Absentee Landlords and Land Utilization in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report of the Colonies. Uganda 1920

This document was created by the Digital Content Creation Unit University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2010 COLONIAL REPORTS—ANNUAL. No. 1112. UGANDA. REPORT FOR 1920 (APRIL TO DECEMBER). (For Report for 1919-1920 see No. 1079.) LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased through any T3ookscller or directly from H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses: IMPERIAL HOUSE, KINGSWAY, LONC-ON, W.C.2, and 28, ABINGDON STREET, LONDON, S.W.I; 37, PETER STREET, MANCHESTER; 1, ST. ANDREW'S CRESCENT, CARDIFF; 23, FORTH STREET, EDINBURGH; or from EASON & SON. LTD., 40-41, LOWER SACKVII.I-E STREET, DUBLIN. 1922. Price 9d. Net. INDEX. PREFACE I. GENERAL OBSERVATIONS II. GOVERNMENT FINANCE III. TRADE, AGRICULTURE AND INDUSTRIES IV. LEGISLATION V. EDUCATION VI. CLIMATE AND METEOROLOGY VII. COMMUNICATIONS.. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS' RECEIVED &0dUM£NT$ DIVISION -fTf-ViM-(Hff,>itmrtn«l,.ni ii ii in. No. 1112. Annual Report ON THE Uganda Protectorate FOR THE PERIOD 1st April to 31st December 1920.* PREFACE. 1. Geographical Description.—The territories comprising the Uganda Protectorate lie between Belgian Congo, the Anglo- Egyptian Sudan, Kenya, and the country known until recently as German East Africa (now Tanganyika Territory). The Protectorate extends from one degree of south latitude to the northern limits of the navigable waters of the Victoria Nile at Nimule. It is flanked on the east by the natural boundaries of Lake Rudolf, the river Turkwel, Mount Elgon (14,200 ft.), and the Sio river, running into the north-eastern waters of Lake Victoria, whilst the outstanding features on the western side are the Nile Watershed, Lake Albert, the river Semliki, the Ruwenzori Range (16,794 ft.), and Lake Edward. -

Journal of Eastern African Studies Rethinking the State in Idi Amin's Uganda: the Politics of Exhortation

This article was downloaded by: [Cambridge University Library] On: 20 July 2015, At: 20:55 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Journal of Eastern African Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjea20 Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation Derek R. Peterson a & Edgar C. Taylor a a Department of History , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , MI , 48109 , USA Published online: 26 Feb 2013. To cite this article: Derek R. Peterson & Edgar C. Taylor (2013) Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 7:1, 58-82, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

———— “Mudo”: the Soga 'Little Red Riding Hood'

LILLIAN BUKAAYI TIBASIIMA ———— º “Mudo”: The Soga ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ ABSTRACT This essay analyses the social underpinnings of the oral tale of “Mudo,” which belongs to the Aarne–Thompson tale type 333, along with a group of similar tales that resemble the action and movement of “Little Red Riding Hood.” Basic to the exposition is Adolf Bastian’s assertion of the fundamental similarity of ideas between all social groups. In the “Mudo” story and its Ugandan variants, the victim is a solitary little girl and the villain a male ogre who devises ways of eating her; the ogre is mostly successful, although in some variants the girl manages to escape. Although these tales come from a great range of cultures and different geographical locations, and the counterpart of the ogre in the European tales is a wolf in disguise, they share elements of plot, characteriza- tion, and motif, and address similar concerns. Introduction USOGA IS PART OF EAS TERN UGANDA, surrounded by water. The B Rev. Fredrick Kisuule Kaliisa1 notes: To the west is river Kiira (Nile) marking the boundary between Buganda and Busoga. To the East is river Mpologoma separating Busoga from Bukedi. To the North are river Mpologoma and Lake Kyoga, forming the boundary be- tween Busoga and Lango. To the south, is Lake Victoria (Nalubaale). It might be the result of the geographical location of Busoga that ogre stories were composed to warn the people against impending harm if they went out alone and stayed in secluded places. Nnalongo Lukude emphasizes this: Historically, Busoga was surrounded by bodies of water and forests, it was very bushy and as a result harboured many wild animals, some of which were man-eaters. -

Table of Contents List of Tables

TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 PROJECT IMPACTS ................................................................................................................ 138 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 138 Summary of Impacts ................................................................................................................. 138 Impacts on Land ....................................................................................................................... 143 6.3.1 Land Requirements and Land Use Context ......................................................................... 143 Impacts on houses – Physical Displacement ........................................................................... 149 Impacts on other structures ...................................................................................................... 153 Impacts on Communal Buildings .............................................................................................. 159 Graves and Cultural Heritage Assets ....................................................................................... 160 Impacts on Crops and Economic Trees .................................................................................... 160 Impacts on Livelihood Activities – Economic Displacement ..................................................... 166 Impacts on Public Utilities/Infrastructure .................................................................................. -

