Affordable Green: Renewing the Federal Commitment to Energy-Efficient, Healthy Housing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I HISTORIC WINDOWS and SUSTAINABILITY

HISTORIC WINDOWS AND SUSTAINABILITY: A COMPARISON OF HISTORIC AND REPLACEMENT WINDOWS BASED ON ENERGY EFFICIENCY, LIFE CYCLE ANALYSIS, EMBODIED ENERGY, AND DURABILITY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION BY ERIN CASEY WARE (WALTER GRONDZIK) BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2011 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank the members of my thesis committee, Walter Grondzik, William Hill, and David Kroll, for sharing their time and expertise. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements ii Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Defining Sustainability 16 Chapter 3: History of Windows 28 Chapter 4: Window Materials 40 Chapter 5: Windows and Energy 53 Chapter 6: Embodied Energy and Life Cycle Analysis 75 Chapter 7: Durability 85 Chapter 8: Findings 91 Appendix A National Park Service Technical Preservation Services Brief 9: The Repair of Historic Wooden Windows 97 Brief 13: The Repair and Thermal Upgrading of Historic Steel Windows 104 iii Appendix B Durability of Timber 116 Bibliography 117 iv Chapter 1 Introduction Historic preservation and environmentalism are often understood as unrelated or even opposing disciplines. Environmentalism is seen as dealing with the future while historic preservation is only concerned with the past. Popular perception is that only new buildings constructed using the latest green products are sustainable. Historic preservationists have long argued that historic buildings are inherently green because the energy required in their construction has already been expended. While this embodied energy is certainly a consideration, thorough research on whether historic buildings are sustainable in other ways has not been conducted. -

Green Retrofit of Existing Non-Domestic Buildings As a Multi Criteria Decision Making Process

Green retrofit of existing non-domestic buildings as a multi criteria decision making process by Jin Si Institute of Environmental Design and Engineering University College London Primary Supervisor: Dr Ljiljana Marjanovic-Halburd, IEDE Secondary Supervisor: Dr Sarah Bell, CEGE A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London 2017 Abstract With increased awareness of natural resources depletion, environmental pollution and social issues, the importance of sustainable development has been emphasised. Sustainable development is accepted as a guiding principle to reconcile economic development with limited natural resources and the dangers of environmental degradation. The building industry is a vital element of any economy and can have a significant impact on the environment. By virtue of the large size of existing buildings, green retrofit of existing buildings is an effective approach to improve building sustainability and energy performance. Unlike domestic building retrofit, bound in the research, non-domestic building retrofit lacks a sufficient research and requires a further investigation. Green retrofit of existing buildings is a complex decision making process. With the rise of sustainability agenda in the building sector, it is essential for decision makers to consider sustainability criteria, which address environmental, economic and social performance. Due to the intrinsic characteristic of existing buildings, technical challenges can emerge when integrating green technologies or measures. The qualitative and quantitative nature of these multiple criteria can increase the complexity of the decision making process. In addition, the decision making process may involve stakeholders from varying backgrounds. The conflicting perspectives can be the main barrier in the decision making of green retrofits. -

Climate Change, Buildings, and the Passive House Standard

Weathering the Storm: Climate Change, Buildings, and the Passive House Standard Jennifer Hogan, RRO, CET, Certified Passive House Consultant, LEED AP Pretium Engineering 4903 Thomas Alton Blvd., Suite 201, Burlington, ON L7M 0W8 Phone: 905-333-6550 • E-mail: [email protected] R C I I NTE R NAT I ONAL C ONVENT I ON AND T R ADE S HOW • M A rc H 14-19, 2019 H OGAN • 2 1 1 Abstract The climate data are clear: climate change is happening. As the severity and frequency of storms and other extreme weather events increase, it becomes more and more critical that we achieve the targets set out in the Paris Agreement. While limiting our global temperature rise to 2°C (3.6°F) may seem like an easy target, how we design, construct, and operate buildings will need to change dramatically. There are many sustainable building initiatives/programs, but Passive House is the most rigorous voluntary energy-based standard in the design and construction industry today. Passive House buildings: • Achieve up to a 90% reduction in energy required for space heating and cooling • Maintain a habitable interior temperature for weeks without power • Have excellent indoor environmental quality • Allow design flexibility Through the course of this paper, actual project examples will be used to reinforce each of the five key principles of the Passive House standard and how quality assurance is car- ried out for each: • Low U-value and continuous insulation • Continuous air barrier layer • Elimination of thermal bridges • Use of high-performance glazing • Optimization of mechanical ventilation with heat recovery We will conclude with a discussion on how the standard is being implemented in codes and standards at the local level using the Toronto Green Standard as an example, and dis- cuss the potential impact of widespread adoption of the standard. -

SUSTAINABILITY GUIDE for HISTORIC and OLDER HOMES Abigail Ahern PROJECT DESCRIPTION

CONCORD’S SUSTAINABILITY GUIDE FOR HISTORIC AND OLDER HOMES Abigail Ahern PROJECT DESCRIPTION The UNH Sustainability Institute Fellowship pairs students from across the United States with municipal, educational, corporate, and non-profit partners in New England to work on transformative sustainability initiatives each summer. Sustainability Fellows undertake challenging projects that are designed to create an immediate impact, offer a quality learning experience, and foster meaningful collaboration. Fellows work with their mentors at partner organizations during the summer, supported by a network of Fellows, partners, alumni, and the UNH Team. This summer, Abigail Ahern was chosen to work with the Town of Concord to develop a set of guidelines for historic homeowners interested in retrofitting their historic or older homes to become more sustainable. Concord has long been committed to sustainability and has a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050. About 30% of community wide greenhouse emissions in Concord come from residential homes. Achieving Concord’s 80% greenhouse gas reduction goal will require retrofitting the existing housing stock, much of which is located within an historic district or is subject to a Demolition Review bylaw, approximately 1,260 homes (14% of total buildings), to be more energy efficient and carbon-free. Retrofitting historic buildings located in a designated Historic District presents unique challenges because replacing inefficient windows and/or installing rooftop solar panels requires approval by the Historic Districts Commission (HDC) and may be of concern to members of the HDC when such work changes the look or character of the building. Additionally, owners of older houses that are subject to the Demolition Review bylaw may believe that retrofitting their home may be cost prohibitive or less efficient than tearing down and building new. -

Deep Energy Retrofits Market in the Greater Boston Area

DEEP ENERGY RETROFITS MARKET IN THE GREATER BOSTON AREA Commissioned by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency Final Report DEEP ENERGY RETROFITS MARKET IN THE GREATER BOSTON AREA Submitted: 13 October 2020 Prepared for: The Netherlands Innovation Network This report was commissioned by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency RVO. InnovationQuarter served as an advisor on the project. Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 II. Overview of Policy Drivers ........................................................................................................... 5 III. Economic Opportunity Assessment .............................................................................................. 9 IV. Market Snapshot ....................................................................................................................... 11 V. Actor Profiles ............................................................................................................................. 24 VI. Appendix ................................................................................................................................... 33 2 I. Introduction Cadmus is supporting the Netherlands Innovation Network (NIN) by providing an overview of the deep energy retrofit market in the Greater Boston Area. This report is intended to help Dutch companies in identify strategic opportunities to enter or expand their business opportunities in the Greater -

Business Case for Energy Efficient Building Retrofit and Renovation Table of Contents 4 Foreword: Making the Business Case

SmartMarket Report Business C a s e f o r EnergyEnergy EfficientEfficient Building Retrofit and Renovation Produced with support from Funding provided by U.S. Department of Energy through the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory ■ Design and Construction Intelligence SmartMarket Report McGraw-Hill Construction Business Case for Energy Effi cient Building President Retrofi t and Renovation Keith Fox SmartMarket Report Vice President, Product Development Executive Editor Kathryn E. Cassino Harvey M. Bernstein, F.ASCE, LEED AP About McGraw-Hill Construction Editorial Director McGraw-Hill Construction McGraw-Hill Construction (MHC), Research & Analytics/Alliances Michele A. Russo, LEED AP part of The McGraw-Hill Compa- Vice President, Industry Editors nies, connects people, projects and Enver Fitch, LEED Green Associate Insights & Alliances products across the design and con- Harvey M. Bernstein, F. ASCE, LEED AP Donna Laquidara-Carr, LEED AP struction industry, serving owners, Senior Director, Research & Analytics Senior Group Art Director architects, engineers, general con- Burleigh Morton Francesca Messina tractors, subcontractors, building Director, Partnerships & Alliances Contributing Art Director product manufacturers, suppliers, John Gudgel Donald Partyka dealers, distributors, and adjacent Director, Green Content & Production Manager markets. Research Communications Alison Lorenz A reliable and trusted source Michele A. Russo, LEED AP for more than a century, MHC has Contributing Editor David Sokol remained North America’s leading provider of construction project and Research Project Manager product information, plans and spec- Dana Gilmore, MRA, PRC ifi cations, industry news, market research, and industry trends and For further information on this SmartMarket Report or for any forecasts. In recent years, MHC has in the series, please contact emerged as an industry leader in the critical areas of sustainability and McGraw-Hill Construction Research & Analytics interoperability as well. -

Association of Residential Energy Efficiency Retrofits with Indoor Environmental Quality, Comfort, and Health: a Review of Empirical Data

Accepted manuscript: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107067 Association of Residential Energy Efficiency Retrofits with Indoor Environmental Quality, Comfort, and Health: A Review of Empirical Data William J. Fisk*, Brett C. Singer, Wanyu R. Chan Indoor Environment Group, 1 Cyclotron Rd. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA *corresponding author [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper reviews empirical data from evaluations of the influence of residential energy efficiency retrofits on indoor environmental quality conditions and self-reported thermal comfort and health. Data were extracted from 36 studies described in 44 papers plus two reports. Nearly all reviewed studies were performed in Europe or United States. Most studies evaluated retrofits of homes with low-income occupants. Indoor radon and formaldehyde concentrations tended to increase after retrofits that did not add whole-house mechanical ventilation. Study-average indoor concentrations of nitrogen dioxide and volatile organic compounds other than formaldehyde increased and decreased with approximately equal frequency. Average indoor temperatures during winter typically increased after retrofits, usually by less than 1.5 oC. Dampness and mold, usually based on occupant’s reports, almost always decreased after retrofits. Subjectively reported thermal comfort, thermal discomfort, non-asthma respiratory symptoms, general health, and mental health nearly always improved after retrofits. For asthma symptoms, the evidence of improvement slightly outweighed the evidence of worsening. There was insufficient evidence to determine whether changes in thermal comfort and health outcomes varied depending on the type of energy efficiency retrofit. The published research has numerous limitations including a lack of data from retrofits in warm-humid climates and minimal data on changes in objective health outcomes. -

Improving the Performance of Existing Commercial Buildings

Improving the Performance of Existing Commercial Buildings: The Chemistry of Sustainable Retrofits Improving the Performance of Existing Commercial Buildings: The Chemistry of Sustainable Retrofits | 3 Improving the Performance of Existing Commercial Buildings: The Chemistry of Sustainable Retrofits Table of contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.0 Economy, ecology and society—the impact of commercial buildings ......................................... 7 Economic Impacts and Opportunities .................................................................................................................... 7 Ecological Impacts and Opportunities ................................................................................................................... 8 Societal Impacts and Opportunities ....................................................................................................................... 9 2.0 Assessing the barriers and opportunities .................................................................................................11 3.0 Commercial building retrofit best practices ............................................................................................15 Low Effort, Low Cost Measures .............................................................................................................................. 1 5 Mid Effort, Moderate Investment Measures ......................................................................................................... -

Green Retrofit Survey and Analysis of Public Institution Building in Cold Region

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia Engineering 121 ( 2015 ) 1510 – 1514 9th International Symposium on Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (ISHVAC) and the 3rd International Conference on Building Energy and Environment (COBEE) Green Retrofit Survey and Analysis of Public Institution Building in Cold Region Huixing Li, Xiaoxu Cai, Guohui Feng, Shui Yu, Yibo Zhao , Yanhe Wang* School of Municipal and Environmental Engineering, Shenyang Jianzhu University, Shen-yang 110168, China Abstract According to " Twelfth Five-year "comprehensive energy conservation program of work" (Guo Fa [2011] No. 26) of the proposed objectives, in order to reduce the energy consumption of public institution existing buildings in cold region, public institutions existing buildings should be adapted to local conditions carried green retrofit. Taking Shenyang as the main object of study, green retrofit situation of five typical public sector buildings was mainly surveyed. Through the analysis of the survey data, combined with the evaluation index system of green building, this paper will propose the current problem of public institutions existing in the process of retrofit to determine the suitable technical measures. © 20152015 The The Authors. Authors.Published Published by Elsevier by Elsevier Ltd. This Ltd .is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (Peerhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/-review under responsibility of the organizing). committee of ISHVACCOBEE 2015. Peer-review under responsibility of the organizing committee of ISHVAC-COBEE 2015 Keywords: Public institutions; green retrofit; questionnaire; site visits; energy saving rate 1. Introduction Building energy consumption is 20% of the total energy consumption of the whole society. -

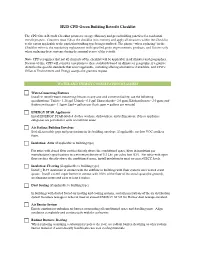

HUD CPD Green Building Retrofit Checklist

HUD CPD Green Building Retrofit Checklist The CPD Green Retrofit Checklist promotes energy efficiency and green building practices for residential retrofit projects. Grantees must follow the checklist in its entirety and apply all measures within the Checklist to the extent applicable to the particular building type being retrofitted. The phrase “when replacing” in the Checklist refers to the mandatory replacement with specified green improvements, products, and fixtures only when replacing those systems during the normal course of the retrofit. Note: CPD recognizes that not all elements of the checklist will be applicable in all climates and geographies. Because of this, CPD will consider exceptions to these standards based on climate or geography, if a grantee identifies the specific standards that aren’t applicable, including offering alternatives if available, and CPD’s Office of Environment and Energy accepts the grantees request. WATER AND ENERGY CONSERVATION MEASURES Water-Conserving Fixtures Install or retrofit water conserving fixtures in any unit and common facility, use the following specifications: Toilets-- 1.28 gpf; Urinals-- 0.5 gpf; Showerheads-- 2.0 gpm; Kitchen faucets-- 2.0 gpm; and Bathroom faucets-- 1.5gpm. [gpf = gallons per flush; gpm = gallons per minute] ENERGY STAR Appliances Install ENERGY STAR-labeled clothes washers, dishwashers, and refrigerators, if these appliance categories are provided in units or common areas. Air Sealing: Building Envelope Seal all accessible gaps and penetrations in the building envelope. If applicable, use low VOC caulk or foam. Insulation: Attic (if applicable to building type) For attics with closed floor cavities directly above the conditioned space, blow in insulation per manufacturer's specifications to a minimum density of 3.5 Lbs. -

White Paper Green Retrofitting 120609.Indd

Green Retrofi tti ng 101 © 2009 Strategic Sustainability Consulti ng Barbara Summers SUMMARY Th e green building label is not reserved for only new buildings; it is just as plausible to turn the millions of existing buildings into environmentally friendly structures. Green buildings are proven to reduce water and energy use and costs, create greater worker productivity and satisfaction, improved brand image, and better community relations. Renovations to a building include improving energy effi ciency, improving the heating and cooling system, creating a more sustainable site, improving water effi ciency, installing renewable energy, and using eco-friendly materials. Th ere are many projects that can be completed on a smaller budget, while others require a larger commitment. Even though there tends to be a high upfront cost, the average return on investment for a green retrofi t is two to fi ve years and there are substantial incentives that can reduce on the initial cost. Contents INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................1 APPEAL OF GREEN BUILDINGS .........................................................2 THE CHALLENGE OF RETROFITTING ..................................................3 BEFORE YOU RETROFIT ....................................................................4 THE RETROFIT PROCESS ...................................................................6 Energy Effi ciency ............................................................................... 6 Lighti ng ...................................................................................................6 -

MULTIFAMILY GREEN RETROFIT TOOLKIT Los Angeles Multifamily Hub TABLE of CONTENTS

MULTIFAMILY GREEN RETROFIT TOOLKIT Los Angeles Multifamily Hub TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from Kelly Boyer, LA Multifamily Director……………….…….3 Section 1: Why Go Green?.........................................................4-5 Section 2: HUD’s Green Mission…………………………………………….. 6-7 Section 3: Retrofit Resources………………………………………………....8-25 Section 4: Local Utility Rebates……………………………………………….26-33 Section 5: Get Green!.................................................................34-35 Section 6: Stay Green!................................................................36-39 There are many types of residential green retrofit tools to help lower energy costs, including foam insulation. Source: Flickr. 2 KELLY’S LETTER United States Department of Housing & Urban Development The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, also known as HUD, is a Cabinet department in the Executive branch of the United States federal government. It is currently administered by HUD Secretary, Shaun Donovan, and his staff. HUD is respon- sible for a variety or programs, including a number of grant and loan programs. Contact Information 3 1 WHY GO GREEN? Green retrofits allow multifamily property owners to improve energy efficiency in a way that is tailored to the building’s specific needs! WHAT IS GREEN RETROFITTING? Green retrofits are any changes, such as double pane windows, insulation or alter- native energy generation, that make a building or home more energy efficient. Green retrofits reduce a property’s energy and water usage, lower operational and maintenance costs, improve the residents’ quality of life, and reduce a building’s impact on the environment. DID YOU KNOW? Middle class families pay roughly 3.5% of their household income on utility costs. Low-income families spend approximately 20% on utility costs- and the costs are rising! The residential sector is responsible for 20% nation’s green house gas emis- sions.