The Thirteenth Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smokejumper, Issue No. 111, January 2021

The National Smokejumper Quarterly Magazine Association January 2021 Smokejumper Me and Vietnam ................................................................................................... 4 Birth of a Tree Farmer ........................................................................................ 10 John McDaniel Retires ...................................................................................... 15 CONTENTS Message from Message from the President ....................................2 Me and Vietnam ......................................................4 the President Birth of a Tree Farmer ..........................................10 Sounding Off from the Editor ................................14 major fires in Oregon. Across John McDaniel Retires As NSA Membership the state a sum total of 1 mil- Chair..............................................................15 lion acres were burned, thou- As I Best Remember It ..........................................18 sands of structures were lost, The Jump List .......................................................20 and several rural towns were Men of the ’40s.....................................................20 leveled. After two weeks of fire Recording Smokejumper History ..........................24 and smoke, significant rainfall Four NSA Members Clear Trails In Eagle Cap Wilder- gave firefighters an opportunity ness ...............................................................29 to engage in serious contain- Odds and Ends .....................................................30 -

LOOKOUT NETWORK (ISSN 2154-4417), Is Published Quarterly by the Forest Fire Lookout Association, Inc., Keith Argow, Publisher, 374 Maple Nielsen

VOL. 26 NO. 4 WINTER 2015-2016 LLOOKOOKOUTOUT NETWNETWORKORK THE QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE FOREST FIRE LOOKOUT ASSOCIATION, INC. · 2016 Western Conference - June 10-12, John Day, Oregon · FFLA Loses Founding Member - Henry Isenberg · Northeast Conference - September 17-18, New York www.firelookout.org ON THE LOOKOUT From the National Chairman Keith A. Argow Vienna, Virginia Winter 2015-2016 FIRE TOWERS IN THE HEART OF DIXIE On Saturday, January 16 we convened the 26th annual member of the Alabama Forestry Commission who had meeting of the Forest Fire Lookout Association at the Talladega purchased and moved a fire tower to his woodlands; the project Ranger Station, on the Talladega National Forest in Talladega, leader of the Smith Mountain fire tower restoration; the publisher Alabama (guess that is somewhere near Talladega!). Our host, of a travel magazine that promoted the restoration; a retired District Ranger Gloria Nielsen, and Alabama National Forests district forester with the Alabama Forestry Commission; a U.S. Assistant Archaeologist Marcus Ridley presented a fine Forest Service District Ranger (our host), and a zone program including a review of the multi-year Horn Mountain archaeologist for the Forest Service. Add just two more Lookout restoration. A request by the radio communications members and we will have the makings of a potentially very people to construct a new effective chapter in Alabama. communications tower next to The rest of afternoon was spent with an inspection of the the lookout occasioned a continuing Horn Mountain Lookout restoration project, plus visits review on its impact on the 100-foot Horn Mountain Fire Tower, an historic landmark visible for many miles. -

Escape Fire: Lessons for the Future of Health Care

Berwick Escape Fire lessons for the future oflessons for the future care health lessons for the future of health care Donald M. Berwick, md, mpp president and ceo institute for healthcare improvement ISBN 1-884533-00-0 the commonwealth fund Escape Fire lessons for the future of health care Donald M. Berwick, md, mpp president and ceo institute for healthcare improvement the commonwealth fund new york, new york The site of the Mann Gulch fire, which is described in this book, is listed introduction in the National Register of Historic Places. Because many regard it as sacred ground, it is actively protected and managed by the Forest Service as a cultural landscape. On December 9, 1999, the nearly 3,000 individuals who attended the 11th Annual National Forum on Quality Improvement in Health Care heard an extraordinary address by Dr. Donald M. Berwick, the founder, president, and CEO of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the forum’s sponsor. Entitled Escape Fire, Dr. Berwick’s speech took its audience back to the year 1949, when a wildfire broke out on a Montana hillside, taking the lives of 13 young men and changing the way firefighting was managed in the United States. After retelling this harrowing tale, Dr. Berwick applied the Escape Fire is an edited version of the Plenary Address delivered at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s 11th Annual National Forum lessons learned from this catastrophe to the health care on Quality Improvement in Health Care, in New Orleans, Louisiana, on December 9, 1999. system—a system that, he believes, is on the verge of its Copyright © 2002 Donald M. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NFS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-O01B (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number ——— Page ——— SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 99000596 Date Listed: 5/19/99 Mann Gulch Wildfire Historic District Lewis & Clark MT Property Name County State N/A Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. Signature/of /-he Keeper Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: U. T. M. Coordinates: U. T. M. coordinates 1 and 2 are revised to read: 1) 12 431300 5190880 2) 12 433020 5193740 This information was confirmed with C. Davis of the Helena National Forest, MT. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NPS Form 10-900 No. 1024 0018 (Rev. Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2/ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service 20BP9 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLA :ESJ REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Mann Gulch Wildfire Historic District other name/site number: 24LC1160 2. Location street & number: Mann Gulch, a tributary of the Missouri River, Helena National Forest not for publication: na vicinity: X city/town: Helena state: Montana code: Ml county: Lewis and Clark code: 049 zip code: 59601 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibilityj^eejsjhe documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professj^rafrequirernente set Jfortjjin 36 CFR Part 60. -

A History of the Arôhitecture Of

United States Department of Agriculture A History of the I Forest Service Engineering Staff EM-731 0-8 Arôhitecture of the July 1999 USDA Forest Service a EM-731 0-8 C United States Department of Agriculture A History of the Forest Service EngIneering Staff EM-731 0-8 Architecture of the July 1999 USDA Forest Service by John A. Grosvenor, Architect Pacific Southwest Region Dedication and Acknowledgements This book is dedicated to all of those architects andbuilding designers who have provided the leadership and design expertise tothe USDA Forest Service building program from the inception of theagencyto Harry Kevich, my mentor and friend whoguided my career in the Forest Service, and especially to W. Ellis Groben, who provided the onlyprofessional architec- tural leadership from Washington. DC. I salute thearchaeologists, histori- ans, and historic preservation teamswho are active in preserving the architectural heritage of this unique organization. A special tribute goes to my wife, Caro, whohas supported all of my activi- ties these past 38 years in our marriage and in my careerwith the Forest Service. In the time it has taken me to compile this document, scoresof people throughout the Forest Service have provided information,photos, and drawings; told their stories; assisted In editing my writingattempts; and expressed support for this enormous effort. Active andretired architects from all the Forest Service Regions as well as severalof the research sta- tions have provided specific informationregarding their history. These individuals are too numerous to mention by namehere, but can be found throughout the document. I do want to mention the personwho is most responsible for my undertaking this task: Linda Lux,the Regional Historian in Region 5, who urged me to put somethingdown in writing before I retired. -

Fire Lookouts Eldorado National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Fire Lookouts Eldorado National Forest Background Fire suppression became a national priority around 1910, when the country was stricken by what has been considered the largest wildfire in US history. The Big Blowup fire as it was called, burned over 3,000,000 acres (12,000 km) in Washington, Idaho, and Montana. After the Big Blowup, Fire Lookout towers were built across the country in hopes of preventing another “Blowup”. At this time Plummer Lookout. Can lookouts were primarily found in tall trees with rickety ladders and you see the 2 people? platforms or on high peaks with canvas tents for shelters. This job was not for the faint of heart. This did little to offer long‐term support for the much needed “Fire Watcher”, so by 1911 permanent cabins and cupolas were constructed on Mountain Ridges, Peaks, and tops. In California, between 1933 and 1942, Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) crews reportedly built 250 fire lookout towers. These crews also helped build access roads for the construction of these towers. Fire lookouts were at peak use from the 1930s through the 1950s. During World War II fire lookouts were assigned additional duties as Enemy Aircraft Spotters protecting the countries coastal lines and beaches. By the 1960s the Fire Lookouts were being used less frequently due to the rise in technology. Many lookouts were closed, or turned in to recreational facilities. Big Hill On the Eldorado ... Maintained and staffed 7 days a week The Eldorado Naonal Forest originally had 9 lookouts at the during fire season the Big Hill Lookout is beginning of the century. -

1933–1941, a New Deal for Forest Service Research in California

The Search for Forest Facts: A History of the Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, 1926–2000 Chapter 4: 1933–1941, A New Deal for Forest Service Research in California By the time President Franklin Delano Roosevelt won his landslide election in 1932, forest research in the United States had grown considerably from the early work of botanical explorers such as Andre Michaux and his classic Flora Boreali- Americana (Michaux 1803), which first revealed the Nation’s wealth and diversity of forest resources in 1803. Exploitation and rapid destruction of forest resources had led to the establishment of a federal Division of Forestry in 1876, and as the number of scientists professionally trained to manage and administer forest land grew in America, it became apparent that our knowledge of forestry was not entirely adequate. So, within 3 years after the reorganization of the Bureau of Forestry into the Forest Service in 1905, a series of experiment stations was estab- lished throughout the country. In 1915, a need for a continuing policy in forest research was recognized by the formation of the Branch of Research (BR) in the Forest Service—an action that paved the way for unified, nationwide attacks on the obvious and the obscure problems of American forestry. This idea developed into A National Program of Forest Research (Clapp 1926) that finally culminated in the McSweeney-McNary Forest Research Act (McSweeney-McNary Act) of 1928, which authorized a series of regional forest experiment stations and the undertaking of research in each of the major fields of forestry. Then on March 4, 1933, President Roosevelt was inaugurated, and during the “first hundred days” of Roosevelt’s administration, Congress passed his New Deal plan, putting the country on a better economic footing during a desperate time in the Nation’s history. -

Umatilla NF Recruitment Info Brochure.Indd

Seasonal Positions Available The Umatilla National Forest is seeking motivated individuals to fill natural resource and firefighting United States Department of Agriculture positions. These are federal positions that require hard work and dedication. A passion for the outdoors is required. RECRUITMENT INFORMATION Start Your Career Many career Forest Service employees started out as We will being accepting seasonal employees, this is how they “got their foot in applications from the door”. November 14 to Many firefighting jobs look for wildland fire experience November 20! and training. Each seasonal employee will have an opportunity to attend an on-the-job firefighter training. Setup your profile now on This training, called “Guard School”, is a one week school USAjobs.gov! covering the basics of wildland fire suppression, fire behavior, human factors, and the incident command system (S-130, S-190, S-110, I-100, L-180). Upon completion of “Guard School” the employee will be qualified to fight wildland fire as a Fire Fighter Type 2. Applying through USAJOBS Contact Informati on All applications must be submitted through usajobs.gov. htt ps://www.fs.usda.gov/main As with any online job site, the application process /umati lla/about-forest/jobs requires information about you that may not be readily www.facebook.com/Umati llaNF/ available. We recommend gathering information, creating a profile, and giving yourself ample time to Umati lla Nati onal Forest complete the application process. Applications must be Supervisor’s Offi ce 72510 Coyote Road submitted by the time indicated on the closing date. We Pendleton, OR 97801 are unable to accept late applications. -

Chapter 12 Review

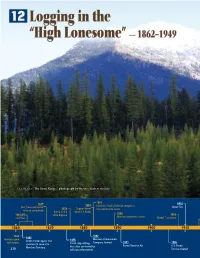

FIGURE 12.1: “The Swan Range,” photograph by Donnie Sexton, no date 1883 1910 1869 1883 First transcontinental Northern Pacifi c Railroad completes Great Fire 1876 Copper boom transcontinental route railroad completed begins in Butte Battle of the 1889 1861–65 Little Bighorn 1908 Civil War Montana becomes a state Model T invented 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1862 1882 1862 Montana gold Montana Improvement Anton Holter opens fi rst 1875 rush begins Salish stop setting Company formed 1891 1905 commercial sawmill in Forest Reserve Act U.S. Forest Montana Territory fi res after confrontation 230 with law enforcement Service created READ TO FIND OUT: n How American Indians traditionally used fire n Who controlled Montana’s timber industry n What it was like to work as a lumberjack n When and why fire policy changed The Big Picture For thousands of years people have used forests to fill many different needs. Montana’s forestlands support our economy, our communities, our homes, and our lives. Forests have always been important to life in Montana. Have you ever sat under a tall pine tree, looked up at its branches sweeping the sky, and wondered what was happen- ing when that tree first sprouted? Some trees in Montana are 300 or 400 years old—the oldest living creatures in the state. They rooted before horses came to the Plains. Think of all that has happened within their life spans. Trees and forests are a big part of life in Montana. They support our economy, employ our people, build our homes, protect our rivers, provide habitat for wildlife, influence poli- tics, and give us beautiful places to play and be quiet. -

MONTANA 2018 Vacation & Relocation Guide

HelenaMONTANA 2018 Vacation & Relocation Guide We≥ve got A Publication of the Helena Area Chamber of Commerce and The Convention & Visitors Bureau this! We will search for your new home, while you spend more time at the lake. There’s a level of knowledge our Helena real estate agents offer that goes beyond what’s on the paper – it’s this insight that leaves you confident in your decision to buy or sell. Visit us at bhhsmt.com Look for our new downtown office at: 50 S Park Avenue Helena, MT 59601 406.437.9493 A member of the franchise system BHH Affiliates, LLC. Equal Housing Opportunity. An Assisted Living & Memory Care community providing a Expect more! continuum of care for our friends, family & neighbors. NOW OPEN! 406.502.1001 3207 Colonial Dr, Helena | edgewoodseniorliving.com 2005, 2007, & 2016 People’s Choice Award Winner Sysum HELENA I 406-495-1195 I SYSUMHOME.COM Construction 2018 HELENA GUIDE Contents Landmark & Attractions and Sports & Recreation Map 6 Welcome to Helena, Attractions 8 Fun & Excitement 14 Montana’s capital city. Arts & Entertainment 18 The 2018 Official Guide to Helena brings you the best ideas for enjoying the Queen City - from Shopping 22 exploring and playing to living and working. Dining Guide 24 Sports & Recreation 28 We≥ve got Day Trips 34 A Great Place to Live 38 this! A Great Place to Retire 44 Where to Stay 46 ADVERTISING Kelly Hanson EDITORIAL Cathy Burwell Mike Mergenthaler Alana Cunningham PHOTOS Convention & Visitors Bureau Montana Office of Tourism Cover Photo: Mark LaRowe MAGAZINE DESIGN Allegra Marketing 4 Welcome to the beautiful city of Helena! It is my honor and great privilege to welcome you to the capital city of Montana. -

Spatial Patterns and Physical Factors of Smokejumper Utilization Since 2004

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2014 SPATIAL PATTERNS AND PHYSICAL FACTORS OF SMOKEJUMPER UTILIZATION SINCE 2004 Tyson A. Atkinson University of Montana - Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Forest Management Commons, and the Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Atkinson, Tyson A., "SPATIAL PATTERNS AND PHYSICAL FACTORS OF SMOKEJUMPER UTILIZATION SINCE 2004" (2014). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4384. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4384 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPATIAL PATTERNS AND PHYSICAL FACTORS OF SMOKEJUMPER UTILIZATION SINCE 2004 By TYSON ALLEN ATKINSON Bachelor of Science, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, 2009 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Forestry The University of Montana Missoula, MT December 2014 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr. Carl A. Seielstad, Chair Department of Forest Management Dr. LLoyd P. Queen Department of Forest Management Dr. Charles G. Palmer Department of Health and Human Performance Atkinson, Tyson Allen, M.S., December 2014 Forestry Spatial Patterns and Physical Factors of Smokejumper Utilization since 2004 Chairperson: Dr. Carl Seielstad Abstract: This research examines patterns of aerial smokejumper usage in the United States. -

ISMOG Interagency Smokejumper Operations Guide, Forest Service

l In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C.