Flirting with Time: a Review of Asymmetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Pass Info Packet 2019 4.22

Full-Access Business Pass Information For writers interested in taking their work to market one day, Lit Fest offers an opportunity to educate yourself about and connect with publishing professionals. Given the busy schedules of agents and editors, it’s a rare chance to receive their direct feedback and advice. You must purchase a Gold, Silver, Bronze, Penny, or Full-Access Business Pass before requesting a meeting with an agent. Thanks to Aevitas Creative Management for their Full Access Business Pass Sponsorship for a writer of color. We have the following agents and editors available for one-on-one meetings at Lit Fest 2021*: Friday Saturday Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday June 4 June 5 June 6 June 7 June 8 June 9 June 10 Lisa Paloma Paloma Danya Sarah Fuentes Sarah Fuentes Jamie Carr Gallagher Hernando Hernando Kukafka Malaga Sue Park Sue Park John Maas Danya Serene Hakim Serene Hakim Baldi Kukafka Angeline Angeline John Maas John Maas Rodriguez Rodriguez Malaga Baldi Malaga Baldi Tanusri Chris Parris- Chris Parris- Prasanna Lamb Lamb Matt Martz Tanusri Julie Buntin Prasanna Matt Martz June 11 June 12 June 13 Jamie Carr Eric Smith Eric Smith Serene Hakim Julie Buntin *Schedule is subject to change. LIT FEST PASSHOLDERS BEFORE MEETING WITH AN AGENT OR EDITOR Make sure you’re really ready for this. Writing is a competitive business, and agents are direct about their reactions to your work. Have you had a professional read of the work you’re submitting? Is it reasonably edited? If not, we’d recommend attending Lit Fest’s business panels first and then reaching out to agents and editors at a later date. -

TGC September 2018 Rights Guide

foreign rights September 2018 www.thegernertco.com JOHN GRISHAM #1 New York Times bestseller • Published in 40 languages • 375+ million books in print 23 October 2018 #1 New York Times bestselling author John Grisham returns to Clanton, Mississippi to tell the story of an unthinkable murder, the bizarre trial that follows it, and its profound and lasting effect on the people of Ford County. October 1946, Clanton, Mississippi Pete Banning was Clanton, Mississippi's favorite son - a decorated World War II hero, the patriarch of a prominent family, a farmer, father, neighbor, and a faithful member of the Methodist church. Then one cool October morning he rose early, drove into town, walked into the church, and calmly shot and killed his pastor and friend, the Reverend Dexter Bell. As if the murder weren't shocking enough, it was even more baffling that Pete's only statement about it - to the sheriff, to his lawyers, to the judge, to the jury, and to his family was: "I have nothing to say." He was not afraid of death and was willing to take his motive to the grave. In a major novel unlike anything he has written before, John Grisham takes us on an incredible journey, from the Jim Crow South to the jungles of the Philippines during World War II; from an insane asylum filled with secrets to the Clanton courtroom where Pete's defense attorney tries desperately to save him. Reminiscent of the finest tradition of Southern Gothic storytelling, The Reckoning would not be complete without Grisham's signature layers of legal suspense, and he delivers on every page. -

The Spring 2018 Library Newsletter

5/31/2018 BPSI Library Newsletter, Spring 2018 Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute Spring 2018 Quick Links Hanns Sachs Library Newsletter Recent Work Library News Libraries are more than about books these days. Many exhibit BPSI Home art and host concerts. They offer the free use of computers. Beside books, they loan videos, CD's, games and even cake baking tins. In keeping with the times, the BPSI library offers a In This Issue variety of videos to watch, audiotapes to listen to, recipes of Grete Bibring to try, and historic photographs to peruse. The Meet the Author most recent addition to our collection is Alex Hoffer's interview with Ana-Maria Rizutto before she left for Argentina. We have In Memoriam recently added material from our recent library program on the In the Archives Wolf-Man. Of course, there are still books to check out and journals to read. There is a computer for your use. And there What Are We Reading? is always help available from our extraordinary librarian, Olga Umansky. __________________ ~ Dan Jacobs, MD, Director of the Library Director of Library Dan Jacobs, MD In the Library The latest video in our new webcast series "The Voice of Experience" is the interview of Ana-María Rizzuto, MD, Librarian/Archivist recorded in the library last fall. Click on the image below to Olga Umansky, MLS watch. Library and Education Program Coordinator Drew Brydon, MLS Library Committee Ana-Maria Rizzuto interviewed by Axel Hoffer on Sep 15, 2017 in the BPSI Library James Barron, PhD Ellen Goldberg, PhD Malkah Notman, MD Dr. -