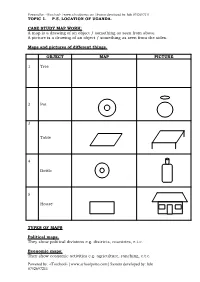

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Detailed Curriculum Vitae Prof. Moses Muhumuza

Curriculum Vitae Assoc. Prof. Moses Muhumuza (PhD)* Bachelor of Science with Education (Biology & Chemistry), Master of Science (Biology)- Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Uganda, and Doctor of Philosophy (Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences)- University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa *For correspondence: Email: [email protected], Tel: +256772565565/+256756723711 August 2020 Page 1 of 39 Curriculum vitae- Assoc. Prof. Dr. Moses Muhumuza [Bsc. Ed. (Bio.&Chem.)-MUST, Msc. (Bio.)-MUST, PhD (APES)-WITS] SUMMARY OF THE ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL PROFILE Assoc. Prof. Dr. Moses Muhumuza was trained as a graduate teacher by profession specializing in Biology and Chemistry teaching subjects. He eventually advanced his career to focus on Biological Sciences. He has a Masters of Science Degree in Biology specializing in Natural Resource Management, and a PhD in Animal, Plant, and Environmental Sciences focusing on social aspects of rural communities neighboring protected areas in an African context. He also has certificates in project planning and management, project monitoring and evaluation, data analysis and various short course trainings. His expertise stretches across a wider spectrum in both the natural and social sciences. By virtue of teaching at secondary school and university levels, he has engaged in a variety of teaching and research methodologies and accumulated experience in developing self-study materials, writing competitive research proposals and informative research reports. He currently lectures introductory and advanced courses in Biological Sciences, Social science for Conservation, Science education, Climate Change, and Research Methods at Mountains of the Moon University. He has supervised to completion over 30 students’ research projects in sciences and liberal arts both at undergraduate and postgraduate level. -

Political Question Doctrine in Uganda

Political Question Doctrine in Uganda An analysis of the technicalities on the realization of the freedoms of expression, association and Assembly in Uganda J. Oloka-Onyango MAKERERE UNIVERSITY Acknowledgment This paper was written for Chapter Four Uganda by J. Oloka-Onyango, a Professor of Law at Makerere University, School of Law. Research assistance was provided by Dorah Kankunda, Dan Bill Opio, and Joseph Byomuhangyi. Copyright © 2017 Chapter Four Uganda All rights reserved. Chapter Four Uganda is an independent not-for-profit organisation dedicated to the protection of civil liberties and promotion of human rights for all. We promote human dignity and advance rights through robust, strategic and non-discriminatory legal response. For more information, please visit: http://chapterfouruganda.com The Production of this paper was generously funded by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). 01 05 Introduction Association and its 4 Protection and Violation 24 02 06 Technicalities and the The Question of Assembly PQD: The Good, the 30 Bad and the Ugly 6 Table of Contents 03 07 The Constitutional Conclusion Framework and the 34 Movement towards Inclusion 10 04 Freedom of Expression, Media Rights and Access to Information (A2I) 4.1 Expression and Media 15 Rights 4.2 Access to Information 19 01 Introduction 4 Political Question Doctrine in Uganda nsofar as a great deal of the Law is concerned with access to and the delivery of Justice, it is something of a surprise how much of the Law is in fact devoted to its subversion. Nowhere is the subversion of Justice more apparent than in the use of technicalities by lawyers in order to prevent a matter from being fully heard by the Icourts of law. -

Tooro Kingdom 2 2

ClT / CIH /ITH 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 0090400007 I Le I 09 MAl 2012 NOMINATION OF EMPAAKO TRADITION FOR W~~.~.Q~~}~~~~.P?JIPNON THE LIST OF INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE IN NEED OF URGENT SAFEGUARDING 2012 DOCUMENTS OF REQUEST FROM STAKEHOLDERS Documents Pages 1. Letter of request form Tooro Kingdom 2 2. Letter of request from Bunyoro Kitara Kingdom 3 3. Statement of request from Banyabindi Community 4 4. Statement of request from Batagwenda Community 9 5. Minute extracts /resolutions from local government councils a) Kyenjojo District counciL 18 b) Kabarole District Council 19 c) Kyegegwa District Council 20 d) Ntoroko District Council 21 e) Kamwenge District Council 22 6. Statement of request from Area Member of Ugandan Parliament 23 7. Letters of request from institutions, NOO's, Associations & Companies a) Kabarole Research & Resource Centre 24 b) Mountains of the Moon University 25 c) Human Rights & Democracy Link 28 d) Rural Association Development Network 29 e) Modrug Uganda Association Ltd 34 f) Runyoro - Rutooro Foundation 38 g) Joint Effort to Save the Environment (JESE) .40 h) Foundation for Rural Development (FORUD) .41 i) Centre of African Christian Studies (CACISA) 42 j) Voice of Tooro FM 101 43 k) Better FM 44 1) Tooro Elders Forum (Isaazi) 46 m) Kibasi Elders Association 48 n) DAJ Communication Ltd 50 0) Elder Adonia Bafaaki Apuuli (Aged 94) 51 8. Statements of Area Senior Cultural Artists a) Kiganlbo Araali 52 b) Master Kalezi Atwoki 53 9. Request Statement from Students & Youth Associations a) St. Leo's College Kyegobe Student Cultural Association 54 b) Fort Portal Institute of Commerce Student's Cultural Association 57 c) Fort Portal School of Clinical Officers Banyoro, Batooro Union 59 10. -

Characterisation of the Livestock Production System and Potential for Enhancing Productivity Through Improved Feeding in Kiboga

Characterisation of the livestock production system and potential for enhancing productivity through improved feeding in Kiboga West DFBA, Kyankwanzi district, Uganda By: Jane Kugonza, Ronald Wabwire, Pius Lutakome, Ben Lukuyu and Josephine Kirui East African Dairy Development Project (EADD) The Feed Assessment Tool (FEAST) is a systematic method to assess local feed resource availability and use. It helps in the design of intervention strategies aiming to optimize feed utilization and animal production. More information and the manual can be obtained at www.ilri.org/feast FEAST is a tool in constant development and improvement. Feedback is welcome and should be directed [email protected]. The International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) is not responsible for the quality and validity of results obtained using the FEAST methodology. The Feed Assessment Tool (FEAST) was used to characterize the livestock production system and in particular feed‐related aspects in Kiboga West dairy farmers association (DFBA) of Kyankwanzi, Kyankwanzi district, Uganda. The assessment was carried out through structured group discussions and completion of short questionnaires by key farmers’ representatives1. The following are the findings of the assessment and conclusions for further action. Farming system Kyankwanzi was formerly in Kiboga district but obtained district status in 2004 and is located in the extreme part of Buganda region. The travel distance by road is approximately 220 kilometres from the capital city of Uganda, Kampala. Households in this area are composed of approximately 14 (range 6-20) members and utilise on average 15 acres of pastoral land. Table 1 shows farmers perceptions about average land sizes for different categories of farmers. -

A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884

Peripheral Identities in an African State: A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884 Aidan Stonehouse Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Ph.D The University of Leeds School of History September 2012 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor Shane Doyle whose guidance and support have been integral to the completion of this project. I am extremely grateful for his invaluable insight and the hours spent reading and discussing the thesis. I am also indebted to Will Gould and many other members of the School of History who have ably assisted me throughout my time at the University of Leeds. Finally, I wish to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council for the funding which enabled this research. I have also benefitted from the knowledge and assistance of a number of scholars. At Leeds, Nick Grant, and particularly Vincent Hiribarren whose enthusiasm and abilities with a map have enriched the text. In the wider Africanist community Christopher Prior, Rhiannon Stephens, and especially Kristopher Cote and Jon Earle have supported and encouraged me throughout the project. Kris and Jon, as well as Kisaka Robinson, Sebastian Albus, and Jens Diedrich also made Kampala an exciting and enjoyable place to be. -

Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda, In: Africa Spectrum, 49, 3, 29-54

Africa Spectrum Quinn, Joanna R. (2014), Tradition?! Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda, in: Africa Spectrum, 49, 3, 29-54. URN: http://nbn-resolving.org/urn/resolver.pl?urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-7811 ISSN: 1868-6869 (online), ISSN: 0002-0397 (print) The online version of this and the other articles can be found at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of African Affairs in co-operation with the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Uppsala and Hamburg University Press. Africa Spectrum is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To subscribe to the print edition: <[email protected]> For an e-mail alert please register at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Africa Spectrum is part of the GIGA Journal Family which includes: Africa Spectrum ●● Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs ●● Journal of Politics in Latin America <www.giga-journal-family.org> Africa Spectrum 3/2014: 29-54 Tradition?! Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda Joanna R. Quinn Abstract: This contribution traces the importance of traditional institu- tions in rehabilitating societies in general terms and more particularly in post-independence Uganda. The current regime, partly by inventing “traditional” cultural institutions, partly by co-opting them for its own interests, contributed to a loss of legitimacy of those who claim respon- sibility for customary law. More recently, international prosecutions have complicated the use of customary mechanisms within such societies.