Conceptualizing the Spectrum of the Bereavement Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRAQ Reckoning Template.Qxd 04/08/2016 12:35 Page 63

IRAQ Reckoning_Template.qxd 04/08/2016 12:35 Page 63 IRAQ – The Reckoning ‘the fatuous irony of millions of liberalminded people taking to the streets, effectively to defend the most illiberal regime on earth’ Blair to Bush, 26 March 2003 IRAQ Reckoning_Template.qxd 04/08/2016 14:33 Page 64 64 Star Wars starts wars The voluminous and longoverdue report of the Iraq Inquiry, prepared by Sir John Chilcot, was finally published in July 2016. Pressure from families of service personnel killed in Iraq eventually hastened the protracted process, which commenced in 2009, six years after the invasion of Iraq led by the United States with prominent UK support. The illegal war on Iraq was always about much more than the prime actors, but Tony Blair’s impatience to oust Saddam and wilful ignorance about the absence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq leap from his correspondence with President Bush, compiled from the Chilcot Report and reprinted here. Charged with ‘learning the lessons’ of the misadventure in Iraq, the UK has gone to war in Libya and Syria while the report of the Iraq Inquiry was under preparation. Notable and informed critics of the war, such as Dr Brian Jones, formerly of Defence Intelligence Staff, have died before having a chance to see whether all their efforts to expose the fixing of intelligence in the UK proved worth while. Reg Keys, whose son, Tom, age 20 years, was one of six Military Police killed in southern Iraq in June 2003, has consistently campaigned for justice for those who died in this unnecessary war. -

People, Places and Policy

People, Places and Policy Set within the context of UK devolution and constitutional change, People, Places and Policy offers important and interesting insights into ‘place-making’ and ‘locality-making’ in contemporary Wales. Combining policy research with policy-maker and stakeholder interviews at various spatial scales (local, regional, national), it examines the historical processes and working practices that have produced the complex political geography of Wales. This book looks at the economic, social and political geographies of Wales, which in the context of devolution and public service governance are hotly debated. It offers a novel ‘new localities’ theoretical framework for capturing the dynamics of locality-making, to go beyond the obsession with boundaries and coterminous geog- raphies expressed by policy-makers and politicians. Three localities – Heads of the Valleys (north of Cardiff), central and west coast regions (Ceredigion, Pembrokeshire and the former district of Montgomeryshire in Powys) and the A55 corridor (from Wrexham to Holyhead) – are discussed in detail to illustrate this and also reveal the geographical tensions of devolution in contemporary Wales. This book is an original statement on the making of contemporary Wales from the Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research, Data and Methods (WISERD) researchers. It deploys a novel ‘new localities’ theoretical framework and innovative mapping techniques to represent spatial patterns in data. This allows the timely uncovering of both unbounded and fuzzy relational policy geographies, and the more bounded administrative concerns, which come together to produce and reproduce over time Wales’ regional geography. The Open Access version of this book, available at www.tandfebooks.com, has been made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 3.0 license. -

Iraq Rage Drives Family Furies That Will Harry Blair at the Ballot Box | the Times

14/05/2015 Iraq rage drives family furies that will harry Blair at the ballot box | The Times Share via Iraq rage drives family furies that will harry Blair at the ballot box By Burhan Wazir Published at 12:00AM, April 26 2005 In key constituencies across the country the casualties of war are making sure that they are heard THIS is about rage. Incandescent anger. The kind of fingercurling, jawtightening fury that happens to everyone at least once in their lifetime. As Rose Gentle put it: “You get so angry that you can’t see straight. You get so angry that nothing else matters. The rage stops you from grieving for your dead son.” The election, once pungent with the odour of familiarity has, in a number of constituencies, turned into a boxing match with a host of alternative and independent candidates launching a jeremiad against key ministerial constituencies. In seats such as East Kilbride, Strathaven & Lesmahagow Birmingham Hodge Hill and Sedgefield, Labour Party workers, fearful of being shouted at, keep a low profile from antiwar candidates. “Tony Blair lied, my son died,” shouted Rose Gentle, 40, campaigning in East Kilbride, a blighted new town outside Glasgow, seemingly cursed by cold weather, where she is challenging Adam Ingram, the Armed Forces Minister. As wind and rain whistled through wide avenues, Mrs Gentle, whose son Gordon, 19, died in Iraq last summer while serving with the Royal Highland Fusiliers, dropped leaflets doortodoor accompanied by supporters. “I just take it day by day,” she said, rubbing her hands together. -

View Into Invest NI, and in the Context of the — Have Benefited Greatly from the Acumen Programme

NORTHERN IRELAND tackling the challenges of economic recovery and pandemic flu. We will continue to work together in ASSEMBLY decision-making regarding contingency planning. The discussion on the economy re-emphasised the need for continued co-operation and the sharing of Tuesday 29 September 2009 economic information. It was agreed that co-operation between Her Majesty’s Government and the devolved The Assembly met at 10.30 am (Mr Deputy Speaker Administrations in tackling the recession and preparing [Mr McClarty] in the Chair). for the economic recovery through the JMC and the economic summits in Wales and Scotland had worked Members observed two minutes’ silence. well and would continue. A number of issues relating to finance were raised, including further public sector capital acceleration; MINISTERIAL STATEMENTS difficulties over bank lending, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises; and funding to deal Joint Ministerial Committee with swine flu. Those will be discussed further over the coming weeks and at the next meeting of the Plenary Meeting Finance Ministers’ quadrilateral, which is scheduled to take place in December 2009. Mr Deputy Speaker: I would like to inform Members that I have received notice from the Office of In the discussion on the state of relations, the the First Minister and deputy First Minister that the positive developments since the last plenary session, First Minister wishes to make a statement regarding particularly in the development of a new subcommittee, JMC(D), to deal with domestic matters, was noted. the Joint Ministerial Committee plenary meeting. The subcommittee has held two successful meetings to The First Minister (Mr P Robinson): I wish to date and plans to meet again in the coming months. -

LAWLESS WORLD: INTERNATIONAL LAW AFTER SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 and IRAQ* International Law After September 11, 2001 and Iraq PHILIPPE SANDS QC†

FEATURE LAWLESS WORLD: INTERNATIONAL LAW AFTER SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 AND IRAQ* International Law after September 11, 2001 and Iraq PHILIPPE SANDS QC† CONTENTS I Introduction II The Development of International Law — The Beginnings of a Rules-Based System III The Adequacy of the Existing Rules IV Australia and Britain — Following the Tough Guys A Riding Pillion on the Road to War B A Change of Mind C The Shock of the New V The Things that Matter I INTRODUCTION Until recently, the subject of international law remained in the margins. It would not have been an area which would have detained many lawyers who trained at this Law School, at least in their day-to-day practice. When I was invited to give this year’s Melbourne Law School Alumni lecture, late in 2004, issues of international law were already much in the air, certainly in Britain, and also in Australia. The Convention relating to the Status of Refugees,1 the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change2 and the legality of the war in Iraq are issues that were receiving considerable attention. But I doubt that anyone could have imagined that the run-up to Britain’s May 2005 General Election would be defined by arcane issues of international law: did the authorisation to use force against Iraq under Security Council Resolution 6783 of 1991 revive in March 2003? Was the British Prime Minister entitled to determine that Iraq was in material breach of its * This article is based on the Law School Alumni Lecture, delivered at the University of Melbourne Law School on 15 June 2005, and on the Mischon Lecture given in London on 12 May 2005. -

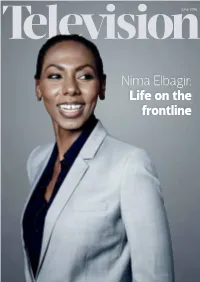

Nima Elbagir: Life on the Frontline Size Matters a Provocative Look at Short-Form Content

June 2016 Nima Elbagir: Life on the frontline Size matters A provocative look at short-form content Pat Younge CEO, Sugar Films (Chair) Randel Bryan Director of Content and Strategy UK, Endemol Shine Beyond UK Adam Gee Commissioning Editor, Multi-platform and Online Video (Factual), Channel 4 Max Gogarty Daily Content Editor, BBC Three Kelly Sweeney Director of Production/Studios, Maker Studios International Andy Taylor CEO, Little Dot Studios Steve Wheen CEO, The Distillery 4 July The Hospital Club, 24 Endell Street, London WC2H 9HQ Booking: www.rts.org.uk Journal of The Royal Television Society June 2016 l Volume 53/6 From the CEO The third annual RTS/ surroundings of the Oran Mor audito- Mockridge, CEO of Virgin Media; Cathy IET Joint Public Lec- rium in Glasgow. Congratulations to Newman, Presenter of Channel 4 News; ture, held in the all the winners. and Sharon White, CEO of Ofcom. unmatched surround- Back in London, RTS Futures held Steve Burke, CEO of NBCUniversal, ings of London’s Brit- an intimate workshop in the board- will deliver the opening keynote. ish Museum, was a room here at Dorset Rise: 14 industry An early-bird rate is available for night to remember. I newbies were treated to tips on how those of you who book a place before was thrilled to see such a big turnout. to secure work in the TV sector. June 30 – just go to the RTS website: Nobel laureate Sir Paul Nurse gave a Bookings are now open for the RTS’s rts.org.uk/event/rts-london-conference-2016. -

United Kingdom Election 2005 the 2005 United Kingdom Election Was Held on 5 May

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library RESEARCH NOTE Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament 30 May 2005, no. 51, 2004–05, ISSN 1449-8456 United Kingdom election 2005 The 2005 United Kingdom election was held on 5 May. In down to the normal difficulties of a government remaining 2001, victory in 330 of 659 seats was required to gain a in power for a substantial time. Early in 2005, David House of Commons majority. In 2005, with Scottish seats Sanders of Essex University calculated that the reduced to 59 (-13) as an offset for an increase in the size Government had lost 0.06 per cent each month it had been of the Scottish Parliament, victory in 324 seats would give in office.3 It was clear, however, that an important factor a party control of the new House of 646 members. was the decline in Blair’s standing. By early 2005, only The state of the parties 32 per cent of those surveyed by a MORI poll said they 4 More than 3500 candidates from 170 parties nominated. trusted him. The Sunday Times assessment was blunt: Tony Blair’s Labour Government held 408 seats; a loss of For many voters smiling, fresh-faced Blair Mark I has been 85 would put it in a minority position. The Conservatives, replaced by a soapy-looking, swivel-eyed purveyor of untruths.5 under Michael Howard, needed to double their 162 seats to Related to this was the increasing tension in the Labour gain control of the Commons. The Liberal Democrats led Party caused by the deterioration in the relationship by Charles Kennedy held 55 seats. -

Cross-Border Provision of Public Services for Wales: Transport

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee Cross-border provision of public services for Wales: Transport Tenth Report of Session 2008–09 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 7 July 2009 HC 58 Incorporating HC 401 xiii-xvi, Session 2007-08 Published on 17 July 2009 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Welsh Affairs Committee The Welsh Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Office of the Secretary of State for Wales (including relations with the National Assembly for Wales). Current membership Dr Hywel Francis MP (Labour, Aberavon) (Chairman) Mr David T.C. Davies MP (Conservative, Monmouth) Ms Nia Griffith MP (Labour, Llanelli) Mrs Siân C. James MP (Labour, Swansea East) Mr David Jones MP (Conservative, Clwyd West) Mr Martyn Jones MP (Labour, Clwyd South) Rt Hon Alun Michael MP (Labour and Co-operative, Cardiff South and Penarth) Mr Albert Owen MP (Labour, Ynys Môn) Mr Mark Pritchard MP (Conservative, The Wrekin) Mr Mark Williams MP (Liberal Democrat, Ceredigion) Mr Hywel Williams MP (Plaid Cymru, Caernarfon) Powers The committee is one of the Departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/welsh_affairs_committee.cfm. -

Lawless World - the Ub Sh Administration and Iraq: Issues of International Legality and Criminality Philippe Sands

Hastings International and Comparative Law Review Volume 29 Article 1 Number 3 Spring 2006 1-1-2006 Lawless World - The uB sh Administration and Iraq: Issues of International Legality and Criminality Philippe Sands Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_international_comparative_law_review Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Philippe Sands, Lawless World - The Bush Administration and Iraq: Issues of International Legality and Criminality, 29 Hastings Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 295 (2006). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_international_comparative_law_review/vol29/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Nov. 2005 Rudolf B. Schlesinger Lecture on International and Comparative Law Lawless World? The Bush Administration and Iraq: Issues of International Legality and Criminality By PROFESSOR PHILIPPE SANDS QC* Dean, Professor, students, I feel greatly privileged to have been invited to speak this afternoon on the subject of America's engagement with international law. I will focus on issues of legality and criminality arising in the context of the war in Iraq. When I was invited to give this lecture, issues of legality and Iraq were very much in the air in Britain. The May 2005 General Election was dominated by Iraq, and in particular the circumstances in which the British Prime Minister took Britain to war. -

The Conservatives and the Electoral System

October 2005 The Conservatives and the electoral system Foreword This paper is intended to inform and provoke debate within the Conservative Party and amongst its supporters on the case for changing our voting system. It has been written by Lewis Baston, the Research and Information Officer of the Electoral Reform Society, on behalf of both the Society and Conservative Action for Electoral Reform (CAER). It examines the large pro-Labour bias in the First- Past- the-Post (FPTP) electoral system currently in use for elections to the House of Commons. It looks at the results of the election in terms of national and regional representation before examining the nature, history and current extent of bias between the two main parties. Many Conservatives since the election have expressed the hope that the forthcoming review of parliamentary boundaries will solve the bias problem.This paper examines the progress of the review and the impact of the current proposals for new boundaries on the strength of the parties, before examining the possibilities for a more radical change in the way parliamentary boundaries are drawn. However, boundary determination is only a small factor in generating bias, and the more powerful reasons – differential turnout and the distribution of the vote – that are mostly responsible. Given all the problems that exist for the Conservatives under FPTP,the arguments for a reformed electoral system that relates seats more directly to votes are stronger than ever, for both pragmatic and principled reasons.The alternatives – hoping that something will turn up, gerrymandering, or getting used to being a permanent minority party – are not very attractive ones. -

Robert SHEEHAN Conor MACNEILL

Conor Robert MACNEILL INVISIBLE SUN SHEEHAN WHEN THE TROUBLES ENDED THE TRUE FIGHT BEGAN SEVEN & Coming 2016 7 SEVEN 7 PRODUCERS SALES SERVICE from the award winning talent of writer Conor MacNeill, director David Blair and producer Mike Knowles Synopsis In a desperate attempt to help save his is lured by the prospect of easy money Then comes news that little Seamus the pressure building and faced with a family’s home from repossession a young running pills for local pusher YAZZER, has been found dead, killed by a drug final foreclosure notice from the bank, man turns to running drugs, but following a young, violent and unpredictable overdose. Ciaran realizes to his horror Ciaran pulls off one last big drug deal a child’s overdose he finds himself gangster. that some pills went missing when with a dangerous Loyalist gang that will pursued by vigilantes including his own Seamus and Ryan took his bag. His earn thousands of pounds. Meanwhile, unsuspecting father. Ciaran is spotted dealing in the street drugs had killed Claire’s little brother. following a case of mistaken identity, by two boys SEAMUS and RYAN Word spreads like wild fire through the Michael and the vigilantes accidentally CIARAN, a working class Catholic who playfully swipe his bag. Seamus council estate where anger over the execute Yazzer, but not before he lad, struggles to find his way in post- blackmails Ciaran not to reveal his past is still raw. Frustrated with the has revealed the truth about Ciaran’s conflict Belfast. His father MICHAEL, activities to older sister CLAIRE, a current political leadership, a gang of activities. -

General Elections in the Post-Devolution Period: Press Accounts of the 2001 and 2005 Campaigns in Scotland and England

General elections in the post-devolution period: press accounts of the 2001 and 2005 campaigns in Scotland and England Marina Dekavalla Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Stirling Department of Film, Media and Journalism December 2009 © Marina Dekavalla 2009 Abstract This thesis examines and compares newspaper coverage of the first two general elections after Scottish devolution, looking at both the Scottish and English/UK press. By considering the coverage of a major political event which affects both countries, it contributes to debates regarding the performance of the Scottish press within an arguably distinct Scottish public sphere as well as that of the press in England within a post-devolution context. The research is based on a content analysis of all the coverage of the 2001 and 2005 elections in seven Scottish and five English and UK daily morning newspapers, a critical discourse analysis of a sample of the coverage of the most mentioned issues in each campaign and a small set of interviews with Scottish political editors. As a framework for its analysis, this thesis focuses on theories of national identity and deliberative democracy in the media. It finds that the coverage of elections in the two countries has a similar issue agenda, however Scottish newspapers appear less interested in the UK aspect of the elections and include debates on Scottish affairs which are discussed in isolation, within an exclusively Scottish mediated space. These issues are constructed as particularly relevant to a Scottish readership through references to the nation, inclusive modes of address to the reader and the inclusion of exclusively Scottish sources, which contrast with the Scottish coverage of “UK” issues.