Un-Locking the Processes and Practices of Informal Settlements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

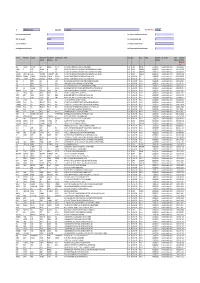

C1-27072018-Section

TATA CHEMICALS LIMITED LIST OF OUTSTANDING WARRANTS AS ON 27-08-2018. Sr. No. First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio / BENACC Amount 1 A RADHA LAXMI 106/1, THOMSAN RAOD, RAILWAY QTRS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI DELHI 110002 00C11204470000012140 242.00 2 A T SRIDHAR 248 VIKAS KUNJ VIKASPURI NEW DELHI 110018 0000000000C1A0123021 2,200.00 3 A N PAREEKH 28 GREATER KAILASH ENCLAVE-I NEW DELHI 110048 0000000000C1A0123702 1,628.00 4 A K THAPAR C/O THAPAR ISPAT LTD B-47 PHASE VII FOCAL POINT LUDHIANA NR CONTAINER FRT STN 141010 0000000000C1A0035110 1,760.00 5 A S OSAHAN 545 BASANT AVENUE AMRITSAR 143001 0000000000C1A0035260 1,210.00 6 A K AGARWAL P T C P LTD AISHBAGH LUCKNOW 226004 0000000000C1A0035071 1,760.00 7 A R BHANDARI 49 VIDYUT ABHIYANTA COLONY MALVIYA NAGAR JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302017 0000IN30001110438445 2,750.00 8 A Y SAWANT 20 SHIVNAGAR SOCIETY GHATLODIA AHMEDABAD 380061 0000000000C1A0054845 22.00 9 A ROSALIND MARITA 505, BHASKARA T.I.F.R.HSG.COMPLEX HOMI BHABHA ROAD BOMBAY 400005 0000000000C1A0035242 1,760.00 10 A G DESHPANDE 9/146, SHREE PARLESHWAR SOC., SHANHAJI RAJE MARG., VILE PARLE EAST, MUMBAI 400020 0000000000C1A0115029 550.00 11 A P PARAMESHWARAN 91/0086 21/276, TATA BLDG. SION EAST MUMBAI 400022 0000000000C1A0025898 15,136.00 12 A D KODLIKAR BLDG NO 58 R NO 1861 NEHRU NAGAR KURLA EAST MUMBAI 400024 0000000000C1A0112842 2,200.00 13 A RSEGU ALAUDEEN C 204 ASHISH TIRUPATI APTS B DESAI ROAD BOMBAY 400026 0000000000C1A0054466 3,520.00 14 A K DINESH 204 ST THOMAS SQUARE DIWANMAN NAVYUG NAGAR VASAI WEST MAHARASHTRA THANA -

Urban Biodiversity

NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY & ACTION PLAN – INDIA FOR MINISTRY OF ENVIRONEMENT & FORESTS, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA BY KALPAVRIKSH URBAN BIODIVERSITY By Prof. Ulhas Rane ‘Brindavan’, 227, Raj Mahal Vilas – II, First Main Road, Bangalore- 560094 Phone: 080 3417366, Telefax: 080 3417283 E-mail: < [email protected] >, < [email protected] > JANUARY 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Nos. I. INTRODUCTION 4 II. URBANISATION: 8 1. Urban evolution 2. Urban biodiversity 3. Exploding cities of the world 4. Indian scenario 5. Development / environment conflict 6. Status of a few large Urban Centres in India III. BIODIVERSITY – AN INDICATOR OF A HEALTHY URBAN ENVIRONMENT: 17 IV. URBAN PLANNING – A BRIEF LOOK: 21 1. Policy planning 2. Planning authorities 3. Statutory authorities 4. Role of planners 5. Role of voluntary and non-governmental organisations V. STRATEGIC PLANNING OF A ‘NEW’ CITY EVOLVING AROUND URBAN BIODIVERSITY: 24 1. Introduction 2. General planning norms 3. National / regional / local level strategy 4. Basic principles for policy planning 5. Basic norms for implementation 6. Guidelines from the urban biodiversity angle 7. Conclusion VI. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 35 2 VII. ANNEXURES: 36 Annexure – 1: The 25 largest cities in the year 2000 37 Annexure – 2: A megalopolis – Mumbai (Case study – I) 38 Annexure – 3: Growing metropolis – Bangalore (Case study – II) 49 Annexure – 4: Other metro cities of India (General case study – III) 63 Annexure – 5: List of Voluntary & Non governmental Organisations in Mumbai & Bangalore 68 VIII. REFERENCES 69 3 I. INTRODUCTION About 50% of the world’s population now resides in cities. However, this proportion is projected to rise to 61% in the next 30 years (UN 1997a). -

