15 Sutherland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethno Thierry 2003 432.Pdf Pdf 1 Mo

SOMMAIRE I NTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 3 L A PROBLÉMATIQUE : DE NOUVEAUX TERRITOIRES, LES PAYS .............................................................. 3 O BJECTIFS DE L’ÉTUDE ................................................................................................................. 5 C HOIX DU TERRAIN ...................................................................................................................... 5 M ÉTHODE DE RECHERCHE ............................................................................................................. 6 1. CARACTÉRISTIQUES PRINCIPALES DU PAYS AUTUNOIS-MORVAN ............... 6 1.1. LA POLITIQUE DE PAYS AU SEIN DE LA RÉGION BOURGOGNE ....................................................... 6 1.2. CONSTITUTION DU PAYS AUTUNOIS-MORVAN ......................................................................... 7 2. INVENTAIRE PATRIMONIAL ET MODE DE VALORISATION .............................. 9 2.1. DESCRIPTIF ........................................................................................................................ 10 2.1.1. Le patrimoine monumental et archéologique de l’Autunois-Morvan ..................... 10 2.1.2. Le patrimoine antique : de Bibracte à Augustodunum ........................................... 12 2.1.3. Le patrimoine médiéval : la Cathédrale ................................................................. 13 2.1.4. La Société Eduenne ................................................................................................ -

Liste Des Communes Ou La Presence De Castors Est

LISTE DES COMMUNES OU LA PRESENCE DE CASTORS EST AVEREE L'ABERGEMENT-DE-CUISERY CIEL LAIZY PONTOUX SAUNIERES ALLEREY-SUR-SAONE CLERMAIN LAYS-SUR-LE-DOUBS PRETY SAVIGNY-SUR-GROSNE ALLERIOT CLUNY LESME RANCY SAVIGNY-SUR-SEILLE AMEUGNY CONDAL LOISY RATENELLE LA CELLE-EN-MORVAN ANZY-LE-DUC CORDESSE LONGEPIERRE RIGNY-SUR-ARROUX SOMMANT ARTAIX CORMATIN LOUHANS ROMANECHE-THORINS SORNAY AUTUN CORTAMBERT LOURNAND SAINT-AGNAN SULLY BANTANGES CRECHES-SUR-SAONE LUCENAY-L'EVEQUE SAINT-ALBAIN TAIZE BARNAY CRESSY-SUR-SOMME LUGNY-LES-CHAROLLES SAINT-AUBIN-SUR-LOIRE TAVERNAY BAUGY CRISSEY LUX SAINTE-CECILE THIL-SUR-ARROUX BEY CRONAT MACON SAINTE-CROIX SENOZAN LES BORDES CUISERY MALAY SAINT-DIDIER-EN-BRIONNAIS SERCY LA BOULAYE DAMEREY MALTAT SAINT-DIDIER-SUR-ARROUX SERMESSE BOURBON-LANCY DIGOIN MARCIGNY SAINT-EDMOND SIMANDRE BOURG-LE-COMTE DOMMARTIN-LES-CUISEAUX MARLY-SOUS-ISSY SAINT-FORGEOT TINTRY BOYER DRACY-SAINT-LOUP MARNAY SAINT-GENGOUX-LE-NATIONAL TOULON-SUR-ARROUX BRAGNY-SUR-SAONE ECUELLES MASSILLY SAINT-GERMAIN-DU-PLAIN TOURNUS BRANDON EPERVANS MAZILLE SAINT-JULIEN-DE-CIVRY TRAMBLY BRANGES EPINAC MELAY SAINT-LEGER-DU-BOIS LA TRUCHERE BRAY ETANG-SUR-ARROUX MESSEY-SUR-GROSNE SAINT-LEGER-LES-PARAY UCHIZY BRIENNE FARGES-LES-MACON MESVRES SAINT-LEGER-SOUS-LA-BUSSIERE UXEAU BRION FRETTERANS MONTAGNY-SUR-GROSNE SAINT-LOUP-DE-VARENNES VARENNE-L'ARCONCE BRUAILLES FRONTENARD MONTBELLET SAINT-MARCEL VARENNES-LE-GRAND CHALON-SUR-SAONE FRONTENAUD MONTCEAUX-L'ETOILE SAINT-MARTIN-BELLE-ROCHE VARENNES-LES-MACON CHAMBILLY LA GENETE MONTHELON SAINT-MARTIN-DE-LIXY -