TGC February 2017

foreign rights February 2017 www.thegernertco.com JOHN GRISHAM #1 New York Times bestseller • Published in 40 languages • 375+ million books in print 6 June 2017 Bestselling author John Grisham stirs up trouble in paradise in his endlessly surprising new thriller: Camino Island unspools over one long summer, when a daring group of thieves pilfer five priceless handwritten F. Scott Fitzgerald manuscripts from Princeton University’s Library and send them into the rare books black market. As the FBI and a secret underground agency race to hunt them down, a young writer embarks on her own investigation into a prominent bookseller who is believed to have the precious documents. A daring heist; a young woman recruited to recover them; a beach-resort bookseller who gets more than he bargained for—all in one long summer on Camino Island. John Grisham is the author of thirty novels, one work of nonfiction, a collection of stories, and six novels for young readers. He lives in Virginia and Mississippi. www.thegernertco.com 2 fiction Jessie Chaffee, FLORENCE IN ECSTASY A visceral, vivid debut inspired by the novels of Jean Rhys, Elena Ferrante, and Catherine Lacey, that follows a troubled woman’s attempt to find herself in an unstable world Literary fiction Publisher: Unnamed Press – May 16, 2017 Editor: Chris Heiser Agent: Sarah Burnes Material: Advanced Reader’s Copy • “Jessie Chaffee's luminous debut is a hypnotic, addictive read. The shade of E. M. Forster stalks the heels of this story of one American woman at a crossroads in her life, in prose as lyrical and precise as it is evocative and haunting.” – Katherine Howe, author of The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane • “Be ready to be provoked and transported by FLORENCE IN ECSTASY, a haunting, beautiful novel of womanhood, the saints, and the mysteries of the body. -

Bookclub Suggestions

Bookclub Suggestions Three Daughters of Eve by Elif Shafak ISBN: 9781632869968 Binding: Paperback Publisher: Bloomsbury USA Pub. Date: 2019-01-22 Pages: 384 Price: $24.00 The stunning, timely new novel from the acclaimed, internationally bestselling author of The Architect's Apprentice and The Bastard of Istanbul. Peri, a married, wealthy, beautiful Turkish woman, is on her way to a dinner party at a seaside mansion in Istanbul when a beggar snatches her handbag. As she wrestles to get it back, a photograph falls to the ground--an old Polaroid of three young women and their university professor. A relic from a past--and a love--Peri had tried desperately to forget. Three Daughters of Eve is set over an evening in contemporary Istanbul, as Peri arrives at the party and navigates the tensions that simmer in this crossroads country between East and West, religious and secular, rich and poor. Over the course of the dinner, and amidst an opulence that is surely ill begotten, terrorist attacks occur across the city. Competing in Peri's mind, however, are the memories invoked by her almost-lost Polaroid, of the time years earlier when she was sent abroad for the first time, to attend Oxford University. As a young woman there, she had become friends with the charming, adventurous Shirin, a fully assimilated Iranian girl, and Mona, a devout Egyptian American. Their arguments about Islam and feminism find focus in the charismatic but controversial Professor Azur, who teaches divinity, but in unorthodox ways. As the terrorist attacks come ever closer, Peri is moved to recall the scandal that tore them all apart. -

TBT Sep-Oct 2018 for Online

Talking Book Topics September–October 2018 Volume 84, Number 5 Need help? Your local cooperating library is always the place to start. For general information and to order books, call 1-888-NLS-READ (1-888-657-7323) to be connected to your local cooperating library. To find your library, visit www.loc.gov/nls and select “Find Your Library.” To change your Talking Book Topics subscription, contact your local cooperating library. Get books fast from BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site. To use BARD, contact your local cooperating library or visit nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. The free BARD Mobile app is available from the App Store, Google Play, and Amazon’s Appstore. About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics, published in audio, large print, and online, is distributed free to people unable to read regular print and is available in an abridged form in braille. Talking Book Topics lists titles recently added to the NLS collection. The entire collection, with hundreds of thousands of titles, is available at www.loc.gov/nls. Select “Catalog Search” to view the collection. Talking Book Topics is also online at www.loc.gov/nls/tbt and in downloadable audio files from BARD. Overseas Service American citizens living abroad may enroll and request delivery to foreign addresses by contacting the NLS Overseas Librarian by phone at (202) 707-9261 or by email at [email protected]. Page 1 of 87 Music scores and instructional materials NLS music patrons can receive braille and large-print music scores and instructional recordings through the NLS Music Section. -

