Young Soul Rebels? Soul Scenes in Seventies Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

RHYTHM & BLUES...63 Order Terms

5 COUNTRY .......................6 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................71 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............22 SURF .............................83 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......23 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............85 WESTERN..........................27 PSYCHOBILLY ......................89 WESTERN SWING....................30 BRITISH R&R ........................90 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................30 SKIFFLE ...........................94 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................31 AUSTRALIAN R&R ....................95 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........31 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............96 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND....31 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE......32 POP.............................103 COUNTRY CHRISTMAS................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................136 BLUEGRASS ........................33 LATIN ............................148 NEWGRASS ........................35 JAZZ .............................150 INSTRUMENTAL .....................36 SOUNDTRACKS .....................157 OLDTIME ..........................37 EISENBAHNROMANTIK ...............161 HAWAII ...........................38 CAJUN/ZYDECO ....................39 DEUTSCHE OLDIES ..............162 TEX-MEX ..........................39 KLEINKUNST / KABARETT ..............167 FOLK .............................39 Deutschland - Special Interest ..........167 WORLD ...........................41 BOOKS .........................168 ROCK & ROLL ...................43 BOOKS ...........................168 REGIONAL R&R .....................56 DISCOGRAPHIES ....................174 LABEL R&R -

BTN6916 LMW NORTHERN SOUL ENTS GUIDE SK.Indd

22-25 SEPT 2017 20-23 SEPT 2019 SKEGNESS RESORT GLORIACELEBRATING 60 YEARS JONES OF MOTOWN BOBBY BROOKS WILSON BRENDA HOLLOWAY EDDIE HOLMAN CHRIS CLARK THE FLIRTATIONS TOMMY HUNT THE SIGNATURES FT. STEFAN TAYLOR PAUL STUART DAVIES•JOHNNY BOY PLUS MANY MORE WELCOME TO THE HIGHLIGHTS As well as incredible headliners and legendary DJs, there are loads WORLD’S BIGGEST AND more soulful events to get involved in: BEST NORTHERN SOUL ★ Dance competition with Russ Winstanley and Sharon Sullivan ★ Artist meet and greets SURVIVORS WEEKENDER ★ Shhhh... Battle of the DJs Silent Disco ★ Tune in to Northern Soul BBC – Butlin’s Broadcasting Company Original Wigan Casino jock and founder of the Soul Survivors Weekender, with Russ! Russ Winstanley, has curated another jam-packed few days for you. It’s an ★ incredible line-up with soul legends fl own in from around the world plus a Northern Soul Awards and Dance Competition host of your favourite soul spinners. We’re celebrating Motown Records 60th Anniversary in 2019. To mark this special occasion we have some of the original Motown ladies gracing the stage to celebrate this milestone birthday. SATURDAY 14.00 REDS Meet and Greet with Eddie Holman, Bobby Brooks Wilson, Tommy Hunt Brenda Holloway, Chris Clark and Gloria Jones will also be joining us for a Q&A session, together with Motown afi cionado, Sharon Davies, on Sunday afternoon in Reds. Not to be missed!! SUNDAY 14.00 REDS Don’t miss the Northern Soul dance classes, DJ Battles, Northern Soul Q&A with Brenda Holloway, Chris Clark, Gloria Jones and Sharon Davis awards and dance competitions across the weekend and be sure to look Hosted by Russ Winstanley and Ian Levine, followed by a meet and greet out for limited edition, souvenir vinyl and merch in the Skyline record stall. -

Record-Business-1982

INSIDE Singles chart, 6-7; Album chart, 17; New Singles, 18; New Albums 9; Airplay guide, 14-15; Independent Labels, 8; Country Music Focus,12-13. April 5, 1982 VOLUME FIVENumber 2 65p 56 staff given Record wholesalers' notice at EMI's video success story World Records IN STARK contrast to their retailing area of business. "It will never take mail order co. counterparts record wholesalers areover the record side and we wouldn't leading the move into video and mostwant it to but it is a valuable line," said WORLD RECORDS, EMI'smail are well placed to take advantage of theBrian Yershon, video marketing man- order arm, will be sold or merged with expected boom. ager. another direct mail company within the While the video -only wholesalers "In 1982 we are primarily a record next few months. eye the horizon with some trepidationwholesaler but we seefiveyears The company, which began 25 years the record/video outfits, particularlygrowth in the video industry. We are ago, was moved out of its Richmond the big four - Wynd-Up, Terry Blood,seeing growth on both sides and I think offices last year and re -settled at the S. Gold & Sons and Warrens - arethat records and videos are natural main EMI factory complex at Uxbridge looking for growth. bedfellows," said Colin Reilly, Wynd- Road, Hayes. The 56 staff were told last All these companies plus LightningUp chief executive. As a main board week that talks were taking place with (whose recent name change to Light-director of NSS he is also sure that other companies interested in either ning Records & Video indicates itsvideo is a promising retail growth area. -

Benny Page to Release New Single Champion Sound

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BENNY PAGE TO RELEASE NEW SINGLE CHAMPION SOUND Artist: Benny Page Release: Champion Sound ft. Assassin Date: August 2014 “If you don't know about Benny Page…make sure you get to know.... We are loving the sound of this” MOBO Awards (Official) “Benny Page is going to be a complete tear down” Glastonbury Festivals “This tune is massive!” BBC Radio One In the lead up to his debut Glastonbury Festival appearance headlining The Cave, Benny Page announces his new single entitled Champion Sound, out worldwide August 2014 on his own label High Culture Recordings and Rise Artists Ltd. This release is revealed after Mistajams recent BBC Radio premiere, an accolade following the wave of success surrounding his recent dancefloor hit Hot Body Gal ft. Richie Loop supported Sir David Rodigan, Seani B and Toddla T across BBC Radio One, 1Xtra and Kiss Fm alongside worldwide festival and club appearances. Champion Sound features Assassin who appears on Kanye West’s last album “Yeezus” and was mastered at Metropolis Studios by Stuart Hawkes who has worked with Basement Jaxx, Rudimental, Disclosure, Example and Maverick Sabre to name a few. After number of years establishing international recognition; Benny Page has honed his sound initiating the start of this unique album project. Flying over to Jamaica to work personally with prestigious artists in the area, Benny Page teamed up with Richie Loop on his first single for the project entitled Hot Body Gal, the follow up Champion Sound also features a Jamaican front man called Assassin. He recorded a range of artists on the island with a goal to achieve a more authentic and diverse sound, going through the motions of a more traditional and personal songwriting process managing the studio recordings directly. -

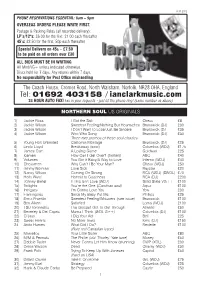

Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1

Clarky List 51_Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1 JULY 2012 PHONE RESERVATIONS ESSENTIAL : 8am – 9pm OVERSEAS ORDERS PLEASE WRITE FIRST. Postage & Packing Rates (all recorded delivery): LP’s/12"s: £6.00 for the first, £1.00 each thereafter 45’s: £2.50 for the first, 50p each thereafter Special Delivery on 45s – £7.50 to be paid on all orders over £30 ALL BIDS MUST BE IN WRITING All Mint/VG+ unless indicated otherwise. Discs held for 7 days. Any returns within 7 days. No responsibility for Post Office mis han dling The Coach House, Cromer Road, North Walsham, Norfolk, NR28 0HA, England Tel: 01692 403158 / ianclarkmusic.com 24 HOUR AUTO FAX! Fax in your requests - just let the phone ring! (same number as above) NORTHERN SOUL US ORIGINALS 1) Jackie Ross I Got the Skill Chess £8 2) Jackie Wilson Sweetest Feeling/Nothing But Heartaches Brunswick (DJ) £30 3) Jackie Wilson I Don’t Want to Lose/Just Be Sincere Brunswick (DJ £35 4) Jackie Wilson Who Who Song Brunswick (DJ) £30 Three rare promos of these soul classics 5) Young Holt Unlimited California Montage Brunswick (DJ) £25 6) Linda Lloyd Breakaway (swol) Columbia (WDJ) £175 7) James Carr A Losing Game Goldwax £25 8) Icemen How Can I Get Over? (brilliant) ABC £40 9) Volumes You Got it Baby/A Way to Love Inferno (WDJ) £40 10) Chessmen Why Can’t I Be Your Man? Chess (WDJ) £50 11) Jimmy Norman Love Sick Raystar £20 12) Nancy Wilcox Coming On Strong RCA (WDJ) (SWOL) £70 13) Herb Ward Honest to Goodness RCA (DJ) £200 14) Johnny Bartel If This Isn’t Love (WDJ) Solid State VG++ £100 15) Twilights -

Soul Top 1000

UUR 1: 14 april 9 uur JAAP 1000 Isley Brothers It’s Your Thing 999 Jacksons Enjoy Yourself 998 Eric Benet & Faith Evans Georgy Porgy 997 Delfonics Ready Or Not Here I Come 996 Janet Jackson What Have Your Done For Me Lately 995 Michelle David & The Gospel Sessions Love 994 Temptations Ain’t Too Proud To Beg 993 Alain Clark Blow Me Away 992 Patti Labelle & Michael McDonald On My Own 991 King Floyd Groove Me 990 Bill Withers Soul Shadows UUR 2: 14 april 10 uur NON-STOP 989 Michael Kiwanuka & Tom Misch Money 988 Gloria Jones Tainted Love 987 Toni Braxton He Wasn’t Man Enough 986 John Legend & The Roots Our Generation 985 Sister Sledge All American Girls 984 Jamiroquai Alright 983 Carl Carlton She’s A Bad Mama Jama 982 Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings Better Things 981 Anita Baker You’re My Everything 980 Jon Batiste I Need You 979 Kool & The Gang Let’s Go Dancing 978 Lizz Wright My Heart 977 Bran van 3000 Astounded 976 Johnnie Taylor What About My Love UUR 3: 14 april 11 uur NON-STOP 975 Des’ree You Gotta Be 974 Craig David Fill Me In 973 Linda Lyndell What A Man 972 Giovanca How Does It Feel 971 Alexander O’ Neal Criticize 970 Marcus King Band Homesick 969 Joss Stone Don’t Cha Wanna Ride 1 968 Candi Staton He Called Me Baby 967 Jamiroquai Seven Days In Sunny June 966 D’Angelo Sugar Daddy 965 Bill Withers In The Name Of Love 964 Michael Kiwanuka One More Night 963 India Arie Can I Walk With You UUR 4: 14 april 12 uur NON-STOP 962 Anthony Hamilton Woo 961 Etta James Tell Mama 960 Erykah Badu Apple Tree 959 Stevie Wonder My Cherie Amour 958 DJ Shadow This Time (I’m Gonna Try It My Way) 957 Alicia Keys A Woman’s Worth 956 Billy Ocean Nights (Feel Like Gettin' Down) 955 Aretha Franklin One Step Ahead 954 Will Smith Men In Black 953 Ray Charles Hallelujah I Love Her So 952 John Legend This Time 951 Blu Cantrell Hit' m Up Style 950 Johnny Pate Shaft In Africa 949 Mary J. -

Dec. 22, 2015 Snd. Tech. Album Arch

SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) Affinity-Affinity S=Trident Studio SOHO, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R=1970 (Vertigo) E=Frank Owen, Robin Geoffrey Cable P=John Anthony SOURCE=Ken Scott, Discogs, Original Album Liner Notes Albion Country Band-Battle of The Field S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Island Studio, St. Peter’s Square, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=1973 (Carthage) E=John Wood P=John Wood SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Albion Dance Band-The Prospect Before Us S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (PARTIALLY TRACKED. MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Olympic Studio #1 Studio, Barnes, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=Mar.1976 Rel. (Harvest) @ Sound Techniques, Olympic: Tracks 2,5,8,9 and 14 E= Victor Gamm !1 SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) P=Ashley Hutchings and Simon Nicol SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Alice Cooper-Muscle of Love S=Sunset Sound Recorders Hollywood, CA. Studio #2. (TRACKED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Record Plant, NYC, A&R Studio NY (OVERDUBS AND MIX) R=1973 (Warner Bros) E=Jack Douglas P=Jack Douglas and Jack Richardson SOURCE: Original Album liner notes, Discogs Alquin-The Mountain Queen S= De Lane Lea Studio Wembley, London (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R= 1973 (Polydor) E= Dick Plant P= Derek Lawrence SOURCE: Original Album Liner Notes, Discogs Al Stewart-Zero She Flies S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

Smash Hits Volume 60

35p USA $1 75 March I9-April 1 1981 W I including MIND OFATOY RESPECTABLE STREE CAR TROUBLE TOYAH _ TALKING HEADS in colour FREEEZ/LINX BEGGAR &CO , <0$& Of A Toy Mar 19-Apr 1 1981 Vol. 3 No. 6 By Visage on Polydor Records My painted face is chipped and cracked My mind seems to fade too fast ^Pg?TF^U=iS Clutching straws, sinking slow Nothing less, nothing less A puppet's motion 's controlled by a string By a stranger I've never met A nod ofthe head and a pull of the thread on. Play it I Go again. Don't mind me. just work here. I don't know. Soon as a free I can't say no, can't say no flexi-disc comes along, does anyone want to know the poor old intro column? Oh, no. Know what they call me round here? Do you know? The flannel panel! The When a child throws down a toy (when child) humiliation, my dears, would be the finish of a more sensitive column. When I was new you wanted me (down me) Well, I can see you're busy so I won't waste your time. I don't suppose I can drag Now I'm old you no longer see you away from that blessed record long enough to interest you in the Ritchie (now see) me Blackmore Story or part one of our close up on the individual members of The Jam When a child throws down a toy (when toy) (and Mark Ellen worked so hard), never mind our survey of the British funk scene. -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979.