Seher: a New Dawn Breaks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compounding Injustice: India

INDIA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) – July 2003 Afsara, a Muslim woman in her forties, clutches a photo of family members killed in the February-March 2002 communal violence in Gujarat. Five of her close family members were murdered, including her daughter. Afsara’s two remaining children survived but suffered serious burn injuries. Afsara filed a complaint with the police but believes that the police released those that she identified, along with many others. Like thousands of others in Gujarat she has little faith in getting justice and has few resources with which to rebuild her life. ©2003 Smita Narula/Human Rights Watch COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: THE GOVERNMENT’S FAILURE TO REDRESS MASSACRES IN GUJARAT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] July 2003 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: The Government's Failure to Redress Massacres in Gujarat Table of Contents I. Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Impunity for Attacks Against Muslims............................................................................................................... -

Narendra Modi: Architect of Gujarat Genocide 2002

Modi: Architect of Gujarat Genocide. Targetting of Women May 01, 2002. The Milli Gazette. Syed Ubaidur Rahman. Were sexual crimes in Gujarat planned? Ahmedabad: Women have been the main target of the rioters in Gujarat. After visiting the state for more than a week and meeting hundreds of people in different camps spread over the four most affected districts of the state including Panchmahal, (under which Godhra comes) Baroda, Anand and Ahmadabad, I have reached the conclusion that women were consciously and specially targeted by the rioters who were being controlled by the VHP and Bajrang Dal criminals besides the members of the RSS and the BJP. The way the Hindu mobs acted while brutally dishonouring Muslim women will put the Serbs in Bosnia and Kosovo to shame. Wherever there were killings, there were large scale rapes of Muslim women irrespective of age differences. There are incidents when all this was done while their fathers, brothers and husbands were made to witness this brutality after being made captives. And at times all this was done inside the village mosques. Fatima Bibi Md Yaqub Sheikh whose family lost 19 members including her sisters and brothers says that whatever they did could have been justified, except the way they raped women. She says that when her family tried to flee Naroda Patia, the area where 90 people were burnt alive they all requested the police to save them, but police instead of doing anything for their safety asked them to surrender themselves to the mob. She says that her sister and her niece both were repeatedly raped by the mob. -

Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There Were Few Women Painters in Colonial India

I. (A) Personal Details Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar Paper Coordinator Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Author Dr. Archana Verma Independent Scholar Content Reviewer (CR) Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Language Editor (LE) Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar (B) Description of Module Items Description of Module Subject Name Women’s Studies Paper Name Women and History Module Name/ Title, Women performers in colonial India description Module ID Paper- 3, Module-30 Pre-requisites None Objectives To explore the achievements of women performers in colonial period Keywords Indian art, women in performance, cinema and women, India cinema, Hindi cinema Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There were few women painters in Colonial India. But in the performing arts, especially acting, women artists were found in large numbers in this period. At first they acted on the stage in theatre groups. Later, with the coming of cinema, they began to act for the screen. Cinema gave them a channel for expressing their acting talent as no other medium had before. Apart from acting, some of them even began to direct films at this early stage in the history of Indian cinema. Thus, acting and film direction was not an exclusive arena of men where women were mostly subjects. It was an arena where women became the creators of this art form and they commanded a lot of fame, glory and money in this field. In this module, we will study about some of these women. Nati Binodini (1862-1941) Fig. 1 – Nati Binodini (get copyright for use – (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Binodini_dasi.jpg) Nati Binodini was a Calcutta based renowned actress, who began to act at the age of 12. -

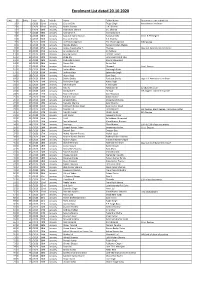

Enrolment List Dated 20.10.2020

Enrolment List dated 20.10.2020 S.No. D/ EnNo Year Date Month Name Father Name Documents to be submitted 1 D/ 1 /2020 02nd January, Gaurav Dixit Tejpal Singh Attendance Certificate 2 D/ 2 /2020 02nd January, Mohit Sharma U.K. Sharma 3 D/ 3 /2020 06th January, Shailendra Sharma S.C. Sharma 4 D/ 4 /2020 06th January, Kasiraman K. Kannuchamy K. 5 D/ 5 /2020 06th January, Saurabh Kumar Suman Ramakant Jha Grad. & PG Degree 6 D/ 6 /2020 06th January, Gaurav Sharma K.K. Sharma 7 D/ 7 /2020 06th January, Jai Prakash Agrawal Tek Chand Agrawal FIR Pending 8 D/ 8 /2020 07th January, Renuka Madan Balram Krishan Madan 9 D/ 9 /2020 07th January, Arokia Arputha Raj T. Thomas Org. LLB. Attendance Certificate 10 D/ 10 /2020 07th January, Anandakumar P. O. Paldurai 11 D/ 11 /2020 08th January, Anurag Kumar Late B.L. Grover 12 D/ 12 /2020 08th January, Atika Alvi Late Umar Mohd. Alvi 13 D/ 13 /2020 08th January, Shahrukh Kirmani Shariq Mahmood 14 D/ 14 /2020 08th January, Shreya Bali Sanjay Bali 15 D/ 15 /2020 09th January, Ashok Kumar Dhanpal Grad. Degree 16 D/ 16 /2020 09th January, Sachin Bhati Mansingh Bhati 17 D/ 17 /2020 09th January, Jaskiran Kaur Satwinder Singh 18 D/ 18 /2020 09th January, Hitain Bajaj Sunil Bajaj 19 D/ 19 /2020 09th January, Shikha Shukla Ravitosh Shukla Org. LLB. Attendace Certificate 20 D/ 20 /2020 10th Janaury, Paramjeet Singh Avtar Singh 21 D/ 21 /2020 10th Janaury, Kalimuthu M. K. Murugan 22 D/ 22 /2020 13th January, Raju N. -

Nautch’ to the Star-Status of Muslim Women of Hindustani Cinema

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-2, Issue-7, 2016 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in A Journey from the Colonial Stigma of ‘Nautch’ To the Star-Status of Muslim Women of Hindustani Cinema Ayesha Arfeen Research Scholar, CSSS/SSS, J.N.U, New Delhi Abstract : This paper tries to explore and indulge Pran Nevile maintains that while the Mughal India into the debate of how the yesteryears tawaifs were saw the advent of the nautch girl on the cultural reduced to mere prostitutes and hence the stigma landscape of the country and her rise to the pinnacle of glory, the annexation by the British of attached to them in the colonial period and how Awadh (1856) in the north and Tanjore (1855) in with the post-colonial period, the stigma is erased the south - the two dominant centres of Indian art by the rising to fame of Muslim actresses of and culture - foreshadowed her decline and fall. Hindustani film industry. This paper turns out to be Pran Nevile, who himself hails from India (British a comparative study of the ‘nautch’ girls as India) surprises me when he uses the term ‘nautch’ portrayed by the British and their downfall on one in the above statement, for the larger than life hand; and the Muslim doyens of Hindustani cinema ‘tawaifs’ of North India. as stars on the other. The tawaifs were professional women performing artists who functioned between the nineteenth and Keywords: Muslim Women, Star Status, Muslim early twentieth century in north India. The word Actresses, Stardom, Hindustani Cinema, Film ‘tawaif’ is believed to have come from the Persian Stars, Nautch, Tawaif tawaif of circumambulation of the kaaba and refers to her movement around the mehfil space, the circle INTRODUCTION. -

Westminsterresearch Bombay Before Bollywood

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Bombay before Bollywood: the history and significance of fantasy and stunt film genres in Bombay cinema of the pre- Bollywood era Thomas, K. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Prof Katharine Thomas, 2016. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] BOMBAY BEFORE BOLLYWOOD: THE HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE OF FANTASY AND STUNT FILM GENRES IN BOMBAY CINEMA OF THE PRE-BOLLYWOOD ERA KATHARINE ROSEMARY CLIFTON THOMAS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University Of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Published Work September 2016 Abstract This PhD by Published Work comprises nine essays and a 10,000-word commentary. Eight of these essays were published (or republished) as chapters within my monograph Bombay Before Bollywood: Film City Fantasies, which aimed to outline the contours of an alternative history of twentieth-century Bombay cinema. The ninth, which complements these, was published in an annual reader. This project eschews the conventional focus on India’s more respectable genres, the so-called ‘socials’ and ‘mythologicals’, and foregrounds instead the ‘magic and fighting films’ – the fantasy and stunt genres – of the B- and C-circuits in the decades before and immediately after India’s independence. -

![5482 @<¶D 4`Griz 4`Gzdyzv]U V^Vcxv Tj](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6914/5482-%C2%B6d-4-griz-4-gzdyzv-u-v-vcxv-tj-1986914.webp)

5482 @<¶D 4`Griz 4`Gzdyzv]U V^Vcxv Tj

1 3 12 3"+ "+ + SIDISrtVUU@IB!&!!"&#S@B9IV69P99I !%! %! ' %'()!%*+#,-. -4545+ 6'7 )-'(/ ! 7 ((#,&(:6 ;;%()(.(0(,&#.6 (.6#(*#(2 #%&-/0$ *%0(*%-*(#6$(. $&6%&62 6%02#(&*(0%&62( $#62*.0, .(%&.(&-. %(&'(.% #%.(- %8#.(*(9& (8$(( 4 !"#$ %%& 5 4( 6! # ( / ./010#2 3 #00 R #$#%& General VG Somani said the efficacy of the British-devel- & earing up to launch one of oped AstraZeneca/Oxford vac- Gthe world’s largest coron- cine is 70.42 per cent, though he avirus vaccination drive any- did not give out the efficacy per % $ time soon, India on Sunday cent of the jab developed by the gave final approval for the Hyderabad-based biotechnolo- emergency use of Hyderabad- gy firm, Bharat Biotech. #$#%& research experts were not con- based Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin Somani, however, vinced as they termed it ‘a and the Serum Institute of described the Indian-devel- mid concerns raised by dangerous step’ given that India’s Covishield. Both vac- oped Covaxin vaccine as “safe Avarious quarters regard- details of Stage 3 clinical trials #$#%& BJP” and said he would not cines are being produced in the which provides a robust ing the efficacy of the Covaxin were yet not available. take the shot. On Sunday, the country. immune response.” He said indigenously developed by They argued that the prob- he grant of approval to former Uttar Pradesh Chief India’s approval of the UK- the Indian vaccine was Bharat Biotech that is yet to lem is that the Government in TBharat Biotech’s Covid-19 Minister said the Covid-19 developed AstraZeneca/Oxford approved “in the public inter- complete phase 3 trial, the its eagerness to promote ‘vocal vaccine for “emergency use” vaccination programme is a University jab follows Britain’s est as an abundant precaution, DCGI said it will be used in for local’ notion has bypassed has kicked a major controversy “sensitive process”, and the recent approval of the vaccine. -

Goa Upgs 2018

State People Group Name Language Religion Pop. Total % Christian Goa Adi Dravida Tamil Hinduism 80 0 Goa Adi Karnataka Kannada Hinduism 80 0 Goa Agamudaiyan Tamil Hinduism 20 0 Goa Agamudaiyan Nattaman Tamil Hinduism 20 0 Goa Ager (Hindu traditions) Kannada Hinduism 1310 0 Goa Agri Marathi Hinduism 5750 0 Goa Ajila Malayalam Hinduism 500 0 Goa Andh Marathi Hinduism 20 0 Goa Ansari Urdu Islam 560 0 Goa Aray Mala Telugu Hinduism 10 0 Goa Arayan Malayalam Hinduism 30 0 Goa Arora (Sikh traditions) Punjabi, Eastern Other 90 0 Goa Arunthathiyar Telugu Hinduism 20 0 Goa Arwa Mala Tamil Hinduism 10 0 Goa Badhai (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 15780 0 Goa Bagdi Hindi Hinduism 30 0 Goa Bagdi (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism 50 0 Goa Bahrupi Marathi Hinduism 90 0 Goa Baira Kannada Hinduism 50 0 Goa Bairagi (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 1480 0 Goa Bakad Kannada Hinduism 550 0 Goa Bakuda Tulu Hinduism 20 0 Goa Balagai Kannada Hinduism 30 0 Goa Balai (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 20 0 Goa Balija (Hindu traditions) Kannada Hinduism 280 0 Goa Bandi (Hindu traditions) Kannada Hinduism 810 0 Goa Bania Agarwal Hindi Hinduism 2530 0 Goa Bania Chaturth Marathi Other 130 0 Goa Bania Chetti Tamil Hinduism 5090 0 Goa Bania Gujar Gujarati Hinduism 1860 0 Goa Bania Kasar Hindi Hinduism 1110 0 Goa Bania Khedayata Gujarati Hinduism 50 0 Goa Bania Komti Telugu Hinduism 2360 0 Goa Bania Mahur Hindi Hinduism 2280 0 Goa Bania unspecified Hindi Hinduism 50400 0 Goa Banijiga Kannada Hinduism 1380 0 Goa Banjara (Hindu traditions) Lambadi Hinduism 2050 0 Goa -

Maharashtra Upgs 2018

State People Group Language Religion Population % Christian Maharashtra Adi Adi Unknown 40 0 Maharashtra Adi Andhra Telugu Hinduism 2500 3.2 Maharashtra Adi Dravida Tamil Hinduism 39610 3.534461 Maharashtra Adi Karnataka Kannada Hinduism 7260 0.4132231 Maharashtra Agamudaiyan Tamil Hinduism 4290 0 Maharashtra Agamudaiyan Mukkulattar Tamil Hinduism 670 0 Maharashtra Agamudaiyan Nattaman Tamil Hinduism 2280 0 Maharashtra Agaria (Hindu traditions) Agariya Hinduism 110 0 Maharashtra Ager (Hindu traditions) Kannada Hinduism 7710 0 Maharashtra Aghori Hindi Hinduism 90 0 Maharashtra Agri Marathi Hinduism 336690 0 Maharashtra Aguri Bengali Hinduism 1300 0 Maharashtra Ahmadi Urdu Islam 1870 0 Maharashtra Ahom Assamese Hinduism 30 0 Maharashtra Alitkar Salankar Marathi Hinduism 750 0 Maharashtra Alkari Marathi Hinduism 500 0 Maharashtra Alwar Marwari Hinduism 160 0 Maharashtra Ambalavasi Malayalam Hinduism 30 0 Maharashtra Anamuk Telugu Hinduism 2010 0 Maharashtra Andh Marathi Hinduism 470180 0.0148879 Maharashtra Ansari Urdu Islam 687760 0 Maharashtra Arab Arabic, Mesopotamian Spoken Islam 750 0 Maharashtra Arain (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam 200 0 Maharashtra Arakh Hindi Hinduism 1600 0 Maharashtra Aray Mala Telugu Hinduism 1670 0 Maharashtra Arayan Malayalam Hinduism 80 0 Maharashtra Arora (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 1630 0 Maharashtra Arora (Sikh traditions) Punjabi, Eastern Other / Small 5610 0 Maharashtra Arwa Mala Tamil Hinduism 1590 0 Maharashtra Assamese (Muslim traditions) Assamese Islam 250 0 Maharashtra Atari Urdu Islam 1860 0 -

Bikaner State

CENSOS OF INDIA, 1 93 1 . VOLUME I. BIKANER STATE. Part II TABLES CENSOS OF INDIA, 1931. VOLUME I BIKANER ST ATE. Part II TABLES COMPILED BY Ral Babadup D. M. Nanavati, B .. A., LL.B., Superintendent, Census Operations, B"kaner State. PRINTED BY K. D. SETH AT THE NEWUL KISHOHE PRESS, LUCKNOW. 1932. TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAaE. INTRODUCTORY NOTE. 1 Statelftent 0" Co.... e.ponding Table. i.. 't 951 't and ... 98 ... 3 IMPERIAL TABLES. 1i--8O Table I.-Area. HOUBe8 and POpulabOD 1i-6 'rable 1:1:.-Variation in Popula.b.on &inco 1881 '1--9 orable X:lJ:.-ToWllB and VIllages cla.asi:b.ed by Populat1.oD 11-1. Table IV.-ToWDll classIfied by Populatl.on WIth VanatJ.On since 1881 18-14- 'rable V. -Towns arranged by Distncts with Population by Religion lli-16 Table VJ:.-Birth-pla.ce 1'1-18 ~ble Vl::I. -Ago. Sex and Civil Condition l.9-", Table VIII.-CivU Condition by Age for Selected Canes iI&-_ Table IX.-Inftnnitios 81-U Table X.-Occu.pation or Means of Livelihood 33-440 Table XX.-Occu.patloDS by Selocted. Caste. Tribe 01' Raoo 406-4-" Table XIZZ.-BducatioD by ReligioD and Age In the State 4.9-6. "rable XIV.-Educatl.on by Seleoted Castes. Tribe. 01' Races .58-&8 Table XV.--La.ugua.ge 1i'1-09 Table XVX.-RebgJ.OD 61-64- Table XVII.-B.a.co. Tnbe or Caste 6Ji-'18 Table XV1:II.-Variatlon of Population of Selected Tnbes 77-'18 Table XIX -Europeans aDd Allied a.ces and Anglo-IncUau8 By Raco '19-80 PROVINCIAL TABLES. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & LR-Unreached People Groups = LR-Upgs

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs - of INDIA Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net Western edition To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of India INDIA SUMMARY: 2,717 total People Groups; 2,445 LR-UPG India has 1/3 of all UPGs in the world; the most of any country LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 * * * "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" * * * India ISO codes are used for some Indian states as follows: AN = Andeman & Nicobar. JH = Jharkhand OD = Odisha AP = Andhra Pradesh+Telangana JK = Jammu & Kashmir PB = Punjab AR = Arunachal Pradesh KA = Karnataka RJ = Rajasthan AS = Assam KL = Kerala SK = Sikkim BR = Bihar ML = Meghalaya TN = Tamil Nadu CT = Chhattisgarh MH = Maharashtra TR = Tripura DL = Delhi MN = Manipur UT = Uttarakhand GJ = Gujarat MP = Madhya Pradesh UP = Uttar Pradesh HP = Himachal Pradesh MZ = Mizoram WB = West Bengal HR = Haryana NL = Nagaland Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Full Name Dr. Neeraj Silawat Date of Birth 01/12/1975 Address Residential Mahadev Desai Sharirik Shikshan Mahavidyalaya, Sevak Niwas, Sadra, Ta. Dist. Gandhinagar. Current Position Assistant Professor, Mahadev Desai Sharirik Shiskshan Mahavidyalaya, Gujarat Vidyapith, Sadra, Ta. Dist. Gandhinagar. E-mail [email protected] Academic Qualifications Exam Board/University Subjects Year Division/ passed Grade/ Merit. M.Sc. Jain Vishva Bharati Institute, Yoga Education 2013 First in Yoga Ladnu, Rajasthan Division Ph.D. Gujarat Vidyapith, Ahmedabad Physical 2012 Awarded Education M.Phil. Vinayaka Missions University, Physical 2008 First Salem Education Division M.P.Ed. D.A.V.V. Indore Physical 1998 First Education Division Gold Medalist B.P.E. D.A.V.V. Indore Physical 1996 First Education Division Gold Medalist 1 Contribution to Teaching Subject Taught Course Name of University / Duration (Theory) Name College Institution History and Modern B.P.E. M.D.S.S. Mahavidyalaya Since 2001 Trends in Physical Sadra Education Exercise Physiology B.P.E. M.D.S.S. Mahavidyalaya Since 2009 Sadra Sports Injuries and B.P.Ed. M.D.S.S. Mahavidyalaya Since 2009 their Management Sadra Sports Medicine B.P.Ed. M.D.S.S. Mahavidyalaya Since 2015 Sadra Sports Science B.P.Ed. M.D.S.S. Mahavidyalaya From 2001 to Sadra 2014 Exercise Physiology M.P.Ed. M.D.S.S. Mahavidyalaya Since 2009 Sadra Subject Course Name of University / Duration Taught Name College (Practical) Institution Basketball B.P.E. M.D.S.S. Mahavidyalaya Since 2001 Sadra Badminton B.P.Ed. M.D.S.S. Mahavidyalaya Since 2001 Sadra Netball M.P.Ed.