Departement De Saone-Et-Loire Nombre D'emplacements D'affichage Electoral Arrondissement De Charolles

DEPARTEMENT DE SAONE-ET-LOIRE NOMBRE D'EMPLACEMENTS D'AFFICHAGE ELECTORAL ARRONDISSEMENT D'AUTUN CANTON COMMUNES ADRESSE Bureau de vote groupe scolaire du Clos-Jovet : façade - CANTON D'AUTUN-NORD AUTUN 13 de l'école Av. République, mur gymnase rue Rolin Av. République, entrée quai gare Rue de la Barre - rue des Gailles : terrain ville situé au croisement de ces deux deux Rue du 11 novembre 18, près voie ferrée BV groupe scolaire Parc St-Andoche : mur de clôture de la caserne pompiers, jouxtant celui du groupe scolaire (St Pantaléon) BV du groupe scolaire Victor-Hugo : mur de l'école Mairie annexe, mur cimetière, parallèle à l'avenue de (St Pantaléon) la République (St Pantaléon) Rue Pierre et Marie Curie: prieuré St Martin (St Pantaléon) Route d'Arnay-le-Duc, à la hauteur du n° 24 Route d'Arnay-le-Duc, à la hauteur de l'ancienne (St Pantaléon) gare de l'Orme Rue Antoine Clément : prés de la Place Général (St Pantaléon) Brosset Quartier St-Pierre, angle rues de Bourgogne et de (St Pantaléon) Moirans DRACY-ST-LOUP 1 Place de la mairie MONTHELON 1 le bourg ST-FORGEOT 1 le bourg TAVERNAY 1 le bourg 17 BV hôtel de ville : mur de l'Hotel de ville, côté rue - CANTON D'AUTUN-SUD AUTUN 6 Guérin Rue H. Dunant, muret de la maison verte Rue Victor Terret (à proximité tennis) Place d'Hallencourt, arrière Palais Justice Couhard : sur parking près cabine téléphonique Bureau vote de Fragny, mur du préau de la salle "La communale" ANTULLY 1 le bourg, place de la mairie AUXY 2 parking face au terrain de sports D298 CD 278 " la petite auberge" (21 route -

Bureaux De L'enregistrement

Bureaux de l'Enregistrement Ancien Régime Début Fin Observations Post Révolution : Début Fin Organisation du 31 mars 1808 Observations Rattachement Contrôle et enregistrement / Direction de Bureau de : l'enregistrement, des domaines et du timbre de Saône-et-Loire / Bureau de : Abergement-Sainte-Colombe (l') 1708 1712 Supprimé en 1712 au profit du bureau de Lessard-en- Bresse. Autun 1698 1837 Autun 1791 1970 Communes du canton d'Autun, Saint- Léger et Mesvres Beaurepaire 1698 1793 Beaurepaire 1791 1926 Communes de ce canton. Bellevesvre 1714 1750 Transféré à Bosjean de 1727 à 1729 et supprimé en 1750 au profit du bureau de Pierre. Bourbon-Lancy 1703 1813 Bourbon-Lancy 1791 1968 Communes de ce canton. Bourgneuf 1728 1753 Supprimé en 1753 au profit du Givry. Brancion 1716 1791 Réuni au bureau de Sennecey-le-Grand de 1758 à 1770. Buxy 1676 1797 Le bureau de Buxy comprend les communes suivantes : Buxy 1791 1967 Communes de ce canton. Bissey-sur-Cruchaud, Bissy-sur-Fley, Buxy, Cersot, Chenôves, Culles-les-Roches, Fley, Germagny, Jully-lès- Buxy, Marcilly-lès-Buxy, Messey-sur-Grosne, Montagny- lès-Buxy, Moroges, Saint-Boil, Saint-Germagny-lès-Buxy, Sainte-Hélène, Saint-Martin-d'Auxy, Saint-Martin-du- Tartre, Saint-Maurice-des-Champs, Saint-Privé, Saint- Vallerin, Santilly, Sassangy, Saules, Savianges, Sercy, Villeneuve-en-Montagne. Chagny 1704 1807 Le bureau de Chagny comprend les communes suivantes Chagny 1791 1967 Communes de ce canton. : Aluze, Bouzeron, Chagny, Chamilly, Chassey-le-Camp, Chaudenay, Demigny, Dennevy, Fontaines, Lessard-le- National, Remigny, Rully, Saint-Gilles, Saint-Léger-sur- Dheune Chalon-sur-Saône 1693 1804 Chalon-sur-Saône 1791 1969 Communes des cantons de Chalon et Comprenait le bureau de Saint- Saint-Germain-du-Plain. -

