Persistence of Female Genital Mutilation in Rural Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Report of Yellow Fever Cases in 14 States Serial Number 010: Epi-Week 4 (As at 29 January 2021)

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Report of Yellow fever Cases in 14 States Serial Number 010: Epi-Week 4 (as at 29 January 2021) HIGHLIGHTS ▪ The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) is currently responding to reports of yellow fever cases in 14 states - Akwa Ibom, Bauchi, Benue, Borno, Delta, Ebonyi, Enugu, Gombe, Imo, Kogi, Osun, Oyo, Plateau and Taraba States From the 14 States ▪ In the last week (weeks 4, 2021) ‒ Four new confirmed cases were reported from National Reference Laboratory (NRL) from 2 Local Government Areas (LGAs) in Benue - [Okpokwu (3), Ado (1) ‒ Thirteen presumptive positive cases were reported from NRL [Benue (6)] and Central Public Health Laboratory (CPHL) from [Enugu (6), Oyo (1)] ‒ One new LGA reported a confirmed case from Ado (1) in Benue State, ‒ No new death was recorded among confirmed cases ▪ Cumulatively from epi-week 24, 2020 – epi-week 4, 2021 ‒ A total of 1,502 suspected cases with 179 presumptive positive cases have been reported from 34 LGAs across 14 States from the Nigeria Laboratories ‒ Out of the 1,502 suspected, 161 confirmed cases [Delta-63 Ika North-East (48), Aniocha-South(6), Ika South (4), Oshimili South (2), Oshimili North(1), Ukwuani(1), Ndokwa West (1)], [Enugu-53 Enugu East (4), Enugu North (1), Igbo-Etiti (6), Igbo-Eze North(13), Isi-Uzo (15), Nkanu West (3) Nsukka(8), Udenu (3)], [Benue-17 (Ogbadibo (12), Okpokwu (4), Ado (1)], [Bauchi-9 Ganjuwa (8), Darazo (1)], [Borno-6 Gwoza(1), Hawul (1), Jere (2), Shani (1), Maiduguri (1)], [Ebonyi-3 Ohaukwu (3)], [Oyo-3), Ibarapa North East (1), Ibarapa North (2)], [Gombe-1 Akko (1)], [Imo-1 Owerri North(1)], [Kogi-1 Lokoja (1)], [Plateau- 1 Langtang North (1)], [Taraba-1 Jalingo (1)], [Akwa Ibom-1 Uyo(1)] and [Osun-1 Ilesha East (1)]. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Assessment of Youths Involvement in Self-Help Community Development Projects in Nsukka Local Government Area of Enugu State By

i ASSESSMENT OF YOUTHS INVOLVEMENT IN SELF-HELP COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS IN NSUKKA LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF ENUGU STATE BY EZEMA MARCILLINUS CHIJIOKE PG/M.ED/11/58977 DEPARTMENT OF ADULT EDUCATION AND EXTRA-MURAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA AUGUST, 2014. 2 ASSESSMENT OF YOUTHS INVOLVEMENT IN SELF-HELP COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS IN NSUKKA LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF ENUGU STATE BY EZEMA MARCILLINUS CHIJIOKE PG/M.ED/11/58977 DEPARTMENT OF ADULT EDUCATION AND EXTRA-MURAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA ASSOC. PROF (MRS.) F.O. MBAGWU (SUPERVISOR) AUGUST, 2014. 3 TITLE PAGE Assessment of Youths Involvement in Self-Help Community Development Projects in Nsukka Local Government Area of Enugu State 4 APPROVAL PAGE This project has been approved for the Department of Adult Education and Extra-Mural Studies University of Nigeria, Nsukka. By _________________ _________________ Assoc. Prof (Mrs) F.O. Mbagwu Prof. P.N.C. Ngwu Supervisor Head of Department _______________ ________________ Internal Examiner External Examiner ________________________ Prof. IK. Ifelunni Dean Faculty of Education 5 CERTIFICATION Ezema M.C is a postgraduate student in the Department of Adult Education and Extra-Mural Studies with Registration Number PG/M.Ed/11/58977 and has satisfactorily completed the requirements for the course and research work for the degree of Masters in Adult Education and Community Development. The work embodied in this project is original and has not been submitted in part or full for any other diploma or degree of this university or any other university. ___________________ ___________________ Ezema, Marcillinus Chijioke Assoc. Prof (Mrs) F.O. Mbagwu Student Supervisor 6 DEDICATION This research work is dedicated to God Almighty for his mercy and protection to me throughout the period of writing this project. -