Book Club Sampler from SIMON & SCHUSTER January—April 2018

A SpringBook Club Sampler FROM SIMON & SCHUSTER January—April 2018 LOVE AND OTHER WORDS BEARTOWN By Christina Lauren By Fredrik Backman AVAILABLE AS A PAPERBACK ORIGINAL ON APRIL 10 AVAILABLE NOW IN HARDCOVER, PAPERBACK ON FEBRUARY 6 Childhood sweethearts reunite after a decade—and many unresolved issues—have The #1 New York Times bestselling author of A come between them. The first women’s fiction Man Called Ove returns with a winning novel novel from New York Times bestselling author about a forgotten town fractured by scandal, and the amateur hockey team that might just Christina Lauren. change everything. For readers of: Jojo Moyes, Taylor Jenkins For readers of: The Ocean at the End of the Reid, Jennifer Weiner, and Nights in Lane, Miller’s Valley, The Readers of Broken Rodanthe Wheel Recommend, and Empire Falls 9781501128011 9781501160769 ANATOMY OF A SCANDAL THE PERFECT STRANGER By Sarah Vaughan By Megan Miranda AVAILABLE IN HARDCOVER ON JANUARY 23 AVAILABLE NOW IN PAPERBACK Part courtroom drama, part portrait of a From New York Times bestselling author of All marriage, Anatomy of a Scandal is an incisive, the Missing Girls, the dark and twisty story of suspenseful page-turner about a scandal a journalist who sets out to find her missing among Britain’s privileged elite that couldn’t friend, a friend who may never have existed be more timely. at all. For readers of: The Kept Woman, For readers of: The Woman in Cabin 10, Defending Jacob, Notes on a Scandal, Gone Girl, The Winter People, and Luckiest Hausfrau, and John Grisham’s courtroom Girl Alive dramas 9781501172168 9781501108006 EVERY NOTE PLAYED THE TEA GIRL OF By Lisa Genova HUMMINGBIRD LANE AVAILABLE IN HARDCOVER ON MARCH 20 By Lisa See From neuroscientist and New York Times AVAILABLE NOW IN HARDCOVER, PAPERBACK ON APRIL 3 bestselling author of Still Alice, a powerful and heartbreaking novel about a divorced couple An unforgettable novel from New York Times whose relationship is redefined in the wake of bestselling author Lisa See that explores the a devastating ALS diagnosis. -

Dublin Literary Award 2020, Where You Can Read About This Year’S Longlisted Titles

DUBLIN Shortlist: 2 April 2020 LITERARY Winner: 10 June 2020 AWARD 156 Books 21 Languages 119 Cities 6 Judges 40 Countries 1 Winner INTERNATIONAL 2020 Full details of the 2020 Longlisted Books inside! LOSE YOURSELF IN LITERARY DUBLIN 2 www.dublinliteraryaward.ie CITY LIBRARIAN’S FOREWORD CITY LIBRARIAN’S FOREWORD Welcome to the magazine of the International Dublin Literary Award 2020, where you can read about this year’s longlisted titles. Here you can browse the virtual shelves of the world’s libraries and choose what you would like to read, then pick your own favourites from among these 156 fantastic works of fiction. All of our 21 branch libraries in In June 2019 we welcomed Emily Dublin will have these books Ruskovich, author of Idaho, to the available and you may borrow them city of Dublin as our winner. You for free from your nearest library can read an extract of her winner’s and return them to the library most speech on page 4–5 and what convenient to your home or work. inspiring words she spoke in front It’s also easy to renew loans online, of a delighted audience that night without having to worry about in the Round Room of the Mansion Mairead Owens library fines. House! Thanks must go to our Lord Dublin City Librarian Mayor Paul McAuliffe for hosting In this magazine you’ll be introduced the Award presentation in such to our six judges, including new non- beautiful surroundings. voting Chair of the judging panel, Professor Chris Morash of Trinity In June 2020 Dublin City Council College Dublin. -

Spring Into TKE for These Events!

THE 1511 South 1500 East Salt Lake City, UT 84105 InkslingerSpring Issue 2 018 801-484-9100 TKE Announces a Star-studded Literary Lineup for Early Summer: Save the Dates!!! There are, as you’re about many have come to call. to see in this spring edi- But one at a time. Or, if tion of the Inkslinger, a we’re very lucky, two in a raft of wonderful books given year. Seldom do the already out or coming to literary icons of our time TKE in April. The Over- parade through our city story by Richard Powers, and our store one after for one, is a book you’ll another. never forget and one Craig Childs Temple Grandin Michael Ondaatje Jennifer Egan Not until early this sum- that might just change Thursday, May 17 Wednesday, May 30 Saturday, May 26 Monday, June 4 mer, when, we’re thrilled your life. It, along with to say, we are hosting other fascinating, compelling or otherwise noteworthy novels and a procession of authors so fabulous that we can hardly believe our works of nonfiction, and terrifying if sometimes funny mysteries and good fortune. To begin with, there’s Michael Ondaatje. I’ve said more thrillers, will while away sleepless nights and rainy days—one of the than once that if Michael Ondaatje would just visit our store one time many wonderful things about books. before I die or retire I’d happily do either. And not only is he coming, Books like The Overstory truly are transformative; once read they but he’s doing so to present and read from an extraordinary book— will never let you go. -

June 4–June 13 Denver, Co & Virtually Everywhere

FICTION NONFICTION LIGHTHOUSE WRITERS WORKSHOP PRESENTS POETRY HYBRID DRAMATIC WRITING Ten Days of Seminars, Parties, Workshops, Agent Consultations, Readings, Salons, and More JUNE 4–JUNE 13 DENVER, CO & VIRTUALLY EVERYWHERE LIGHTHOUSE WRITERS WORKSHOP PRESENTS LIT FEST TURNS SIXTEEN THIS YEAR. Can you believe it? This baby can finally drive, and in honor of the steady glide toward adulthood, we’re planning another big party. An annual celebration of all things literary, Lit Fest started in restaurants and bars around Denver, and then moved 10 years ago to our historic house on Race Street, where it filled all the rooms and spilled outside to our trademark red-and-white tent. Last June, when the pandemic was underway, the festival went entirely virtual, spreading out to writing rooms and viewing screens across the globe. So you can see we’ve been evolving—emerging from our nomadic adolescence. And it doesn’t get much sweeter than this year’s program: 16 visiting authors, including Bryan Washington, Sarah Ruhl, Emily Rapp Black, Jaquira Díaz, Carolyn Forché, Sheila Heti, Leslie Jamison, Mat Johnson, Layli Long Soldier, Helen DeWitt, T Kira Madden, Rebecca Makkai, Gregory Pardlo, and Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi; more than a hundred craft seminars taught by talented Lighthouse faculty like Nick Arvin, Poupeh Missaghi, Diana Khoi Nguyen, and Amanda Rea; informative business panels featuring agents, editors, screenwriters, and authors; nightly conversations and roundtables featuring your favorite writers discussing art and life and distractions; and a series of eclectic readings to put an inspiring cap on it all. Join us for Lit Fest 2021, a 10-day literary extravaganza in the virtual sphere. -

Fall for the Book

Contents All About OLLI ................................................................................. iii Courses 100 Art and Music...................................................................................... 1 200 Economics and Finance ....................................................................... 5 300 History ................................................................................................ 6 400 Literature, Theater, and Writing .......................................................... 11 500 Languages ........................................................................................... 15 600 Religious Studies ................................................................................. 16 650 Humanities and Social Sciences ........................................................... 19 700 Current Events..................................................................................... 22 800 Science, Technology, and Health .......................................................... 23 900 Other Topics ........................................................................................ 27 Special Events Fall for the Book ........................................................................................ 31 Lectures ..................................................................................................... 32 RCC Professional Touring Artist Series ........................................................ 44 Performances and Trips ............................................................................ -

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

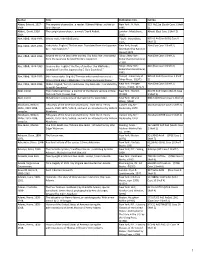

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel.