Seeking and Refugee Children: a Study in a Single School in Kent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Active Lives Children and Young People Survey: Summer 2021 Selected Schools

Active Lives Children and Young People Survey: Summer 2021 Selected Schools Local Authority Name School Name Type of Establishment Ashford Highworth Grammar School Secondary Ashford Mersham Primary School Primary Ashford Tenterden Church of England Junior School Primary Ashford Towers School and Sixth Form Centre Secondary Ashford Wittersham Church of England Primary School Primary Canterbury Junior King's School Primary Canterbury Simon Langton Grammar School for Boys Secondary Canterbury St Anselm's Catholic School, Canterbury Secondary Canterbury St Peter's Methodist Primary School Primary Canterbury The Whitstable School Secondary Canterbury Whitstable Junior School Primary Canterbury Wincheap Foundation Primary School Primary Dartford Knockhall Primary School Primary Langafel Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary Dartford School Primary Dartford Longfield Academy Secondary Dartford Stone St Mary's CofE Primary School Primary Dartford Wilmington Grammar School for Boys Secondary Dover Charlton Church of England Primary School Primary Dover Dover Christ Church Academy Secondary Dover Dover Grammar School for Girls Secondary Dover Eastry Church of England Primary School Primary Dover Whitfield Aspen School Primary Folkestone and Hythe Cheriton Primary School Primary Folkestone and Hythe Lyminge Church of England Primary School Primary Folkestone and Hythe St Nicholas Church of England Primary Academy Primary Folkestone and Hythe The Marsh Academy Secondary Gravesham King's Farm Primary School Primary Gravesham Northfleet Technology -

St George's Church of England Foundation School

ST GEORGE’S CHURCH OF ENGLAND FOUNDATION SCHOOL “Every moment, every day, every individual counts” Primary: Hope Way, Broadstairs, Kent CT10 2FR Secondary: Westwood Road, Broadstairs, Kent CT10 2LH Telephone: 01843 861696 Email: [email protected] website: www.stgeorges-school.org.uk Monday, 13th January 2020 Dear Parents RE: Kent Test Information During Term 6, parents who wish for their child to sit the Kent Test will be required to register their child to sit the test. This year the registration window will open from Wednesday, 3rd June until Friday, 3rd July 2020. This process must be completed by parents online. Information will be sent home nearer to the time. For your information, children in Year 6 this year sat the Kent Test on 12th September 2019. An Information Evening outlining the Process for Entry to Secondary Education (PESE) will take place on Thursday, 12th March at 6.00pm in the Primary School Hall. Parent Consultations are being held on Wednesday 25th and Thursday 26th March. You will have received your child’s CATs scores already and these will help in your decision making as to whether you will register your child for the Kent Test. There will be an opportunity to meet with Mrs Curry to discuss any queries during Term 5. If you are still unsure whether your child should take the Kent Test remember that the Kent Test is designed to identify the top 25% of the children across Kent. Kent County Council information on the PESE process for September 2020 entry can be found on the following website -

Royal Holloway University of London Aspiring Schools List for 2020 Admissions Cycle

Royal Holloway University of London aspiring schools list for 2020 admissions cycle Accrington and Rossendale College Addey and Stanhope School Alde Valley School Alder Grange School Aldercar High School Alec Reed Academy All Saints Academy Dunstable All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham All Saints Church of England Academy Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Altrincham College of Arts Amersham School Appleton Academy Archbishop Tenison's School Ark Evelyn Grace Academy Ark William Parker Academy Armthorpe Academy Ash Hill Academy Ashington High School Ashton Park School Askham Bryan College Aston University Engineering Academy Astor College (A Specialist College for the Arts) Attleborough Academy Norfolk Avon Valley College Avonbourne College Aylesford School - Sports College Aylward Academy Barnet and Southgate College Barr's Hill School and Community College Baxter College Beechwood School Belfairs Academy Belle Vue Girls' Academy Bellerive FCJ Catholic College Belper School and Sixth Form Centre Benfield School Berkshire College of Agriculture Birchwood Community High School Bishop Milner Catholic College Bishop Stopford's School Blatchington Mill School and Sixth Form College Blessed William Howard Catholic School Bloxwich Academy Blythe Bridge High School Bolton College Bolton St Catherine's Academy Bolton UTC Boston High School Bourne End Academy Bradford College Bridgnorth Endowed School Brighton Aldridge Community Academy Bristnall Hall Academy Brixham College Broadgreen International School, A Technology -

The Kent Model of Career Education and Guidance

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UDORA - University of Derby Online Research Archive Dr Tristram Hooley Head of iCeGS University of Derby The Kent Model of Career Education and Guidance Date: 01/05/2015 Skills & Employability Service 1 Version 5 Education and Young People’s Services The Kent Model of Career Education and Guidance Contents Publication information .......................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 4 Foreword ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Executive summary ................................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Understanding careers policy ............................................................................................................... 10 The new statutory guidance ............................................................................................................. 10 Other key changes ........................................................................................................................... -

Draft LA Report Template

Local Authority Report To The Schools Adjudicator From Kent County Council 30 June 2018 Report Cleared by: Keith Abbott - Director of Education Planning and Access Date submitted: 28th June 2018 By : Scott Bagshaw – Head of Fair Access Contact email address: [email protected] Telephone number: 03000 415798 www.gov.uk/government/organisations/office-of-the-schools-adjudicator Please email your completed report to: [email protected] by 30 June 2018 and earlier if possible 1 Introduction Section 88P of the School Standards and Framework Act 1998 (the Act) requires every local authority to make an annual report to the adjudicator. The Chief Adjudicator then includes a summary of these reports in her annual report to the Secretary for State for Education. The School Admissions Code (the Code) sets out the requirements for reports by local authorities in paragraph 6. Paragraph 3.23 specifies what must be included as a minimum in the report to the adjudicator and makes provision for the local authority to include any other issues. The report must be returned to the Office of the Schools Adjudicator by 30 June 2018. The report to the Secretary of State for 2017 highlighted that at the normal points of admission the main admissions rounds for entry to schools work well. The Chief Adjudicator expressed less confidence that the needs of children who need a place outside the normal admissions rounds were so well met. In order to test this concern, local authorities are therefore asked to differentiate their answers in this year’s report between the main admissions round and in year admissions1. -

The Kent Science and Technology Challenge Day for Gifted and Talented Year 8 and Year 9S

The Kent Science and Technology Challenge Day for Gifted and Talented Year 8 and Year 9s What are the Science & Technology Days for? How are they rated? They raise enthusiasm for STEM subjects and encour- Evaluations of last year’s events indicated that…. age young people to consider studying them further. 99% of the teachers and 83% of the young people con- In 2015, MCS Projects Ltd organised 42 Challenge Days sidered their Day to have been ‘good’ or ‘very good’. across the UK, involving more than 300 schools. 73% of the young people were more likely to consider What happens? studying STEM subjects at college or university as a result of the event. Twelve Gifted and Talented Year 8/9s are invited to participate from each school. Working together in mixed school teams of four, they undertake practical activities that increase their awareness of the applica- tion of science. Each activity is designed to develop skills that will be needed in the workplace, with marks being awarded for planning, team work and the finished product. Challenge Days are usually held on the campus of a local college or university. The young people undertake three 75min activities. The local Mayor or Deputy Lieu- The overall winning teams from each Challenge Day tenant is invited to present awards to members of each progress to one of our regional Finals. In 2015, the winning team. Finals were hosted by the Universities of Cambridge, Manchester and Sheffield. Director: P.W.Waterworth 12 Edward Terrace, Sun Lane, Alresford, Hampshire SO24 9LY Registered in England: No 4960377 • VAT Reg. -

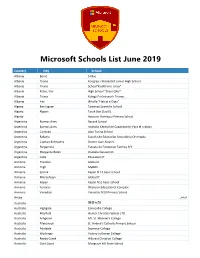

Microsoft Schools List June 2019

Microsoft Schools List June 2019 Country City School Albania Berat 5 Maj Albania Tirane Kongresi i Manastirit Junior High School Albania Tirane School"Kushtrimi i Lirise" Albania Patos, Fier High School "Zhani Ciko" Albania Tirana Kolegji Profesional i Tiranës Albania Fier Shkolla "Flatrat e Dijes" Algeria Ben Isguen Tawenza Scientific School Algeria Algiers Tarek Ben Ziad 01 Algeria Azzoune Hamlaoui Primary School Argentina Buenos Aires Bayard School Argentina Buenos Aires Instituto Central de Capacitación Para el Trabajo Argentina Cordoba Alan Turing School Argentina Rafaela Escuela de Educación Secundaria Orientada Argentina Capitan Bermudez Doctor Juan Alvarez Argentina Pergamino Escuela de Educacion Tecnica N°1 Argentina Margarita Belen Graciela Garavento Argentina Caba Educacion IT Armenia Hrazdan Global It Armenia Tegh MyBOX Armenia Syunik Kapan N 13 basic school Armenia Mikroshrjan Global IT Armenia Kapan Kapan N13 basic school Armenia Yerevan Ohanyan Educational Complex Armenia Vanadzor Vanadzor N19 Primary School الرياض Aruba Australia 坦夻易锡 Australia Highgate Concordia College Australia Mayfield Hunter Christian School LTD Australia Ashgrove Mt. St. Michael’s College Australia Ellenbrook St. Helena's Catholic Primary School Australia Adelaide Seymour College Australia Wodonga Victory Lutheran College Australia Reedy Creek Hillcrest Christian College Australia Gold Coast Musgrave Hill State School Microsoft Schools List June 2019 Country City School Australia Plainland Faith Lutheran College Australia Beaumaris Beaumaris North Primary School Australia Roxburgh Park Roxburgh Park Primary School Australia Mooloolaba Mountain Creek State High School Australia Kalamunda Kalamunda Senior High School Australia Tuggerah St. Peter's Catholic College, Tuggerah Lakes Australia Berwick Nossal High School Australia Noarlunga Downs Cardijn College Australia Ocean Grove Bellarine Secondary College Australia Carlingford Cumberland High School Australia Thornlie Thornlie Senior High School Australia Maryborough St. -

Empowering Young People in More Communities to Reach Their Full Potential a Year in Review Team Highlights

ANNUAL REVIEW 2017 EMPOWERING YOUNG PEOPLE IN MORE COMMUNITIES TO REACH THEIR FULL POTENTIAL A YEAR IN REVIEW TEAM HIGHLIGHTS CHARLIE GREEN, CHAIR AND KENT My role is about making sure KEVIN MUNDAY, CEO ThinkForward young people in NICOLETTE, EDUCATION Kent get to experience the careers 2017 WAS THE YEAR AND EMPLOYMENT they’re interested in. WE LAUNCHED IN COORDINATOR I also arrange enrichment activities to broaden horizons and improve confidence. OUR THIRD LOCATION Exposure to the workplace and taking part AND STRENGTHENED in new activities open their eyes and help them understand what they need to do to achieve EXISTING PARTNERSHIPS their goals. For me, this was the attraction of ThinkForward’s vision is moving from teaching to ThinkForward. I’m simple – to prevent a new now able to focus full-time on helping students generation of youth find a career and start building their lives. unemployment. We do this through a coaching programme that provides long-term support LONDON A highlight for me in 2017 was to young people at high risk of seeing my students graduate unemployment. At the end CHARLENE, COACH AND from ThinkForward. of 2016 we set out ambitious PROGRAMME ADVISOR One young person’s journey particularly plans to do this more widely, sticks out because I was able to help her by refining our coaching when she was struggling to get into programme, diversifying university. After a bit of a battle she’s now funding and scaling up delivery. studying social work at Canterbury. I’ve In the context of constrained been a coach for five years and I’ve learned public finances, continued a lot about what works so I’m now going to changes to educational policy be putting my knowledge to use by taking and the distractions of Brexit an organisational lead on developing our looming over many employers, programme design. -

Secondary School Application Guidance 2020-2021

Garlinge Primary School and Nursery 21st September 2020 Year 6 Secondary School Admission Guide 2020 - 2021 Dear Parents and Carers, Under usual circumstances, at around this time of year, I would usually hold a meeting for parents and carers of pupils in year 6 in order to support you in the process whereby you would select and apply for a place at a local secondary school. Unfortunately, under the current restrictions, we are unable to hold a large meeting, but we hope the information in this letter will give you some support with the process, should it be needed. All parents of children in year 6 will need to complete the Secondary Common Application Form (SCAF) to apply for their preferred secondary school. The closing date this year is midnight on the 2nd November 2020. This year, parents will be able to name up to six schools in order of preference on their list; this is an increase from four schools in previous years. This is because parents will not know their child’s Kent Test results before applications need to be submitted. As an initial line of enquiry, I would strongly recommend visiting secondary school websites, which will help to give you the information on the school and the admissions process. Do investigate all of our local schools and read their selection criteria. This will then help you to consider if your child would be happy at the school. Most schools have an admissions section, as well as an admission email contact. Schools are also beginning to prepare virtual tours this year for prospective students and their parents to visit. -

2019 Transfer to Secondary School School Admission Appeals

Please return your appeal form by 29 March 2019 2019 Transfer to Secondary School School Admission Appeals A Guide for Parents This guide is to help families who have not got a place at the secondary school they wanted. If you are disappointed and worried about where your child will go to school in September, this guide will answer some of your questions and explain what you can do next. In the first instance you should visit the school you have been offered to get a feel for it and meet with the headteacher. Once you have done this, if you are still not satisfied you may want to consider lodging an appeal for your preferred school(s). www.kent.gov.uk/schooladmissions Why didn’t my child get a place at the school I wanted? The County Council will have tried to offer a place at the school you wanted. If that hasn’t happened it’s probably because the school had more applications than places available and other children had a higher priority for the place than your child. It may also be because your child did not meet the entry requirements for the school and so could not be offered a place. What does this mean? When a school doesn’t have enough places for everyone who wants to go there, it has to have a way of deciding which children should get in. Often a school takes the children who live closest first, so if you live further away, it may have filled all its places with children who live nearer. -

Hartsdown Academy Admissions Criteria 2022-2023

Admissions Arrangements 2022 – 2023 Secondary Transfer All applications must be made via Kent Admissions. All details on how to complete applications will be found in the “Admission to Secondary School in Kent” brochure or on the KCC website: www.kent.gov.uk/schooladmissions. Hartsdown Academy has a Published Admissions Number (PAN) or intake number for each year group of 180. in which children are normally admitted to the school. Once all applications have been received, they will be sent to the school to rank in priority order, as per the oversubscription criteria below: Oversubscription Criteria If the number of preferences for the school is more than the number of places available, places will be allocated in the following priority order – 1. Statement of Special Educational Needs/Education, Health and Care Plan - before the application of oversubscription criteria, children with a Statement of Special Educational Need or Education, Health and Care Plan which names the school will be admitted. As a result of this, the published admissions number will be reduced accordingly. 2. Children in Local Authority Care –a child under the age of 18 years for whom the local authority provides accommodation by agreement with their parents/carers (Section 22 of the Children Act 1989) or who is the subject of a care order under Part IV of the Act. This applies equally to children who immediately after being looked after by the local authority became subject to an adoption, residence or special guardianship order. (As defined by Section 46 of the Adoption and Children Act 2002 or Section 8 or 14A of the Children Act 1989). -

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2020 Contents

The UK’s European university ANNUAL REVIEW / FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2020 Contents 1 Introduction by the Vice-Chancellor and President 2 Highlights of the year 5 Membership of Council 6 Principal Officers 8 University public benefit statement 16 Strategic Report 32 Statement of corporate governance & internal control 36 Statement of the responsibilities of the University’s Council 37 Report of the independent auditors to the Council of the University of Kent 39 Financial Statements 39 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income and expenditure 40 Statement of changes in reserves 41 Consolidated statement of financial position 42 Consolidated statement of cashflows 43 Statement of principal accounting policies 48 Notes to the accounts 70 Awards, appointments, promotions & deaths www.kent.ac.uk 1 INTRODUCTION I am pleased to introduce this year’s annual review which covers what has possibly been one of the most challenging periods in the University’s history. Everyone has been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, of course. However, I want to pay a huge tribute here to the University’s staff and students who have had to adjust to extremely testing circumstances. Over the space of a few weeks we had to change the way that we deliver our teaching; arrange a new system of online exams; and switch our working methods to enable the majority of staff to work from home and ensure that those who were required to work at the university were as safe and secure as we could possibly arrange. At the same time, many of our staff, both academic and professional have been making substantial contributions to the national efforts to respond to Covid-19 – from supplying PPE to engaging in cutting edge research.