In the Matter of an Inquest Touching Upon the Death of Mr Joseph Parker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skyline Orchestras

PRESENTS… SKYLINE Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, you’ll be viewing the band Skyline, led by Ross Kash. Skyline has been performing successfully in the wedding industry for over 10 years. Their experience and professionalism will ensure a great party and a memorable occasion for you and your guests. In addition to the music you’ll be hearing tonight, we’ve supplied a song playlist for your convenience. The list is just a part of what the band has done at prior affairs. If you don’t see your favorite songs listed, please ask. Every concern and detail for your musical tastes will be held in the highest regard. Please inquire regarding the many options available. Skyline Members: • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES…………………………..…….…ROSS KASH • VOCALS……..……………………….……………………………….….BRIDGET SCHLEIER • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..………….…………………….……VINCENT FONTANETTA • GUITAR………………………………….………………………………..…….JOHN HERRITT • SAXOPHONE AND FLUTE……………………..…………..………………DAN GIACOMINI • DRUMS, PERCUSSION AND VOCALS……………………………….…JOEY ANDERSON • BASS GUITAR, VOCALS AND UKULELE………………….……….………TOM MCGUIRE • TRUMPET…….………………………………………………………LEE SCHAARSCHMIDT • TROMBONE……………………………………………………………………..TIM CASSERA • ALTO SAX AND CLARINET………………………………………..ANTHONY POMPPNION www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 DANCE: 24K — BRUNO MARS A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY — FERGIE A SKY FULL OF STARS — COLD PLAY LONELY BOY — BLACK KEYS AIN’T IT FUN — PARAMORE LOVE AND MEMORIES — O.A.R. ALL ABOUT THAT BASS — MEGHAN TRAINOR LOVE ON TOP — BEYONCE BAD ROMANCE — LADY GAGA MANGO TREE — ZAC BROWN BAND BANG BANG — JESSIE J, ARIANA GRANDE & NIKKI MARRY YOU — BRUNO MARS MINAJ MOVES LIKE JAGGER — MAROON 5 BE MY FOREVER — CHRISTINA PERRI FT. ED SHEERAN MR. SAXOBEAT — ALEXANDRA STAN BEST DAY OF MY LIFE — AMERICAN AUTHORS NO EXCUSES — MEGHAN TRAINOR BETTER PLACE — RACHEL PLATTEN NOTHING HOLDING ME BACK — SHAWN MENDES BLOW — KE$HA ON THE FLOOR — J. -

One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and Their Fans

One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and their Fans Annie Lyons TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin December 2020 __________________________________________ Renita Coleman Department of Journalism Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Hannah Lewis Department of Musicology Second Reader 2 ABSTRACT Author: Annie Lyons Title: One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and their Fans Supervising Professors: Renita Coleman, Ph.D. Hannah Lewis, Ph.D. Boy bands have long been disparaged in music journalism settings, largely in part to their close association with hordes of screaming teenage and prepubescent girls. As rock journalism evolved in the 1960s and 1970s, so did two dismissive and misogynistic stereotypes about female fans: groupies and teenyboppers (Coates, 2003). While groupies were scorned in rock circles for their perceived hypersexuality, teenyboppers, who we can consider an umbrella term including boy band fanbases, were defined by a lack of sexuality and viewed as shallow, immature and prone to hysteria, and ridiculed as hall markers of bad taste, despite being driving forces in commercial markets (Ewens, 2020; Sherman, 2020). Similarly, boy bands have been disdained for their perceived femininity and viewed as inauthentic compared to “real” artists— namely, hypermasculine male rock artists. While the boy band genre has evolved and experienced different eras, depictions of both the bands and their fans have stagnated in media, relying on these old stereotypes (Duffett, 2012). This paper aimed to investigate to what extent modern boy bands are portrayed differently from non-boy bands in music journalism through a quantitative content analysis coding articles for certain tropes and themes. -

The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: the Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair', Edinburgh Law Review, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School Citation for published version: Cairns, JW 2007, 'The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: The Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair', Edinburgh Law Review, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 300-48. https://doi.org/10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Edinburgh Law Review Publisher Rights Statement: ©Cairns, J. (2007). The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: The Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair. Edinburgh Law Review, 11, 300-48doi: 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 EdinLR Vol 11 pp 300-348 The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: the Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair John W Cairns* A. INTRODUCTION B. EARLIER VIEWS ON THE FOUNDING OF THE CHAIR C. -

Contemporary

C O N T E M P O R A R Y R E P E R T O I R E f o r S T R I N G Q U A R T E T O N L Y A Hard Day’s Night (The Beatles) Diamonds Are Forever (Shirley Bassey) A Thousand Years (Christina Perri) Disarm (Smashing Pumpkins) Ain't No Mountain High Enough (Marvin Gaye) Don't Stop Believing (Journey) All About That Bass (Meghan Trainor) Don't You Forget About Me (Simple Minds) All Day and All Of The Night (The Kinks) Drive By (Train) All Fall Down (OneRepublic) Edelweiss All of Me (John Legend) Elastic heart (Sia) All My Love (Led Zeppelin) Eleanor Rigby (The Beatles) All You Need is Love (The Beatles) Electric Feel (MGMT) Angel (Sarah McLachlan) Endless Love (Lionel Ritchie) Arrival of the Birds (Cinematic Orchestra) Et Si Tu N'Existais Pas (Joe Dassin) At Last (as performed by Etta James) Every Breath You Take (The Police) Bad Blood (Bastille) Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic (The Police) Bad Romance (Lady Gaga) Every Teardrop is a Waterfall (Coldplay) Beat It (Michael Jackson) Everybody Talks (Neon Trees) Beautiful Day (U2) Fields of Gold (Sting) Begin Again (Taylor Swift) Five Years (David Bowie) Besame Mucho For Your Eyes Only (Sheena Easton) Billie Jean (Michael Jackson) Forget You (CeeLo Green) Billy Joel medley of songs From This Moment On (Shania Twain) (Pressure, Vienna, Uptown Girl, Just The Way You Are, Piano Man) Get Lucky (Daft Punk) Bittersweet Symphony (The Verve) Girls Just Wanna Have Fun (Cyndi Lauper) Black Hole Sun (Soundgarden) Glad You Came (The Wanted) Bleeding Love (Leona Lewis) God Only Knows (Beach Boys) Bohemian Rhapsody -

The Sherwood Crier the Insider Newsletter of Sherwood Forest Faire Welcome to Our Thanksgiving Edition!

The Sherwood Crier The Insider Newsletter of Sherwood Forest Faire Welcome to our Thanksgiving edition! What’s Inside? What’s Inside? Thankful Thoughts in In the Limelight p.2, Elf ’s Sherwood p.1, Vendor’s Corner p. 4, Dec. Gathering Corner p. 3 , Help Wanted p. 1, Archery Contest p. 4 p. 8 unClassfieds (in blue) Medieval Moments p. 3 throughout Hear Ye! Hear Ye! A Notice of Thankfulness! The Sheriff of Nottingham promises his undying gratitude, at least for the moment, to any and all who assist in the capture of the notorious villain, Robin Hood. December 2-4 Gathering Thankful Thoughts in Sherwood Friday by Mab Middlin 4pm – Campground gates open – come one, come Yes, it’s me again… Mab Middlin, risking life and all to set up your campsites! limb to get the latest and greatest news for our Saturday beloved Sherwood Crier... this time, to learn for 9:00 am – 3:00 pm - Volunteer opportunities what the dwellers of Sherwood Forest are thankful. (picking up limbs, removing stumps, leveling Ah, the life of an embedded reporter. It can be pathways, painting, planting, etc) dangerous, so only the best are chosen (blush). 1:00 pm – 3:00 pm – Job Fair for SWFF vendors 7:00 pm onward - Pot Luck Dinner & Gathering. I enter the woods near the Jerusalem Pub hotfoot Please bring a covered dish to share! The Faire will on the trail of Robin Hood, having heard he is in provide water, soda and we’ll have kegs of beer (you the vicinity. The pub is deserted this early Sunday may wish to BYOB in case that runs out). -

Max George Action, Which Was Announced Last Original Screenplay for American Gibney, Repped by UTA, Will Year and for Which Scott Z

14 Wednesday, September 6, 2017 Wednesday, September 6, 2017 15 @RobertDowneyJr Happy Labor Day, everyone! Hoping all you laborers out there get to take 5 dozen)(or a baker’s today. Los Angeles apper A$AP Rocky is “jealous” of model and his former girlfriend KendallR Jenner’s new beau Blake Griffin. According to a source, A$AP Rocky is aware of Kendall and the basketball Science Fiction The Peace And The player’s relationship and Brand New Panic feels envious of him, reports Neck Deep hollywoodlife.com. “A$AP Rocky is very aware of Los Angeles Kendall and Blake and it honestly Los Angeles eginae Carter, the daughter of does make him a little jealous,” inger Katy Perry and actor Orlando Bloom Rrapper Lil Wayne, had a positive the source said. reunited on the beach over the Labour Day update on the status of her father “He has fun with Kendall, but Sweekend. following his hospitalisation. She says up until now hadn’t really been After being spotted together at the beach in her father is doing fine. obsessed with her or anything. California, the former couple added fuel to \Carter took to Twitter to share the He liked seeing her when it rumours that they are back together. health update, reports dailymail.co.uk. was convenient for both This is the second time in a month that “My dad is doing fine everyone. of them but didn’t make the stars were spotted hanging out since Thanks for the concerns. you guys are her his top priority,” the their March 2017 split. -

Outcome of the Statutory Consultation Process on the Proposal to Establish an Annexe to Kirkliston Primary School at Kirkliston Leisure Centre

Policy and Sustainability Committee 10.00am, Thursday, 25 June 2020 Outcome of the Statutory Consultation Process on the Proposal to Establish an Annexe to Kirkliston Primary School at Kirkliston Leisure Centre Executive/routine Executive Wards Almond Council Commitments 28 1. Recommendations 1.1 Approve the proposal to establish an annexe to Kirkliston Primary School at Kirkliston Leisure Centre. Alistair Gaw Executive Director of Communities and Families Contact: Robbie Crockatt, Learning Estate Planning Manager E-mail: [email protected] | Tel: 0131 469 3051 2. Executive Summary 2.1 On 8 October 2019 the Education, Children and Families Committee approved that a statutory consultation be undertaken on the proposal to establish an annexe of Kirkliston Primary School on the Kirkliston Leisure Centre site. The annexe is required to address accommodation pressure at the school caused by rising P1 intakes linked to housing growth around Kirkliston. Following the consultation, this report recommends the proposal, as set out in the statutory consultation paper, is progressed. 3. Background 3.1 On 8 October 2019 the Education, Children and Families Committee approved a statutory consultation to be undertaken on the proposal to establish an annexe of Kirkliston Primary School on the Kirkliston Leisure Centre site. 3.2 In summary, the statutory consultation paper proposed the following: • Establish an annexe for P1, alongside a new early learning and childcare setting, and P2 at a future date, if required; • No changes to primary or secondary school catchment areas are proposed. 3.3 The annexe could open in August 2022 at the earliest, subject to obtaining necessary consents and easing of the current restrictions affecting workplaces and construction sites because of the Coronavirus pandemic. -

The Wanted All Time Low 320

The wanted all time low 320 Free The Wanted All Time Low Capital FM Summertime Ball mp3. Play & Download Size MB ~ ~ kbps. Free The Wanted All Time Low. Download the wanted all time low mp3 songs kbps album listen. The Wanted - All Time Low with lyrics - Duration: IssiieH 3,, views · · Pirate's Progress. Nhạc Việt miễn phí All Time Low hot nhất năm với chất lượng cao, tải nhạc All Time Low mp3. All Time Low The Wanted Tải bài hát All Time Low mp3 chất lượng - Tải download nhạc chờ Time Bomb, All Time Low. Descargar discografia de The Wanted completa totalmente gratis sin fue “All Time Low” que salió a la venta en Reino Unido en julio de Rating: ❺❺❺❺❺ Free download all time low torrent. 28, The Wanted - All Time Low { kbs } , MB, 1, 0, -. 29, All Time. "All Time Low" is a song by British-Irish boy band The Wanted, written by Steve Mac, Wayne Hector and Ed Drewett. It was released on 25 July as the. Stream THE WANTED- All Time Low (D.O.N.S. Club Mix) by DONSdj from desktop or your mobile device. Watch All Time Low by The Wanted online at Discover the latest music videos by The Wanted on Vevo. Buscar y descargar canciones All Time Low Audio The Wanted MP3 gratis. Disfruta bajando Com | Duración: | File size: MB | Kbps. PLAY. All. Descargar All Time Low The Wanted música gratis en Mimp3. Todos los MP3 en alta calidad Kbps (VBR) para descargar. Ofrecemos actualmente los. The Wanted - All Time Low - tekst piosenki, tłumaczenie piosenki i teledysk. -

1 16 Elkland Road ** DANCE MUSIC/ TOP 40 ** HEY HO – THE

16 Elkland Road Melville, NY 11747 631-643-2561 631-643-2563 Fax www.CreationsMusic.com ** DANCE MUSIC/ TOP 40 ** HEY HO – THE LUMINEERS CLARITY - ZEDD GET LUCKY – DAFT PUNK FEAT. PHARRELL I WILL WAIT – MUMFORD & SONS (RED ROCKS VERSION) LITTLE TALKS – OF MONSTERS AND MEN FEEL THIS MOMENT – PITBULL FEAT. CHRISTINA AGUILERA DIAMONDS – RIHANNA STAY - RIHANNA HOME – PHILLIP PHILLIPS DIE YOUNG – KESHA GIRL ON FIRE –ALICIA KEYS DAYLIGHT – MAROON 5 DRIVE BY- TRAIN THE A TEAM – ED SHEERAN LOCKED OUT OF HEAVEN – BRUNO MARS DON’T YOU WORRY CHILD – SWEEDISH HOUSE MAFIA SWEET NOTHING – CALVIN HARRIS/FLORENCE WELCH JUST GIVE ME A REASON – PINK FEAT. FUN CALL ME MAYBE – CARLY RAE JEPSEN GLAD YOU CAME – THE WANTED GOTYE – SOMEBODY THAT I USED TO KNOW TITANIUM – DAVID GUETTA & SIA WILD ONES – SIA/FLO-RIDA FEEL SO CLOSE – CALVIN HARRIS TURN ME ON – NIKKI MINAJ MR. SAXOBEAT – ALEXANDRA STAN GOOD LIFE – ONE REPUBLIC PITBULL/NE-YO – GIVE ME EVERYTHING SOMEONE LIKE YOU – ADELE MOVES LIKE JAGGER – MAROON 5 ONE MORE NIGHT – MAROON 5 DEV- DANCING IN THE DARK PUMPED UP KICKS – FOSTER THE PEOPLE 1 SET FIRE TO THE RAIN – ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP – ADELE SOMEONE LIKE YOU – ADELE TURNING TABLES - ADELE FORGET YOU – CEE LO GREEN PARTY ROCK - LMFAO CLUB CANT HANDLE ME – FLO RIDA IN THE DARK - DEV ON THE FLOOR – JLO & PITBULL GRENADE – BRUNO MARS JUST THE WAY YOU ARE – BRUNO MARS VALERI- AMY WINEHOUSE WILL YOU STILL LOVE ME – AMY WINEHOUSE O.M.G – USHER RAISE YOUR GLASS – PINK LOVE THE WAY YOU LIE – EMINEM & RIHANNA NEED YOU NOW – LADY ANTEBELLUM STEREO LOVE – EDWARD MAYA I GOT A FEELING – BLACK EYED PEAS WE FOUND LOVE –RIHANNA ONLY GIRL IN THE WORLD – RIHANNA S & M – RIHANNA DON’T STOP THE MUSIC – RIHANNA MEET ME HALFWAY – BLACK EYED PEAS EMPIRE STATE – JAY Z / ALICIA KEYS CALIFORNIA GIRLS – KATY PERY TEENAGE DREAM – KATY PERRY T.G.I.F. -

Im Glad U Came

Im glad u came click here to download "Glad You Came" is a song by British-Irish boy band The Wanted, taken as the second single 'My universe will never be the same/ I'm glad you came,' they croon on the outro. The result is their catchiest effort since 'All Time Low', though on. Glad You Came Lyrics: The sun goes down, the stars come out / And all that counts is here and now / My universe will never be the same / I'm glad you came . Glad You Came Lyrics: The sun goes down / The stars come out / And all that counts / Is here and now / My universe will never be the same / I'm glad you came . The sun goes down. The stars come out. And all that counts. Is here and now. My universe will never be the same. I'm glad you came. You cast a spell on me. glad you came is the very good single released by the wanted in It is off their second album and I'm glad you came. I'm glad you came. The Wanted - Glad You Came (Letra e música para ouvir) - And all that counts / Is here and now / My universe / Will never be the same / I'm glad you came. The sun goes down / The stars come out / And all that counts / Is here and now / My universe will never be the same / I'm glad you came / You cast a spell on me, . Sebastian: The sun goes down, The stars come out, And all that counts, Is here and now, My universe will never be the same, I'm glad you came, Sebastian with . -

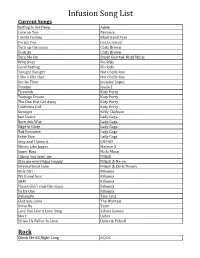

Infusion Song List

Infusion Song List Current Songs Rolling In the Deep Adele Love on Top Beyonce I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Forget You Cee Lo Green Turn up the music Chris Brown Yeah 3x Chris Brown Turn Me On David Guetta& Nicki Minaj Wild Ones Flo Rida Good Feeling Flo Rida Tonight Tonight Hot Chelle Rae I like it like that Hot Chelle Rae On the Floor Jennifer Lopez Domino Jessie J Firework Katy Perry Teenage Dream Katy Perry The One that Got Away Katy Perry California Girl Katy Perry Stronger Kelly Clarkson Just Dance Lady Gaga Born this Way Lady Gaga Edge of Glory Lady Gaga Bad Romance Lady Gaga Poker Face Lady Gaga Sexy and I know it LMFAO Moves Like Jagger Maroon 5 Super Bass Nicki Minaj I know you want me Pitbull Give me everything tonight Pitbull & Ne-yo International Love Pitbull & Chris Brown Only Girl Rihanna We found love Rihanna S&M Rihanna Please don't stop the music Rihanna Ya Da One Rihanna Dynamite Taio Cruz Glad you came The Wanted Drive By Train Love You Like a Love Song Selena Gomez More Usher DJ Got Us Fallin' In Love Usher & Pitbull Rock Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC Infusion Song List Living on a Prayer Bon Jovi Don't Stop Believin' Journey Separate Ways Journey Anyway you want it Journey Proud Mary Tina Turner Simply the Best Tina Turner Back in Black AC/DC Motown/Oldie But Goodie Let's Stay Together Al Green Chain of Fools Aretha Franklin Respect Aretha Franklin Think Aretha Franklin Long Train Runnin' Doobie Brothers September Earth, Wind & Fire Let's Groove Earth, Wind & Fire Boogie Wonderland Earth, Wind & Fire Anit no mountainhigh -

Murphy James Acoustic Guitarist/Singer M: 07944415436 E

Murphy James Acoustic Guitarist/Singer M: 07944415436 E: [email protected] W: www.MurphyJames.live Murphy knows over 2000+ covers. Here is sample list of a few songs but there are many more that aren't on this list so please feel free to request anything else. If Murphy knows it, he will be sure to play it for you. Song list 20th Century Boy – T-Rex 500 miles – The Proclaimers A little respect – Erasure/Wheatus A sky full of stars - Coldplay A thousand years – Christina Peri Africa - Toto Ain't no sunshine – Bill Withers Ain’t nobody – Chaka Khan Alcoholic – Starsailor All about you - McFly All I want is you – U2 All night long – Lionel Richie All of me – John Legend All the small things – Blink 182 All time low – The Wanted Always on my mind – Elvis Presley America – Razorlight America – Neil Diamond American Pie – Don McClean Am I wrong – Nico & Vinz Angel of Harlem – U2 Angels – Robbie Williams Another brick in the wall – Pink Floyd Another day in Paradise – Phil Collins Apologize – One Republic Ashes – Embrace A sky full of stars - Coldplay A-team - Ed Sheeran Baby can I hold you – Tracy Chapman Baby one more time – Britney Spears Babylon – David Gray Back for good – Take That Back to black – Amy Winehouse Bad moon rising – Credence Clearwater Revival Be mine – David Gray Be my baby – The Ronettes Beautiful noise – Neil Diamond Beautiful war – Kings of Leon Best of you – Foo Fighters Better – Tom Baxter Big love – Fleetwood Mac Big yellow taxi – Joni Mitchell Black and gold – Sam Sparrow Black is the colour – Christie Moore