Early Steps of Mammary Stem Cell Transformation by Exogenous Signals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is an Activator of the Human Estrogen Receptor Alpha

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Newcastle University E-Prints 1 The ionic liquid 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium (M8OI) is an activator of the human estrogen receptor alpha Alistair C. Leitch1, Anne F. Lakey1, William E. Hotham1, Loranne Agius1, George E.N. Kass2, Peter G. Blain1, Matthew C. Wright1,* 1Institute Cellular Medicine, Health Protection Research Unit, Level 4 Leech, Newcastle University, Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom NE24HH. 2European Food Safety Authority, Via Carlo Magno 1A, 43126 Parma, Italy. *Corresponding author. Address: Institute Cellular Medicine, Level 4 Leech Building; Newcastle University, Framlington Place, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK. [email protected] Email addresses: [email protected] (A. Leitch), [email protected] (A. Lakey), [email protected] (W. Hotham), [email protected] (L Aguis), , [email protected] (G Kass), [email protected] (P. Blain) [email protected] (M. Wright). Abbreviations AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; ICI182780, also known as fulvestrant; E2, 17β estradiol; EE, ethinylestradiol; ERα, estrogen receptor alpha, also known as NR3A1; ERβ, estrogen receptor beta, also known as ER3A2; M8OI, 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride, also known as C8min; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; PPARα, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha; TFF1, trefoil factor 1. 2 ABSTRACT Recent environmental sampling around a landfill site in the UK demonstrated that unidentified xenoestrogens were present at higher levels than control sites; that these xenoestrogens were capable of super-activating (resisting ligand-dependent antagonism) the murine variant 2 ERβ and that the ionic liquid 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride (M8OI) was present in some samples. -

Memorandum Date: June 6, 2014

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Food and Drug Administration Memorandum Date: June 6, 2014 From: Bisphenol A (BPA) Joint Emerging Science Working Group Smita Baid Abraham, M.D. ∂, M. M. Cecilia Aguila, D.V.M. ⌂, Steven Anderson, Ph.D., M.P.P.€* , Jason Aungst, Ph.D.£*, John Bowyer, Ph.D. ∞, Ronald P Brown, M.S., D.A.B.T.¥, Karim A. Calis, Pharm.D., M.P.H. ∂, Luísa Camacho, Ph.D. ∞, Jamie Carpenter, Ph.D.¥, William H. Chong, M.D. ∂, Chrissy J Cochran, Ph.D.¥, Barry Delclos, Ph.D.∞, Daniel Doerge, Ph.D.∞, Dongyi (Tony) Du, M.D., Ph.D. ¥, Sherry Ferguson, Ph.D.∞, Jeffrey Fisher, Ph.D.∞, Suzanne Fitzpatrick, Ph.D. D.A.B.T. £, Qian Graves, Ph.D.£, Yan Gu, Ph.D.£, Ji Guo, Ph.D.¥, Deborah Hansen, Ph.D. ∞, Laura Hungerford, D.V.M., Ph.D.⌂, Nathan S Ivey, Ph.D. ¥, Abigail C Jacobs, Ph.D.∂, Elizabeth Katz, Ph.D. ¥, Hyon Kwon, Pharm.D. ∂, Ifthekar Mahmood, Ph.D. ∂, Leslie McKinney, Ph.D.∂, Robert Mitkus, Ph.D., D.A.B.T.€, Gregory Noonan, Ph.D. £, Allison O’Neill, M.A. ¥, Penelope Rice, Ph.D., D.A.B.T. £, Mary Shackelford, Ph.D. £, Evi Struble, Ph.D.€, Yelizaveta Torosyan, Ph.D. ¥, Beverly Wolpert, Ph.D.£, Hong Yang, Ph.D.€, Lisa B Yanoff, M.D.∂ *Co-Chair, € Center for Biologics Evaluation & Research, £ Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, ∂ Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, ¥ Center for Devices and Radiological Health, ∞ National Center for Toxicological Research, ⌂ Center for Veterinary Medicine Subject: 2014 Updated Review of Literature and Data on Bisphenol A (CAS RN 80-05-7) To: FDA Chemical and Environmental Science Council (CESC) Office of the Commissioner Attn: Stephen M. -

3 Cleavage Products of Notch 2/Site and Myelopoiesis by Dysregulating

ADAM10 Overexpression Shifts Lympho- and Myelopoiesis by Dysregulating Site 2/Site 3 Cleavage Products of Notch This information is current as David R. Gibb, Sheinei J. Saleem, Dae-Joong Kang, Mark of October 4, 2021. A. Subler and Daniel H. Conrad J Immunol 2011; 186:4244-4252; Prepublished online 2 March 2011; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003318 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/186/7/4244 Downloaded from Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2011/03/02/jimmunol.100331 Material 8.DC1 http://www.jimmunol.org/ References This article cites 45 articles, 16 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/186/7/4244.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists by guest on October 4, 2021 • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2011 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology ADAM10 Overexpression Shifts Lympho- and Myelopoiesis by Dysregulating Site 2/Site 3 Cleavage Products of Notch David R. -

ADAM10 Site-Dependent Biology: Keeping Control of a Pervasive Protease

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review ADAM10 Site-Dependent Biology: Keeping Control of a Pervasive Protease Francesca Tosetti 1,* , Massimo Alessio 2, Alessandro Poggi 1,† and Maria Raffaella Zocchi 3,† 1 Molecular Oncology and Angiogenesis Unit, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico S. Martino Largo R. Benzi 10, 16132 Genoa, Italy; [email protected] 2 Proteome Biochemistry, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, 20132 Milan, Italy; [email protected] 3 Division of Immunology, Transplants and Infectious Diseases, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, 20132 Milan, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work as last author. Abstract: Enzymes, once considered static molecular machines acting in defined spatial patterns and sites of action, move to different intra- and extracellular locations, changing their function. This topological regulation revealed a close cross-talk between proteases and signaling events involving post-translational modifications, membrane tyrosine kinase receptors and G-protein coupled recep- tors, motor proteins shuttling cargos in intracellular vesicles, and small-molecule messengers. Here, we highlight recent advances in our knowledge of regulation and function of A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase (ADAM) endopeptidases at specific subcellular sites, or in multimolecular com- plexes, with a special focus on ADAM10, and tumor necrosis factor-α convertase (TACE/ADAM17), since these two enzymes belong to the same family, share selected substrates and bioactivity. We will discuss some examples of ADAM10 activity modulated by changing partners and subcellular compartmentalization, with the underlying hypothesis that restraining protease activity by spatial Citation: Tosetti, F.; Alessio, M.; segregation is a complex and powerful regulatory tool. -

Cell-Autonomous FLT3L Shedding Via ADAM10 Mediates Conventional Dendritic Cell Development in Mouse Spleen

Cell-autonomous FLT3L shedding via ADAM10 mediates conventional dendritic cell development in mouse spleen Kohei Fujitaa,b,1, Svetoslav Chakarovc,1, Tetsuro Kobayashid, Keiko Sakamotod, Benjamin Voisind, Kaibo Duanc, Taneaki Nakagawaa, Keisuke Horiuchie, Masayuki Amagaib, Florent Ginhouxc, and Keisuke Nagaod,2 aDepartment of Dentistry and Oral Surgery, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo 160-8582, Japan; bDepartment of Dermatology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo 160-8582, Japan; cSingapore Immunology Network, Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Biopolis, 138648 Singapore; dDermatology Branch, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; and eDepartment of Orthopedic Surgery, National Defense Medical College, Tokorozawa 359-8513, Japan Edited by Kenneth M. Murphy, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, and approved June 10, 2019 (received for review November 4, 2018) Conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) derive from bone marrow (BM) intocDC1sorcDC2stakesplaceintheBM(3),andthese precursors that undergo cascades of developmental programs to pre-cDC1s and pre-cDC2s ultimately differentiate into cDC1s terminally differentiate in peripheral tissues. Pre-cDC1s and pre- and cDC2s after migrating to nonlymphoid and lymphoid tissues. + + cDC2s commit in the BM to each differentiate into CD8α /CD103 cDCs are short-lived, and their homeostatic maintenance relies + cDC1s and CD11b cDC2s, respectively. Although both cDCs rely on on constant replenishment from the BM precursors (5). The cy- the cytokine FLT3L during development, mechanisms that ensure tokine Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (FLT3L) (12), by cDC accessibility to FLT3L have yet to be elucidated. Here, we gen- signaling through its receptor FLT3 expressed on DC precursors, erated mice that lacked a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) is essential during the development of DCs (7, 13). -

