Interaction Between Comparative Psychology and Cognitive Development Beck, Sarah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Connecticut Department of Public Health

STATE OF CONNECTICUT DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH VERIFICATION OF DOCTORAL PROGRAM Applicant: Please complete the top portion of this form and forward it to the university where you received your doctoral degree. Name: _______________________________ Student identification number: __________________ University name and location: ________________________________________________________ TO BE COMPLETED BY EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION ONLY The University must complete the remainder of this form for the above referenced applicant and return the form directly to the address listed below. The applicant completed a doctoral program of study within the Department of __________________ Please specify type of psychology program: clinical psychology counseling psychology school psychology other: ___________________________________________________ Was the candidate's program of study APA accredited at the time of the applicant’s completion? YES NO Did this applicant complete a course of studies encompassing a minimum of three academic years of full- time graduate study, of which a minimum of one academic year of full-time academic graduate study in psychology in residence at the institution granting the doctoral degree? YES NO Did this applicant complete coursework in scientific methods as follows (Check all that apply and indicate number of credit hours): Coursework No. of Credit Hours Research design and methodology Statistics and psychometrics Biological bases of behavior, for example, physiological psychology, comparative psychology, neuro-psychology, -

International Journal of Comparative Psychology

eScholarship International Journal of Comparative Psychology Title The State of Comparative Psychology Today: An Introduction to the Special Issue Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0mn8n8bc Journal International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 31(0) ISSN 0889-3675 Authors Abramson, Charles I. Hill, Heather M. Publication Date 2018 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 2018, 31 Charles Abramson Special Issue Editor Peer-reviewed* The State of Comparative Psychology Today: An Introduction to the Special Issue Charles I. Abramson 1 and Heather M. Hill 2 1 Oklahoma State University, U.S.A. 2 St. Mary’s University, U.S.A. Comparative psychology has long held an illustrious position in the pantheon of psychology. Depending on who you speak with, comparative psychology is as strong as ever or in deep decline. To try and get a handle on this the International Journal of Comparative Psychology has commissioned a special issue on the State of Comparative Psychology Today. Many of the articles in this issue were contributed by emanate comparative psychologists. The topics are wide ranging and include the importance of incorporating comparative psychology into the classroom, advances in automating, comparative cognition, philosophical perspectives surrounding comparative psychology, and issues related to comparative methodology. Of special interest is that the issue contains a listing of comparative psychological laboratories and a list of comparative psychologists who are willing to serve as professional mentors to students interested in comparative psychology. We hope that this issue can serve as a teaching resource for anyone interested in comparative psychology whether as part of a formal course in comparative psychology or as independent readings. -

Journal of Comparative Psychology Inaccessibility of Reinforcement Increases Persistence and Signaling Behavior in the Fox Squirrel (Sciurus Niger) Mikel M

Journal of Comparative Psychology Inaccessibility of Reinforcement Increases Persistence and Signaling Behavior in the Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger) Mikel M. Delgado and Lucia F. Jacobs Online First Publication, April 14, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/com0000021 CITATION Delgado, M. M., & Jacobs, L. F. (2016, April 14). Inaccessibility of Reinforcement Increases Persistence and Signaling Behavior in the Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger). Journal of Comparative Psychology. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/com0000021 Journal of Comparative Psychology © 2016 American Psychological Association 2016, Vol. 130, No. 3, 000 0735-7036/16/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/com0000021 Inaccessibility of Reinforcement Increases Persistence and Signaling Behavior in the Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger) Mikel M. Delgado and Lucia F. Jacobs University of California, Berkeley Under natural conditions, wild animals encounter situations where previously rewarded actions do not lead to reinforcement. In the laboratory, a surprising omission of reinforcement induces behavioral and emotional responses described as frustration. Frustration can lead to aggressive behaviors and to the persistence of noneffective responses, but it may also lead to new behavioral responses to a problem, a potential adaptation. We assessed the responses to inaccessible reinforcement in free-ranging fox squirrels (Sciurus niger). We trained squirrels to open a box to obtain food reinforcement, a piece of walnut. After 9 training trials, squirrels were tested in 1 of 4 conditions: a control condition with the expected reward, an alternative reinforcement (a piece of dried corn), an empty box, or a locked box. We measured the presence of signals suggesting arousal (e.g., tail flags and tail twitches) and found that squirrels performed fewer of these behaviors in the control condition and increased certain behaviors (tail flags, biting box) in the locked box condition, compared to other experimental conditions. -

