Ivan the Terrible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History 251 Medieval Russia

Medieval Russia Christian Raffensperger History 251H/C - 1W Fall Semester - 2012 MWF 11:30-12:30 Hollenbeck 318 Russia occupies a unique position between Europe and Asia. This class will explore the creation of the Russian state, and the foundation of the question of is Russia European or Asian? We will begin with the exploration and settlement of the Vikings in Eastern Europe, which began the genesis of the state known as “Rus’.” That state was integrated into the larger medieval world through a variety of means, from Christianization, to dynastic marriage, and economic ties. However, over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the creation of the crusading ideal and the arrival of the Mongols began the process of separating Rus’ (becoming Russia) from the rest of Europe. This continued with the creation of power centers in NE Russia, and the transition of the idea of empire from Byzantium at its fall to Muscovy. This story of medieval Russia is a unique one that impacts both the traditional history of medieval Europe, as well as the birth of the first Eurasian empire. Professor: Christian Raffensperger Office: Hollenbeck 311 Office Phone: 937-327-7843 Office Hours: MWF 9:00–11:00 A.M. or by appointment E-mail address: [email protected] Assignments and Deadlines The format for this class is lecture and discussion, and thus attendance is a main requirement of the course, as is participation. As a way to track your progress on the readings, there will be a series of quizzes during class. All quizzes will be unannounced. -

The Russian Five Austin M

Masthead Logo Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2019 yS mposium Apr 3rd, 1:30 PM - 2:00 PM The Russian Five Austin M. Doub Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Art Practice Commons, Audio Arts and Acoustics Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Doub, Austin M., "The Russian Five" (2019). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 7. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2019/podium_presentations/7 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by Footer Logo DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Austin Doub December 11, 2018 Senior Seminar Dr. Yang Abstract: This paper will explore Russian culture beginning in the mid nineteenth-century as the leading group of composers and musicians known as the Moguchaya Kuchka, or The Russian Five, sought to influence Russian culture and develop a pure school of Russian music. Comprised of César Cui, Aleksandr Borodin, Mily Balakirev, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolay Rimksy-Korsakov, this group of inspired musicians, steeped in Russian society, worked to remove outside cultural influences and create a uniquely Russian sound in their compositions. As their nation became saturated with French and German cultures and other outside musical influences, these musicians composed with the intent of eradicating ideologies outside of Russia. In particular, German music, under the influence of Richard Wagner, Robert Schumann, and Johannes Brahms, reflected the pan-Western-European style and revolutionized the genre of opera. -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

Russian Arts on the Rise

Arts and Humanities Open Access Journal Proceeding Open Access Russian arts on the rise Proceeding Volume 2 Issue 1 - 2018 The fifth Graduate Workshop of the Russian Art and Culture Miriam Leimer Group (RACG) once again proofed how vivid the art and culture of Free University of Berlin, Germany Russia and its neighbours are discussed among young researchers. th Though still little represented in the curricula of German universities Correspondence: Miriam Leimer, 5 Graduate Workshop of the Russian Art and Culture Group (RACG), Free University of the art of Eastern Europe is the topic of many PhD theses. But also in Berlin, Germany, Email [email protected] a broader international context-both in the East and the West-Russian art has gained importance in the discipline of art history. Received: December 22, 2017 | Published: February 02, 2018 The Russian Art and Culture Group that was founded in 2014 by Isabel Wünsche at Jacobs University Bremen provides an international platform for scholars and younger researchers in this The second panel “Intergenerational Tensions and Commonalities” field. At least once a year members of the group organize a workshop focused on the relation between the representatives of the different to bring together recent research-mostly by PhD candidates as well as succeeding art movements at the turn of the century. Using the by already well-established academics. example of Martiros Saryan, an Armenian artist, Mane Mkrtchyan from the Institute of Arts at the National Academy of Sciences of For the first time the workshop did not take place in Bremen the Republic of Armenia shed light on Russia’s Symbolism. -

