Melochia (Malvaceae) En Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supporting Information Files

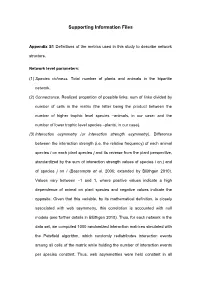

Supporting Information Files Appendix S1 Definitions of the metrics used in this study to describe network structure. Network level parameters: (1) Species richness. Total number of plants and animals in the bipartite network. (2) Connectance. Realized proportion of possible links: sum of links divided by number of cells in the matrix (the latter being the product between the number of higher trophic level species –animals, in our case- and the number of lower trophic level species –plants, in our case). (3) Interaction asymmetry (or interaction strength asymmetry). Difference between the interaction strength (i.e. the relative frequency) of each animal species i on each plant species j and its reverse from the plant perspective, standardized by the sum of interaction strength values of species i on j and of species j on i (Bascompte et al. 2006; extended by Blüthgen 2010). Values vary between −1 and 1, where positive values indicate a high dependence of animal on plant species and negative values indicate the opposite. Given that this variable, by its mathematical definition, is closely associated with web asymmetry, this correlation is accounted with null models (see further details in Blüthgen 2010). Thus, for each network in the data set, we computed 1000 randomized interaction matrices simulated with the Patefield algorithm, which randomly redistributes interaction events among all cells of the matrix while holding the number of interaction events per species constant. Thus, web asymmetries were held constant in all simulated networks, while interactions were reallocated between pairs of species according to species interaction frequencies. The difference between observed asymmetries of interaction strength and the mean asymmetry of interaction strength across the 1000 simulations gives the null- model-corrected asymmetry of interaction strength. -

Pine Island Ridge Management Plan

Pine Island Ridge Conservation Management Plan Broward County Parks and Recreation May 2020 Update of 1999 Management Plan Table of Contents A. General Information ..............................................................................................................3 B. Natural and Cultural Resources ...........................................................................................8 C. Use of the Property ..............................................................................................................13 D. Management Activities ........................................................................................................18 E. Works Cited ..........................................................................................................................29 List of Tables Table 1. Management Goals…………………………………………………………………21 Table 2. Estimated Costs……………………………………………………………….........27 List of Attachments Appendix A. Pine Island Ridge Lease 4005……………………………………………... A-1 Appendix B. Property Deeds………….............................................................................. B-1 Appendix C. Pine Island Ridge Improvements………………………………………….. C-1 Appendix D. Conservation Lands within 10 miles of Pine Island Ridge Park………….. D-1 Appendix E. 1948 Aerial Photograph……………………………………………………. E-1 Appendix F. Development Agreement………………………………………………….. F-1 Appendix G. Plant Species Observed at Pine Island Ridge……………………………… G-1 Appendix H. Wildlife Species Observed at Pine Island Ridge ……... …………………. H-1 Appendix -

TAXON:Melochia Umbellata

TAXON: Melochia umbellata SCORE: 9.0 RATING: High Risk (Houtt.) Stapf Taxon: Melochia umbellata (Houtt.) Stapf Family: Malvaceae Common Name(s): hierba del soldado Synonym(s): Melochia indica Kurz melochia Visenia indica C. C. Gmelin tangkal bintenoo Visenia umbellata Houtt. Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 23 Oct 2019 WRA Score: 9.0 Designation: H(Hawai'i) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Tropical Tree, Pioneer, Naturalized, Thicket-Forming, Wind-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 n outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed 304 Environmental weed 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, -

Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) in a Coastal Plain Area in the State of Paraná, Brazil

62 TROP. LEPID. RES., 26(2): 62-67, 2016 LEVISKI ET AL.: Butterflies in Paraná Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) in a coastal plain area in the state of Paraná, Brazil Gabriela Lourenço Leviski¹*, Luziany Queiroz-Santos¹, Ricardo Russo Siewert¹, Lucy Mila Garcia Salik¹, Mirna Martins Casagrande¹ and Olaf Hermann Hendrik Mielke¹ ¹ Laboratório de Estudos de Lepidoptera Neotropical, Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Caixa Postal 19.020, 81.531-980, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]٭ Abstract: The coastal plain environments of southern Brazil are neglected and poorly represented in Conservation Units. In view of the importance of sampling these areas, the present study conducted the first butterfly inventory of a coastal area in the state of Paraná. Samples were taken in the Floresta Estadual do Palmito, from February 2014 through January 2015, using insect nets and traps for fruit-feeding butterfly species. A total of 200 species were recorded, in the families Hesperiidae (77), Nymphalidae (73), Riodinidae (20), Lycaenidae (19), Pieridae (7) and Papilionidae (4). Particularly notable records included the rare and vulnerable Pseudotinea hemis (Schaus, 1927), representing the lowest elevation record for this species, and Temenis huebneri korallion Fruhstorfer, 1912, a new record for Paraná. These results reinforce the need to direct sampling efforts to poorly inventoried areas, to increase knowledge of the distribution and occurrence patterns of butterflies in Brazil. Key words: Atlantic Forest, Biodiversity, conservation, inventory, species richness. INTRODUCTION the importance of inventories to knowledge of the fauna and its conservation, the present study inventoried the species of Faunal inventories are important for providing knowledge butterflies of the Floresta Estadual do Palmito. -

Germination, Growth, Photosynthesis, and Osmotic Adjustment of Tossa Jute (Corchorus Olitrius L.) Seeds Under Saline Irrigation

Pol. J. Environ. Stud. Vol. 28, No. 2 (2019), 935-942 DOI: 10.15244/pjoes/85265 ONLINE PUBLICATION DATE: 2018-09-14 Original Research Germination, Growth, Photosynthesis, and Osmotic Adjustment of Tossa Jute (Corchorus olitrius L.) Seeds under Saline Irrigation Amira Racha Ben yakoub1, 2*, Samir Tlahig1, Ali Ferchichi3 1Arid and Oases Cropping Laboratory, Institute of Arid Lands (IRA), Médenine, Tunisia 2Faculty of Sciences of Tunis, University Campus, El Manar, Tunisia 3National Institute of Agronomy, Mahrajène City, Tunis, Tunisia Received: 15 January 2018 Accepted: 12 February 2018 Abstract A field experiment focusing on the response of Tossa jute Corchorus( olitorius L.) to salt stress at germination and vegetative growth stages was held in the Institute of Arid Lands of Medenine, Tunisia. Results showed that germinating rate after 24 hrs exceeded 50% under salt levels between 0 and 5 g.l-1. Indeed, salt stress levels delayed the initiation process and decreased significantly kinetics and rate of germination, which were severely limited at 9 and 10 g.l-1 NaCl. After one month of growth, Tossa jute seedlings were subjected to salt treatments of 2, 4, 6, and 8 g.l-1 NaCl. After four weeks of stress in pots, morphological responses were reflected by a significant decrease in parameters of growth and yield when salinity reached 8 g.l-1. Indeed, a reduction in the photosynthetic gaseous exchange and a stomata resistance were notified for seedlings subjected to 6 and 8 g.l-1 NaCl treatments. However, in order to tolerate the highest levels of salt, Tossa jute seedlings make different strategies by reducing the size of leaves, which increases their accumulation of osmolytes such as proline (3.1 mg.g-1 DM) and soluble sugars (13.22 µg.g-1 FM) to permitting the osmotic adjustment. -

Pollination and Breeding System of Melochia Tomentosa L

ARTICLE IN PRESS Flora ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]] www.elsevier.de/flora Pollination and breeding system of Melochia tomentosa L. (Malvaceae), a keystone floral resource in the Brazilian Caatinga Isabel Cristina Machadoa,Ã, Marlies Sazimab aDepartamento de Botaˆnica, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, 50232-970 Recife, PE, Brazil bDepartamento de Botaˆnica, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 13.081-970 Campinas, SP, Brazil Received 10 August 2007; accepted 25 September 2007 Abstract The main goals of the present paper were to investigate the floral biology and the breeding system of Melochia tomentosa in a semi-arid region in Brazil, comparing the role of Apis mellifera with other native pollinators, and to discuss the importance of this plant species as a floral resource for the local fauna in maintaining different guilds of specialized pollinators in the Caatinga. M. tomentosa is very common in Caatinga areas and blooms year-round with two flowering peaks, one in the wet and another in the dry period. The pink, bright-colored flowers are distylous and both morphs are homogamous. The trichomatic nectary is located on the inner surface of the connate sepals, and the nectar (ca. 7 ml) is accumulated in the space between the corolla and the calyx. Nectar sugar concentration reaches an average of 28%. The results of controlled pollination experiments show that M. tomentosa is self-incompatible. Pollen viability varies from 94% to 98%. In spite of being visited by several pollen vectors, flower attributes of M. tomentosa point to melittophily, and A. mellifera was the most frequent visitor and the principal pollinator. Although honeybees are exotic, severely competing with native pollinators, they are important together with other native bees, like Centris and Xylocopa species, for the fruit set of M. -

Butterflies of Citrus County and Host Plants

Butterflies of Citrus County ~---4- --•;... ____ - Family I Species Host plant Hesperiidae SkipQers Phocides Qigmalion Mangrove Skipper ~mangrove herbs, vines, shrubs, and trees in the pea family (Fabaceae) including false indigobush (Amorpha fruticosa L.), American hogpeanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata [L.) Fernald), Atlantic pidgeonwings or butterfly pea (Clitoria mariana L.), groundnut (Apios ~vreus clarus Silver-spotted Skip~ americana Medik.), American wisteria (Wisteria frutescens [L.) Poir.) and the introduced Dixie ticktrefoil (Desmodium tortuosum [Sw.] DC.), kudzu (Pueraria montana [Lour.] Merr.), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.), Chinese wisteria (Wisteria sinensis [Sims) DC.) and a variety of other legumes Urbanus prqJg_µs Long-t~.Ued SkiQpec vine legumes including various beans (Phaseolus), hog peanuts (Amphicarpa bracteata), beggar's ticks (Desmodium), blue peas (Clitoria), and wisteria (Wisteria) Various legumes inclu ding wild and cu ltivated beans (Phaseolus), begga r's ticks Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail (Desmodium), and bl ue peas (Clit oria ) -· Beggar\'s ticks (Desmodium); occasionally false indigo (Baptisia) and bush clover Achalarus ly-ciades Hoar.y_r;_ggg {Lespedeza); all in the pea family {Fabaceae) - pea family (Fabaceae) including beggar's ticks (Desmodium), bush clover (Lespedeza), Thor'lbes P'llades Northern Cloud'lwing clover (Trifolium), lotus (Hosackia), and others. -----· Thory-bes bathy-llus Southern Cloudywing Potato bean, Apios americana. Ozark milkvetch, Astragalus distortus var. engelmanni ~ ---- Lespedezas (Lespedeza spp .) are reported as well as Florida Hoarypea (Tephrosia l ibQr:_y_bes confusis Confused Cloudy-wing florid a) . -· -- -------- Staphy:lus hayhurst_ii Ha yh u r?J?-5.IAJ.\QQ Wi ri_g Lambsquart ers {Che nopodium) in the goosefoot family (Chenopodiaceae ), and occasiona lly chaff flower (Alternanthera) in the pigweed family (Amaranthaceae). -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/07/2021 08:53:11AM Via Free Access 130 IAWA Journal, Vol

IAWA Journal, Vol. 27 (2), 2006: 129–136 WOOD ANATOMY OF CRAIGIA (MALVALES) FROM SOUTHEASTERN YUNNAN, CHINA Steven R. Manchester1, Zhiduan Chen2 and Zhekun Zhou3 SUMMARY Wood anatomy of Craigia W.W. Sm. & W.E. Evans (Malvaceae s.l.), a tree endemic to China and Vietnam, is described in order to provide new characters for assessing its affinities relative to other malvalean genera. Craigia has very low-density wood, with abundant diffuse-in-aggre- gate axial parenchyma and tile cells of the Pterospermum type in the multiseriate rays. Although Craigia is distinct from Tilia by the pres- ence of tile cells, they share the feature of helically thickened vessels – supportive of the sister group status suggested for these two genera by other morphological characters and preliminary molecular data. Although Craigia is well represented in the fossil record based on fruits, we were unable to locate fossil woods corresponding in anatomy to that of the extant genus. Key words: Craigia, Tilia, Malvaceae, wood anatomy, tile cells. INTRODUCTION The genus Craigia is endemic to eastern Asia today, with two species in southern China, one of which also extends into northern Vietnam and southeastern Tibet. The genus was initially placed in Sterculiaceae (Smith & Evans 1921; Hsue 1975), then Tiliaceae (Ren 1989; Ying et al. 1993), and more recently in the broadly circumscribed Malvaceae s.l. (including Sterculiaceae, Tiliaceae, and Bombacaceae) (Judd & Manchester 1997; Alverson et al. 1999; Kubitzki & Bayer 2003). Similarities in pollen morphology and staminodes (Judd & Manchester 1997), and chloroplast gene sequence data (Alverson et al. 1999) have suggested a sister relationship to Tilia. -

Melochia Corchorifolia (Redweed)

Australia/New Zealand Weed Risk Assessment adapted for Florida. Data used for analysis published in: Gordon, D.R., D.A. Onderdonk, A.M. Fox, R.K. Stocker, and C. Gantz. 2008. Predicting Invasive Plants in Florida using the Australian Weed Risk Assessment. Invasive Plant Science and Management 1: 178-195. Melochia corchorifolia (redweed) Question number Question Answer Score 1.01 Is the species highly domesticated? n 0 1.02 Has the species become naturalised where grown? 1.03 Does the species have weedy races? 2.01 Species suited to Florida's USDA climate zones (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) 2 2.02 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) 2 2.03 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) 2.04 Native or naturalized in habitats with periodic inundation y 1 2.05 Does the species have a history of repeated introductions outside its natural y range? 3.01 Naturalized beyond native range y 0 3.02 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed y 0 3.03 Weed of agriculture y 0 3.04 Environmental weed n 0 3.05 Congeneric weed y 0 4.01 Produces spines, thorns or burrs n 0 4.02 Allelopathic n 0 4.03 Parasitic n 0 4.04 Unpalatable to grazing animals 4.05 Toxic to animals n 0 4.06 Host for recognised pests and pathogens y 1 4.07 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans n 0 4.08 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems n 0 4.09 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle n? 0 4.1 Grows on infertile soils (oligotrophic, limerock, or excessively draining soils) y 1 4.11 Climbing or smothering growth habit n 0 4.12 -

Conservation of the Arogos Skipper, Atrytone Arogos Arogos (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) in Florida Marc C

Conservation of the Arogos Skipper, Atrytone arogos arogos (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) in Florida Marc C. Minno St. Johns River Water Management District P.O. Box 1429, Palatka, FL 32177 [email protected] Maria Minno Eco-Cognizant, Inc., 600 NW 35th Terrace, Gainesville, FL 32607 [email protected] ABSTRACT The Arogos skipper is a rare and declining butterfly found in native grassland habitats in the eastern and mid- western United States. Five distinct populations of the butterfly occur in specific parts of the range. Atrytone arogos arogos once occurred from southern South Carolina through eastern Georgia and peninsular Florida as far south as Miami. This butterfly is currently thought to be extirpated from South Carolina and Georgia. The six known sites in Florida for A. arogos arogos are public lands with dry prairie or longleaf pine savanna having an abundance of the larval host grass, Sorghastrum secundum. Colonies of the butterfly are threat- ened by catastrophic events such as wild fires, land management activities or no management, and the loss of genetic integrity. The dry prairie preserves of central Florida will be especially important to the recovery of the butterfly, since these are some of the largest and last remaining grasslands in the state. It may be possible to create new colonies of the Arogos skipper by releasing wild-caught females or captive-bred individuals into currently unoccupied areas of high quality habitat. INTRODUCTION tered colonies were found in New Jersey, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, and Mississippi. The three re- gions where the butterfly was most abundant included The Arogos skipper (Atrytone arogos) is a very locally the New Jersey pine barrens, peninsular Florida, and distributed butterfly that occurs only in the eastern and southeastern Mississippi. -

