I BEG to DIFFER: UNDERSTANDING DISAGREEMENT, AGREEMENT, and EMOTIONAL APPEALS in GUBERNATORIAL CAMPAIGN COMMUNICATION By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the 2016 Gubernatorial Elections by Jennifer M

GOVERNORS The National Mood and the Seats in Play: Understanding the 2016 Gubernatorial Elections By Jennifer M. Jensen and Thad Beyle With a national anti-establishment mood and 12 gubernatorial elections—eight in states with a Democrat as sitting governor—the Republicans were optimistic that they would strengthen their hand as they headed into the November elections. Republicans already held 31 governor- ships to the Democrats’ 18—Alaska Gov. Bill Walker is an Independent—and with about half the gubernatorial elections considered competitive, Republicans had the potential to increase their control to 36 governors’ mansions. For their part, Democrats had a realistic chance to convert only a couple of Republican governorships to their party. Given the party’s win-loss potential, Republicans were optimistic, in a good position. The Safe Races North Dakota Races in Delaware, North Dakota, Oregon, Utah Republican incumbent Jack Dalrymple announced and Washington were widely considered safe for he would not run for another term as governor, the incumbent party. opening the seat up for a competitive Republican primary. North Dakota Attorney General Wayne Delaware Stenehjem received his party’s endorsement at Popular Democratic incumbent Jack Markell was the Republican Party convention, but multimil- term-limited after fulfilling his second term in office. lionaire Doug Burgum challenged Stenehjem in Former Delaware Attorney General Beau Biden, the primary despite losing the party endorsement. eldest son of former Vice President Joe Biden, was Lifelong North Dakota resident Burgum had once considered a shoo-in to succeed Markell before founded a software company, Great Plains Soft- a 2014 recurrence of brain cancer led him to stay ware, that was eventually purchased by Microsoft out of the race. -

EAI Newsletter, August 2016 Printable Version

Ethan Allen Institute Newsletter – August 2016 (Printer Edition) Top Story: Help Us Warn Vermonters About the Carbon Tax We need to raise $10,000 for a media campaign that will get the facts out about the Carbon Tax. You know that a costly Carbon Tax on gasoline, diesel, home heating oil, propane, and natural gas will hurt Vermont’s families, businesses and our economy. When people find out that a Carbon Tax will add 88¢ to every gallon of gasoline and $1.02 to every gallon of home heating fuel, they overwhelmingly oppose the idea. Unfortunately, the left wing activist group VPIRG has sent over 50 “interns” door to door throughout the summer to mislead Vermonters into supporting what they call “Carbon Pricing” – no mention of how much the Carbon Tax will cost, or who will end up paying for it. Just the misleading claim that it will save the planet. We need to counter that propaganda with facts. And, this means we need to launch a paid media campaign that will educate Vermonters about the true nature of a statewide Carbon Tax. The Ethan Allen Institute has been a leading voice in Vermont warning our citizens about the proposed Carbon Tax and its inevitably harmful impacts on our state, if passed. Can we count on you to help us raise the $10,000 we need to launch a statewide radio and social media campaign? The next $5000 we receive for this effort will be matched, dollar for dollar, by a concerned contributor, so act now and double your impact! In January of 2015 The Ethan Allen Institute launched a statewide radio campaign alerting Vermonters to the fact that a Carbon Tax was on the table and what it meant for Vermont’s economic future. -

Health Wellness

Vermont's Race for Governor: Meet the Candidates — Page 12 MARCH 17 – APRIL 6, 2016 Amy Leventhal, Zenith Studios P Scott Barker, h o Tennis instructor t o s b y C a r l a health O c c a s wellness o Lindsay Davis Braun IN THIS ISSUE: Pg. 4 Sewage Overflow Issues A Quest to be Healthy and Love it by Carla Occaso ow can you be healthy and love it? and witnessing as you progress from longer least the idea of the hot tub and sauna. They Pg. 7 AroMed I’ll tell you when I find out. But times on the treadmill to heavier amounts of look so inviting. I haven’t done either of those in recent weeks I spent some time weight you can lift. And the loss of fat. And in years, either, though I used to do regular Aromatherapy Hgoing around to a couple of indoor fitness the defined muscles. Maybe it inspires and circuit training there in the 1990s. The Nau- facilities as well as checking out some of our invigorates you. I went to some local facilities tilus machines are still there, but also there is Pg. 10 Hands-On outdoor recreation attractions. And, though seeking just such inspiration. a weight room, a pool, tennis courts, a yoga I haven’t yet found something that sticks for studio and classes. Gardener I went for a fitness class at Zenith Studios on me, I had fun trying. Main Street in Montpelier. Loved the class. I got a thorough personal tour from the How many times have you contracted for a First of all, the trainer/owner, Amy Leventhal owner, Mike Woodfield. -

