Hogshaw Geophysics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Bucks Rripple (Ramblers Repairing & Improving Public Paths

North Bucks rRIPPLE (ramblers Repairing & Improving Public Paths for Leisure & Exercise) Activity Report 22 September 2016 – 13 November 2016 Before & after photos of all work are available on request. Man hours include some travel time. DaG = Donate a Gate. CAMS is a reference used by BCC/Ringway Jacobs for work requests. All work is requested and authorised by Alastair McVail, Ringway Jacobs, North Bucks RoW Officer, or Jon Clark, BCC Access Officer. 22/9/16 Took delivery of 7 Marlow and 3 Woodstock kissing gates from BCC/TfB at CRFC. Good chat with Greg & Bill of TfB regarding gate installation and their preferred installation method using a timber post attached to either side of a gate. Not so critical with kissing gates. 22/9/16 Stewkley. Emailed Alastair McVail re the replacement by TfB of our gate with a kissing gate at SP842264 to appease Mrs Carter. (See 9/8/16 CAMS 81198). 23/9/16 Eythrop. Emailed Jon Clark reCAMS 81845 at SP768134 completed on 3/2/16 as way marker has been knocked down again. 26/9/16 Eythrop. Received CAMS 83629 at SP768134 to rerect snapped of at ground level way marker post - hit by a vehicle. 27/9/16 Mentmore. CAMS 82567 at SP907186 on MEN/8/1 installed way mark post and bridleway way marker discs. Liaised with golf club groundsman, Adam. Two x 2.5 = 5.0 man hours. B&J. 27/9/16 Mentmore. CAMS 82569 at SP889192 and at SP892194 on MEM/15/2. Checked functioning of two timber kissing gates. First one needed timber attaching to post to prevent gate from swinging right through, second considered to be okay. -

1 Buckinghamshire; a Military History by Ian F. W. Beckett

Buckinghamshire; A Military History by Ian F. W. Beckett 1 Chapter One: Origins to 1603 Although it is generally accepted that a truly national system of defence originated in England with the first militia statutes of 1558, there are continuities with earlier defence arrangements. One Edwardian historian claimed that the origins of the militia lay in the forces gathered by Cassivelaunus to oppose Caesar’s second landing in Britain in 54 BC. 1 This stretches credulity but military obligations or, more correctly, common burdens imposed on able bodied freemen do date from the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of the seventh and eight centuries. The supposedly resulting fyrd - simply the old English word for army - was not a genuine ‘nation in arms’ in the way suggested by Victorian historians but much more of a selective force of nobles and followers serving on a rotating basis. 2 The celebrated Burghal Hidage dating from the reign of Edward the Elder sometime after 914 AD but generally believed to reflect arrangements put in place by Alfred the Great does suggest significant ability to raise manpower at least among the West Saxons for the garrisoning of 30 fortified burghs on the basis of men levied from the acreage apportioned to each burgh. 3 In theory, it is possible that one in every four of all able-bodied men were liable for such garrison service. 4 Equally, while most surviving documentation dates only from 1 G. J. Hay, An Epitomised History of the Militia: The Military Lifebuoy, 54 BC to AD 1905 (London: United Services Gazette, 1905), 10. -

Buckinghamshire. [Kelly's

120 HOGGESTON. BUCKINGHAMSHIRE. [KELLY'S Charles Il. and rector of this parish, who died 2oth The land is principally pasture, but wheat, oats and Nov. r68o. and his son and successor, Charles Gataker, beans are grown in small quantities. The area is 1,571 equally celebrated as a critic and divine, who died acres; mteable value, £1,472; the population in 19rr Nov. wtb, 17or, are both buried in the chancel. In was 138. the village i!l a Reading-room, open during the winter Sexton, Henry Baker. evenings. The Earl of Rosebery K.G., K.T., P.C.. Lett~n through Winslow arrive at 7.ro a.m. & 6.30 F.S.A. is lord of the manor and owns all the land with p.m. week days; sundayR, 8.30 a.m. Wall Letter Box the exception of the glebe. The old Manor House, an ( cleared week days at 7.15 a.m. & 6-4o p.m.; sundays interesting building in the Domestic Gothic style and I at 8.40 a.m. Winslow is the nearest money order t dating from about the r6th century, has a good panelled 1 telegraph office, about 3! miles dist-ant room, massive oak stairs and fine chimneys, and is no" Eh"lmentary School (mixed), for so children; Miu occupied by Mr. Blick Morris, in whose family it has re Wilkin&, mi~tress; Miss Alice Margaret Baylis, cor- mained for 200 year!!. The soil is clay; subsoil, clay res.pondent Walpole Rev. Arthur Sumner :M.A.. 1 COMMERCIAL .!\lorris Blick, farmer, Manor honss (rector), The Rectory · Chapman Wm. -

210809 August Planning PC Agenda

Granborough Parish Council Clerk to the Council Mrs Victoria Firth All Councillors You are hereby summoned to the Meeting of Granborough Parish Council to be held on Monday 9th August 2021, in The Village Hall, commencing at 7.30pm for the purpose of transacting the following business: AGENDA 95. Receive Apologies; to accept apologies for absence 96. Open Forum for Parishioners; residents can comment on any item of council business 97. Declaration of interest in items on the agenda; To declare any interest in Agenda Items 98. To confirm the Minutes of the last meeting; 13th July 2021 99. Planning; a. To agree a Consultee response to application 21/02817/ALB at 17 Winslow Road, for proposed drainage works. b. To agree a Consultee response to application 21/02805/APP at 10 Church Lane for raised roof extension and new front porch. c. To agree a Consultee response to application 21/02960/APP at Land Off Hogshaw Road for conversion of timber barn for residential let or holiday let. d. To receive a status update from public access on planning book applications 100. Neighbourhood Plan; To endorse the Final Neighbourhood Plan document 101. Post and Consultations; a. Various NALC Communications and Updates b. 15/7 NBPPC Minutes c. 15/7 WAVCM Covid Briefings d. 16/7 BALC Annual Conference Notification e. 17/7 NBPPC various communications regarding involvement in future consultations f. 18/7 Unity Bank FSCS protection g. 23/7 2 year old funding communication h. 26/7 NBPPC – Changes to public access i. 28/7 Heart of Bucks Love Bucks Appeal j. -

Buckinghamshire

Archaeological Investigations Project 2003 Post-Determination & Non-Planning Related Projects South East BUCKINGHAMSHIRE Aylebury Vale 3/763 (E.11.M019) SP 73732250 MK18 3LA CLAYDON ROAD, HOGSHAW Watching Brief and Salvage Recording: Claydon Road, Hogshaw, Buckinghamshire Fell, D Milton Keynes : Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd., 2003, 39pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd A number of archaeological remains were observed, notably a group of medieval buildings adjacent to Claydon Road, which may have been buildings associated with the Knights Hospitallers were also observed in the northern part of the site. A number of finds, including an assemblage of medieval pottery were also recorded. [Au(abr)] Archaeological periods represented: MD, PM 3/764 (E.11.Q003) SP 79303080 MK17 0PE 25 WOOD END, LITTLE HORWOOD Report on an Archaeological Watching Brief at Stables, 25 Wood End, Little Horwood, Buckinghamshire Lisboa, IMilton Keynes : Archaeologica, 2003, 27pp, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeologica A watching brief identified four ditches and two pits of unknown date. Roman pottery was present with roof and floor tiles which could have suggested the location of a Roman building in the vicinity of the site. A flint knife, dating to the Neolithic/Early Bronze Age, was also present on the site. [AIP] SMR primary record number:BC20675, CAS Archaeological periods represented: PR, RO, UD 3/765 (E.11.M017) SP 79303070 MK17 0PE 3 WOOD END, LITTLE HORWOOD Watching Brief: 3 Wood End, Little Horwood, Buckinghamshire Hunn, J Milton Keynes : Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd., 2003, 18pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Services & Consultancy Ltd The site had been truncated in the past and the ground partly filled in with modern building rubble. -

Directory of Organisations Supporting Older People in Areas Around Buckingham¹

Directory of organisations supporting older people in areas around Buckingham¹ Haddenham² and Winslow³ ¹ Addington, Adstock, Akeley, Barton Hartshorn, Beachampton, Biddlesden, Buckingham, Calvert, Charndon, Chetwode, East Claydon, Foscott, Gawcott with Lenborough, Hillesden, Hogshaw, Leckhampstead, Lillingstone Dayrell with Luffield Abbey, Lillingstone Lovell, Maids Moreton, Middle Claydon, Nash, Padbury, Poundon, Preston Bissett, Radclive-cum-Chackmore, Shalstone, Steeple Claydon, Stowe, Thornborough, Thornton, Tingewick, Turweston, Twyford, Water Stratford, Westbury and Whaddon. ² Aston Sandford, Boarstall, Brill, Chearsley, Chilton, Cuddington, Dinton-with-Ford and Upton, Haddenham, Ickford, Kingsey, Long Crendon, Oakley, Shabbington, Stone with Bishopstone and Hartwell, and Worminghall ³ Creslow, Dunton, Granborough , Great Horwood , Hardwick, Hoggeston, Little Horwood , Mursley, Newton Longville , North Marston , Oving , Pitchcott, Swanbourne, Whitchurch and Winslow This pack is produced as part of the Building Community Capacity Project by AVDC’s Lynne Maddocks. Contact on 01296 585364 or [email protected] for more information. July 2013 Index All groups are listed alphabetically according to organisation name. This list is not a fully comprehensive listing of older people’s services in these areas, but is designed to be a good starting point. Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of this information. It is up to date at the time of printing which is July 2013. Page No Organisation name 4 Abbeyfield (Haddenham) -

High Speed Rail (London

HIGH SPEED RAIL (London - West MidLands) equaLity Impact assessMent update: cFa2 caMden toWn - cFa26 WashWood heath to curzon street deposit Locations The following locations hold hard-copy versions of the consultation documents LIBRARIES Swiss Cottage Central Library, 88 Avenue Road, London NW3 3HA Camden Town Library, Crowndale Centre 218 Eversholt Street, London NW1 1BD Kentish Town Library, 262-266 Kentish Town Road, London NW5 2AA Kilburn Leisure Centre, 12-22 Kilburn High Road, London NW6 5UH Shepherds Bush Library, 6 Wood Lane , London W12 7BF Harlesden Library, Craven Park Road, London, NW10 8SE Greenford Library, Oldfield Lane South, Greenford, Middlesex, UB6 9LG Ickenham Library, Long Lane, Ickenham, Middlesex UB10 8RE South Ruislip Library, Victoria Road, South Ruislip, Middlesex HA4 0JE Harefield Library, Park Lane, Harefield, Middlesex UB9 6BJ Beaconsfield Library, Reynolds Road, Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, HP9 2NJ Buckingham Library, Verney Close, Buckingham, Buckinghamshire, MK18 1JP Amersham Library, Chiltern Avenue, Amersham, Buckinghamshire HP6 5AH Chalfont St Giles Community Library, High Street, Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire HP8 4QA Chalfont St Peter Community Library, High Street, Chalfont St Peter, Buckinghamshire SL9 9QA Little Chalfont Community Library, Cokes Lane, Little Chalfont, Amersham, Buckinghamshire HP7 9QA Chesham Library and Study Centre, Elgiva Lane, Chesham, Buckinghamshire HP5 2JD Great Missenden Library, High Street, Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire HP16 0AL Aylesbury Study Centre, County -

Late Medieval Buckinghamshire

SOLENT THAMES HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH FRAMEWORK RESOURCE ASSESSMENT MEDIEVAL BUCKINGHAMSHIRE (AD 1066 - 1540) Kim Taylor-Moore with contributions by Chris Dyer July 2007 1. Inheritance Domesday Book shows that by 1086 the social and economic frameworks that underlay much of medieval England were already largely in place. The great Anglo Saxon estates had fragmented into the more compact units of the manorial system and smaller parishes had probably formed out of the large parochia of the minster churches. The Norman Conquest had resulted in the almost complete replacement of the Anglo Saxon aristocracy with one of Norman origin but the social structure remained that of an aristocratic elite supported by the labours of the peasantry. Open-field farming, and probably the nucleated villages usually associated with it, had become the norm over large parts of the country, including much of the northern part of Buckinghamshire, the most heavily populated part of the county. The Chilterns and the south of the county remained for the most part areas of dispersed settlement. The county of Buckinghamshire seems to have been an entirely artificial creation with its borders reflecting no known earlier tribal or political boundaries. It had come into existence by the beginning of the eleventh century when it was defined as the area providing support to the burh at Buckingham, one of a chain of such burhs built to defend Wessex from Viking attack (Blair 1994, 102-5). Buckingham lay in the far north of the newly created county and the disadvantages associated with this position quickly became apparent as its strategic importance declined. -