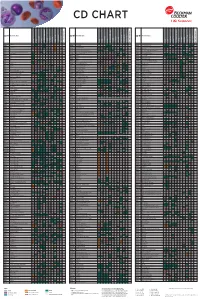

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

The Role of the TGF- Co-Receptor Endoglin in Cancer

1 The role of the TGF- co-receptor endoglin in cancer Eduardo Pérez-Gómez1,†, Gaelle del Castillo1, Juan Francisco Santibáñez2, Jose Miguel López-Novoa3, Carmelo Bernabéu4 and 1,* Miguel Quintanilla . 1Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas Alberto Sols, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC)-Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, 28029-Madrid, Spain; 2Institute for Medical Research, University of Belgrado, Belgrado, Serbia; 3Instituto Reina Sofía de Investigación Nefrológica, Departamento de Fisiología y Farmacología, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain; 4Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, CSIC, and CIBER de Enfermedades Raras (CIBERER), Madrid, Spain. E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] † Current address: Departamento de Bioquímica y Biología Molecular I, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain *Corresponding author 2 ABSTRACT Endoglin (CD105) is an auxiliary membrane receptor of transforming growth factor- (TGF-) that interacts with type I and type II TGF- receptors and modulates TGF- signalling. Mutations in endoglin are involved in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia type I, a disorder characterized by cutaneous telangiectasias, epistaxis (nosebleeds) and major arteriovenous shunts, mainly in liver and lung. Endoglin is overexpressed in the tumor-associated vascular endothelium where it modulates angiogenesis. This feature makes endoglin a promising target for antiangiogenic cancer therapy. Recent studies on human and experimental models of carcinogenesis point to an important tumor cell-autonomous role of endoglin by regulating proliferation, migration, invasion and metastasis. These studies suggest that endoglin behaves as a suppressor of malignancy in experimental and human carcinogenesis. In this review, we evaluate the implication of endoglin in tumor development underlying studies developed in our laboratories in recent years. -

Shrna Kinome Screen Identifies TBK1 As a Therapeutic Target for HER2 Breast Cancer

Published OnlineFirst January 31, 2014; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2138 Cancer Tumor and Stem Cell Biology Research shRNA Kinome Screen Identifies TBK1 as a Therapeutic Target for HER2þ Breast Cancer Tao Deng1, Jeff C. Liu1, Philip E.D. Chung1, David Uehling2, Ahmed Aman2, Babu Joseph2, Troy Ketela3, Zhe Jiang1, Nathan F. Schachter4, Robert Rottapel5, Sean E. Egan4, Rima Al-awar2,6, Jason Moffat3, and Eldad Zacksenhaus1 Abstract þ HER2 breast cancer is currently treated with chemotherapy plus anti-HER2 inhibitors. Many patients do not respond or relapse with aggressive metastatic disease. Therefore, there is an urgent need for new therapeutics that þ can target HER2 breast cancer and potentiate the effect of anti-HER2 inhibitors, in particular those that can target tumor-initiating cells (TIC). Here, we show that MMTV-Her2/Neu mammary tumor cells cultured as nonadherent spheres or as adherent monolayer cells select for stabilizing mutations in p53 that "immortalize" the cultures and that, after serial passages, sphere conditions maintain TICs, whereas monolayer cells gradually lose these tumorigenic cells. Using tumorsphere formation as surrogate for TICs, we screened p53-mutant þ Her2/Neu tumorsphere versus monolayer cells with a lentivirus short hairpin RNA kinome library. We identified kinases such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase and the TGFbR protein family, previously implicated þ in HER2 breast cancer, as well as autophagy factor ATG1/ULK1 and the noncanonical IkB kinase (IKK), þ TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), which have not been previously linked to HER2 breast cancer. Knockdown of TBK1 or pharmacologic inhibition of TBK1 and the related protein, IKKe, suppressed growth of both mouse þ and human HER2 breast cancer cells. -

HCC and Cancer Mutated Genes Summarized in the Literature Gene Symbol Gene Name References*

HCC and cancer mutated genes summarized in the literature Gene symbol Gene name References* A2M Alpha-2-macroglobulin (4) ABL1 c-abl oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase (4,5,22) ACBD7 Acyl-Coenzyme A binding domain containing 7 (23) ACTL6A Actin-like 6A (4,5) ACTL6B Actin-like 6B (4) ACVR1B Activin A receptor, type IB (21,22) ACVR2A Activin A receptor, type IIA (4,21) ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 (5) ADAMTS9 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 9 (4) ADCY2 Adenylate cyclase 2 (brain) (26) AJUBA Ajuba LIM protein (21) AKAP9 A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein (yotiao) 9 (4) Akt AKT serine/threonine kinase (28) AKT1 v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 (5,21,22) AKT2 v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 2 (4) ALB Albumin (4) ALK Anaplastic lymphoma receptor tyrosine kinase (22) AMPH Amphiphysin (24) ANK3 Ankyrin 3, node of Ranvier (ankyrin G) (4) ANKRD12 Ankyrin repeat domain 12 (4) ANO1 Anoctamin 1, calcium activated chloride channel (4) APC Adenomatous polyposis coli (4,5,21,22,25,28) APOB Apolipoprotein B [including Ag(x) antigen] (4) AR Androgen receptor (5,21-23) ARAP1 ArfGAP with RhoGAP domain, ankyrin repeat and PH domain 1 (4) ARHGAP35 Rho GTPase activating protein 35 (21) ARID1A AT rich interactive domain 1A (SWI-like) (4,5,21,22,24,25,27,28) ARID1B AT rich interactive domain 1B (SWI1-like) (4,5,22) ARID2 AT rich interactive domain 2 (ARID, RFX-like) (4,5,22,24,25,27,28) ARID4A AT rich interactive domain 4A (RBP1-like) (28) ARID5B AT rich interactive domain 5B (MRF1-like) (21) ASPM Asp (abnormal -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Adverse Effects of Digoxin, As Xenoestrogen, on Some Hormonal and Biochemical Patterns of Male Albino Rats Eman G.E.Helal *, Mohamed M.M

The Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine (October 2013) Vol. 53, Page 837– 845 Adverse Effects of Digoxin, as Xenoestrogen, on Some Hormonal and Biochemical Patterns of Male Albino Rats Eman G.E.Helal *, Mohamed M.M. Badawi **,Maha G. Soliman*, Hany Nady Yousef *** , Nadia A. Abdel-Kawi*, Nashwa M. G. Abozaid** Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University (Girls)*, Department of Biochemistry, National organization for Drug Control and Research** Department of Biological and Geological Sciences, Faculty of Education, Ain Shams University*** Abstract Background: Xenoestrogens are widely used environmental chemicals that have recently been under scrutiny because of their possible role as endocrine disrupters. Among them is digoxin that is commonly used in the treatment of heart failure and atrial dysrhythmias. Digoxin is a cardiac glycoside derived from the foxglove plant, Digitalis lanata and suspected to act as estrogen in living organisms. Aim of the work: The purpose of the current study was to elucidate the sexual hormonal and biochemical patterns of male albino rats under the effect of digoxin treatment. Material and Methods: Forty six male albino rats (100-120g) were divided into three groups (16 rats for each). Half of the groups were treated daily for 15 days and the other half for 30 days. Control group: Animals without any treatment. Digoxin L group: orally received digoxin at low dose equivalent of 0.0045mg/200g.b.wt. Digoxin H group: administered digoxin orally at high dose equivalent of 0.0135mg/200g.b.wt. At the end of the experimental periods, blood was collected and serum was separated for estimation the levels of prolactin (PRL), FSH, LH, total testosterone (total T), aspartate amino transferase (AST), alanine amino transferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), urea, creatinine, total proteins, albumin, total lipids, total cholesterol (total-chol), Triglycerides (TG), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-chol) and high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-chol). -

Two Novel Disease-Causing Variants in BMPR1B Are Associated with Brachydactyly Type A1

European Journal of Human Genetics (2015) 23, 1640–1645 & 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1018-4813/15 www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Two novel disease-causing variants in BMPR1B are associated with brachydactyly type A1 Lemuel Racacho1,2, Ashley M Byrnes1,3, Heather MacDonald3, Helen J Dranse4, Sarah M Nikkel5,6, Judith Allanson6, Elisabeth Rosser7, T Michael Underhill4 and Dennis E Bulman*,1,2,5 Brachydactyly type A1 is an autosomal dominant disorder primarily characterized by hypoplasia/aplasia of the middle phalanges of digits 2–5. Human and mouse genetic perturbations in the BMP-SMAD signaling pathway have been associated with many brachymesophalangies, including BDA1, as causative mutations in IHH and GDF5 have been previously identified. GDF5 interacts directly as the preferred ligand for the BMP type-1 receptor BMPR1B and is important for both chondrogenesis and digit formation. We report pathogenic variants in BMPR1B that are associated with complex BDA1. A c.975A4C (p. (Lys325Asn)) was identified in the first patient displaying absent middle phalanges and shortened distal phalanges of the toes in addition to the significant shortening of middle phalanges in digits 2, 3 and 5 of the hands. The second patient displayed a combination of brachydactyly and arachnodactyly. The sequencing of BMPR1B in this individual revealed a novel c.447-1G4A at a canonical acceptor splice site of exon 8, which is predicted to create a novel acceptor site, thus leading to a translational reading frameshift. Both mutations are most likely to act in a dominant-negative manner, similar to the effects observed in BMPR1B mutations that cause BDA2.