Branch, W.R. 2007. a New Species of Tortoise of the Genus Homopus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Body Condition Assessment – As a Welfare and Management Assessment Tool for Radiated Tortoises (Astrochelys Radiata)

Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management assessment tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Independent project • 15 hp Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU Department of Animal Environment and Health Programme/Education Uppsala 2020 2 Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Supervisor: Lisa Lundin, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Examiner: Maria Andersson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Credits: 15 hp Level: First cycle, G2E Course title: Independent project Course code: EX0894 Programme/education: Course coordinating dept: Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment Place of publication: Uppsala Year of publication: 2020 Cover picture: Linn Lagerström Keywords: Tortoise, turtle, radiated tortoise, Astrochelys radiata, Geochelone radiata, body condition indices, body condition score, morphometrics Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Animal Environment and Health 3 Publishing and archiving Approved students’ theses at SLU are published electronically. As a student, you have the copyright to your own work and need to approve the electronic publishing. If you check the box for YES, the full text (pdf file) and metadata will be visible and searchable online. If you check the box for NO, only the metadata and the abstract will be visiable and searchable online. Nevertheless, when the document is uploaded it will still be archived as a digital file. -

Egyptian Tortoise (Testudo Kleinmanni)

EAZA Reptile Taxon Advisory Group Best Practice Guidelines for the Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) First edition, May 2019 Editors: Mark de Boer, Lotte Jansen & Job Stumpel EAZA Reptile TAG chair: Ivan Rehak, Prague Zoo. EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (May 2019) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA Reptile TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. EAZA Preamble Right from the very beginning it has been the concern of EAZA and the EEPs to encourage and promote the highest possible standards for husbandry of zoo and aquarium animals. -

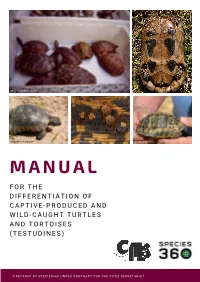

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

A Phylogenomic Analysis of Turtles ⇑ Nicholas G

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 83 (2015) 250–257 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A phylogenomic analysis of turtles ⇑ Nicholas G. Crawford a,b,1, James F. Parham c, ,1, Anna B. Sellas a, Brant C. Faircloth d, Travis C. Glenn e, Theodore J. Papenfuss f, James B. Henderson a, Madison H. Hansen a,g, W. Brian Simison a a Center for Comparative Genomics, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA b Department of Genetics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA c John D. Cooper Archaeological and Paleontological Center, Department of Geological Sciences, California State University, Fullerton, CA 92834, USA d Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA e Department of Environmental Health Science, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA f Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA g Mathematical and Computational Biology Department, Harvey Mudd College, 301 Platt Boulevard, Claremont, CA 9171, USA article info abstract Article history: Molecular analyses of turtle relationships have overturned prevailing morphological hypotheses and Received 11 July 2014 prompted the development of a new taxonomy. Here we provide the first genome-scale analysis of turtle Revised 16 October 2014 phylogeny. We sequenced 2381 ultraconserved element (UCE) loci representing a total of 1,718,154 bp of Accepted 28 October 2014 aligned sequence. Our sampling includes 32 turtle taxa representing all 14 recognized turtle families and Available online 4 November 2014 an additional six outgroups. Maximum likelihood, Bayesian, and species tree methods produce a single resolved phylogeny. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Indian Star Tortoise Care

RVC Exotics Service Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street London NW1 0TU T: 0207 554 3528 F: 0207 388 8124 www.rvc.ac.uk/BSAH INDIAN STAR TORTOISE CARE Indian star tortoises originate from the semi-arid dry grasslands of Indian subcontinent. They can be easily recognised by the distinctive star pattern on their bumpy carapace. Star tortoises are very sensitive to their environmental conditions and so not recommended for novice tortoise owners. It is important to note that these tortoises do not hibernate. HOUSING • Tortoises make poor vivarium subjects. Ideally a floor pen or tortoise table should be created. This needs to have solid sides (1 foot high) for most tortoises. Many are made out of wood or plastic. A large an area as possible should be provided, but as the size increases extra basking sites will need to be provided. For a small juvenile at least 90 cm (3 feet) long x 30 cm (1 foot) wide is recommended. This is required to enable a thermal gradient to be created along the length of the tank (hot to cold). • Hides are required to provide some security. Artificial plants, cardboard boxes, plant pots, logs or commercially available hides can be used. They should be placed both at the warm and cooler ends of the tank. • Substrates suitable for housing tortoises include newspaper, Astroturf, and some of the commercially available substrates. Natural substrate such as soil may also be used to allow for digging. It is important that the substrates either cannot be eaten, or if they are, do not cause blockages as this can prove fatal. -