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE. • [ KELLY's FARMERS-Continued

260 FAR BUCKINGHAMSHIRE. • [ KELLY'S FARMERS-continued. · Brown William {to Hon. R. E. Hubbard), Speed William (to Waiter Haze11 esq. Winter James, Ballinger, Great Mis- Addington, Winslow J.P.), Turn-furlong, Walton, Aylesbury senden R.S.O Butler Thomas (to Capt. T. H. Tyrwhitt- Stephens Thomas (to the Hon. W. F. D. Winter T. Holmer green, Amersham Drake), Mantles Green farm, Amersham Smith M.P. ), Yewden Manor farm, Winter T. Wycombe heath, Little Mis- Chappin Henry (to Lady de Rothschild), Hambleden, Henley-on-Thames send en, Amersham Aston Clinton, Aylesbury Stevens Eli (to J. T. Mills esq. ), Cherry Winterbourne James, Lillingstone Dayrell, Cherry Frank (to Messrs. Taylor & Wel- orchard, Soulbury, Leighton Buzzard Buckingham lings), Hogshaw-cum-Fulbrook, Winslw Summerford Frederick (to ].\fr. Edward Winterburn John, Akeley, Buckingham Cherry Richard (to Joseph Franklin Holdour), Cross Roads farm, Bow Withers & Patcher, Fillingdon farm, West esq.), Scotsgrove, Haddenham, Aylsbry Brickhill, Bletchley Wycombe, High Wycombe Clark George (to R. L. Ovey esq.), Tur- Sutton Arthur (to Sir Oswald 1.\Iosley Withers Edward Owen, Ashridge, Rad- ville, Henley hart.), Stoke Mandeville, Aylesbury nage, Stokenchurrh, Wallingford Clark Henry (to A. Tyrrell esq.), Hor- Thrussell Robert (to Thomas Henry Wood A. South hth. Gt. Missenden R.S.O ton, Slough Seaton esq.), 18 California, Aylesbury Wood Ferdinand William, Aston Mullins, Cordery Clement (to Capt. Richard Pure- Tompkins Robert (to Mr. Edwin Kibble), Ford, Aylesbury foy PurefoyR.N.),Shalstone,Buckinghm SwanbournP, Winslow Wood Humphry, Lavendon, Newprt.Pgnll Cordy John (to Mrs. Ellen Chapman), Tuffney William (to William F. J. Gates Wood John, Binwell lane, Doddershall, Bottom farm, Radnage, Stokenchurch, esq.), Wing, Leighton Buzzard Aylesbury Wa1lingford Turner Robert (to R. -

Fullbrook Barn, Hogshaw, Buckinghamshire, Mk18 3Jy

Fullbrook Barn, Hogshaw, Buckinghamshire, MK18 3JY Aylesbury 7 miles (Marylebone 55 mins) Bicester 15 miles (M40 Jnc 9) all distances/times approx. FULLBROOK BARN, HOGSHAW, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE, MK18 3JY IN A GLORIOUS RURAL LOCATION NESTLED UNDER THE QUAINTON HILLS, A SUPERB CONVERTED BARN SURROUNDED IN OVER TWO AND A HALF ACRES OF LAND. EXCEPTIONAL AND EXTENSIVE PANORAMIC VIEWS WITH DIRECT ACCESS TO A BRIDLEWAY THE ACCOMMODATION: Hallway, Kitchen/Breakfast Room, Sitting Room, Dining Room, Study or Family Room/Bedroom Four, Master Bedroom with Ensuite Bathroom, Guest Bedroom with Ensuite Shower Room, Third Double Bedroom, Family Bathroom OUTSIDE: Tree Lined Driveway Behind Electric Gates, Manicured Grounds, Garden Courtyard, Extensive Parking, Workshop, Two Double Garages and Store, Kennels with Grooming Room and Fenced Run, Boating Pond with Jetty FOR SALE FREEHOLD LOCATION EDUCATION Hogshaw is a civil parish within Aylesbury Vale district in Buckinghamshire, England. Primary Schools at East Claydon, Steeple Claydon & Winslow It comprises the two ancient villages of Hogshaw and Fulbrook, though neither exist in Upper School at Buckingham their entirety any more. It is in the Aylesbury Vale, between East Claydon and Preparatory schools at Ashfold, Swanbourne and Oxford Quainton. The village name 'Hogshaw' is Anglo Saxon in origin, and means 'Hogg's Public schools at Stowe, Berkhamsted and Oxford. brook' (where 'Hogg' is someone's personal name). In the Domesday Book of 1086 it Grammar Schools at Aylesbury and Buckingham. was recorded as Hoggsceaga.. Anciently the parish was in the possession of the Knights Templar, and when that order DESCRIPTION was abolished the Knights Hospitaller. It began as the Hogshaw Nunnery and then Fullbrook Barn was converted around 9 years ago by the current owners, the building became the Hogshaw Commandery in the 15th century. -