The Behavioral Neuroscientist and Comparative Psychologist

BUSINESS NAME The Behavioral Neuroscientist and Comparative Psychologist Division 6, American Volume 25, Issue 2 Fall/Winter, 2010 Psychological Association Editor A Message From Division 6 President Gordon Burghardt David J. Bucci, PhD Dartmouth College As incoming president of Division 6 I was not totally aware of what would be entailed. Now that I am in the thick of helping plan the APA convention program, facilitating the operation of our various Division President committees such as Membership, Fellows, Awards, Gordon Burghhardt, PhD Students, and others, I see that I, along with many other Div. 6 members, take for granted the ‗gift‘ we have as one of the oldest APA divisions and the sup- port and resources available to us from APA. None- theless, there are problems that we need to discuss both within and across the many APA Divisions. In Inside this issue: this and future newsletter essays I want to raise is- sues, present proposals, and try to elicit some feed- back and dialogue that can be discussed within our Message from 1, 4- division listserv [email protected] or through President 5 personal exchanges at [email protected]. In any event, vigorous conversations seem to be needed. Membership Crisis & the Scientific Imperative APA council, but only one seat due to our small Division 6 2-3 The Division Services office of APA is concerned membership. Still, our impact on the field, as Officers about the health of all divisions, as many APA mem- shown by articles and research blurbs in the APA bers are not affiliating with any division and those Monitor and the flagship American Psychologist, belie remaining in divisions are rapidly aging and member- our small numbers. -

Regulations of Connecticut State Agencies Psychologist Educational and Work Experience Requirements

Regulations of Connecticut State Agencies Psychologist Educational and Work Experience Requirements Sec. 20-188-1. Definitions (a) "Accreditation by the American Psychological Association" shall mean that: (1) the program held provisional accreditation status or full accreditation status throughout the period of the applicant's enrollment, provided said provisional status subsequently progressed without interruption to full accreditation; or (2) the program held probationary accreditation status during the applicant's enrollment and, upon termination of said probationary status, subsequently achieved full accreditation. (b) "Recognized regional accrediting body" shall mean one of the following accrediting bodies: New England Association of Schools and Colleges; Middle States Commission on Higher Education; North Central Association of Colleges and Schools; Northwest Association of Colleges and Universities; Southern Association of Colleges and Schools; and Western Association of Schools and Colleges. (c) "Accreditation by a recognized regional accrediting body" shall mean that: (1) the institution held accreditation status or candidacy for accreditation throughout the period of the applicant's enrollment, provided said candidacy status subsequently progressed without interruption to full accreditation; or (2) the institution held accreditation status under probation or show-cause order during the applicant's enrollment and, upon termination of said probation or show-cause order, accreditation status was maintained without interruption. -

Thinking Pigs: Cognition, Emotion, and Personality

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 2016 Thinking Pigs: Cognition, Emotion, and Personality Lori Marino The Kimmela Center for Animal Advocacy Christina M. Colvin Emory University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/mammal Part of the Animals Commons, Animal Studies Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Marino, Lori and Colvin, Christina M., "Thinking Pigs: Cognition, Emotion, and Personality" (2016). Mammalogy Collection. 1. https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/mammal/1 This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THINKING PIGS: Cognition, Emotion, and Personality © Farm Sanctuary AN EXPLORATION OF THE COGNITIVE COMPLEXITY OF SUS DOMESTICUS, THE DOMESTIC PIG By Lori Marino and Christina M. Colvin Based on: Marino L & Colvin CM (2015). Thinking pigs: A comparative review of cognition, emotion and personality in Sus domes- ticus. International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 28: uclapsych_ijcp_23859. Retrieved from: https://escholarship.org/uc/ item/8sx4s79c © Kimmela Center for Animal Advocacy Thinking Pigs: Cognition, Emotion, and Personality AN EXPLORATION OF THE COGNITIVE COMPLEXITY OF SUS DOMESTICUS, THE DOMESTIC PIG he pig of our imagination is the Tom Sawyer, the Scarlett O’Hara, the TABLE OF CONTENTS TFalstaff of the farm animal world: clever, charismatic, mischievous, and gluttonous. References to road hogs, going whole hog or hog wild, 3 A Pig’s World pigging out, and casting pearls before swine pepper our everyday language. In the Chinese zodiac and literature, the pig characterizes strong 4 Object Discrimination emotions, lack of restraint, and virility. -

Psychology (PSY) 1

Psychology (PSY) 1 Psychology (PSY) Courses PSY 0815. Language in Society. 3 Credit Hours. How did language come about? How many languages are there in the world? How do people co-exist in countries where there are two or more languages? How do babies develop language? Should all immigrants take a language test when applying for citizenship? Should English become an official language of the United States? In this course we will address these and many other questions, taking linguistic facts as a point of departure and considering their implications for our society. Through discussions and hands-on projects, students will learn how to collect, analyze, and interpret language data and how to make informed decisions about language and education policies as voters and community members. NOTE: This course fulfills the Human Behavior (GB) requirement for students under GenEd and Individual & Society (IN) for students under Core. Students cannot receive credit for this course if they have successfully completed any of the following: ANTH 0815/0915, Asian Studies 0815, Chinese 0815, CSCD 0815, EDUC 0815/0915, English 0815, Italian 0815, Russian 0815, or Spanish 0815. Course Attributes: GB Repeatability: This course may not be repeated for additional credits. PSY 0816. Workings of the Mind. 3 Credit Hours. In this course we will discuss conscious and unconscious mental processes. We will start by considering the nature of the unconscious mind and will examine evidence for the existence of unconscious processes in memory, problem solving, behavior in social settings, and our attitudes, beliefs, and opinions. We will then study the nature of consciousness from psychological and philosophical perspectives, with a focus on trying to answer the questions of: what is consciousness, what does consciousness do, and why does consciousness exist. -

Has Scala Naturae Thinking Come Between Neuropsychology and Comparative Neuroscience?

eScholarship International Journal of Comparative Psychology Title Has Scala Naturae Thinking Come Between Neuropsychology and Comparative Neuroscience? Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4cj5m8d9 Journal International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 16(1) ISSN 0889-3675 Author Marino, Lori Publication Date 2003-12-31 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 2003, 16, 28-32. Copyright 2003 by the International Society for Comparative Psychology Has Scala Naturae Thinking Come Between Neuropsychology and Comparative Neuroscience? Lori Marino Emory University, U.S.A. Within the broad domain of neuroscience there is a divergence between those journals that focus on human clinical topics and those that take a decidedly comparative evolutionary and nonhuman approach. This distinction reflects a deeper separation between two branches of neuroscience: the human neuropsychological and the comparative neuroscience fields. I argue that this divergence is a reflection of scala naturae thinking and that greater strides in scientific thinking can be gained by overcoming this bias in favor of deep continuity across the human and nonhuman subdomains of neuroscience. Two Separate Disciplines If one takes even a superficial glance at the distribution of scientific journals in the broad domain of neuroscience it would be difficult to ignore a particularly obvious divergence between those journals that focus on human clinical issues and those categorized by a comparative evolutionary approach. As just one example, The American Psychological Association’s description of its prominent journal Neuropsychology reads as follows: Sought are submissions of human experimental, cognitive, and behavioral research with implications for neuropsychological theory and practice. -

PS3036 Evolution and Comparative Psychology

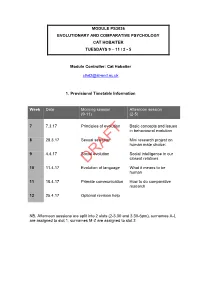

MODULE PS3036 EVOLUTIONARY AND COMPARATIVE PSYCHOLOGY CAT HOBAITER TUESDAYS 9 – 11 / 2 - 5 Module Controller: Cat Hobaiter [email protected] 1. Provisional Timetable Information Week Date Morning session Afternoon session (9-11) (2-5) 7 7.3.17 Principles of evolution Basic concepts and issues in behavioural evolution 8 28.3.17 Sexual selection Mini research project on human mate choice: 9 4.4.17 Social evolution Social intelligence in our closest relatives DRAFT 10 11.4.17 Evolution of language What it means to be human 11 18.4.17 Primate communication How to do comparative research 12 25.4.17 Optional revision help NB. Afternoon sessions are split into 2 slots (2-3.30 and 3.30-5pm), surnames A-L are assigned to slot 1, surnames M-Z are assigned to slot 2. 2 2. Aim of the Module The aim of this module is to gain a deep understanding of the principles of natural and sexual selection and how these processes have shaped the mind and behaviour of humans and other animals. This requires integration of a variety of methods, ranging from archaeology to anthropology, but the principal methodological tool is the comparative approach. We will compare the behaviour and cognitive capacities of primates and other species to draw conclusions about the evolution of our own mind, brain and behaviour. This module will take into account that students have a non-standard background in Psychology. Morning lectures will cover theoretical material, afternoon workshops will focus on the practical application of these ideas in research: both aspects will be assessed at the end of the module in a take-home format exam. -

What Should Comparative Psychology Compare?

eScholarship International Journal of Comparative Psychology Title What Should Comparative Psychology Compare? Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6s93w004 Journal International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 2(3) ISSN 0889-3675 Authors Innis, N. K. Staddon, J. E. R. Publication Date 1989 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The International Journal of Comparative Psychology, Vol. 2, No. 3, Spring 1989 WHAT SHOULD COMPARATIVE PSYCHOLOGY COMPARE? N. K. Innis J. E. R. Staddon University of Western Ontario and Duke University ABSTRACT: Scientific psychology is a search for the mechanisms that underlie behavior. Following a brief history of the comparative psychology of learning, we suggest that comparative psychologists should focus on mechanisms rather than performances, and provide an example of a simple, formal mechanism to illustrate this point. The modern history of comparative psychology begins with Charles Darwin (1809-1882). Darwin's theoryofevolution through variation and natural selection has provided a conceptual framework for psychology as well as for biology. As Tooby and Cosmides (p. 175) point out, the two parts to Darwinian evolution have led to two kinds of approach to the study of animal behavior: an emphasis on variation underlies the phylo- genetic approach; an emphasis on natural selection underlies the study of adaptation. In this introductory paper we consider the comparative psychology of learning, perhaps the most complex behavioral adapta- tion and the topic most popular with psychologists. After a brief over- view of some historical highlights, we focus on the issue of comparison. -

Comparative Developmental Psychology: How Is Human Cognitive Development Unique?

Evolutionary Psychology www.epjournal.net – 2014. 12(2): 448-473 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ Original Article Comparative Developmental Psychology: How is Human Cognitive Development Unique? Alexandra G. Rosati, Department of Psychology, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. Email: [email protected] (Corresponding author). Victoria Wobber, Department of Psychology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. Kelly Hughes, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA. Laurie R. Santos, Department of Psychology, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. Abstract: The fields of developmental and comparative psychology both seek to illuminate the roots of adult cognitive systems. Developmental studies target the emergence of adult cognitive systems over ontogenetic time, whereas comparative studies investigate the origins of human cognition in our evolutionary history. Despite the long tradition of research in both of these areas, little work has examined the intersection of the two: the study of cognitive development in a comparative perspective. In the current article, we review recent work using this comparative developmental approach to study non-human primate cognition. We argue that comparative data on the pace and pattern of cognitive development across species can address major theoretical questions in both psychology and biology. In particular, such integrative research will allow stronger biological inferences about the function of developmental change, and will be critical in addressing how humans come to acquire species-unique cognitive abilities. Keywords: comparative development, primate cognition, heterochrony, human adaptation ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ Introduction Human behavior is strikingly different from that of other animals. We speak language, routinely cooperate with others to reach complex shared goals, engage in abstract reasoning and scientific inquiry, and learn a rich set of sophisticated cultural behaviors from others. -

The Evolution of Comparative Psychology

eScholarship International Journal of Comparative Psychology Title Introduction: The Evolution of Comparative Psychology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nm888vh Journal International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 2(3) ISSN 0889-3675 Author Innis, Nancy K. Publication Date 1989 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The International Journal of Comparative Psychology, Vol. 2, No. 3, Spring 1989 INTRODUCTION: THE EVOLUTION OF COMPARATIVE PSYCHOLOGY Nancy K. Innis University of Western Ontario Why do psychologists study the behavior of animals? The usual response to this question, even from many comparative psychologists, is that explaining animal behavior will help us understand human behav- ior, and understanding human behavior is the ultimate goal of psychol- ogy. Has this, in fact, been the aim of animal psychology, and if so, has it succeeded? As scientific disciplines go, comparative psychology is relatively recent. Following the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species and his subsequent discourse on the evolution of intelligence (Darwin, 1859; 1871; 1872), psychologists became interested in studying animals and their relationship to humans. Early on, a fairly wide range of topics was explored and a large number of animal species studied. However, this was soon to change. The reader is referred to two excellent recent publications — Boakes' (1984) From Darwin to Behaviourism and Richards' (1987) Darwin and the Emergence of Theories of Mind and Behavior—which examine this early period. The focus of inquiry narrowed, particularly in North America, when Behaviorism, in all its various forms, began to dominate psychology early in the twentieth century.