Analysis of the Bill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stapylton Final Version

1 THE PARLIAMENTARY PRIVILEGE OF FREEDOM FROM ARREST, 1603–1629 Keith A. T. Stapylton UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Page 2 DECLARATION I, Keith Anthony Thomas Stapylton, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed Page 3 ABSTRACT This thesis considers the English parliamentary privilege of freedom from arrest (and other legal processes), 1603-1629. Although it is under-represented in the historiography, the early Stuart Commons cherished this particular privilege as much as they valued freedom of speech. Previously one of the privileges requested from the monarch at the start of a parliament, by the seventeenth century freedom from arrest was increasingly claimed as an ‘ancient’, ‘undoubted’ right that secured the attendance of members, and safeguarded their honour, dignity, property, and ‘necessary’ servants. Uncertainty over the status and operation of the privilege was a major contemporary issue, and this prompted key questions for research. First, did ill definition of the constitutional relationship between the crown and its prerogatives, and parliament and its privileges, lead to tensions, increasingly polemical attitudes, and a questioning of the royal prerogative? Where did sovereignty now lie? Second, was it important to maximise the scope of the privilege, if parliament was to carry out its business properly? Did ad hoc management of individual privilege cases nevertheless have the cumulative effect of enhancing the authority and confidence of the Commons? Third, to what extent was the exploitation or abuse of privilege an unintended consequence of the strengthening of the Commons’ authority in matters of privilege? Such matters are not treated discretely, but are embedded within chapters that follow a thematic, broadly chronological approach. -

Explanatory Memorandum to the European Union

EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM TO THE EUROPEAN UNION (WITHDRAWAL) ACT 2018 (CONSEQUENTIAL MODIFICATIONS AND REPEALS AND REVOCATIONS) (EU EXIT) REGULATIONS 2018 2018 No. [XXXX] 1. Introduction 1.1 This explanatory memorandum has been prepared by the Department for Exiting the European Union and is laid before Parliament by Act. 1.2 This memorandum contains information for the Sifting Committees. 2. Purpose of the instrument 2.1 The purpose of this instrument is to ensure that the UK statute book accommodates “retained EU law”, a new body of domestic law introduced by the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (“the EUWA 2018”), coherently and effectively after the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. 2.2 This instrument amends the Interpretation Act 1978, the Interpretation and Legislative Reform (Scotland) Act 2010 (“the ILRA 2010”) and the Interpretation Act (Northern Ireland) 1954, which set out general rules of interpretation for legislation. 2.3 This instrument makes provision for how non-ambulatory cross-references to European Union legislation up to the point immediately before exit should be read. Non-ambulatory references are references which are not automatically updated.1 It also makes provision for how cross-references to EU legislation post-exit should be read. 2.4 It also adds a number of words and expressions to the ILRA 2010 and the Interpretation Act (Northern Ireland) 1954 and provides general rules of interpretation in light of the introduction of “retained EU law”. 2.5 These Regulations repeal and revoke primary and secondary legislations in consequence of the repeal of the European Communities Act 1972 (“the ECA 1972”) and arising from the withdrawal of the UK from the EU. -

Statutory Instrument Practice

Statutory Instrument Practice A guide to help you prepare and publish Statutory Instruments and understand the Parliamentary procedures relating to them - 5th edition (November 2017) Statutory Instrument Practice Page i Statutory Instrument Practice is published by The National Archives © Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to: [email protected]. Statutory Instrument Practice Page ii Preface This is the fifth edition of Statutory Instrument Practice (SIP) and replaces the edition published in November 2006. This edition has been prepared by the Legislation Services team at The National Archives. We will contact you regularly to make sure that this guide continues to meet your needs, and remains accurate. If you would like to suggest additional changes to us, please email them to the SI Registrar. Thank you to all of the contributors who helped us to update this edition. You can download SIP from: https://publishing.legislation.gov.uk/tools/uksi/si-drafting/si- practice. November 2017 Statutory Instrument Practice Page iii Contents PREFACE ............................................................................................................................. 3 CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................... 4 PART 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... -

Brexit: What Now? Uncoupling UK Law from the EU

Brexit: what now? Uncoupling UK law from the EU Much UK law is currently linked to that of the EU. Ending the UK’s membership of the EU will require significant uncoupling of the two legal systems. This paper provides an introduction to the inter-relationship of UK law and EU law and the legal mechanisms that might be used to separate them. As the issues surrounding implementation are highly complex, this introductory paper tries to provide a clear outline that can act as the foundation for more detailed analysis. The “ECA”: The European Communities Act 1972 – UK Membership – legal status the key UK statute implementing the UK’s UK law has historically taken the view that an membership of the EU. international treaty (or non-UK law ratified by the UK Government) does not form part of the domestic laws of the UK unless and until it is given effect by, or pursuant to, an Act of the UK Parliament. In limited circumstances, the UK Government can give effect to treaty obligations without specific legislation. The EU law perspective is that the obligations of EU law apply Categories of EU Law throughout the EU as an automatic consequence of EU law can be defined in the following membership of the EU. This means that EU law will, on principal categories: its own terms, no longer apply in the UK immediately after the UK stops being an EU Member State. As a – EU Treaties: The primary law of the EU. Binding result, the UK’s membership of the EU operates on on the UK as an EU Member State. -

When Interpretation Acts Require Interpretation ��3 Context Or Purpose As a Primary Factor to Be Considered When Divining Meaning Seems Unfathomable

2 UNSW Law Journal Volume 40(3) 3 WHEN INTERRETATION ACTS REUIRE INTERRETATION: UROSIVE STATUTORY INTERRETATION AND CRIMINAL LIABILITY IN UEENSLAND JAMES DUFFY AND JOHN O’BRIEN I INTRODUCTION When interpreting words or construing provisions1 in an Act of Parliament, the context in which the words appear and the purpose of the Act can be used to ascertain meaning. 2 The catchcry of text, context and purpose has become a repeated moniker for the High Court of Australia’s modern approach’ to statutory interpretation. 3 In this context, the thought of removing either text, BCom/LLB (Hons) (UQ), LLM (QUT), Lecturer, School of Law, Queensland University of Technology. Email: [email protected]. GradDipEd (Sec) (ACU), LLB (Hons) (Griffith), BCom (Hons) (Griffith), Associate Lecturer, School of Law, Queensland University of Technology. 1 The Acts Interpretation Act 1954 (Qld) sch 1 defines the word provision’ as follows: provision, in relation to an Act, means words or other matter that form or forms part of the Act, and includes (a) a chapter, part, division, subdivision, section, subsection, paragraph, subparagraph, sub-subparagraph, of the Act apart from a schedule or appendix of the Act and (b) a schedule or appendix of the Act or a section, subsection, paragraph, subparagraph, sub- subparagraph, item, column, table or form of or in a schedule or appendix of the Act and (c) the long title and any preamble to the Act. 2 CIC Insurance Ltd v Bankstown Football Club Ltd (1997) 187 CLR 384 (CIC Insurance’) Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority (1998) 194 CLR 355 (Project Blue Sky’) Alcan (NT) Alumina Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Territory Revenue (2009) 239 CLR 27 (Alcan’) Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Consolidated Media Holdings Ltd (2012) 250 CLR 503 (Consolidated Media Holdings’). -

1988 No 112 Imperial Laws Application

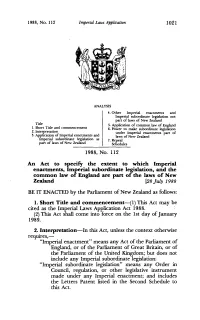

1988, No. 112 Imperial Laws Application 1021 ANALYSIS 4. Other Imperial enactments and Imperial subordinate legislation not part of laws of New Zealand Title 5. Application of common law of England 1. Short Title and commencement 6. Power to make subordinate legislation 2. InteTretation under Imperial enactments part of 3. Application of Imperial enactments and laws of New Zealand Imperial subordinate legislation as 7. Repeal part of laws of New Zealand Scliedules 1988, No. 112 An Act to specify the extent to which Imperial enactments, Imperial subordinate legislation, and the common law of England are part of the laws of New Zealand [28 July 1988 BE IT ENACTED by the Parliament of New Zealand as follows: I. Short Tide and commencement-(1) This Act may be cited as the Imperial Laws Application Act 1988. : (2) This Act shall come into force on the 1st day of January 1989. 2. Interpretation-In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires,- "Imperial enactment" means any Act of the Parliament of England, or of the Parliament of Great Britain, or of the Parliament of the United Kingdom; but does not include any Imperial subordinate legislation: "Imperial subordinate legislation" means any Order in Council, regulation, or other legislative instrument made under any Imperial enactment; and includes the Letters Patent listed in the Second Schedule to this Act. 1022 Imperial Laws Application 1988, No. 112 8. Application of Imperial enactrnents and Imperial subordinate legislation as part of laws of New Zealand- (1) The Imperial enactments listed in the First Schedule to this Act, and the Imperial subordinate legislation listed in the Second Schedule to this Act, are hereby declared to be part of the laws of New Zealand. -

Susan Crennan*

STATUTE LAW SOCIETY PAPER LONDON, 1 FEBRUARY 2010 STATUTES AND THE CONTEMPORARY SEARCH FOR MEANING SUSAN CRENNAN* Thank you very much for the invitation to speak to you tonight. It is frequently remarked both here and in Australia that much, if not most, of the law which applies today is based on statutes. Furthermore, in Australia, the principles to be applied to statutory interpretation are largely covered by various Acts Interpretation Acts. My topic tonight is the contemporary search for meaning exemplified in current approaches to statutory interpretation as seen from an Australian viewpoint. The contemporary search for meaning in the context of statutory interpretation occurs against a particular background. In recent decades there has been a good deal of reflection and writing by philosophers, linguists and literary theorists about text, meaning, context, certainty and uncertainty. Australian academic writers on statutory interpretation have noted these recent developments. ______________________ * Justice of the High Court of Australia - 1 - They have remarked on the relevance of the works of Foucault and Derrida, the influence of deconstruction in literary theory1 and the emergence of new interpretative theories including the dynamic theory of interpretation which holds that "the meaning of a statute is not fixed until it is applied to concrete circumstances, and it is neither uncommon nor illegitimate for the meaning of a provision to change over time".2 These broader intellectual developments have, I think, injected a certain vitality into recent debates over theories of statutory interpretation. However, whether that be so or not, it can be demonstrated that contemporary approaches to statutory interpretation preclude sacrificing meaning to inflexible theories or principles. -

INTERPRETATION ACT, 1960 (CA 4) As Amended by THE

INTERPRETATION ACT, 1960 (CA 4) As amended by THE INTERPRETATION (AMENDMENT) ACT, 1961 (ACT 92)1 THE INTERPRETATION (AMENDMENT) (NO.2) ACT, 1962 (ACT 145)2 INTERPRETATION ACT (AMENDMENT) LAW, 1982 (PNDCL 12)3 LOCAL ADMINISTRATION ACT, 1971 (ACT 359).4 LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 1993 (ACT 462).5 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Application. Operation of Enactments 2. Long title and preamble. 3. Punctuation. 4. Headings and marginal notes. 5. Descriptive words. 6. Amended, substituted and applied enactments. 6A. Authorisation of Reprinting. 6B. Validation of Certain Provious Reprints. 7. Textual insertion not affected by repeal of amending enactment. 8. Effect of repeal, revocation or cesser. 9. Effect of substituting enactment. Construction of Powers and Duties 10. Statutory powers and duties. 11. Power to grant licences, authorisations and permits. 12. Appointments to office. Procedure and Practice 13. Service of documents. 14. Rules of Court. 15. Administration of oath. 16. Deviation in forms. The Common Law and Customary Law 17. The common law. 18. Customary law. Interpretation of Enactments 19. Use of text-books and other publications in construction of enactments. 20. Republic: when bound. 21. Construction of statutory instrument. 22. Time. 23. Reckoning of periods of time by the calendar: month and year. 24. Distance. 25. Age. 26. Gender and number. 27. "Shall" and "may". 28. Corresponding parts of speech. 29. Reference to series of provisions. 30. Names commonly used. 31. Country. 32. Interpretation of particular terms. 32A. Extension of 1981-82 Financial Year 33. Commencement of this Act. 34. Repeals. AN ACT OF THE CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF GHANA ENTITLED THE INTERPRETATION ACT, 1960 AN ACT to provide for the interpretation of the Constitution and other enactments. -

Alice Through the Statutes

Alice Through the Statutes Marguerite E. Ritchie, Q.C.* "Definitions should not be too artificial. For example - 'dog' includes a cat is asking too much of the reader; 'animal' means a dog or a cat would be better." Memorandum on the Drafting of Acts of Parliament and Subordinate Legislation (1951), Department of Justice, Ottawa.] These words were used more than twenty years ago by a Canadian Government drafter of legislation. On the next page, the same author adopted without criticism or comment, a number of provisions from the federal InterpretationAct, 2 including the following: "[W]ords importing male persons include female persons and corporations."3 Dogs and cats have not objected to the way they are defined, and in fact have not taken any notice of the dictum with respect to them But women, demanding to be treated as humans, have protested constantly about the use of male terms to apply to both sexes. In * B.A., LL.B.(Alta), LL.M.(McGill), LL.D.(Alta), presently Vice-Chairman, Anti-dumping Tribunal, Ottawa. The author expresses appreciation to Lesley Mary M. Forrester of Trent University, Peterborough, for assistance in reviewing the statutes used in preparation of this article. 1 At 10. The Memorandum notes that it was prepared by Elmer A. Driedger, K.C., Parliamentary Counsel, Department of Justice. The Memorandum is hereinafter referred to as the Justice Drafting Memorandum. 2 R.S.C. 1927, c.1 as am. by S.C. 1947, c.64. 3 Justice Drafting Memorandum, 11, quoting s.31(1)(i) of the Interpretation Act, ibid. -

Originalist Sin: the Failure of Orginalism to Justify the Unitary

42513-lcb_24-3 Sheet No. 172 Side A 08/03/2020 09:57:48 LCB_24_3_Art_8_Mohan.docx (Do Not Delete) 7/14/20 10:41 PM NOTES & COMMENTS ORIGINALIST SIN: THE FAILURE OF ORIGINALISM TO JUSTIFY THE UNITARY EXECUTIVE THEORY by Marc Mohan* Originalists justify a “unitary executive” theory of presidential powers using the Con- stitution’s vesting of the executive power in “a President,” as opposed to a council or other multi-member setup. In spite of this justification’s popularity with originalists, a deeper understanding of prerogative and power, as the Founders understood those key concepts, reveals that the unitary executive theory cannot be justified through either the original intent or the original meaning of our founding document. In the absence of this grounding, the unitary executive theory is underpinned by modern exigencies and there- fore loses coherency as an originalist theory. I. Introduction .....................................................................................................1064 II. A Brief History of the Unitary Executive....................................................1066 III. Originalist Justifications for the Unitary Executive.....................1068 IV. The Evolution of the Royal Prerogative......................................................1069 V. Blackstone’s Taxonomy of the Royal Prerogative .....................................1071 A. Character ....................................................................................................1072 42513-lcb_24-3 Sheet No. 172 Side A 08/03/2020 09:57:48 -

Interpretation Act 1978, Cross Heading: Supplementary

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Interpretation Act 1978, Cross Heading: Supplementary. (See end of Document for details) Interpretation Act 1978 1978 CHAPTER 30 Supplementary 21 Interpretation etc. (1) In this Act “Act” includes a local and personal or private Act; and “subordinate legislation” means Orders in Council, orders, rules, regulations, schemes, warrants, byelaws and other instruments made or to be made under any Act [F1or made or to be made on or after [F2IP completion day under any retained direct EU legislation] other than retained direct EU CAP legislation as so defined][F3or made or to be made on or after exit day under retained direct EU CAP legislation as defined in section 2 of the Direct Payments to Farmers (Legislative Continuity) Act 2020]. (2) This Act binds the Crown. Textual Amendments F1 Words in s. 21(1) inserted (31.12.2020) by European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (c. 16), s. 25(4), Sch. 8 para. 19 (with s. 19, Sch. 7 para. 26, Sch. 8 para. 37) (as amended by S.I. 2020/463, regs. 1(1), 8); S.I. 2020/1622, reg. 3(n) F2 Words in s. 21(1) substituted (31.12.2020) by European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 (c. 1), s. 42(7), Sch. 5 para. 10 (with s. 38(3)) (as amended by S.I. 2020/463, regs. 1(1), 9); S.I. 2020/1622, reg. 5(j) F3 Words in s. 21(1) inserted (30.4.2020) by The Direct Payments to Farmers (Legislative Continuity) Act 2020 (Consequential Amendments) Regulations 2020 (S.I. -

Imperial Laws Application Bill-98-1

IMPERIAL LAWS APPLICATION BILL NOTE THIS Bill is being introduced in its present form so as to give notice of the legislation that it foreshadows to Parliament and to others whom it may concern, and to provide those who may be interested with an opportunity to make representations and suggestions in relation to the contemplated legislation at this early formative stage. It is not intended that the Bill should pass in its present form. Work towards completing and polishing the draft, and towards reviewing the Imperial enactments in force in New Zealand, is proceeding under the auspices of the Law Reform Council. It is intended to introduce a revised Bill in due course, and to allow ample time for study of the revised Bill and making representations thereon. The enactment of a definitive statutory list of Imperial subordinate legis- lation in force in New Zealand is contemplated. This list could appropriately be included in the revised Bill, but this course is not intended to be followed if it is likely to cause appreciable delay. Provision for the additional list can be made by a separate Bill. Representations in relation to the present Bill may be made in accordance with the normal practice to the Clerk of the Statutes Revision Committee of tlie House of Representatives. No. 98-1 Price $2.40 IMPERIAL LAWS APPLICATION BILL EXPLANATORY NOTE THIS Bill arises out of a review that is in process of being made by the Law Reform Council of the Imperial enactments in force in New Zealand. The intention is that in due course the present Bill will be allowed to lapse, and a complete revised Bill will be introduced to take its place.