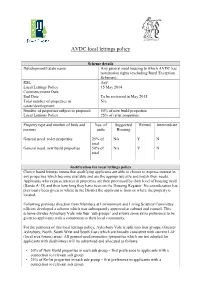

AVDC Sub Groups Local Lettings Policy

AVDC local lettings policy Scheme details Development/Estate name Any general need housing to which AVDC has nomination rights (excluding Rural Exception Schemes). RSL Any Local Lettings Policy – 15 May 2014 Commencement Date End Date To be reviewed in May 2015 Total number of properties in N/a estate/development Number of properties subject to proposed 50% of new build properties Local Lettings Policy 25% of re let properties Property type and number of beds and Nos. of Supported Rented Intermediate persons units Housing General need, re-let properties 25% of N/a Y N total General need, new build properties 50% of N/a Y N total Justification for local lettings policy Choice based lettings means that qualifying applicants are able to choose to express interest in any properties which become available and are the appropriate size and match their needs. Applicants who express interest in properties are then prioritised by their level of housing need (Bands A- D) and then how long they have been on the Housing Register. No consideration has previously been given to where in the District the applicant is from or where the property is located. Following previous direction from Members at Environment and Living Scrutiny Committee officers developed a scheme which was subsequently approved at cabinet and council. This scheme divides Aylesbury Vale into four ‘sub groups’ and allows some extra preference to be given to applicants with a connection to their local community. For the purposes of this local lettings policy, Aylesbury Vale is split into four groups, (Greater Aylesbury, North, South West and South East) which are broadly consistent with current LAF (local area forum) areas. -

Housing Land Supply Mar 2009

Aylesbury Vale District Housing Land Supply Position as at end March 2009 – prepared May 2009 Introduction This document sets out the housing land supply position in Aylesbury Vale District as at the end of March 2009. Lists of sites included in the housing land supply are given in Appendices 1, 2 and 3. Two sets of calculations are provided: firstly for the five years April 2009 to March 2014, and secondly for the five years April 2010 to March 2015. Housing requirement The housing requirement for Aylesbury Vale is set out in the South East Plan (May 2009) (SEP). The figures are as follows: 2006-2011 2011-2016 Aylesbury 3,800 4,400 Rest of District 1,100 1,100 Total 4,900 (980 per annum) 5,500 (1,100 per annum) Note – Regional policy (South East Plan policies H1, MKAV 1, 2 and 3) sets an annual average figure for the above. The phasing shown in the above table is taken from the South East Plan Panel report (para 23.41 onwards and 23.127 onwards) and will be revisited in line with the Growth Investment and Infrastructure policy approach as outlined in Policy CS14 of the Core Strategy. Housing land supply for 1st April 2009 to 31st March 2014 SEP requirement 5,260 Pre-2009 deficit* 758 Total 5 year requirement 6,018 Projected supply from existing allocated sites (see Appendix 1) 3,223 Projected supply from other deliverable sites ≥ 5 dwellings (see Appendix 2) 1,034 Projected supply from sites less than 5 dwellings (see Appendix 3) 335 Total projected supply 4,592 Projected supply as percentage of requirement 76.3% (3.8 years) *In the period 2006 to 2009 the number of housing completions in Aylesbury Vale has not met the SEP requirement for that period, and therefore an additional 758 dwellings are needed to make up the deficit.