International Scholarly Conference the PEREDVIZHNIKI ASSOCIATION of ART EXHIBITIONS. on the 150TH ANNIVERSARY of the FOUNDATION

International scholarly conference THE PEREDVIZHNIKI ASSOCIATION OF ART EXHIBITIONS. ON THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FOUNDATION ABSTRACTS 19th May, Wednesday, morning session Tatyana YUDENKOVA State Tretyakov Gallery; Research Institute of Theory and History of Fine Arts of the Russian Academy of Arts, Moscow Peredvizhniki: Between Creative Freedom and Commercial Benefit The fate of Russian art in the second half of the 19th century was inevitably associated with an outstanding artistic phenomenon that went down in the history of Russian culture under the name of Peredvizhniki movement. As the movement took shape and matured, the Peredvizhniki became undisputed leaders in the development of art. They quickly gained the public’s affection and took an important place in Russia’s cultural life. Russian art is deeply indebted to the Peredvizhniki for discovering new themes and subjects, developing critical genre painting, and for their achievements in psychological portrait painting. The Peredvizhniki changed people’s attitude to Russian national landscape, and made them take a fresh look at the course of Russian history. Their critical insight in contemporary events acquired a completely new quality. Touching on painful and challenging top-of-the agenda issues, they did not forget about eternal values, guessing the existential meaning behind everyday details, and seeing archetypal importance in current-day matters. Their best paintings made up the national art school and in many ways contributed to shaping the national identity. The Peredvizhniki -

Jan Sobczak Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich of Russia

Jan Sobczak Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich of Russia Echa Przeszłości 12, 143-156 2011 ECHA PRZESZŁOŚCI XII, 2011 ISSN 1509-9873 Jan Sobczak ALEXEI NIKOLAEVICH, TSAREVICH OF RUSSIA This article does not aspire to give an exhaustive account of the life of Alexei Nikolaevich, not only for reasons of limited space. The role played by the young lad who was much loved by the nation, became the Russian tsesarevich and was murdered at the tender age of 14, would not justify such an effort. In addition to delivering general biographical information about Alexei that can be found in a variety of sources, I will attempt to throw some light on the less known aspects of his life that profoundly affected the fate of the Russian Empire and brought tragic consequences for the young imperial heir1. Alexei Nikolaevich was born in Peterhof on 12 August (30 July) 1904 on Friday at noon, during an unusually hot summer that had started already in February, at the beginning of Russia’s much unfortunate war against Japan. Alexei was the fifth child and the only son of Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna. He had four older sisters who were the Grand Duchesses: Olga (8.5 years older than Alexei), Tatiana (7 years older), Maria (5 years older) and Anastasia (3 years older). In line with the law of succession, Alexei automatically became heir to the throne, and his birth was heralded to the public by a 300-gun salute from the Peter and Paul Fortress. According to Nicholas II, the imperial heir was named Alexei to break away from a nearly century-old tradition of naming the oldest sons Alexander and Nicholas and to commemorate Peter the Great’s father, Alexei Mikhailovich, the second tsar of the Romanov dynasty that had ruled over Russia for nearly 300 years from the 17th century. -

The End of Boris. Contribution to an Aesthetics of Disorientation

The end of Boris. ConTriBuTion To an aesTheTiCs of disorienTaTion by reuven Tsur The Emergence of the Opera–An Outline Boris Godunov was tsar of russia in the years 1598–1605. he came to power after fyodor, the son of ivan the terrible, died without heirs. Boris was fyodor's brother-in-law, and in fact, even during fyodor's life he was the omnipotent ruler of russia. ivan the Terrible had had his eldest son executed, whereas his youngest son, dmitri, had been murdered in unclear circumstances. in the 16–17th centuries, as well as among the 19th-century authors the prevalent view was that it was Boris who ordered dmitri's murder (some present-day historians believe that dmitri's murder too was ordered by ivan the Terrible). in time, two pretenders appeared, one after the other, who claimed the throne, purporting to be dmitri, saved miraculously. Boris' story got told in many versions, in history books and on the stage. Most recently, on 12 July 2005 The New York Times reported the 295-year-late premiere of the opera Boris Goudenow, or The Throne Attained Through Cunning, or Honor Joined Happily With Affection by the German Baroque composer Johann Mattheson. Boris' story prevailed in three genres: history, tragedy, and opera. in the nineteenth century, the three genres culminated in n. M. Karamzin's monumental History of the Russian State, in alexander Pushkin's tragedy Boris Godunov, and in Modest Mussorgsky's opera Boris Godunov. each later author in this list liberally drew upon his predecessors. in her erudite and brilliant 397 reuven tsur the end of boris book, Caryl emerson (1986) compared these three versions in a Pimen interprets as an expression of the latter's ambition. -