Aldabrachelys Arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold's Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — AldabrachelysTortoise and Freshwater arnoldi Turtle Specialist Group 028.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.028.arnoldi.v1.2009 © 2009 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 18 October 2009 Aldabrachelys arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold’s Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge CB1 7BX, United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – Arnold’s giant tortoise, Aldabrachelys arnoldi (= Dipsochelys arnoldi) (Family Testudinidae), from the granitic Seychelles, is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tortoise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologi- cally distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered synonymous with that species by many researchers. Captive reared juveniles suggest that there may be a genetic basis for the morphotype and more detailed genetic work is needed to elucidate these relationships. The species is the only living saddle-backed tortoise in the Seychelles islands. It was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and believed to be extinct until recently purportedly rediscovered in captivity. The current population of this morphotype is 23 adults, including 18 captive adult males on Mahé Island, 5 adults recently in- troduced to Silhouette Island, and one free-ranging female on Cousine Island. Successful captive breeding has produced 138 juveniles to date. -

Mitochondrial Genome Reveals Contrasting Pattern of Adaptive

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.18.431795; this version posted February 18, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. MITOCHONDRIAL GENOME REVEALS CONTRASTING PATTERN OF ADAPTIVE SELECTION IN TURTLES AND TORTOISES Subhashree Sahoo1,2, Ajit Kumar1, Jagdish Rai2, Sandeep Kumar Gupta1 1. Department of Animal Ecology and Conservation Biology, Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun 2. Institute of Forensic Science and Criminology, Panjab University, India *Author for correspondence Dr. S.K. Gupta Scientist-E Wildlife Institute of India Dehra Dun 248 001, India E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: +91-135-2646343 Fax No.: +91-135-2640117 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.18.431795; this version posted February 18, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract Testudinoidea represents an evolutionarily unique taxon comprising both turtles and tortoises. The contrasting habitats that turtles and tortoises inhabit are associated with unique physio-ecological challenges hence enable distinct adaptive evolutionary strategies. To comparatively understand the pattern and strength of Darwinian selection and physicochemical evolution in turtle and tortoise mitogenomes, we employed adaptive divergence and selection analyses. We evaluated changes in structural and biochemical properties, and codon models on the mitochondrial protein-coding genes (PCGs) among three turtles and a tortoise lineage. -

Descriptions of Some A.Frican Tortoises

A"nals aftlte Natal Museum. Vol. VI, 1)(1ft 3 DESCRIPTIONS OF SOME AFRICAN TORTOISES. 46 1 Descriptions of some A.frican Tortoises. By John II C\\'itt. With P lates XXXVI-XXXVIII, and 5 Text. fi gul·es. CONTENTS. P elusios s inuatus s inu n.t us Smith J(j2 P elus ios s illu atus zuluensis H elQift 462 P ell1si os ni g r ica. ns n igricnns DonllC/. 4(\3 Pelus ios ni g ri can s castanoides SIIUS)1. n . 4(13 Peil1si os nigr icn.ns ca.stan e us Schw. 464 P elus ios nigricans rh odesianus H ellJi tt 465 Kinixys hellian!} Gray -I n? Kinixys nogll ey i Lataste ·HiS Kin ixys s pekii Gray. 469 Kinixys be lliana. zombensis sllbsp. '11. ·WO Kinixys belJin.nn. zulllon sis subs)1 . n. 47 1 Kinixys n. ustra lis 8p. It. 477 Kinixys da.rlingi Blgr. 4, 1 Kini xys jordn.ni sp . n . 482 Kinixys yonn gi ap. n. 4SG Kini xys lo bn.ts ia na Pou'er 488 H omopus WaMb. ..HHi Pseudomopus g. n . ·Hlli T estlld o L . 4!)H Neotestlldo g. n. 50" 462 JOHN HEWI'IT. THE material dealt wi th in this revi ew has bef' 1l derived from varioll s sources. A good portion of it is contained in the Albany Musemu, and for the loan of specimens I am especia.lly indebted to the Mu seums at Pretoria, Kimberley and Pietermaritzburg. It, may be .aid that the. present study again illustrates the fact t.hat the closer a group of organisms is studied and the wider the area from which they are obt.ained, the greater is the difficnlty ill formulating any clear diagnosis of specific characters. -

Russian Tortoise Care Scientific Taxonomy/Name: Testudo Horsfieldi

[email protected] http://www.aeacarizona.com Address: 7 E. Palo Verde St., Phone: (480) 706-8478 Suite #1 Fax: (480) 393-3915 Gilbert, AZ 85296 Emergencies: Page (602) 351-1850 Russian Tortoise Care Scientific Taxonomy/name: Testudo horsfieldi Avg. carapace length: Males average around 5.5 inches and 1.3 pounds. Females average around 7.5 inches and 3 pounds. Natural location: Dry/arid, hot areas around the Mediterranean Sea (i.e. parts of Turkey, Afghanistan, Russia, Iran, China, and Pakistan). Russian tortoises live in burrows for nine months of the year. They are the only land tortoise (Testudo spp.) without a hinge on their plastron near the rear legs, and the only land tortoise with only four claws/toes on each foot. Temperature: 70-80 degrees Fahrenheit with basking area of 90 degrees. For tortoises kept inside, keep thermometers at various locations in the enclosure in order to check the temperature in their environment. Humidity: 30-50% (dry environment). Use a hydrometer to check humidity levels in the enclosure. Lighting: Natural sunlight (not blocked by windows) is the best source of light for tortoises (and other reptiles)! If being kept indoors during the winter or due to an illness, use a broad- spectrum heat bulb. The most efficient light source is the Exo Terra Solar Glo. It is a mercury vapor bulb that emits heat, UVB, and UVA. UV light has multiple benefits, including calcium metabolism and improved appetite and activity. Proper calcium metabolism helps protect against metabolic bone disease. Follow manufacture directions on proper installation and use a clamp lamp with a ceramic fixture to prevent melting. -

Growing and Shrinking in the Smallest Tortoise, Homopus Signatus Signatus: the Importance of Rain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Oecologia (2007) 153:479–488 DOI 10.1007/s00442-007-0738-7 GLOBAL CHANGE AND CONSERVATION ECOLOGY Growing and shrinking in the smallest tortoise, Homopus signatus signatus: the importance of rain Victor J. T. Loehr · Margaretha D. Hofmeyr · Brian T. Henen Received: 21 November 2006 / Accepted: 21 March 2007 / Published online: 24 April 2007 © Springer-Verlag 2007 Abstract Climate change models predict that the range of dorso-ventrally, so a reduction in internal matter due to the world’s smallest tortoise, Homopus signatus signatus, starvation or dehydration may have caused SH to shrink. will aridify and contract in the next decades. To evaluate Because the length and width of the shell seem more rigid, the eVects of annual variation in rainfall on the growth of reversible bone resorption may have contributed to shrink- H. s. signatus, we recorded annual growth rates of wild age, particularly of the shell width and plastron length. individuals from spring 2000 to spring 2004. Juveniles Based on growth rates for all years, female H. s. signatus grew faster than did adults, and females grew faster than need 11–12 years to mature, approximately twice as long as did males. Growth correlated strongly with the amount of would be expected allometrically for such a small species. rain that fell during the time just before and within the However, if aridiWcation lowers average growth rates to the growth periods. Growth rates were lowest in 2002–2003, level of 2002–2003, females would require 30 years to when almost no rain fell between September 2002 and mature. -

Conservation of South African Tortoises with Emphasis on Their Apicomplexan Haematozoans, As Well As Biological and Metal-Fingerprinting of Captive Individuals

CONSERVATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN TORTOISES WITH EMPHASIS ON THEIR APICOMPLEXAN HAEMATOZOANS, AS WELL AS BIOLOGICAL AND METAL-FINGERPRINTING OF CAPTIVE INDIVIDUALS By Courtney Antonia Cook THESIS submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (Ph.D.) in ZOOLOGY in the FACULTY OF SCIENCE at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Supervisor: Prof. N. J. Smit Co-supervisors: Prof. A. J. Davies and Prof. V. Wepener June 2012 “We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals. Remote from universal nature, and living by complicated artifice, man in civilization surveys the creature through the glass of his knowledge and sees thereby a feather magnified and the whole image in distortion. We patronize them for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate of having taken form so far below ourselves. And therein we err, and greatly err. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.” Henry Beston (1928) ABSTRACT South Africa has the highest biodiversity of tortoises in the world with possibly an equivalent diversity of apicomplexan haematozoans, which to date have not been adequately researched. Prior to this study, five apicomplexans had been recorded infecting southern African tortoises, including two haemogregarines, Haemogregarina fitzsimonsi and Haemogregarina parvula, and three haemoproteids, Haemoproteus testudinalis, Haemoproteus balazuci and Haemoproteus sp.