Appendix A: American Association for Public Opinion Research Transparency Initiative Details

Appendix A: American Association for Public Opinion Research Transparency Initiative Details 1. This project was sponsored by Vermont Public Radio (VPR), Colcester, VT. VPR suggested the topics and the overall study goals, while the Castleton Polling Institute developed the questionnaire. 2. Castleton Polling Institute (Rutland, Vermont) conducted the study on behalf of the sponsor. 3. The project was funded by Vermont Public Radio with support from the VPR Journalism Fund. 4. The questionnaire was fielded via telephone using live interviewers employed and trained by Castleton Polling Institute. The Institute employed CATI software for data gathering and sample management. Please see Appendix B for the questionnaire. 5. The population under study was Vermont residents age 18 and above. For estimates of the Vermont presidential general election contest, the Castleton Polling Institute used a likely voter model to estimate the voting population. 6. A dual frame landline and cell phone random digit dialing design was used; the sampling procedures for both frames are described below. All number, regardless of sample frame, were dialed manually; no auto dialing is employed. Cell-Phone sample For cell sample the numbers are generated from list of existing dedicated cell phone exchanges, the geographical information available for each number is limited to the area code (which places it in a State), the rate center name (which is the city/town where that phone exchange switching station resides), and billing address zip code where available. All cell phone calls were screened to be sure that the respondent lives in Vermont and that the respondent was 18 years of age or older. -

Survey Instrument

Appendix A: American Association for Public Opinion Research Transparency Initiative Details 1. This project was sponsored by Vermont Public Radio (VPR), Colcester, VT. VPR suggested the topics and the overall study goals, while the Castleton Polling Institute developed the questionnaire. 2. Castleton Polling Institute (Rutland, Vermont) conducted the study on behalf of the sponsor. 3. The project was funded by Vermont Public Radio. 4. The questionnaire was fielded via telephone using live interviewers employed and trained by Castleton Polling Institute. The Institute employed CATI software for data gathering and sample management. Please see Appendix B for the questionnaire. 5. The population under study was Vermont residents age 18 and above. For estimates of the Vermont presidential primary contests, the Castleton Polling Institute used a likely voter model to estimate the voting population. 6. A dual frame landline and cell phone random digit dialing design was used; the sampling procedures for both frames are described below. All number, regardless of sample frame, were dialed manually; no auto dialing is employed. Cell-Phone sample For cell sample the numbers are generated from list of existing dedicated cell phone exchanges, the geographical information available for each number is limited to the area code (which places it in a State), the rate center name (which is the city/town where that phone exchange switching station resides), and billing address zip code where available. All cell phone calls were screened to be sure that the respondent lives in Vermont and that the respondent was 18 years of age or older. The sample was acquired from Survey Sampling International, Shelton, Connecticut. -

Grafton Holds Forum for Candidates Regarding Vermont Energy Policies

VISIT US ON THE WEB AT VERMONTJOURNAL.COM Our website is new and improved, and it is user- and mobile-friendly! FREE REAL ECRWSS PRSRT STD GOLF US Postage ESTATE PAID NEWS Permit #90 White River Jct., VT on page 4B POSTAL CUSTOMER on page 2B Publishing for 55 Years! JULY 27, 2016 | WWW.VERMONTJOURNAL.COM VOLUME 55, ISSUE 9 Grafton holds forum for candidates regarding Vermont energy policies BY JENNIFER JONES Specifically, they discussed indus- area. torial candidate, suggested working The Shopper trial wind ridgeline development However, some were reluctant to with Canada, a country that utilizes projects and the role of the Vermont entirely write off the idea. low cost hydro-electric power. GRAFTON, Vt. - Gubernato- Public Service Board in renewable “If not here, then where?” asked When asked about the role of the rial candidates and elected officials energy projects. State Sen. Dick McCormack (D- Public Service Board in regulating came together recently in Grafton No participant stated that they Windsor), calling attention to the large energy development projects, to provide answers for concerned actively supported these projects, delicate balance between the in- gubernatorial candidates agreed the citizens regarding their thoughts on a matter that is forging a divide creasing need for renewable energy politics needed to be taken out of Vermont’s energy policies. amongst local communities in the sources in a state that treasures its the equation. unmatched aesthetic qualities. “The Public Service Board and McCormack said he sees a pos- the Public Service Department are sible solution to this quagmire in a allies of the utility companies,” said stricter permitting process and hav- Peter Galbraith, a Democratic gu- ing policies in place that regulate the bernatorial candidate. -

2016 Legislative Session Recap

FINAL LEGISLATIVE REPORT As the legislature has adjourned, this is KSE's last In This Issue legislative report for 2016. A special thanks to Marilyn Miller for her help and insights during the 2016 BIENNIUM ENDS session. Thanks also for having KSE serve as VADA's THE ISSUES lobbyist. We wish you all a great summer! VADA ISSUES BIENNIUM ENDS DMV FEE BILL The 2016 legislative session came to a close at 12:17 T-BILL AM on Saturday, May 7th, ending the second half of the CROSS-BORDER TAX biennium. Barring an unlikely veto session on June 9th, STUDY the 2015-16 General Assembly has concluded its work for the year. DRIVER'S LICENSE SUSPENSIONS The 2016 session was unique for many reasons, none EQUIPMENT DEALER more than the fact that the Democrats who have been "BILL OF RIGHTS" running the state for the last six years; namely, Governor Peter Shumlin, Senate President Pro-Tem John AUTOMATIC VOTER REGISTRATION Campbell and Speaker of the House Shap Smith are all retiring from their positions this year. STANDARD PROCEDURES FOR DEC PERMITS Because he announced last fall that he was not seeking re-election, Governor Shumlin's influence in the State ABOVEGROUND House was demonstrably weaker than it was six years STORAGE TANKS ago. The Governor's announcement also prompted a number of candidates to step forward hoping to replace him. On the Democratic side there is a three way primary race between former state senator Matt Dunne, former state senator Peter Galbraith, and Sue Minter, former transportation Secretary and, before that, state representative. -

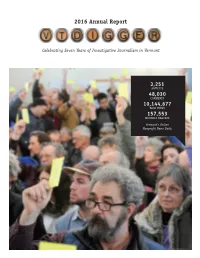

2016 Annual Report

2016 Annual Report Celebrating Seven Years of Investigative Journalism in Vermont 3,251 ARTICLES 48,030 COMMENTS 10,144,677 PAGE VIEWS 157,553 MONTHLY READERS Vermont’s Online Nonprofit News Daily WHO WE ARE VTDigger is a nonprofit online news daily dedicated to public service journalism. We cover Vermont politics, consumer affairs, business, education, energy, criminal justice and the environment. We also cover community government in four counties and Vermont’s congressional delegation in Washington, DC. VTDigger was founded in 2009 and merged with the Vermont Journalism Trust in 2011, becoming a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. The mission of the Vermont Journalism Trust and VTDigger is to produce rigorous journalism that explains complex issues, holds the government accountable to the public, and engages Vermonters in the democratic process. 2016 Board of Directors 2016 Staff and Interns Kevin Ellis, East Montpelier Executive Director & Editor: Anne Galloway Anne Galloway, East Hardwick Publisher: Diane Zeigler Lauren Geiger, Plainfield Associate Publisher: Phayvanh Luekhamhan Don Hooper, Brookfield Director of Underwriting: Theresa Murray-Clasen Tom Johnson, Poultney News Editor: Ruth Hare Curtis Ingham Koren, Brookfield Senior Editor and Reporter: Mark Johnson Crea Lintilhac, Shelburne Copy Editor: Cate Chant Neale Lunderville, Burlington Reporters: Jasper Craven, Mike Faher, Adam Bill Mares, Burlington Federman, Elizabeth Hewitt, Alan J. Keays, Erin David Mindich, Burlington Mansfield, Tiffany Danitz Pache, Mike Polhamus, Carol