og ‘MTGB’). -

Mike… Still Fabulous at 40 by Karla Karanza

DECEMBER 2012 Mike… Still Fabulous at 40 By Karla Karanza If you’re ever looking for Mr. Klausman Now, the guy is the CBS Senior Vice and he’s not in his offi ce, go to the 2nd fl oor President of West Coast Operations and balcony on Mack Sennett. Outside at the President of CBS Studio Center. That’s one table by the stairs, Mike conducts business motivated young man. as usual. A strong, determined business man, a devoted family man, and one of the best bosses in this town, Mike Klausman knows what it means to work. 40 years ago, Mike was an usher over at TV City while studying biology (yes, he was planning on being a doctor) at CSUN. There’s no job at this lot Mike won’t take on. Mike oversees more than Young Mike Klausman and his beautiful bride, 3,000 employees between the Beckie, on The Newlywed Game two facilities and sometimes He worked his way up the ranks through it seems like he knows every the video library, various production one of their names. He support jobs and eventually became can deal with television RIGHTS RESERVED. ALL Lipson/CBS ©2009 CBS BROADCASTING INC. Photo: Cliff Director of Program Production Services. executives as easily as 20 years ago, he became Vice President and he deals with the technical professionals, Homeless Committee of the Entertainment General Manager of CBS/MTM Studios and knows everything that’s going on with the Industry Foundation, and the Olive Crest one short year after that, he was promoted business fi nancials and marketing, as well Home and Services for Abused Children. -

Joint Meeting Jpa Executive Committee & Cvb Board Of

JPA-CVB Board of Directors Joint Meeting Friday, May 17, 2019 Page 1 JOINT MEETING JPA EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE & CVB BOARD OF DIRECTORS MINUTES Call to Order Meeting was called to order at 8:15 a.m. by Linda Evans, JPA Chair and Mayor of the City of La Quinta, at the Renaissance Indian Wells Resort & Spa, Esmeralda 1-3, in Indian Wells, CA. Roll Call The roll call is recorded on the following page. MAY 17, 2019 JPA-CVB Board of Directors Joint Meeting Friday, May 17, 2019 Page 1 JOINT POWERS AUTHORITY Location: Renaissance Indian Wells Resort & Spa 44400 Indian Wells Lane Linda Evans, Chair City of La Quinta Indian Wells, CA 92210 Geoff Kors, Vice Chair City of Palm Springs Regular Meeting Friday, May 17, 2019, 8:00am – 10:00am Ernesto Gutierrez City of Cathedral City Gary Gardner JPA ROLL CALL | PRESENT PRESENT NOT/YTD City of Desert Hot Springs Richard Balocco Linda Evans, Mayor, Chair X City of Indian Wells CITY OF LA QUINTA Elaine Holmes Robert Radi, Council Member City of Indio Jan Harnik Geoff Kors, Council Member, Vice Chair X City of Palm Desert CITY OF PALM SPRINGS Charles Townsend City of Rancho Mirage Robert Moon, Mayor V. Manuel Perez County of Riverside Ernesto Gutierrez, Council Member X CITY OF CATHEDRAL CITY CVB BOARD OF Mark Carnevale, Mayor Pro Tem DIRECTORS Tom Tabler, Chairman Gary Gardner, Council Member X J.W. Marriott Desert Springs CITY OF DESERT HOT SPRINGS Resort & Spa Jan Pye, Mayor Pro Tem Rolf Hoehn, Vice Chairman Indian Wells Tennis Garden Robert Del Mas, Secretary Richard Balocco, Council Member X Empire Polo -

Interviews: It's 1970S Again with Walton Sisters, Pamela Sue Martin

Interviews: It’s 1970s Again With Walton Sisters, Pamela Sue Martin Published on HollywoodChicago.com (http://www.hollywoodchicago.com) Interviews: It’s 1970s Again With Walton Sisters, Pamela Sue Martin Submitted by PatrickMcD [1] on December 31, 2011 - 6:28pm 1970s [2] Hardy Boys [3] Hollywood Celebrities & Memorabilia Show [4] HollywoodChicago.com Content [5] Interview [6] Joe Arce [7] Judy Norton [8] Mary McDonough [9] Nancy Drew [10] Pamela Sue Martin [11] Patrick McDonald [12] The Waltons [13] CHICAGO – This year marked the 40th anniversary of the premiere of “The Waltons,” one of the most beloved TV series of the 1970s. Two actresses who portrayed Mary Ellen and Erin Walton, Mary McDonough and Judy Norton, appeared at the “Hollywood Celebrities & Memorabilia Show,” along with Pamela Sue Martin of TV’s “The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries’ (1977). HollywoodChicago.com was at the event to interview all three ‘70s icons, with photographer Joe Arce producing his usual stellar portraiture. Judy Norton, Mary Ellen Walton on “The Waltons” Judy Norton was memorable as Mary Ellen Walton, adding a little passion to the often saccharine image of the TV family. She also gained a bit of notoriety after the series ended by posing for Playboy in the mid-1980s. She is still working in the business, as an actress, singer, writer and director. She recently appeared on the “Today” show, reuniting with the cast of the Walton family on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of “The Homecoming,” the Christmas-themed pilot of the long-running series. Page 1 of 8 Interviews: It’s 1970s Again With Walton Sisters, Pamela Sue Martin Published on HollywoodChicago.com (http://www.hollywoodchicago.com) Judy Norton at the Hollywood Celebrities & Memorabilia Show, Chicago, March 26th, 2011 Photo credit: Joe Arce of Starstruck Foto for HollywoodChicago.com HollywoodChicago.com: Since you literally grew up on television during your teenage years, did you ever have any trouble distinguishing Judy Norton from Mary Ellen Walton? Judy Norton: No.