IAG Mumbai Programme

Mumbai Assembly, 8-12 February 2017 Hosted by ALMT Legal IAG’s first Assembly of 2017 will be held in Mumbai, India’s commercial heart and a fascinating city poised between Eastern and Western, old and new, cultures. The Assembly will be based at the iconic Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, on the edge of the Indian Ocean, in the centre of the city, right by the ‘Gateway to India’ monument. NB, Assembly dates, flights, extending the trip, booking deadline As at most IAG Assemblies, the formal Assembly events in Mumbai will start on the evening of Thursday 9th February 2017 (preceded by optional golf on Thursday morning). However those coming to Mumbai from the Americas or Europe will find that most flights arrive in the very late evening or soon after midnight. So you are strongly encouraged to arrive on the evening/ night of Wednesday 8th, so as not to miss anything! Some rooms have been reserved for Wednesday night for this. You are even more strongly encouraged to take the opportunity to extend your visit to India, and the point above may incline you towards doing so before the Assembly, although of course afterwards is also fine. The Taj group are offering discounted rates at their other hotels; please contact [email protected] for help on this. We can also put you in touch with travel agents for more general planning of your visit. Please note too that flights to Mumbai can become full, and flight costs can increase, earlier than on most other routes. It would therefore be advisable to investigate and book flights as soon as possible. -

MAHARERA REGISTRATION NUMBER: P51900015854 | Website

MAHARERA REGISTRATION NUMBER: P51900015854 | Website: https://maharera.mahaonline.gov.in/ Own the Address MAHARERA REGISTRATION NUMBER: P51900015854 | Website: https://maharera.mahaonline.gov.in/ Contents II. Location IV. Neighbourhood VI. Amenities & Lifestyle & Lifestyle V. Architecture III. Memorable & Design Views VII. Interiors I. Overview VIII. Team 16 58 30 50 10 64 24 42 An Address for Life 8 Artistic Impression Piramal Mahalaxmi – South Mumbai 9 I. The Quintessential Lifestyle, Elevated Overview 10 11 A location of choice, for the chosen few. Mumbai is one of the world’s most vibrant & eclectic cities. Its influence reaches far and wide. Once a group of seven islands, divided into precincts, it is now home to many of the country’s elite. 12 Overview Piramal Mahalaxmi – South Mumbai 13 Towering at 800 feet, rising above the South Mumbai skyline, Piramal Mahalaxmi elevates the quintessential Mumbai living with captivating views, and ease of connectivity, befitting the illustrious neighbourhood. Its sheer magnitude and enormity comprises of a breath-taking skyscraper with distinct amenities. Its design awakens profound interests. With memorable views and an unparalleled lifestyle, we guarantee you will fall in love. The South Tower shines as a new beacon, showcasing dramatic views of the Mahalaxmi Racecourse, the Arabian Sea and the city’s expansive Harbour. Piramal Mahalaxmi's emblem is inspired by the racetrack of the iconic Mahalaxmi Racecourse, that resides beside the property. Developed by the country’s premier developers, Piramal Realty & Omkar Realtors, the new development delivers architecture, lifestyle and legacy that only few will be privy to. Piramal Mahalaxmi, a premium luxury residential development, is located in one of Mumbai’s most desirable and sought-after addresses - Mahalaxmi. -

Sports Facilites

Locales in this category have hosted shoots of prominent films such as Kaminey, Jodhaa Akbar, Bombay Race Course, Khiladi, Khakee and Hero Award shows and concerts are also held regularly in two of the locales in this category Sports Facilities SPOTLIGHT 100 Scenic Locales in Maharashtra 209 ANDHERI SPORTS COMPLEX – MULTI-SPORTS FACILITY The Andheri Sports Complex is a multipurpose facility located on LOCATION FACT FILE PERMISSION AND FEE DETAILS Veera Desai Road in Andheri (West) in Mumbai. The complex has an ■ Andheri Sports Complex is in Mumbai Suburban district AUTHORITY Olympic-size swimming pool with four levels of diving and a modern which has an average high temperature of 38 degree Brihan Mumbai Kreeda Ani Lalitkala Pratishthan Celsius and a low of 18 degree Celsius. football stadium which played host to the Football Sports League. CONTACT DETAILS ■ Local transportation is easily available. The complex Complex In-charge It offers amazing infrastructure such as a cricket stadium, football is connected by rail (Andheri, Mumbai, 1 km; Mumbai Shahaji Raje Bhosale Kreeda Sankul stadium, swimming pool, badminton and squash courts, sports Central, 25 km) and air (Mumbai, 6.5 km). (Andheri Sports Complex), Jaiprakash Road Munshi Nagar, Andheri (West) training centre, multipurpose, gymnastic and lecture halls, ■ Nearby attractions include Mahakali Caves, Versova Beach, Mumbai, Maharashtra – 400058 auditoriums, open-air theatres and hostels with 28 fully Juhu Beach, ISKCON Temple, etc. Tel: +91-22-26744266/ 26744989/ 26743556/ 26740035 air-conditioned rooms and 28 non air-conditioned rooms. ■ Several luxury, star and budget category hotels are Web: www.bklp.mcgm.gov.in available across Mumbai. -

Mumbai Sight Seeing

Mumbai Sightseeing: Places of Interest GATEWAY OF INDIA The Gateway of India is the principal landmark of Mumbai. Built to commemorate the royal visit of George V and Queen Mary in 1911, construction was completed on the yellow basalt monument in 1924. The Gateway of India is analogous to Mumbai as the Statue of Liberty is to New York City. Across the street from the Taj Hotel Preferred time to visit: 06:00 to 21:00 GATEWAY OF INDIA MUMBAI UNIVERSITY BUILDING Set amidst beautifully laid lawns, the Mumbai University with its dreamy tableau of convocation hall, library and clock tower, reminds one of Oxford. It was designed in 1870 by architect Gilbert Scott, one of the few architects of international renown to design a building in colonial Mumbai. Situated at the gardens of the University building, the 260-foot Rajabai Clock tower rises above the portion of the library section, consisting of five elaborately decorated stories. 1.5km from the Taj Hotel Preferred time to visit: 09:00 to 17:30 MUMBAI MUNICIPAL CORPORATION The Mumbai Municipal Corporation Building is a 255-foot tall building in the Gothic style of architecture that was completed in 1893. The Municipal Corporation itself was created in 1865, with Arthur Crawford appointed as the first municipal commissioner of Mumbai for five years. 2.3km from the Taj Hotel Preferred time to visit: 09:00 to 17:30 MUMBAI MUNICIPAL CORP VICTORIA TERMINUS (CHATRPATI SHIVAJI TERMINUS) (C.S.T.) The Victoria Terminus, designed by F.W. Stevens follows the Italian Gothic style of architecture. -

Brochure Naresh.Cdr

SPACIOUS LIVING Site address: Lodha Aria, J. D. Road, Ram Tekadi, East Parel, Mumbai 400 015. www.lodhaaria.com E: [email protected] Corporate Office: Lodha Pavilion, Apollo Mills Compound, N. M. Joshi Marg, Mahalaxmi, Mumbai 400011, India. T: +91 22 6773 7373. F: +91 22 2300 0693. www.lodhagroup.com If space is the ultimate luxury in Mumbai, 30 residents are about to discover its true meaning. Welcome to Lodha Aria. Designed with just 2 residences per floor, Lodha Aria harks back to a time when the living was gracious, and ‘roomy interiors’ were de rigueur. Here, space abounds everywhere. The air-conditioned interiors come with room sizes surprisingly larger than you’re likely to find in today's apartments. While a rooftop club floor replete with swimming pool, air-conditioned gym and party zone, takes luxury to an altogether higher level. Conveniently located in East Parel, Lodha Aria is in the vicinity of the city’s burgeoning business and entertainment hub. Offering you the best of Mumbai, as well as the space and serenity of a private paradise. Best of all, you won't have to wait too long to take possession of your Lodha Aria residence. The home featured in the international interior magazine on your coffee table might well be yours. Living at Lodha Aria is a lofty experience. All elements, from views to layout, styling to finish, come together splendidly, in homes of rare distinction and class. Each air-conditioned residence is lavish in spread and commands panoramic sea views from the living room and master bedrooms. -

101 Places to Visit in Mumbai

25/12/2014 101 Places to Visit in Mumbai About.com About Travel India Travel . Mumbai Travel Guide Google Business Pages 101 PlaPlcacees iss no wt Googl eV My Biussiniests. G iet nyour Mumbai Yes, 101 Places tbou sViniseists! on Google today. By Sharell Cook India Travel Expert Share this Ads Bombay 101 Travel Market Luxury Travel Tourism Tourist Travel Guide India Historical Places India Travel Information Wondering what to do in Mumbai? Here's a list of 101 places to visit yes, 101 places! No Ads by Rubicon Project INDIA TRAVEL matter what your interest, you're sure to find something that appeals. If you want someone CATEGORIES to guide you, taking a Mumbai walking tour is a great way to explore the city. Many of Planning Your Trip to India Mumbai's attractions are in Colaba and the Fort district. Top Destinations in India Are 101 places too many? If you want to focus on the most popular ones, take a look at these Top 10 Mumbai Attractions. Visit them on one of these fascinating Mumbai Tours. Transport in India 20 Places to Visit in Where to Stay in India Mumbai -- Architecture What to See and Do in India Mumbai architecture is an eclectic blend of Gothic, Victorian, Art Deco, Indo Where to Eat and Drink in Saracenic and contemporary architectural India TODAY'S TOP 5 PICKS IN styles. Much of it remains from the TRAVEL colonial era of the British Raj. Nightlife in India Grant Faint/Photographer's Choice/Getty Images 1. Gateway of India 5 PicturesV oIfE IWnd MiaORE Designed to be the first thing that visitors see when approaching Mumbai by boat, Shopping in India the looming Gateway was completed in 1920. -

SIEMENS LIMITED List of Outstanding Warrants As on 18Th March, 2020 (Payment Date:- 14Th February, 2020) Sr No

SIEMENS LIMITED List of outstanding warrants as on 18th March, 2020 (Payment date:- 14th February, 2020) Sr No. First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A P RAJALAKSHMY A-6 VARUN I RAHEJA TOWNSHIP MALAD EAST MUMBAI 400097 A0004682 49.00 2 A RAJENDRAN B-4, KUMARAGURU FLATS 12, SIVAKAMIPURAM 4TH STREET, TIRUVANMIYUR CHENNAI 600041 1203690000017100 56.00 3 A G MANJULA 619 J II BLOCK RAJAJINAGAR BANGALORE 560010 A6000651 70.00 4 A GEORGE NO.35, SNEHA, 2ND CROSS, 2ND MAIN, CAMBRIDGE LAYOUT EXTENSION, ULSOOR, BANGALORE 560008 IN30023912036499 70.00 5 A GEORGE NO.263 MURPHY TOWN ULSOOR BANGALORE 560008 A6000604 70.00 6 A JAGADEESWARAN 37A TATABAD STREET NO 7 COIMBATORE COIMBATORE 641012 IN30108022118859 70.00 7 A PADMAJA G44 MADHURA NAGAR COLONY YOUSUFGUDA HYDERABAD 500037 A0005290 70.00 8 A RAJAGOPAL 260/4 10TH K M HOSUR ROAD BOMMANAHALLI BANGALORE 560068 A6000603 70.00 9 A G HARIKRISHNAN 'GOKULUM' 62 STJOHNS ROAD BANGALORE 560042 A6000410 140.00 10 A NARAYANASWAMY NO: 60 3RD CROSS CUBBON PET BANGALORE 560002 A6000582 140.00 11 A RAMESH KUMAR 10 VELLALAR STREET VALAYALKARA STREET KARUR 639001 IN30039413174239 140.00 12 A SUDHEENDHRA NO.68 5TH CROSS N.R.COLONY. BANGALORE 560019 A6000451 140.00 13 A THILAKACHAR NO.6275TH CROSS 1ST STAGE 2ND BLOCK BANASANKARI BANGALORE 560050 A6000418 140.00 14 A YUVARAJ # 18 5TH CROSS V G S LAYOUT EJIPURA BANGALORE 560047 A6000426 140.00 15 A KRISHNA MURTHY # 411 AMRUTH NAGAR ANDHRA MUNIAPPA LAYOUT CHELEKERE KALYAN NAGAR POST BANGALORE 560043 A6000358 210.00 16 A MANI NO 12 ANANDHI NILAYAM -

Piramal Mahalaxmi

Location Strategy All Rights Reserved. Piramal® 2018 Achievements & Success Story AN AIM TO TRANSFORM MUMBAI’S SKYLINE 1. Founded 2. Team 3. Development 4. Association with 5. Strategy 2012 250+ 15MN Sq.Ft. Global Experts Mumbai Focused 6. Up to 7. Up to 8. Received 9. Aspire to be one of 85% 15% Approx. US$434 million Residential Commercial - One of the largest India’s Most Admired Development Development private equity Real Estate investments in Indian real estate. Companies Board of Advisors THE WISDOM BEHIND THE SUCCESS Ajay Piramal Anand Piramal Nitin Nohria Chairman Founder Dean Piramal Group Piramal Realty Harvard Business School Robert Booth Deepak Parekh Ankur Sahu Managing Director Chairman CO Head MBD Asia Pacific Ellington Properties HDFC Goldman Sachs Partners GLOBAL PARTNERS TO BE PROUD ABOUT PerformanceDesigners & Consultants PartnersArchitects Construction Piramal Assurance OUR GREATEST ASSET First-of-its-kind initiative that assures a 100% buy-back guarantee. We offer to buy-back each customers’ purchased home at 95% of the existing market value, right until final possession. Current Projects OUR INSPIRED DEVELOPMENTS Thane Mulund Kurla Byculla Greater Mumbai N Mumbai MUMBAI – A DYNAMIC METROPOLIS – Mumbai ranks 42 on the Alpha Cities Index 2017 and scored a position of 39 out of 100. – Mumbai alone contributes to around 5% of India’s total GDP, in part because of its perceived position as the financial capital of India. Source: Wealth-X, Warburg-Barnes, 2017 Source: JLL, Mumbai - Hope on the Horizon - Offices 2020 Source: The Hindu - Ramesh Nair - 12 Jan 2018 Mumbai THE MOST PRESTIGIOUS ADDRESS – SOUTH MUMBAI South Mumbai being a high-end market serves as an ideal location for our Flagship project. -

CIN Company Name Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY)

CIN L99999MH1937PLC002726 Company Name MUKAND LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 12-AUG-2015 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of matured deposit 16072000 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number Investment Type Amount Proposed Date First Name Middle Name Name of Securities Due(in Rs. -

Heavy Showers Jam Traffic, Mumbaikars Can Expect Wet Sunday from Around the Web More from the Times of India

6/28/2016 Heavy showers jam traffic, Mumbaikars can expect wet Sunday Times of India Trichy Thiruvananthapuram Vadodara Varanasi Visakhapatnam Mumbai Crime Civic Issues Politics Schools & Colleges Events 1. News Home » 2. City » 3. Mumbai Heavy showers jam traffic, Mumbaikars can expect wet Sunday TNN | Jun 25, 2016, 10.14 PM IST HDFC™ Home Loan Online JEE 2016 Results Lowest Interest Rates of 9.40%*p.a. Lower EMI of NU Offers Scholarships Basis Your JEE Rank. just Rs.834/Lakh! Apply Now To Avail! homeloans.hdfc.com/EMI_Calculator nubtech.in/JEE Ads by Google Mumbai: The spell of heavy rainfall that began on Friday continued to lash the city and its surrounding areas on Saturday and threw traffic out of gear. The India Meteorological Department (IMD) has forecast that the heavy downpour will continue for the next 24 to 48 hours. From 8.30am to 5.30pm on Saturday, IMD recorded 95.8mm rainfall at the Colaba observatory and 34.6mm at Santacruz. The total rainfall recorded so far this season at the Colaba observatory is 266.5mm and at Santacruz 380.1mm. Navi Mumbai, too, got its share of the downpour; it recorded 215mm rainfall in the 24 hours from Friday. Thane got 97mm from Saturday midnight till 5pm. Weathermen have predicted heavy rainfall in parts of Konkan and Mumbai for the next 24 hours. "Mumbaikars can expect a wet Sunday. There is an offshore trough between south Gujarat and north Konkan, due to which parts of Maharashtra are getting very heavy rainfall," said K S Hosalikar, deputy director general, western region, IMD.