The Battle for Battersea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LTN Winter 2021 Newsletter

THE LUTYENS TRUST To protect and promote the spirit and substance of the work of Sir Edwin Lutyens O.M. NEWSLETTER WINTER 2021 A REVIEW OF NEW BOOK ARTS & CRAFTS CHURCHES BY ALEC HAMILTON By Ashley Courtney It’s hard to believe this is the first book devoted to Arts and Crafts churches in the UK, but then perhaps a definition of these isn’t easy, making them hard to categorise? Alec Hamilton’s book, published by Lund Humphries – whose cover features a glorious image of St Andrew’s Church in Sunderland, of 1905 to 1907, designed by Albert Randall Wells and Edward Schroeder Prior – is split into two parts. The first, comprising an introduction and three chapters, attempts a definition, placing this genre in its architectural, social and religious contexts, circa 1900. The second, larger section divides the UK into 14 regions, and shows the best examples in each one; it also includes useful vignettes on artists and architects of importance. For the author, there is no hard- and-fast definition of an Arts and Crafts church, but he makes several attempts, including one that states: “It has to be built in or after 1884, the founding date of the Art Workers’ Guild”. He does get into a bit of a pickle, however, but bear with it as there is much to learn. For example, I did not know about the splintering of established religion, the Church of England, into a multitude of Nonconformist explorations. Added to that were the social missions whose goal was to improve the lot of the impoverished; here social space and church overlapped and adherents of the missions, such as CR Ashbee, taught Arts and Crafts skills. -

INVESTOR PACK INTERIM RESULTS for the 6 MONTHS ENDING 30TH JUNE 2018 INVESTOR PACK Introduction to Your Presenters

INVESTOR PACK INTERIM RESULTS FOR THE 6 MONTHS ENDING 30TH JUNE 2018 INVESTOR PACK Introduction to your presenters Mark Lawrence Group Chief Executive Officer Appointed to Board, 2nd May 2003 | Age 50 Mark has had 31 years with the company and started his career here by completing an electrical apprenticeship in 1987. He progressed through the company, becoming Technical Director in 1997, Executive Director in 2003 and Managing Director, London Operations in 2007. As Group Chief Executive Officer since January 2010, Mark has led strategic changes across the group and remains a hands-on leader, taking personal accountability and pride in Clarke's performance and, ultimately our shareholders’ and clients’ satisfaction. He regularly walks project sites and gets involved personally with many of our clients, contractors and our supply chain. Trevor Mitchell Group Finance Director Appointed to the Board on 1st February 2018 | Age 58 Trevor is a Chartered Accountant and accomplished finance professional with extensive experience across many sectors, including financial services, construction and maintenance, education and retail, working with organisations such as Balfour Beatty plc, Kier Group plc, Rok plc, Clerical Medical Group and Halifax plc. Prior to his appointment, Trevor had been working with TClarke since October 2016, assisting with simplifying the structure and improving the Group’s financial controls and procedures. 2 INVESTOR PACK M&E Contracting Every Picture tells a TClarke Story Secured Battersea Power Station Phase 2 Electrical -

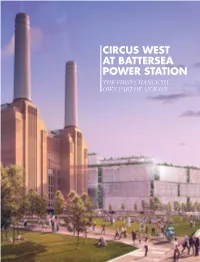

Circus West at Battersea Power Station the First Chance to Own Part of an Icon

CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION THE FIRST CHANCE TO OWN PART OF AN ICON PHASE 1 APARTMENTS 01 02 CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION 03 A GLOBAL ICON 04 AN IDEAL LOCATION 06 A PERFECT POSITION 12 A VISIONARY PLACE 14 SPACES IN WHICH PEOPLE WILL FLOURISH 16 AN EXCITING RANGE OF AMENITIES AND ACTIVITIES 18 CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION 20 RIVER, PARK OR ICON WHAT’S YOUR VIEW? 22 CIRCUS WEST TYPICAL APARTMENT PLANS AND SPECIFICATION 54 THE PLACEMAKERS PHASE 1 APARTMENTS 1 2 CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION A GLOBAL ICON IN CENTRAL LONDON Battersea Power Station is one of the landmarks. Shortly after its completion world’s most famous buildings and is and commissioning it was described by at the heart of Central London’s most the Observer newspaper as ‘One of the visionary and eagerly anticipated fi nest sights in London’. new development. The development that is now underway Built in the 1930s, and designed by one at Battersea Power Station will transform of Britain’s best 20th century architects, this great industrial monument into Battersea Power Station is one of the centrepiece of London’s greatest London’s most loved and recognisable destination development. PHASE 1 APARTMENTS 3 An ideal LOCATION LONDON The Power Station was sited very carefully a ten minute walk. Battersea Park and when it was built. It was needed close to Battersea Station are next door, providing the centre, but had to be right on the river. frequent rail access to Victoria Station. It was to be very accessible, but not part of London’s congestion. -

CIRCUS WEST VILLAGE – Designed by Drmm and Simpsonhaugh and Partners – BPSDC Office Headquarters – 865 New Homes – 23 Cafés, Restaurants and Shops

LIVE DON’T DO ORDINARY CGI of Battersea Power Station looking towards Battersea Park Battersea Power Station is a global icon, in one BATTERSEA POWER STATION of the world’s greatest cities. The Power Station’s incredible rebirth will see it transformed into one of the most exciting and innovative new neighbourhoods in the world, comprising unique homes designed YOUR HOME IN A by internationally renowned architects, set amidst the best shops, restaurants, offices, green space, GLOBAL ICON and spaces for the arts. 2 3 Battersea Power Station’s place in history is assured. From its very beginning, the building’s titanic form and scale THE ICON have captured the world’s imagination. Two design icons, one designer. The world-renowned London telephone box was one of architect Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s most memorable creations, the other was Battersea Power Station. Red buses, A BRITISH ICON Beefeaters, Buckingham Palace, Big Ben and Battersea Power Station – this icon takes its place as part of the world’s visual language for London. 4 5 BATTERSEA POWER STATION THE ICON A DESIGN ICON This was no ordinary Power Station, no ordinary design. Entering through bronze doors sculpted with personifications of power and energy, ascending via elaborate wrought iron staircases and arriving at the celebrated art deco control room with walls lined with Italian marble, polished parquet flooring and intricate glazed ceilings, looking out across the heart of the Power Station, its turbine hall, its giant walls of polished terracotta, it’s no wonder it was christened the ‘Temple of Modern Power’. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s design of Battersea Power Station turned this immense structure into a thing of beauty, which stood as London’s tallest building for 30 years and remains one of the largest brick buildings in the world. -

Camberwell Grove Conservation Area Appraisal Part 3

Camberwell Grove Conservation Area The Character and Appearance of the Area Figure 9 Regency streetscape at Grove Crescent – designated under the London Squares Preservation Act Figure 10 Brick paving and good modern lighting - St. Giles Churchyard Building types 3.1.12 The great majority of buildings in the Conservation Area are residential, particularly in Camberwell Grove and Grove Lane., the predominant type is three and four storey brick or stuccoed terraces of houses, dating from the late 18th/early 19th century and designed on classical principles, In other parts of the area there are two storey brick or stucco villas or pairs from the 19th century. Later, there are many examples of two storey brick houses built with arts and crafts/English revivalist influence, as at Grove Park, for example. 3.1.13 These residential building types provide the basis of the character of the Conservation area. Against their background a few institutional and public buildings are landmarks that stand out in the local context. On Denmark Hill, there is the main frontage of the Maudsley Hospital in early 20th century classical styles using red brick and Portland stone. Giles Gilbert Scott’s 1932 Salvation Army College employs a neo-classical style in dark brown brick. The Mary Datchelor School is in a Queen Anne revival style using red brick and plain tiled roofs, and St. Giles Church is an 1840s Gothic revival design. 3.2 Sub-area 1 - Lower Camberwell Grove St. Giles Church 3.2.1 St. Giles Church is a very important landmark in the Camberwell area, marking the "gateway" to the centre of Camberwell from the Peckham Road. -

ALBI CATHEDRAL and BRITISH CHURCH ARCHITECTURE TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:24 Am Page 2 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 Am Page 3

Albi F/C 24/1/2002 12:24 pm Page 1 and British Church Architecture John Thomas TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:24 am Page 1 ALBI CATHEDRAL AND BRITISH CHURCH ARCHITECTURE TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:24 am Page 2 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 3 ALBI CATHEDRAL and British Church Architecture 8 The in$uence of thirteenth-century church building in southern France and northern Spain upon ecclesiastical design in modern Britain 8 JOHN THOMAS THE ECCLESIOLOGICAL SOCIETY • 2002 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 4 For Adrian Yardley First published 2002 The Ecclesiological Society, c/o Society of Antiquaries of London, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1V 0HS www.ecclsoc.org ©JohnThomas All rights reserved Printed in the UK by Pennine Printing Services Ltd, Ripponden, West Yorkshire ISBN 0946823138 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 5 Contents List of figures vii Preface ix Albi Cathedral: design and purpose 1 Initial published accounts of Albi 9 Anewtypeoftownchurch 15 Half a century of cathedral design 23 Churches using diaphragm arches 42 Appendix Albi on the Norfolk coast? Some curious sketches by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott 51 Notes and references 63 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 6 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 7 Figures No. Subject Page 1, 2 Albi Cathedral, three recent views 2, 3 3AlbiCathedral,asillustratedin1829 4 4AlbiCathedralandGeronaCathedral,sections 5 5PlanofAlbiCathedral 6 6AlbiCathedral,apse 7 7Cordeliers’Church,Toulouse 10 8DominicanChurch,Ghent 11 9GeronaCathedral,planandinteriorview -

The Power Station

LIVE DON’T DO ORDINARY Battersea Power Station is a global icon, in one BATTERSEA POWER STATION of the world’s greatest cities. The Power Station’s incredible rebirth will see it transformed into one of the most exciting and innovative new neighbourhoods in the world, comprising unique homes designed YOUR HOME IN A by internationally renowned architects, set amidst the best shops, restaurants, offices, green space, GLOBAL ICON and spaces for the arts. 4 5 Battersea Power Station’s place in history is assured. From its very beginning, the building’s titan form and scale THE ICON has captured the world’s imagination. Two design icons, one designer. The world-renowned London telephone box was one of architect Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s most memorable creations, the other was Battersea Power Station. Red buses, A BRITISH ICON Beefeaters, Buckingham Palace, Big Ben and Battersea Power Station – this icon takes its place as part of the world’s visual language for London. 6 7 BATTERSEA POWER STATION THE ICON A DESIGN ICON This was no ordinary Power Station, no ordinary design. Entering through bronze doors sculpted with personifications of power and energy, ascending via elaborate wrought iron staircases and arriving at the celebrated art deco control room with walls lined with Italian marble, polished parquet flooring and intricate glazed ceilings, looking out across the heart of the Power Station, its turbine hall, its giant walls of polished terracotta, it’s no wonder it was christened the ‘Temple of Modern Power’. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s design of Battersea Power Station turned this immense structure into a thing of beauty, which stood as London’s tallest building for 30 years and remains one of the largest brick buildings in the world. -

Ekspan T-Mat Expansion Joint Installations

Head Office, UK & Export Sales Ekspan Limited Compass Works, 410 Brightside Lane, Sheffield S9 2SP Tel: +44 (0) 114 2611126 Fax: +44 (0) 114 2611165 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ekspan.com Ekspan T-Mat Expansion Joint Installations Case Studies Carriageway/Vehicular Traffic Specific Jacksons Port of Dover – 2017 Ekspan T-Mat 130 Expansion Joints installed at Port of Dover, during lane closures. Skanska St Ives Viaduct - 2017 Ekspan T-Mat 130 Expansion Joints installed on St Ives Viaduct, Cambridge, during full night closures. Registered in England: Registered Office: Compass Works, 410 Brightside Lane, Sheffield S9 2SP Co. Reg. 02564540 VAT Reg. 599-8691-41-000 BAM Nuttall Tower Bridge - 2016 Ekspan T-Mat 30 Expansion Joints installed on the Tower Bridge refurbishment Project, London. Skanska Battersea Power Station - 2016 Ekspan T-Mat 130 Expansion Joint installed on Halo Bridge - Batersea Power Station project, London. PJ Careys Selfridges London – 2015 Ekspan T-Mat 80 Expansion Joint and upstand installed at Selfridges, London. Registered in England: Registered Office: Compass Works, 410 Brightside Lane, Sheffield S9 2SP Co. Reg. 02564540 VAT Reg. 599-8691-41-000 SEGRO Heathrow X2 Hatton Cross – 2015 UnderEkspan Railway T-Mat 30 expansionBallast Specificjoint installed on X2 Hatton Cross, London Under Railway Ballast Specific Walsh Group Crum Creek, Philadelphia - 2016 Ekspan T-Mat 260 Expansion Joint installed on the Crum Creek Project, Philadelphia. Morgan Sindall A6 Hazel Grove Bridge - 2016 Ekspan T-Mat 130 Expansion Joint and upstand installed on A6 Hazel Grove Bridge, Stockport. Registered in England: Registered Office: Compass Works, 410 Brightside Lane, Sheffield S9 2SP Co. -

Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group

WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN Illustration credits and copyright references for photographs, maps and other illustrations are under negotiation with the following organisations: Dean and Chapter of Westminster Westminster School Parliamentary Estates Directorate Westminster City Council English Heritage Greater London Authority Simmons Aerofilms / Atkins Atkins / PLB / Barry Stow 2 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN The Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including St. Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site Management Plan Prepared on behalf of the Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group, by a consortium led by Atkins, with Barry Stow, conservation architect, and tourism specialists PLB Consulting Ltd. The full steering group chaired by English Heritage comprises representatives of: ICOMOS UK DCMS The Government Office for London The Dean and Chapter of Westminster The Parliamentary Estates Directorate Transport for London The Greater London Authority Westminster School Westminster City Council The London Borough of Lambeth The Royal Parks Agency The Church Commissioners Visit London 3 4 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE S I T E M ANAGEMENT PLAN FOREWORD by David Lammy MP, Minister for Culture I am delighted to present this Management Plan for the Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey and St Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site. For over a thousand years, Westminster has held a unique architectural, historic and symbolic significance where the history of church, monarchy, state and law are inexorably intertwined. As a group, the iconic buildings that form part of the World Heritage Site represent masterpieces of monumental architecture from medieval times on and which draw on the best of historic construction techniques and traditional craftsmanship. -

NICHOLAS TURNER PARTNER London

NICHOLAS TURNER PARTNER London Based in London, Nick is a real estate partner focussing on commercial property. +44 20 7466 +44 780 920 0665 2640 [email protected] linkedin.com/in/nick-turner-8777a513 KEY SERVICES KEY SECTORS Major Leasing Real Estate Real Estate Infrastructure EXPERIENCE Nick brings over two decades of experience to clients on all aspects of commercial property, including development and investment work. Nick has a particular focus on joint venture transactions and high-value mixed-use development work, including pre-letting and letting work for developers and tenants. Nick is focused on delivering strong commercial outcomes and has developed close relationships with many of the firm's key clients. Nick is the head of the firm’s 'corporate occupation' practice and he has been involved in some of the UK's largest high-value pre-letting transactions. Nick also focuses on the rail sector particularly on developments interacting wtith rail and underground assets. Nick's expertise in commercial property is highlighted by his recommendations in Chambers Global and Legal 500 UK. Nick's experience includes advising: Bluebutton Properties, a jv owning the Broadgate Estate in the City of London, on its major developments and pre-letting deals at 100 Liverpool Street, 135 Bishopsgate, 155 Bishopsgate and Broadwalk House. Tenants signed up include: SMBC, Millbanks, Bank of Montreal, Peel Hunt, TP ICap, McCann-Erickson, Eataly and Monzo Transport for London on its new head offices relocation to the International Quarter, Stratford, a development by a joint venture between Lend lease and LCR; the Northern Line Extension at Battersea Power Station; Crossrail overstation developments at Davies Street and Holborn and development agreements relating to Paddington, Holborn, London Bridge and Knightsbridge underground stations Canada Pension Plan Investment Board on its joint ventures and mixed-use developments with BT Pension Fund at Paradise Circus, Birmingham and Wellington Place, Leeds, both UK Canary Wharf Group on major lettings at one Canada Square. -

Pe1338 Wv Brochure-34.Pdf

Computer generated artist impression Take the next step in your London life and purchase a home at West View Battersea – a superb new collection of apartments, moments from Battersea Park, that offers you a peaceful and luxurious haven from the bustle of the city. On the doorstep of central London, West View Battersea at Berkeley's Vista Chelsea Bridge provides beautiful landscaped courtyards, luxurious interiors, and a building by world-leading architects Scott Brownrigg – all in one of the capital's most desirable riverside neighbourhoods. With Chelsea, Westminster and the iconic Battersea Power Station nearby, West View Battersea will open up a new chapter in urban living – in one of the greatest cities in the world. A NEW PERSPECTIVE Computer generated artist impression A NEW PANORAMA A new perspective to London-living 7 Computer generated artist impression 1 4 7 q West View Battersea River Thames Westminster The Shard 2 5 8 w Battersea Park Chelsea Bridge London Eye Canary Wharf 3 6 9 e Battersea Power Station Victoria Station The City Tate Britain 8 A NEW LANDSCAPE Be part of the evolution With evocative Victorian architecture, fashionable restaurants and bars, and one of the most renowned parks in London, Battersea is fast becoming an exclusive location. A rare corner of grandeur on the Thames, the area is well known for its iconic Battersea Power Station and stunning riverside views. With a wave of new investment in Nine Elms and a new Northern line Underground station, Battersea is also now one of the most sought-after areas in London. West View Battersea is a new part of Wandsworth’s story – an outstanding collection of properties that opens up the possibilities of city-living. -

YALE in LONDON – SUMMER 2013 British Studies 189 Churches: Christopher Wren to Basil Spence

YALE IN LONDON – SUMMER 2013 British Studies 189 Churches: Christopher Wren to Basil Spence THE CHURCHES OF LONDON: ARCHITECTURAL IMAGINATION AND ECCLESIASTICAL FORM Karla Britton Yale School of Architecture Email: [email protected] Class Time: Tuesday, Thursday 10-12:15 or as scheduled, Paul Mellon Center, or in situ Office Hours: By Appointment Yale-in-London Program, June 10-July 19, 2013 Course Description The historical trajectories of British architecture may be seen as inseparable from the evolution of London’s churches. From the grand visions of Wren through the surprising forms of Hawksmoor, Gibbs, Soane, Lutyens, Scott, Nash, and others, the ingenuity of these buildings, combined with their responsiveness to their urban environment, continue to intrigue architects today. Examining the ecclesiastical architecture of London beginning with Christopher Wren, this course critically addresses how prominent British architects sought to communicate the mythical and transcendent through structure and material, while also taking into account the nature of the site, a vision of the concept of the city, the church building’s relationship to social reform, ethics, and aesthetics. The course also examines how church architecture shaped British architectural thought in the work of historians such as Pevsner, Summerson, Rykwert, and Banham. The class will include numerous visits in situ in London, as well as trips to Canterbury, Liverpool, and Coventry. Taking full advantage of the sites of London, this seminar will address the significance of London churches for recent architects, urbanists, and scholars. ______________________________________________________________________________________ CLASS REQUIREMENTS Deliverables: Weekly reflection papers on the material covered in class and site visits. Full participation and discussion is required in classroom and on field trips.