![Le Registre De La Société Républicaine De Paray-Le-Monial : Généralités Et Singularités in : Les Sociétés Populaires À Travers Leurs Procès-Verbaux [En Ligne]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7630/le-registre-de-la-soci%C3%A9t%C3%A9-r%C3%A9publicaine-de-paray-le-monial-g%C3%A9n%C3%A9ralit%C3%A9s-et-singularit%C3%A9s-in-les-soci%C3%A9t%C3%A9s-populaires-%C3%A0-travers-leurs-proc%C3%A8s-verbaux-en-ligne-687630.webp)

Le Registre De La Société Républicaine De Paray-Le-Monial : Généralités Et Singularités in : Les Sociétés Populaires À Travers Leurs Procès-Verbaux [En Ligne]

Serge Bianchi (dir.) Les sociétés populaires à travers leurs procès-verbaux Éditions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques Le registre de la Société républicaine de Paray-le- Monial : généralités et singularités Bernard Gainot DOI : 10.4000/books.cths.4001 Éditeur : Éditions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques Lieu d'édition : Éditions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques Année d'édition : 2018 Date de mise en ligne : 27 novembre 2018 Collection : Actes des congrès nationaux des sociétés historiques et scientifiques ISBN électronique : 9782735508792 http://books.openedition.org Référence électronique GAINOT, Bernard. Le registre de la Société républicaine de Paray-le-Monial : généralités et singularités In : Les sociétés populaires à travers leurs procès-verbaux [en ligne]. Paris : Éditions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques, 2018 (généré le 20 novembre 2020). Disponible sur Internet : <http:// books.openedition.org/cths/4001>. ISBN : 9782735508792. DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/books.cths. 4001. Le registre de la Société républicaine de Paray-le-Monial : généralités et singularités Bernard Gainot Maître de conférences honoraire à l'Institut d’histoire de la Révolution française, université Paris I – Panthéon-Sorbonne Extrait de : BIANCHI Serge (dir.), Les sociétés populaires à travers leurs procès-verbaux : un réseau de sociabilité politique sous la Révolution française, éd. électronique, Paris, Éd. du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques (Actes des congrès nationaux des sociétés historiques et scientifiques), 2018. Cet article a été validé par le comité de lecture des Éditions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques dans le cadre de la publication des actes du 140e Congrès national des sociétés historiques et scientifiques tenu à Reims en 2015. -

COORDONNEES Service Départemental COORDONNEES Des Professeurs EPS Du District De Paray Le Monial

COORDONNEES Service Départemental Noms Prénoms Tél pers Email Adresse Cité administrative Bd MOURAND Chantal 03 85 22 55 90 [email protected] H.Dunant BP 72512 71025 DIRECTRICE UNSS71 Mâcon cedex 9 Coordonnateur District Clg Saint-Cyr Paray le Monial GRACBLING Frederic 06 89 81 03 62 [email protected] 71520 Matour COORDONNEES Des professeurs EPS du District de paray le monial Etablissement Ville Noms Prénoms Tél pers Email Fonction Adresse clg des Autels Charolles MALOT Joelle [email protected] clg des Autels Charolles 06 74 46 20 76 [email protected] DUCROUX Maxime clg des Autels Charolles 06 64 15 43 34 [email protected] CLEAU Simon clg des Autels Charolles 06 01 20 34 07 [email protected] GUERMAIN Elise clg Ste Marguerite Charolles RONDET Julien 06 30 89 56 79 [email protected] SAS-TAS clg Ste Marguerite Charolles 03 85 50 46 67 clg St Cyr Matour GRACBLING Frédéric SAS Commerçon d'en haut 71520 06 89 81 03 62 [email protected] Dompierre les Ormes. clg St Cyr Matour PELLENARD Jimmy 06 84 18 79 88 [email protected] TAS clg R Cassin Paray le Monial ZUCCHIATTI Jean marc 06 88 97 48 91 TAS 71120 Lugny les charolles 03 85 88 84 19 22 rue du 11 novembre clg R Cassin Paray le Monial BATY Laurence [email protected] 06 86 04 65 60 71600 paray le monial 2 rue Pré des angles clg R Cassin Paray le Monial MAIRET Isabelle 06 88 76 74 61 [email protected] SAS 71600 Paray le Monial clg R Cassin Paray le Monial CABATON Elise 06 63 19 49 71 [email protected] Etablissement Ville Noms Prénoms -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Comite Direction 27/11/2020

DISTRICT SAONE ET LOIRE DE FOOTBALL SECTEURS – SOUS SECTEURS Projet MARS 2021 01/05/2021 DISTRICT SAÔNE ET LOIRE DE FOOTBALL 1 LA SAONE ET LOIRE : EN CHIFFRES Avec une population estimée de 548 000 habitants au 1er janvier 2020, la Saône-et- Loire est le département le plus peuplé de la région Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. Mais la dynamique démographique n'est plus au rendez-vous ; sa population est en baisse depuis 2013 Superficie de 8 574,7 km ² (18 % de la superficie de la Bourgogne Franche Comté) 01/05/2021 DISTRICT SAÔNE ET LOIRE DE FOOTBALL 2 LE DISTRICT : EN CHIFFRES 146 CLUBS 16 998 LICENCIES Base 2020 2021 19 ELUS 6 SALARIES 01/05/2021 DISTRICT SAÔNE ET LOIRE DE FOOTBALL 3 LE DISTRICT : 5 SECTEURS Méthode : Un découpage en se basant sur les arrondissements (source CD71). 5 arrondissements. On intègre AUTUN 1 et 2 dans un secteur tout en se gardant la possibilité de traiter via la sous sectorisation cette partie « isolée » de notre District. Et une sous sectorisation par CANTONS afin de coller au plus près à la politique du territoire. Un sous secteur, un (ou quelques) canton (s), un interlocuteur « politique », une dynamique de territoire. 01/05/2021 DISTRICT SAÔNE ET LOIRE DE FOOTBALL 4 LES 5 ARRONDISSEMENTS 01/05/2021 DISTRICT SAÔNE ET LOIRE DE FOOTBALL 5 LES 25 CANTONS 01/05/2021 DISTRICT SAÔNE ET LOIRE DE FOOTBALL 6 LE DISTRICT : 5 SECTEURS Il faut donner un nom à chaque secteur, associer une Secteur 1: Grand Charolais couleur. Secteur 2: Autunois et CUCM Secteur 3: Mâconnais 1 secteur = deux élus du CD 10 personnes Secteur 4: Chalonnais En charge de trouver un Secteur 5: Bresse 71 réfèrent pour chaque sous secteur (canton). -

“Bonapartism” As Hazard and Promise." Caesarism in the Post-Revolutionary Age

Prutsch, Markus J. "“Bonapartism” as Hazard and Promise." Caesarism in the Post-Revolutionary Age. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020. 47–66. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474267571.ch-003>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 09:26 UTC. Copyright © Markus J. Prutsch 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 3 “ B o n a p a r t i s m ” a s H a z a r d a n d P r o m i s e 3.1 Political Legitimacy in Post-Napoleonic Europe At fi rst glance, the general political situation in Europe seemed to be quite clear in 1814/1815: with Napoleon’s military defeat, the Revolution had fi nally been overpowered, its ideological foundations shattered, and the victorious anti-Napoleonic forces could feel free to turn the clocks back. Practically all over Europe the practice and language of “Revolution” was compromised, and among conservatives and liberals alike the concept of “popular sovereignty” served to denote—and indeed demonize—all the burdens, crises and sacrifi ces Europe had suff ered in the previous quarter of a century. It was hard to fi nd active advocates of radical political, social or economic change; instead, the main discourse of the time was about durable peace, reconstruction, or at most reform. Despite the fact that the partisans of the Revolution were on the defensive, however, hardly anywhere on the continent did restoration policies have the character of pure reaction or a return to pre-revolutionary conditions. -

Mise En Page 1 03/03/2017 15:55 Page1

GUIDE 2017 BAT_Mise en page 1 03/03/2017 15:55 Page1 Culture ou nature ? les deux c’est mieux ! Entre Autun, Ville d’Art et d’Histoire et Morvan, forêts et mystères... Tourist guide Tourist www.autun-tourisme.com Culture or nature? Why not both! From Autun, City of Art and History to Morvan, land of forests and myths… GB GUIDE 2017 BAT_Mise en page 1 03/03/2017 15:55 Page2 Cathédrale Saint-Lazare - Autun Direction ANOST Saulieu ANTULLY Vézelay AUTUN AUXY CChhissey-iissseyy-- BARNAY en-Morvanen-Morrvvvaan BROYE Direction CHARBONNAT Dijon CHISSEY-EN-MORVAN BarnayBarnay Cussy-en-Cussyy--en- COLLONGE-LA-MADELEINE MorvanMorrvvvaan Lucenay-Lucenayy-- CORDESSE AnostAnnost l'Évêquel'Évvêêque CRÉOT SommantSomo mant IgornayIgornay CURGY ReclesneRec CordesseCordesse CUSSY-EN-MORVAN Direction Chateau-Chinon LaLa Petite-Petittee- DETTEY NeverNeversrss VerrièreVVeerrière SSaintSaSaint-Léger Lé Dracy-D ar ccyyy-- dudu-Bois B Roussillon-Roussillon- TTaTavernayavv rna DRACY-SAINT-LOUP en-Morvanen-Morrvvvaan Saint-LoupSaintt--Loup Sully EPERTULLY La Celle-C elle - en-Morvanen-Morrvvvaan Saint-ForgeotSaSSaint-Fa FoForgo ggeoteoeotot EPINAC Haut Folin Epinacpiinn GLUX-EN-GLENNE CCurgyurgy IGORNAY LA BOULAYE Glux-en- MMonthelononthelon SaisyS isyy Glenne LaLa Grande- MorletM ett EpertullyEpertullyrtrtully LA CELLE-EN-MORVAN VVeVerrièreerrrr rèi e AuxyAuxxyy Collonge-laoonge-lala DirectionDirection LA CHAPELLE-SOUS-UCHON Madeleine Beaune TintryiT nttrrryy LA GRANDE-VERRIÈRE BibracteBibracacte AutunAutun Saint-Gervaisiss LAIZY sur-Couchessu heses Saint-Léger--Léger-er -

Mise En Page:1

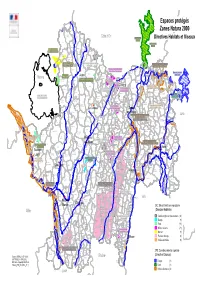

Espaces protégés re Chissey- u en-Morvan C Zones Natura 2000 la Cussy- en-Morvan Lucenay- l'Evêque Côte d'Or Barnay Forêt de Citeaux Directives Habitats et Oiseaux et environs Anost n Forêt de Citeaux i n La Pte- r Igornay et environ Sommant e Verriere T Reclesne Cordesse Hêtraie montagnarde et e l tourbières du Haut Morvan St-Léger- du-Bois Roussillon -en-Morvan Dracy-St La Celle en Tavernay Loup Morvan St- Forgeot Pourlans Forêts, landes, tourbières Gîtes et habitats à chauves-souris Epinac Prairies inondables de la Basse Vallée l'Y Curgy Clux onne de la ValleéLa Gde- de La Canche en BourgogneSully Palleau Verrière duLa DoubsVilleneuve jusqu'a l'amont de Navilly Saisy Ecuelles Mont-les St-Prix Pelouses et forêts calcicoles de la St-Gervais St-Martin- Monthelon Epertully Seurrele (Autun Morlet en-Vallière Doubs Côte et Arrière Côte de Beaune St-Loup- en-Gatinois Longepierre Collonge-la Géanges Charnay-les Lays-s-le Beauvernois en partie Auxy -Madeleine Dezize-les Bragny-s Chalon Navilly Doubs ( partie Ouest) Massif forestier Change Maranges Autun St-Gervais-s Saône Fretterans du Mont Beuvray Tintry Paris Nièvre Couches Demigny Pontoux St-Léger-s/s Forêt de Ravin et landes du Vallon Créot l'Hôpital Saunières St-Martin-de Chaudenay Allerey-s-Saône Charette Beuvray Brion de Canada, barrage du Pont du Roi Remigny Laizy Commune Sampigny ( Les Bordes Varennes St-Sernin les-M Cheilly Chagny Authumes Dracy Sermesse du-Plain Verdun-s Frontenard les-C les-M Bouzeron Antully Chagny le-Doubs Basse vallée du Doubs Mouthier Broye Chassey Gergy en-Bresse -

Charolles 10311- Paray Le Monial - Macon

TRANSPORT SCOLAIRE PAR SECTEUR : CHAROLLES 10311- PARAY LE MONIAL - MACON Service Aller Interne : Point d'arrêt Lundi PARAY-LE-MONIAL - Gare SNCF 07:43 PARAY-LE-MONIAL - LEP Sacré Coeur 07:53 CHAROLLES - Internat de Bourgogne 08:04 CHAROLLES - Rue de Champagny 08:08 BEAUBERY - La Gare 08:13 CURTIL-SOUS-BUFFIERES - Le Bourg 08:44 MAZILLE - Le Bourg 08:51 STE-CECILE - Le Bourg 08:56 STE-CECILE - La Valouze 08:59 CHARNAY-LES-MACON - EREA Gendarmerie 09:11 MACON - Bd des 9 Clés,Collège Bréart 09:12 MACON - Esplanade Dumaine 09:15 MACON - Lycée Lamartine 09:17 * circule uniquement les mercredi de veille de pont Service Retour Interne : Point d'arrêt Vendredi Service Retour Interne : Mercredi * MACON - Gare Routière 18:00 12:50 MACON - Bd Rocca,Collège Pasteur 18:07 12:57 MACON - Lycée Lamartine 18:08 12:58 MACON - Esplanade Dumaine 18:12 13:10 MACON - Bd des 9 Clés,Collège Bréart 18:15 13:13 CHARNAY-LES-MACON - EREA Gendarmerie 18:19 13:17 STE-CECILE - La Valouze 18:35 13:33 STE-CECILE - Le Bourg 18:38 13:36 CURTIL-SOUS-BUFFIERES - Le Bourg 18:49 13:47 CURTIL-SOUS-BUFFIERES - Les Branles 18:55 13:53 BEAUBERY - La Gare 19:00 13:58 CHAROLLES - Rue de Champagny 19:12 14:10 PARAY-LE-MONIAL - LEP Sacré Coeur 19:20 14:18 PARAY-LE-MONIAL - Collège René Cassin 19:25 14:23 PARAY-LE-MONIAL - Gare SNCF 19:33 14:31 40201- MACON - CHAROLLES Service Aller Interne : Point d'arrêt Lundi MACON - Gare Routière 07:20 CLUNY - Ville ( Porte de Paris) 07:53 TRIVY - Chandon 07:59 CHAROLLES - Internat Rue de Bourgogne 08:42 CHAROLLES - Pré Saint Nicolas 08:45 40202