Background Guide, and to Issac and Stasya for Being Great Friends During Our Weird Chicago Summer

Russian Duma 1917 (DUMA) MUNUC 33 ONLINE 1 Russian Duma 1917 (DUMA) | MUNUC 33 Online TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________ CHAIR LETTERS………………………….….………………………….……..….3 ROOM MECHANICS…………………………………………………………… 6 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM………………………….……………..…………......9 HISTORY OF THE PROBLEM………………………………………………………….16 ROSTER……………………………………………………….………………………..23 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………..…………….. 46 2 Russian Duma 1917 (DUMA) | MUNUC 33 Online CHAIR LETTERS ____________________________________________________ My Fellow Russians, We stand today on the edge of a great crisis. Our nation has never been more divided, more war- stricken, more fearful of the future. Yet, the promise and the greatness of Russia remains undaunted. The Russian Provisional Government can and will overcome these challenges and lead our Motherland into the dawn of a new day. Out of character. To introduce myself, I’m a fourth-year Economics and History double major, currently writing a BA thesis on World War II rationing in the United States. I compete on UChicago’s travel team and I additionally am a CD for our college conference. Besides that, I am the VP of the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, previously a member of an all-men a cappella group and a proud procrastinator. This letter, for example, is about a month late. We decided to run this committee for a multitude of reasons, but I personally think that Russian in 1917 represents such a critical point in history. In an unlikely way, the most autocratic regime on Earth became replaced with a socialist state. The story of this dramatic shift in government and ideology represents, to me, one of the most interesting parts of history: that sometimes facts can be stranger than fiction. -

The Tsars' CABINET

The Tsars’ Cabinet: Two Hundred Years of Russian Decorative Arts under the Romanovs The Tsars’ Cabinet: Two Hundred Years of Russian Decorative Arts under the Romanovs Education Packet Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………..2 Glossary……………………………………………...........5 Services…………………………………………………….7 The Romanov Dynasty.……………………………..............9 Meet the Romanovs……….……………………………….10 Speakers List...…………………………………..………...14 Bibliography……………………………………………….15 Videography……………………………………………….19 Children’s Activity…………………………………………20 The Tsars’ Cabinet: Two Hundred Years of Russian Decorative Arts under the Romanovs is developed from the Kathleen Durdin Collection and is organized by the Muscarelle Museum of Art at the College of William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, in collaboration with International Arts & Artists, Washington, DC. The Tsars’ Cabinet This exhibition illustrates more than two hundred years of Russian decorative arts: from the time of Peter the Great in the early eighteenth century to that of Nicolas II in the early twentieth century. Porcelain, glass, enamel, silver gilt and other alluring materials make this extensive exhibition dazzle and the objects exhibited provide a rare, intimate glimpse into the everyday lives of the tsars. The collection brings together a political and social timeline tied to an understanding of Russian culture. The Tsars’ Cabinet will transport you to a majestic era of progressive politics and dynamic social change. The Introduction of Porcelain to Russia During the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, Europe had a passion for porcelain. It was not until 1709 that Johann Friedrich Böttger, sponsored by Augustus II (known as Augustus the Strong) was able to reproduce porcelain at Meissen, Germany. After Augustus II began manufacturing porcelain at the Meissen factory, other European monarchs attempted to establish their own porcelain factories. -

“Zhili-Byli…”: Russian Folklore in the Intermediate Language Classroom

“Zhili-byli…”: Russian Folklore in the Intermediate Language Classroom BLC Project, Fall 2019 Kit Pribble (GSR, Slavic Dept.) Textual features of the fairytale ◦ Formulaic, often cyclical narrative structure ◦ Combination of vivid imagery + concrete plot ◦ Repetition and the rule of 3 ◦ Orality (alliteration, rhyme, & mnemonic devices) Project Goals 1) To gradually build students’ comfort level with reading narrative texts in Russian 2) To introduce students to a foundational aspect of Russian culture, while also engaging students in a critical consideration of how national cultures are conceived or constructed Focus: Traditional Magic Tales and their 20th Century Adaptations 1) Recorded textual variants • Alexander Afanasyev’s collection of Russian fairytales, 1860s 2) 20th century revisions and adaptations • Ballets (Modernist and Soviet) • Modernist paintings and illustrations • Soviet rock music • Animated films (Soviet and Post-Soviet) • Advertisements • Political emblems and political cartoons Project Goals 1) To gradually build students’ comfort level with reading narrative texts in Russian 2) To introduce students to a foundational aspect of Russian culture, while also engaging students in a critical consideration of how national cultures are conceived or constructed Cluster 1: The 3 Bogatyrs Learning goals: 1) Introduce students to the genre of the bylina (East Slavic heroic epic), as well as later re-castings of the bogatyrs (Slavic epic heroes) in Modernist and Post-Soviet art 2) Increase students’ sensitivity to register and -

Russian Viking and Royal Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY RUSSIAN/VIKING ANCESTRY Direct Lineage from: Rurik Ruler of Kievan Rus to: Lars Erik Granholm 1 Rurik Ruler of Kievan Rus b. 830 d. 879 m. Efenda (Edvina) Novgorod m. ABT 876 b. ABT 850 2 Igor Grand Prince of Kiev b. ABT 835 Kiev,Ukraine,Russia d. 945 Kiev,Ukraine,Russia m. Olga Prekrasa of Kiev b. ABT 890 d. 11 Jul 969 Kiev 3 Sviatoslav I Grand Prince of Kiev b. ABT 942 d. MAR 972 m. Malusha of Lybeck b. ABT 944 4 Vladimir I the Great Grand Prince of Kiev b. 960 Kiev, Ukraine d. 15 Jul 1015 Berestovo, Kiev m. Rogneda Princess of Polotsk b. 962 Polotsk, Byelorussia d. 1002 [daughter of Ragnvald Olafsson Count of Polatsk] m. Kunosdotter Countess of Oehningen [Child of Vladimir I the Great Grand Prince of Kiev and Rogneda Princess of Polotsk] 5 Yaroslav I the Wise Grand Duke of Kiew b. 978 Kiev d. 20 Feb 1054 Kiev m. Ingegerd Olofsdotter Princess of Sweden m. 1019 Russia b. 1001 Sigtuna, Sweden d. 10 Feb 1050 [daughter of Olof Skötkonung King of Sweden and Estrid (Ingerid) Princess of Sweden] 6 Vsevolod I Yaroslavich Grand Prince of Kiev b. 1030 d. 13 Apr 1093 m. Irene Maria Princess of Byzantium b. ABT 1032 Konstantinopel, Turkey d. NOV 1067 [daughter of Constantine IX Emperor of Byzantium and Sclerina Empress of Byzantium] 7 Vladimir II "Monomach" Grand Duke of Kiev b. 1053 d. 19 May 1125 m. Gytha Haraldsdotter Princess of England m. 1074 b. ABT 1053 d. 1 May 1107 [daughter of Harold II Godwinson King of England and Ealdgyth Swan-neck] m. -

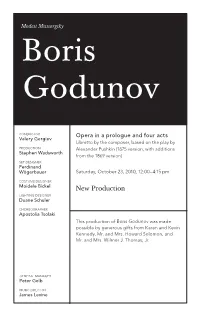

Boris Godunov

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide.