The Mutomo Hill Plant Sanctuary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scripture Translations in Kenya

/ / SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA by DOUGLAS WANJOHI (WARUTA A thesis submitted in part fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in the University of Nairobi 1975 UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI LIBRARY Tills thesis is my original work and has not been presented ior a degree in any other University* This thesis has been submitted lor examination with my approval as University supervisor* - 3- SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA CONTENTS p. 3 PREFACE p. 4 Chapter I p. 8 GENERAL REASONS FOR THE TRANSLATION OF SCRIPTURES INTO VARIOUS LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS Chapter II p. 13 THE PIONEER TRANSLATORS AND THEIR PROBLEMS Chapter III p . ) L > THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TRANSLATORS AND THE BIBLE SOCIETIES Chapter IV p. 22 A GENERAL SURVEY OF SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA Chapter V p. 61 THE DISTRIBUTION OF SCRIPTURES IN KENYA Chapter VI */ p. 64 A STUDY OF FOUR LANGUAGES IN TRANSLATION Chapter VII p. 84 GENERAL RESULTS OF THE TRANSLATIONS CONCLUSIONS p. 87 NOTES p. 9 2 TABLES FOR SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN AFRICA 1800-1900 p. 98 ABBREVIATIONS p. 104 BIBLIOGRAPHY p . 106 ✓ - 4- Preface + ... This is an attempt to write the story of Scripture translations in Kenya. The story started in 1845 when J.L. Krapf, a German C.M.S. missionary, started his translations of Scriptures into Swahili, Galla and Kamba. The work of translation has since continued to go from strength to strength. There were many problems during the pioneer days. Translators did not know well enough the language into which they were to translate, nor could they get dependable help from their illiterate and semi literate converts. -

Linguistic Outcomes of Sabaot/Kiswahili Contact in Mt

LINGUISTIC OUTCOMES OF SABAOT/KISWAHILI CONTACT IN MT. ELGONSUB-COUNTY, BUNGOMA COUNTY, KENYA BY MACHANI ABRAHAM, BED (Arts) C50/CE/25338/2013 A DISSERTATIONSUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF ARTS OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY JULY, 2017 DECLARATION This is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any University. Signature __________________ Date__________________ MACHANI ABRAHAM C50/CE/25338/2013 This dissertation has been submitted with our approval as the University supervisors. Signature __________________ Date___________________ DR. KEBEYA HILDA DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LINGUISTICS KENYATTA UNIVERSITY Signature __________________ Date___________________ DR. SHIVACHI CALEB DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LINGUISTICS KENYATTA UNIVERSITY ii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to Sharon, my lovely wife, and Israella, our dear daughter. They encouraged me and gave me the moral support while I was carrying out this research. I also dedicate it to my parents for bringing me up and educating me. iii ACKNOWLEGEMENT I take this opportunity to thank the Management of Kenyatta University for according me an opportunity to study in this great Institution. Special recognition goes to my supervisors Dr.Kebeya Hilda and Dr.Shivachi Caleb for giving me the necessary guidance throughout my research period.May God blessyou. Finally, I thank the Almighty God for the strength and good health which enhanced my completion of this research. iv ABSTRACT This study is an analysis of lexical borrowing of nominals in Sabaot from Kiswahili. The two languages under study differ from each other in significant ways. -

Impacts of Colonial Policies and Practices on Kamba Song and Dance up to 1945

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 25, Issue 4, Series. 5 (April. 2020) 18-25 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Impacts of Colonial Policies and Practices on Kamba Song and dance Up To 1945. Kilonzo Josephine Katiti Abstract: Song and dance are powerful cultural medium in any society. This is especially so in countries where other forms of communication and cultural expression, such as written word are not yet fully developed. The history of many developing countries where colonial domination was evidenced indicates that the colonized people were always able to express themselves through song and dance in complete defiance of the oppressor. Song and dance was used not just as a preserver but also a transmitter of history. This paper seeks to assess the impacts of colonial policies and practices on Kamba song and dance up to 1945. Due to the view of the colonizers that the Africans were primitive and barbaric the colonial masters introduced policies which favored them. These policies led to a definite change of the content of Kamba songs sang at that time. In order to accommodate the changes to the environment, culture, political and economic life of the community, several changes were experienced at the time. This paper present the findings from the study that was conducted on the Kamba of eastern Kenya and shows that over time the community evolved dynamic song and dance styles that responded to the changes within their midst. This paper hopes to contribute to scholarship in terms of the key contribution of Kamba song to the historical transformation of society. -

Race for Distinction a Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya

Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 09 December 2015 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Stephen Smith (EUI Supervisor) Prof. Laura Lee Downs, EUI Prof. Romain Bertrand, Sciences Po Prof. Daniel Branch, Warwick University © Connan, 2015 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Race for Distinction. A Social History of Private Members’ Clubs in Colonial Kenya This thesis explores the institutional legacy of colonialism through the history of private members clubs in Kenya. In this colony, clubs developed as institutions which were crucial in assimilating Europeans to a race-based, ruling community. Funded and managed by a settler elite of British aristocrats and officers, clubs institutionalized European unity. This was fostered by the rivalry of Asian migrants, whose claims for respectability and equal rights accelerated settlers' cohesion along both political and cultural lines. Thanks to a very bureaucratic apparatus, clubs smoothed European class differences; they fostered a peculiar style of sociability, unique to the colonial context. Clubs were seen by Europeans as institutions which epitomized the virtues of British civilization against native customs. In the mid-1940s, a group of European liberals thought that opening a multi-racial club in Nairobi would expose educated Africans to the refinements of such sociability. -

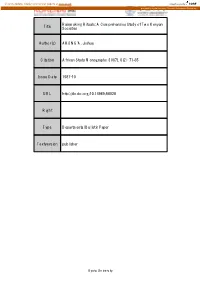

A Comprehensive Study of Two Kenyan Societies Author(S)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Rainmaking Rituals: A Comprehensive Study of Two Kenyan Title Societies Author(s) AKONG'A, Joshua Citation African Study Monographs (1987), 8(2): 71-85 Issue Date 1987-10 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68028 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study "'tonographs, 8(2): 71-85, October 1987 71 RAINMAKING RITUALS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TWO KENYAN SOCIETIES Joshua AKONG'A Instilute ofAfrican Stlldies. Unh'ersity ofNairobi ABSTRACf A comparative examination of the public rainmaking rituals in Kitui District and the secret rainmaking rituals in Bunyore location of Kakamega District, both in Kenya, reveals that public rituals are more susceptible to rapid social change than those of secret. Secondly. although rainmaking rituals are a response to scarcity or unreliability that are rain fall. such rituals can be found even in the areas of adequate rainfall either because the people once lived in an area of rainfall scarcity or the rainmakers are strangers who came from such areas. Thirdly, the efficacy of rainmaking rituals is based on faith, and due to the involvement of the supernatural, they have socio-psychological implications on the participants. Key Words: Rainmaking; Processions; Magic; Prophesy; Occult. INTRODUCTION Sir James George Frazer who wrote widely on the types and practices of magic, considered rainfall rituals as falling under the purview of magic. This is because the purpose of rainfall rituals is to influence weathercondition~ in order to cause rain or to cause drought either for the general good or destruction ofthe people in the specific society in which there is a belief in man's ability to influence weather conditions. -

Journal of Arts & Humanities

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 07, Issue 11, 2018: 58-67 Article Received: 06-09-2018 Accepted: 02-10-2018 Available Online: 23-11-2018 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v7i10.1491 Pioneering a Pop Musical Idiom: Fifty Years of the Benga Lyrics 1 in Kenya Joseph Muleka2 ABSTRACT Since the fifties, Kenya and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have exchanged cultural practices, particularly music and dance styles and dress fashions. This has mainly been through the artistes who have been crisscrossing between the two countries. So, when the Benga musical style developed in the sixties hitting the roof in the seventies and the eighties, contestations began over whether its source was Kenya or DRC. Indeed, it often happens that after a musical style is established in a primary source, it finds accommodation in other secondary places, which may compete with the originators in appropriating the style, sometimes even becoming more committed to it than the actual primary originators. This then begins to raise debates on the actual origin and/or ownership of the form. In situations where music artistes keep shuttling between the countries or regions like the Kenya and DRC case, the actual origin and/or ownership of a given musical practice can be quite blurred. This is perhaps what could be said about the Benga musical style. This paper attempts to trace the origins of the Benga music to the present in an effort to gain clarity on a debate that has for a long time engaged music pundits and scholars. -

CHEROTICH MUNG'ou.Pdf

THE ROLE OF INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES IN PEACEBUILDING IN MOUNT ELGON REGION, KENYA BY CHEROTICH MUNG’OU A Thesis submitted to the Institute of Postgraduate Studies and Research, in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies of Kabarak University June, 2016 DECLARATION PAGE Declaration I hereby declare that this research thesis is my own original work and to the best of my knowledge has not been presented for the award of a degree in any university or college. Student’s Signature: Student’s Name: Cherotich Mung’ou Registration No: GDE/M/1265/09/11 Date: 30thJune, 2016 i RECOMMENDATION PAGE To the Institute of Postgraduate Studies and Research: The thesis entitled “The Role of Information and Communication Technologies in Peacebuilding in Mt Elgon Region, Kenya” and written by Cherotich Mung’ou is presented to the Institute of Postgraduate Studies and Research of Kabarak University. We have reviewed the thesis and recommend it be accepted in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies. 24th June, 2016 Dr. Tom Kwanya Senior Lecturer, The Technical University of Kenya 30th June, 2016 ____________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Joseph Osodo Lecturer, Maseno University ii Acknowledgement I am greatly indebted to various individuals for the great roles they played throughout my research undertaking. Most importantly, I thank God for the far He has brought me. My first gratitude goes to my supervisors Dr Tom Kwanya and Dr Joseph Osodo for their tireless effort in reviewing my work. I appreciate your intellectual advice and patience. -

Cophylogeny of Figs, Pollinators, Gallers, and Parasitoids

GRBQ316-3309G-C17[225-239].qxd 09/14/2007 9:52 AM Page 225 Aptara Inc. SEVENTEEN Cophylogeny of Figs, Pollinators, Gallers, and Parasitoids SUMMER I. SILVIEUS, WENDY L. CLEMENT, AND GEORGE D. WEIBLEN Cophylogeny provides a framework for the study of historical host organisms and their associated lineages is the first line of ecology and community evolution. Plant-insect cophylogeny evidence for cospeciation. On the other hand, phylogenetic has been investigated across a range of ecological conditions incongruence may indicate other historical patterns of associ- including herbivory (Farrell and Mitter 1990; Percy et al. ation, including host switching. When host and associate 2004), mutualism (Chenuil and McKey 1996; Kawakita et al. topologies and divergence times are more closely congruent 2004), and seed parasitism (Weiblen and Bush 2002; Jackson than expected by chance (Page 1996), ancient cospeciation 2004). Few examples of cophylogeny across three trophic lev- may have occurred. Incongruence between phylogenies els are known (Currie et al. 2003), and none have been studies requires more detailed explanation, including the possibility of plants, herbivores, and their parasitoids. This chapter that error is associated with either phylogeny estimate. Ecolog- compares patterns of diversification in figs (Ficus subgenus ical explanations for phylogenetic incongruence include Sycomorus) and three fig-associated insect lineages: pollinat- extinction, “missing the boat,” host switching, and host-inde- ing fig wasps (Hymenoptera: Agaonidae: Agaoninae: Cer- pendent speciation (Page 2003). “Missing the boat” refers to atosolen), nonpollinating seed gallers (Agaonidae: Sycophagi- the case where an associate tracks only one of the lineages fol- nae: Platyneura), and their parasitoids (Agaonidae: lowing a host-speciation event. -

Towards a Participatory Approach to Bible Translation (PABT)

TRANSLATING JONAH’S NARRATION AND POETRY INTO SABAOT Towards a Participatory Approach to Bible Translation (PABT) BY DIPHUS CHOSEFU CHEMORION DISSERTATION PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY AT STELLENBOSCH UNIVERSITY PROMOTER: Prof. L.C. JONKER CO-PROMOTER: Prof. C.H.J. VAN DER MERWE MARCH 2008 ii DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. SIGNED:_____________________ DATE: 22 February 2008 Copyright © 2008 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved iii ABSTRACT TRANSLATING JONAH’S NARRATION AND POETRY INTO SABAOT: Towards a Participatory Approach to Bible Translation (PABT) By Diphus Chosefu Chemorion Recent developments in the field of translation studies have shown that a single translation of the Bible cannot be used for all the functions for which people may need a translation of the Bible. Unlike the case in the past when new versions of the Bible were viewed with suspicion, it is now increasingly acknowledged that different types of the Bible are necessary for different communicative functions. While many African communities have only a pioneer mother tongue translation of the Bible, Scripture use reports indicate that in some situations, the mother tongue translations have not been used as it was intended. The writer of this dissertation supports the view that some of the Christians in their respective target language communities do not use available mother tongue translations because they find them to be inappropriate for their needs. -

Revision of the Genus Ficus L. (Moraceae) in Ethiopia (Primitiae Africanae Xi)

582.635.34(63) MEDEDELINGEN LANDBOUWHOGESCHOOL WAGENINGEN • NEDERLAND • 79-3 (1979) REVISION OF THE GENUS FICUS L. (MORACEAE) IN ETHIOPIA (PRIMITIAE AFRICANAE XI) G. AWEKE Laboratory of Plant Taxonomy and Plant Geography, Agricultural University, Wageningen, The Netherlands Received l-IX-1978 Date of publication 27-4-1979 H. VEENMAN & ZONEN B.V.-WAGENINGEN-1979 BIBLIOTHEEK T)V'. CONTENTS page INTRODUCTION 1 General remarks 1 Uses, actual andpossible , of Ficus 1 Method andarrangemen t ofth e revision 2 FICUS L 4 KEY TOTH E FICUS SPECIES IN ETHIOPIA 6 ALPHABETICAL TREATMENT OFETHIOPIA N FICUS SPECIES 9 Ficus abutilifolia (MIQUEL)MIQUEL 9 capreaefolia DELILE 11 carica LINNAEUS 15 dicranostyla MILDBRAED ' 18 exasperata VAHL 21 glumosu DELILE 25 gnaphalocarpa (MIQUEL) A. RICHARD 29 hochstetteri (MIQUEL) A. RICHARD 33 lutea VAHL 37 mallotocarpa WARBURG 41 ovata VAHL 45 palmata FORSKÀL 48 platyphylla DELILE 54 populifolia VAHL 56 ruspolii WARBURG 60 salicifolia VAHL 62 sur FORSKÂL 66 sycomorus LINNAEUS 72 thonningi BLUME 78 vallis-choudae DELILE 84 vasta FORSKÂL 88 vogelii (MIQ.) MIQ 93 SOME NOTES ON FIGS AND FIG-WASPS IN ETHIOPIA 97 Infrageneric classification of Hewsaccordin gt o HUTCHINSON, related to wasp-genera ... 99 Fig-wasp species collected from Ethiopian figs (Agaonid associations known from extra- limitalsample sadde d inparentheses ) 99 REJECTED NAMES ORTAX A 103 SUMMARY 105 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 106 LITERATURE REFERENCES 108 INDEX 112 INTRODUCTION GENERAL REMARKS Ethiopia is as regards its wild and cultivated plants, a recognized centre of genetically important taxa. Among its economic resources, agriculture takes first place. For this reason, a thorough knowledge of the Ethiopian plant cover - its constituent taxa, their morphology, life-cycle, cytogenetics etc. -

Weiblen, G.D. 2002 How to Be a Fig Wasp. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 47:299

25 Oct 2001 17:34 AR ar147-11.tex ar147-11.sgm ARv2(2001/05/10) P1: GJB Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2002. 47:299–330 Copyright c 2002 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved ! HOW TO BE A FIG WASP George D. Weiblen University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Biology, St. Paul, Minnesota 55108; e-mail: [email protected] Key Words Agaonidae, coevolution, cospeciation, parasitism, pollination ■ Abstract In the two decades since Janzen described how to be a fig, more than 200 papers have appeared on fig wasps (Agaonidae) and their host plants (Ficus spp., Moraceae). Fig pollination is now widely regarded as a model system for the study of coevolved mutualism, and earlier reviews have focused on the evolution of resource conflicts between pollinating fig wasps, their hosts, and their parasites. Fig wasps have also been a focus of research on sex ratio evolution, the evolution of virulence, coevolu- tion, population genetics, host-parasitoid interactions, community ecology, historical biogeography, and conservation biology. This new synthesis of fig wasp research at- tempts to integrate recent contributions with the older literature and to promote research on diverse topics ranging from behavioral ecology to molecular evolution. CONTENTS INTRODUCING FIG WASPS ...........................................300 FIG WASP ECOLOGY .................................................302 Pollination Ecology ..................................................303 Host Specificity .....................................................304 Host Utilization .....................................................305 -

Free Download From

Free download from www.hsrcpress.ac.za Free download Free download from www.hsrcpress.ac.za Free download Free download from www.hsrcpress.ac.za Free download Published by HSRC Press Private Bag X9182, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa www.hsrcpress.ac.za First published 2010 ISBN (soft cover) 978-0-7969-2322-6 ISBN (pdf) 978-0-7969-2323-3 ISBN (e-pub) 978-0-7969-2324-0 © 2010 Human Sciences Research Council The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily Free download from www.hsrcpress.ac.za Free download reflect the views or policies of the Human Sciences Research Council (‘the Council’) or indicate that the Council endorses the views of the authors. In quoting from this publication, readers are advised to attribute the source of the information to the individual author concerned and not to the Council. Copyedited by Lee Smith Typeset by Robin Taylor Cover design by FUEL Design Printed by [Name of printer, city, country] Distributed in Africa by Blue Weaver Tel: +27 (0) 21 701 4477; Fax: +27 (0) 21 701 7302 www.oneworldbooks.com Distributed in Europe and the United Kingdom by Eurospan Distribution Services (EDS) Tel: +44 (0) 20 7240 0856; Fax: +44 (0) 20 7379 0609 www.eurospanbookstore.com Distributed in North America by Independent Publishers Group (IPG) Call toll-free: (800) 888 4741; Fax: +1 (312) 337 5985 www.ipgbook.com Contents Tables and figures vii Acronyms and abbreviations viii Acknowledgements x Foreword xi Introduction: The struggle over land in Africa: Conflicts, politics and change