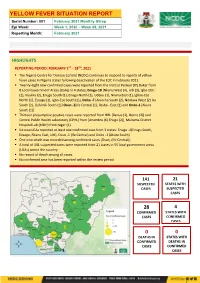

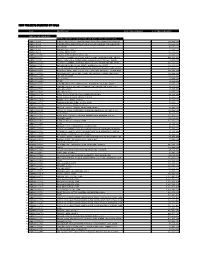

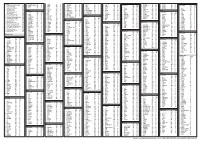

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Serial Number: 001 February 2021 Monthly Sitrep Epi Week: Week 1, 2020 – Week 08, 2021 Reporting Month: February 2021

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Serial Number: 001 February 2021 Monthly Sitrep Epi Week: Week 1, 2020 – Week 08, 2021 Reporting Month: February 2021 HIGHLIGHTS REPORTING PERIOD: FEBRUARY 1ST – 28TH, 2021 ▪ The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) continues to respond to reports of yellow fever cases in Nigeria states following deactivation of the EOC in February 2021. ▪ Twenty -eight new confirmed cases were reported from the Institut Pasteur (IP) Dakar from 8 Local Government Areas (LGAs) in 4 states; Enugu-18 [Nkanu West (4), Udi (3), Igbo-Etiti (2), Nsukka (2), Enugu South (1), Enugu North (1), Udenu (1), Nkanu East (1), Igboe-Eze North (1), Ezeagu (1), Igbo-Eze South (1)], Delta -7 [Aniocha South (2), Ndokwa West (2) Ika South (2), Oshimili South (1)] Osun -2[Ife Central (1), Ilesha - East (1) and Ondo-1 [Akure South (1)] ▪ Thirteen presumptive positive cases were reported from NRL [Benue (2), Borno (2)] and Central Public Health Laboratory (CPHL) from [Anambra (6) Enugu (2)], Maitama District Hospital Lab (MDH) from Niger (1) ▪ Six new LGAs reported at least one confirmed case from 3 states: Enugu -4(Enugu South, Ezeagu, Nkanu East, Udi), Osun -1 (Ife Central) and Ondo -1 (Akure South) ▪ One new death was recorded among confirmed cases [Osun, (Ife Central)] ▪ A total of 141 suspected cases were reported from 21 states in 55 local government areas (LGAs) across the country ▪ No record of death among all cases. ▪ No confirmed case has been reported within the review period 141 21 SUSPECTED STATES WITH CASES SUSPECTED CASES 28 4 -

Break the Silence News!

Break the Silence News! A Monthly Bulleting of Tamar Sexual Assault Referral Centre (SARC) Volume 9 January 2016 - February 2016 Edition participants to help carry out health awareness DFID trains campaign among stakeholders in the various 46 doctors, nurses, counselors and communities in Nigeria through the churches, social workers on rape in Enugu mosques and schools. Also speaking at the event in Enugu, one of the Justice For All (J4A) Programme of the Department trainers/facilitators from Manchester who for International Development (DFID), have begun incidentally is the Centre Manager of St. Mary's the training of 46 medical practitioners and social Sexual Assault Referral Centre, Manchester City, workers on how to handle rape victims. Mrs. Bernie Ryan, said that the essence of the st th The five days training which started from 1 -5 training was to impart practical knowledge and wide February 2016, was organized in Enugu for different scale experience to participants in relation to states across the federation. The objective was on the providing services to victims of sexual violence in need to set up a Sexual Assault Referral Centre and terms of physical, emotional and medical support. train participants on how to manage it as well as She extolled the participants and urged them to respond to the victims properly. The participants change their mindset and attitudes toward sexual drawn from Zamfara, Yobe, Kaduna, Enugu, Ekiti, assault victims so that more people could be helped. Cross River and Akwa Ibom states, were being A medical consultant and participant, Dr Nene trained on technical skills, forensic examination and Andem, said that the training had exposed her a lot to counseling. -

Federal Government of Nigeria 2011 Budget Federal Ministry of Land and Housing

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA 2011 BUDGET SUMMARY FEDERAL MINISTRY OF LAND AND HOUSING TOTAL PERSONNEL TOTAL OVERHEAD TOTAL TOTAL CODE MDA COST COST RECURRENT TOTAL CAPITAL ALLOCATION =N= =N= =N= =N= =N= MINISTRY OF LANDS & 0250001 HOUSING 3,137,268,528 418,458,068 3,555,726,596 33,147,994,158 36,703,720,754 TOTAL 3,137,268,528 418,458,068 3,555,726,596 33,147,994,158 36,703,720,754 27,227,159,376 15,086,283,689 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY LAND AND HOUSING: 1 2011 AMENDMENT APPROPRIATION FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA 2011 AMENDMENT APPROPRIATION CODE LINE ITEM (=N=) TOTAL: MINISTRY OF LANDS & HOUSING 36,703,720,754 TOTAL ALLOCATION: 36,703,720,754 21 PERSONNEL COST 3,137,268,528 2101 SALARY 2,789,977,780 210101 SALARIES AND WAGES 2,789,977,780 21010101 CONSOLIDATED SALARY 2,789,977,780 2102 ALLOWANCES AND SOCIAL CONTRIBUTION 347,290,748 210202 SOCIAL CONTRIBUTIONS 347,290,748 21020201 NHIS 138,916,299 21020202 CONTRIBUTORY PENSION 208,374,449 22 TOTAL GOODS AND NON - PERSONAL SERVICES - GENERAL 418,458,068 2202 OVERHEAD COST 418,458,068 220201 TRAVEL& TRANSPORT - GENERAL 138,312,778 22020101 LOCAL TRAVEL & TRANSPORT: TRAINING 29,251,947 22020102 LOCAL TRAVEL & TRANSPORT: OTHERS 58,059,000 22020103 INTERNATIONAL TRAVEL & TRANSPORT: TRAINING 24,496,875 22020104 INTERNATIONAL TRAVEL & TRANSPORT: OTHERS 26,504,956 220202 UTILITIES - GENERAL 13,136,994 22020201 ELECTRICITY CHARGES 6,237,000 22020202 TELEPHONE CHARGES 3,534,300 22020203 INTERNET ACCESS CHARGES 900,000 22020205 WATER RATES 1,945,944 22020206 SEWERAGE CHARGES 519,750 220203 MATERIALS & -

Niger Delta Budget Monitoring Group Mapping

CAPACITY BUILDING TRAINING ON COMMUNITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT & SHADOW BUDGETING NIGER DELTA BUDGET MONITORING GROUP MAPPING OF 2016 CAPITAL PROJECTS IN THE 2016 FGN BUDGET FOR ENUGU STATE (Kebetkache Training Group Work on Needs Assessment Working Document) DOCUMENT PREPARED BY NDEBUMOG HEADQUARTERS www.nigerdeltabudget.org ENUGU STATE FEDERAL MINISTRY OF EDUCATION UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION (UBE) COMMISSION S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Teaching and Learning 40,000,000 Enugu West South East New Materials in Selected Schools in Enugu West Senatorial District 2 Construction of a Block of 3 15,000,000 Udi Ezeagu/ Udi Enugu West South East New Classroom with VIP Office, Toilets and Furnishing at Community High School, Obioma, Udi LGA, Enugu State Total 55,000,000 FGGC ENUGU S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Construction of Road Network 34,264,125 Enugu- North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Enugu South 2 Construction of Storey 145,795,243 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Building of 18 Classroom, Enugu South Examination Hall, 2 No. Semi Detached Twin Buildings 3 Purchase of 1 Coastal Bus 13,000,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East Enugu South 4 Completion of an 8-Room 66,428,132 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Storey Building Girls Hostel Enugu South and Construction of a Storey Building of Prep Room and Furnishing 5 Construction of Perimeter 15,002,484 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Fencing Enugu South 6 Purchase of one Mercedes 18,656,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Water Tanker of 11,000 Litres Enugu South Capacity Total 293,145,984 FGGC LEJJA S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. -

NIGERIAN AGRICULTURAL JOURNAL ISSN: 0300-368X Volume 49 Number 2, October 2018

NIGERIAN AGRICULTURAL JOURNAL ISSN: 0300-368X Volume 49 Number 2, October 2018. Pp. 242-247 Available online at: http://www.ajol.info/index.php/naj EFFECT OF RURAL-URBAN MIGRATION ON RICE PRODUCTION IN ENUGU STATE, NIGERIA 1Apu, U., 1Okore, H.O., 2Nnamerenwa, G.C. and 1Gbede, O.A. 1Department of Rural Sociology and Extension; 2Department of Agricultural Economics, Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike, Abia State Corresponding Authors’ email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study assessed the effect of rural-urban migration on rice production in Enugu State, Nigeria. Multi-stage and Purposive sampling procedure was used to select 60 respondents which constituted the sample size of the study. Data were obtained through the use of a structured questionnaire. Descriptive statistics such as frequency counts and percentages, and inferential statistics such as correlation and z-test procedure were employed for analyses of data. Findings indicated that majority of the respondents (81.67%) were at their youthful age of 16 to 45 years old. The highest household size obtained was between 4 and 9 persons per household. Majority of the respondents in the study area (53.33%) were small scale farmers and had below 6 hectares of rice farm land. Poor living conditions, low influx of income and lack of employment were the most important reasons for rural-urban migration as confirmed by the respondents in Enugu State (65.00%). In the study area, 62.68% migrated to the urban areas. A larger proportion of the respondents (60.00%) indicated that between 4 and 9 household members participated in the rice production activities. -

ANALYSIS of the PERCEPTIONS of MOTHERS on HYGIENE FACTORS AFFECTING DIARRHEA OCCURRENCE in ENUGU STATE, NIGERIA. Nwachukwu, M. C

International Journal of Public Health, Pharmacy and Pharmacology Vol. 4, No.4, pp.25-38, November 2019 Published by ECRTD-UK Print ISSN: (Print) ISSN 2516-0400 Online ISSN: (Online) ISSN 2516-0419 ANALYSIS OF THE PERCEPTIONS OF MOTHERS ON HYGIENE FACTORS AFFECTING DIARRHEA OCCURRENCE IN ENUGU STATE, NIGERIA. Nwachukwu, M. C, Department of Environmental Management, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. [email protected]. Uchegbu, S. N, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus. [email protected] Okoye, C. O, Department of Environmental Management, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. ABSTRACT: Owing to the fact that perceptions of mothers on the hygiene factors affecting diarrhea occurrence contribute to their level of hygiene practice which may affect the incidence of diarrhea within the families, there arises the need to analyze the perception of mothers on these hygiene factors in Enugu State. The methodology adopted for the study was longitudinal survey design. Schedules were used to collect data on diarrhea among children 0-5 years from seven District Hospitals representing District Health Boards from 2007 to 2016 while questionnaire was used to collect data in respect of perceptions of mothers on hygiene factors. A total of 1110 questionnaire were administered and 1106 collected. Analysis of variance ANOVA was conducted and the study found that the perceptions of mothers on hygiene factors affecting diarrhea occurrence differ very significantly amongst the study locations (p = 0.000). Furthermore, using multiple comparison tests to detect and rank the mothers perception in the different study locations, Enugu District Health Board has the highest perception, followed by Agbani and Udi District Health Boards. -

Enugu State Nigeria Erosion and Watershed

RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) Public Disclosure Authorized ENUGU STATE NIGERIA EROSION AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (NEWMAP) Public Disclosure Authorized FOR THE 9TH MILE GULLY EROSION SUB-PROJECT INTERVENTION SITE Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) ENUGU STATE NIGERIA EROSION AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (NEWMAP) FOR THE 9TH MILE GULLY EROSION SUB-PROJECT INTERVENTION SITE FINAL REPORT Submitted to: State Project Management Unit Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project (NEWMAP) Enugu State NIGERIA NOVEMBER 2014 Page | ii Resettlement Action Plan for 9th Mile Gully Erosion Site Enugu State- Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS.................................................................................................................................................................... ii LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................................................... v LIST OF TABLES...................................................................................................................................................................... v LIST OF PLATES ...................................................................................................................................................................... v DEFINITIONS ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST