Ing the New Woman in Contemporary Ugandan Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterization of the Soil Nematode Fauna of Makerere Hill, Kampala, Uganda

Vol. 11(6), pp. 70-84, Oct-Dec 2019 DOI: 10.5897/JEN2019.0239 Article Number: F82FA2462098 ISSN 2006-9855 Copyright ©2019 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Journal of Entomology and Nematology http://www.academicjournals.org/JEN Full Length Research Paper Characterization of the Soil Nematode Fauna of Makerere Hill, Kampala, Uganda Nzeako S. O.1*, Talwana H.2, Teye E.3, Sekanjako I.2, Nabweteme J.2 and Businge M. A.3 1Department of Animal and Environmental Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. 2Department of Agriculture Engineering, University of Cape Coast, College of Agriculture and Natural Science, School Agriculture, Cape Coast, Ghana. 3School of Agricultural Sciences, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Makerere University, Makerere, Kampala, Uganda. Received 17 June, 2019; Accepted 13 August, 2019 Soil nematode faunal analysis is necessary to ascertain the health status of the soil ecosystem. Composite soil samples were taken at designated sites; A, B, C and D from the Makerere Hill area, Kampala and analyzed to characterize the nematode fauna status. Soil samples were collected vertically at 0-5 cm, 5-10 cm and 10-15 cm core depths with a 5 cm wide soil auger. A total of 7,900 nematodes were collected from the study out of which 1,720 (21.8%) nematodes came from 0-5 cm core depth, 5,270 (66.7) from 5-10 cm core depth and 910 (11.52) from the 10-15 cm core depth. Species diversity showed nine orders of nematodes comprising twenty four families and forty nine species. -

Muzibu-Azaala-Mpanga Tombs of Buganda Kings at Kasubi

Mission report on the preparation of the reconstruction of Muzibu-Azaala-Mpanga Tombs of Buganda Kings at Kasubi A World Heritage property of Uganda April 2010 Mission undertaken from 22nd to 26th August 2011 by: Lazare Eloundou, architect, UNESCO Sébastien Moriset, architect, CRAterre-ENSAG In close collaboration with the Government of Uganda and the Buganda Kingdom August 2011 2 Mission report on the preparation of the reconstruction of Muzibu‐Azaala‐Mpanga Tombs of Buganda Kings at Kasubi A World Heritage property of Uganda (C 1022) This document is the result of the mission undertaken in Kampala from 22nd to 26th August 2011, which involved the following experts : Mr Lazare Eloundou, architect, Chief of the Africa Unit, UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Paris, France Mr Sebastien Moriset, architect, CRAterre, National Superior School of Architecture of Grenoble, France This report was prepared by Sébastien Moriset with inputs by Lazare Eloundou For more information on the reconstruction project, contact: Lazare Eloundou Chief of Africa Unit UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE 7 Place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP FRANCE Tel: +33 1 45 68 19 38 email : l.eloundou‐[email protected] Sébastien Moriset CRAterre‐ENSAG International centre for earth construction, National Superior School of Architecture of Grenoble BP 2636 38036 GRENOBLE Cedex 2 FRANCE Telephone + 33 4 76 69 83 35 Cell: +33 6 46 52 74 35 email: [email protected] Rose Nkaale Mwanja, Ag. Commissioner Uganda Museums Department of Museums and monuments, Ministry of Tourism, Wildlife and Heritage P.O. Box 5718, Kampala, Uganda Telephone +256 41 232 707 Cell: +256 77 248 56 24 email : [email protected] Jonathan Nsubuga Architect, j.e.nsubuga & Associates P.O. -

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS of THREE PLANE GEOMETRIC GEOID SURFACES for ORTHOMETRIC HEIGHT MODELLING in KAMPALA, UGANDA Bruno Kyamulesire, Paul Dare Oluyori, Eteje S

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THREE PLANE GEOMETRIC GEOID SURFACES FOR ORTHOMETRIC HEIGHT MODELLING IN KAMPALA, UGANDA Bruno Kyamulesire, Paul Dare Oluyori, Eteje S. O. To cite this version: Bruno Kyamulesire, Paul Dare Oluyori, Eteje S. O.. COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THREE PLANE GEOMETRIC GEOID SURFACES FOR ORTHOMETRIC HEIGHT MODELLING IN KAMPALA, UGANDA. FUDMA Journal of Sciences, Federal University Dutsin-Ma, 2020, 4 (3), pp.48-51. 10.33003/fjs-2020-0403-255. hal-02956662 HAL Id: hal-02956662 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02956662 Submitted on 3 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial| 4.0 International License COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF… FUDMA Journal of SciencesKyamulesir (FJS) et al FJS ISSN online: 2616-1370 ISSN print: 2645 - 2944 Vol. 4 No. 3, September, 2020, pp 48 – 51 DOI: https://doi.org/10.33003/fjs-2020-0403-255 COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THREE PLANE GEOMETRIC GEOID SURFACES FOR ORTHOMETRIC HEIGHT MODELLING IN KAMPALA, UGANDA *1Kyamulesire, B., 2Oluyori, P. D. and 3Eteje, S. O. 1Associated Mapping Professionals, P. O. Box 5309, Jinja, Uganda 2P. D. Horvent Surveys Ltd, Abuja Nigeria 3Eteje Surveys and Associates, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The conversion of theoretical, as well as geometric heights to practical heights requires the application of geoidal undulations from a geoid model. -

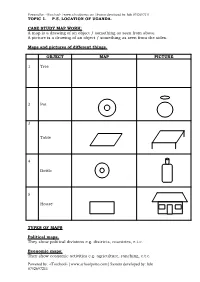

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Sustainable Utilisation of Energy and Biodiversity Resources for Wealth Creation and Development’, 10–13 March 2009, Kampala, Uganda

International Roundtable on ‘Sustainable Utilisation of Energy and Biodiversity Resources for Wealth Creation and Development’, 10–13 March 2009, Kampala, Uganda. Introduction The increasing population pressure and demand for a better life style have necessitated a need for greater use of energy. This has resulted in mounting pressure on the use of available resources which is now mostly met by fossil fuels. The rate of energy consumption is much higher than it was ever before and the demand is on increase. There is a negative balance between source depletion and replenishment by natural processes. This has also resulted in uncontrollable rise in pollution due to air, water, soil and noise besides electro-pollution, causing the very survival of life difficult on Planet Earth. An increase in the level of carbon dioxide, possibly causing a temperature rise leading to global warming and subsequent melting of glaciers culminating into climate change is a phenomenon of utmost concern. This has serious economic and social implications. Climate change linked to emissions is then about limiting growth, and also sharing growth among nations which has its economic overtones. The emerging scenario has led to a tremendous pressure on survival of species type (both plants and animals). The number of such species is registering a significant decline, thereby posing a serious threat to the sustainability of ecosystem itself. A demand for green energy is understood but the quantum and nature of its exploitation remains to be settled. Solar, the ultimate source of energy is now widely discussed, though increase in its efficiency usage is still a matter of continued investigation. -

"Women's Secrets" Among the Baganda

Feature article • 9 • Eroticism, sensuality and “women's secrets” among the Baganda: A critical analysis Sylvia Tamale1 Introduction Sexuality is intricately linked to practically every aspect of our lives: to pleasure, power, politics and procreation, but also to disease, violence, war, language, social roles, religion, kinship structures, identity, creativity… the list is endless. The connection and collision between human sexuality,2 power and politics pro- vided the major inspiration for this piece of research. Specifically, I wanted to explore the various ways in which the erotic is used both as an oppressive and empowering resource. In her compelling essay sub-titled The Erotic as Power, Audre Lorde (1984) argues for the construction of the erotic as the basis of women's resistance against oppression. For her, the concept entailed much more than the sexual act, connecting meaning and form, infusing the body and the psyche. Before Lorde, Michel Foucault (1977; 1990) had demonstrated how the human body is a central component in the operation of power. He theorised the body as “an inscribed surface of invents” from which the prints of history can be read (Rabinow, 1984: 83). In a bid to gain a better understanding of African women's sexuality, this article focuses on one particular cultural/sexual initiation institution among the Baganda3 of Uganda, namely the Ssenga.4 When one speaks of “ensonga za Ssenga” (Ssenga matters) among the Baganda, this is at once understood to signify an institution that has persisted and endured through centuries as a tra- dition of sexual initiation. At the helm of this elaborate socio-cultural institution is the paternal aunt (or surrogate versions thereof), whose role is to tutor young girls and women in a wide range of sexual matters, including pre-menarche practices, pre-marriage preparation, erotic instruction and reproduction. -

A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884

Peripheral Identities in an African State: A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884 Aidan Stonehouse Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Ph.D The University of Leeds School of History September 2012 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor Shane Doyle whose guidance and support have been integral to the completion of this project. I am extremely grateful for his invaluable insight and the hours spent reading and discussing the thesis. I am also indebted to Will Gould and many other members of the School of History who have ably assisted me throughout my time at the University of Leeds. Finally, I wish to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council for the funding which enabled this research. I have also benefitted from the knowledge and assistance of a number of scholars. At Leeds, Nick Grant, and particularly Vincent Hiribarren whose enthusiasm and abilities with a map have enriched the text. In the wider Africanist community Christopher Prior, Rhiannon Stephens, and especially Kristopher Cote and Jon Earle have supported and encouraged me throughout the project. Kris and Jon, as well as Kisaka Robinson, Sebastian Albus, and Jens Diedrich also made Kampala an exciting and enjoyable place to be. -

Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda, In: Africa Spectrum, 49, 3, 29-54

Africa Spectrum Quinn, Joanna R. (2014), Tradition?! Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda, in: Africa Spectrum, 49, 3, 29-54. URN: http://nbn-resolving.org/urn/resolver.pl?urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-7811 ISSN: 1868-6869 (online), ISSN: 0002-0397 (print) The online version of this and the other articles can be found at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of African Affairs in co-operation with the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Uppsala and Hamburg University Press. Africa Spectrum is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To subscribe to the print edition: <[email protected]> For an e-mail alert please register at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Africa Spectrum is part of the GIGA Journal Family which includes: Africa Spectrum ●● Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs ●● Journal of Politics in Latin America <www.giga-journal-family.org> Africa Spectrum 3/2014: 29-54 Tradition?! Traditional Cultural Institutions on Customary Practices in Uganda Joanna R. Quinn Abstract: This contribution traces the importance of traditional institu- tions in rehabilitating societies in general terms and more particularly in post-independence Uganda. The current regime, partly by inventing “traditional” cultural institutions, partly by co-opting them for its own interests, contributed to a loss of legitimacy of those who claim respon- sibility for customary law. More recently, international prosecutions have complicated the use of customary mechanisms within such societies. -

Archives of the Bishop of Uganda

Yale University Library Yale Divinity School Library Archives of the Bishop of Uganda UCU-RG1 Christine Byaruhanga 2007 Revised: 2010-02-03 New Haven, Connecticut Copyright © 2007 by the Yale University Library. Archives of the Bishop of Uganda UCU-RG1 - Page 2 Table of Contents Overview 11 Administrative Information 11 Provenance 11 Information about Access 11 Ownership & Copyright 11 Cite As 11 Historical Note 12 Description of the Papers 12 Arrangement 13 Collection Contents 14 Series I. Administrative/Governing Bodies, 1911-1965 14 Church Missionary Society (CMS) 14 CMS Africa Secretary and General (London), 1955-1961 14 CMS East Africa Volume 1, 1953-1957 15 Dioceses 31 Uganda Diocese 31 Deanery Council Minutes 31 Diocesan Association of the Uganda Diocese 32 Diocesan Boards of the Uganda Diocese 34 Diocesan Council of the Uganda Diocese 35 Upper Nile Diocese 37 Diocesan Council of the Upper Nile Diocese (Book), 1955-1969 37 Diocesan Boards of Finance of the Upper Nile Diocese (Book), 1955-1962 37 Diocese of the Upper Nile 37 Ankole/Kigezi Diocese 39 Rural Deaneries 41 Deanery of Ankole 41 Ankole 41 Mbarara 41 Ecclesiastical Correspondences 42 Buganda 43 Deanery of Buddu 43 Deanery of Bukunja 44 Deanery of Bulemezi 45 Deanery of Busiro 46 Deanery of Bwekula 46 Deanery of Gomba 48 Deanery of Kako 49 Archives of the Bishop of Uganda UCU-RG1 - Page 3 Deanery of Kooki 49 Deanery of Kyagwe 49 Deanery of Mengo 50 Deanery of Ndeje 50 Deanery of Singo 51 Bunyoro 52 Deanery of Bunyoro 52 Busoga 54 Deanery of Busoga 54 Toro/Fort Portal 55 -

Analysis of the Streets of Kampala City to Meet the Needs of Pedestrains: a Case Study of Central Division

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, DESIGN, ART & TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF BUILT ENVIRONMENT DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE & PHYSICAL PLANNING ANALYSIS OF THE STREETS OF KAMPALA CITY TO MEET THE NEEDS OF PEDESTRAINS: A CASE STUDY OF CENTRAL DIVISION OMODING SETH 14/U/14107/PS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE & PHYSICAL PLANNING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING OF MAKERERE UNIVERSITY 2018 i i DEDICATION I dedicate this report first to the Almighty God, who supplied my needs abundantly and gave me the strength, health and sanity to finish it. I also wish to dedicate it to my dearest sister who supported me through my study Miss Tukei Dinah my Parents for their continuous prayer, encouragement and moral support during the research process. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my deepest and most sincere gratitude to my supervisor, for his continuous support and for sacrificing his time to guide and assist me through this development project my project from initial stage to the finish. I would also like to appreciate the Department of Urban and Regional planning lecturers and other lecturers of the Department of Urban and Regional Planning whose input explicated my insight. I would like to appreciate my colleagues, urban and Regional Planning class whose interesting ideas and thoughts made this project a success. Above all, I thank God Almighty, for without his provision, nothing is possible. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION -

Revenue Collection and Service Delivery in Kampala Capital City

REVENUE COLLECTION AND SERVICE DELIVERY IN KAMPALA CAPITAL CITY AUTHORITY (KCCA) BY KASENDWA ROBERT INDEX NO: 2015 / FEB/MSC/M20383/WKD SUPERVISOR: MR. OWINO JOSHUA GEOPELLINI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO SCHOOL OF BUSINESS ADMINISTARTION IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF SCIENCES IN ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE OF NKUMBA UNIVERSITY i OCTOBER 2018 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my original work and has never been submitted to any other university / institution for any award. Signature………………………………………… Candidate’s name: KASENDWA ROBERT Date………………………………………………. ii APPROVAL This dissertation has been carried out under my supervision and is submitted for the award of a degree of Master of Science in Accounting and Finance with my approval as the candidates’ supervisor. Signature…………………………………… Mr. Owino Joshua Geopellini (Supervisor) Date………………………………………… iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents and friends who tirelessly stood with me during my study. I also dedicate this dissertation to my wife and children who dearly missed me during the course of preparation of this piece of work. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Firstly, I would like to thank and give glory to God for the inspiration and strength He granted me throughout this work in spite of all the difficulties encountered. I am so grateful to my supervisor Mr. Owino Joshua Geopellini for his overwhelming guidance and support through this work despite his busy schedules at the University. I am also grateful to my family members (parents, brothers, sisters and all others), friends and course mates for their maximum cooperation they showed me during the course of this research and my studies.