BUTTERFLIES in Thewest Indies of the Caribbean

PO Box 9021, Wilmington, DE 19809, USA E-mail: [email protected]@focusonnature.com Phone: Toll-free in USA 1-888-721-3555 oror 302/529-1876302/529-1876 BUTTERFLIES and MOTHS in the West Indies of the Caribbean in Antigua and Barbuda the Bahamas Barbados the Cayman Islands Cuba Dominica the Dominican Republic Guadeloupe Jamaica Montserrat Puerto Rico Saint Lucia Saint Vincent the Virgin Islands and the ABC islands of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curacao Butterflies in the Caribbean exclusively in Trinidad & Tobago are not in this list. Focus On Nature Tours in the Caribbean have been in: January, February, March, April, May, July, and December. Upper right photo: a HISPANIOLAN KING, Anetia jaegeri, photographed during the FONT tour in the Dominican Republic in February 2012. The genus is nearly entirely in West Indian islands, the species is nearly restricted to Hispaniola. This list of Butterflies of the West Indies compiled by Armas Hill Among the butterfly groupings in this list, links to: Swallowtails: family PAPILIONIDAE with the genera: Battus, Papilio, Parides Whites, Yellows, Sulphurs: family PIERIDAE Mimic-whites: subfamily DISMORPHIINAE with the genus: Dismorphia Subfamily PIERINAE withwith thethe genera:genera: Ascia,Ascia, Ganyra,Ganyra, Glutophrissa,Glutophrissa, MeleteMelete Subfamily COLIADINAE with the genera: Abaeis, Anteos, Aphrissa, Eurema, Kricogonia, Nathalis, Phoebis, Pyrisitia, Zerene Gossamer Wings: family LYCAENIDAE Hairstreaks: subfamily THECLINAE with the genera: Allosmaitia, Calycopis, Chlorostrymon, Cyanophrys, -

Obdiplostemony: the Occurrence of a Transitional Stage Linking Robust Flower Configurations

Annals of Botany 117: 709–724, 2016 doi:10.1093/aob/mcw017, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org VIEWPOINT: PART OF A SPECIAL ISSUE ON DEVELOPMENTAL ROBUSTNESS AND SPECIES DIVERSITY Obdiplostemony: the occurrence of a transitional stage linking robust flower configurations Louis Ronse De Craene1* and Kester Bull-Herenu~ 2,3,4 1Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2Departamento de Ecologıa, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, 3 4 Santiago, Chile, Escuela de Pedagogıa en Biologıa y Ciencias, Universidad Central de Chile and Fundacion Flores, Ministro Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/aob/article/117/5/709/1742492 by guest on 24 December 2020 Carvajal 30, Santiago, Chile * For correspondence. E-mail [email protected] Received: 17 July 2015 Returned for revision: 1 September 2015 Accepted: 23 December 2015 Published electronically: 24 March 2016 Background and Aims Obdiplostemony has long been a controversial condition as it diverges from diploste- mony found among most core eudicot orders by the more external insertion of the alternisepalous stamens. In this paper we review the definition and occurrence of obdiplostemony, and analyse how the condition has impacted on floral diversification and species evolution. Key Results Obdiplostemony represents an amalgamation of at least five different floral developmental pathways, all of them leading to the external positioning of the alternisepalous stamen whorl within a two-whorled androe- cium. In secondary obdiplostemony the antesepalous stamens arise before the alternisepalous stamens. The position of alternisepalous stamens at maturity is more external due to subtle shifts of stamens linked to a weakening of the alternisepalous sector including stamen and petal (type I), alternisepalous stamens arising de facto externally of antesepalous stamens (type II) or alternisepalous stamens shifting outside due to the sterilization of antesepalous sta- mens (type III: Sapotaceae).