35 .R335 2017 | DDC 720/.470954792—Dc23 LC Record Available at Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copy of PAN Maharasthra Empanelled

MDINDIA HEALTH INSURANCE TPA PVT. LTD. Provider Management IN PAN Maharashtra Empanelled Hospital List Date : 05_10_2018 This has reference to captioned subject and inform you that the Cashless Facilities will only be available in PPN Hospitals (For Mumbai and Pune City), the list of the hospital is attached herewith. You are requested to kindly note of the same inform all Dy. CIROs so that they can avail this facility only in PPN Hospitals in case of Pune, Mumbai and other PPN Cities across India. Sr. No. Hospital Name Location City State Address Status PPN Hospital PPNCITY 1 Aashirwad Critical Care Unit And Multispeciality Hospital Mulund Mumbai Maharashtra Navinjyot , RRT Road, Mulund West Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 2 Aastha Health Care Mulund Mumbai Maharashtra Mulund Colony, Off LBS Rd, Opp Chheda Petrol Pump Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 3 Aastha Hospital Kandivali Mumbai Maharashtra 65, Balasinor Society, S.V.Road, Opp Fire Brigade, Kandivali W Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 4 Aayush Eye Clinic Chembur Mumbai Maharashtra 201/202, Coral Classic, 20th Road, Near Ambedkar Garden, ChemburEmpanelled IN PPN Mumbai 5 Abhishek Nursing Home Ghatkopar Mumbai Maharashtra Jagriti CHS, Nr Maratha Mandir Co-op Bank, Bhatwadi Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 6 Aditi Hospital Mulund Mumbai Maharashtra 185 - R, Alhad, P.K Road, Above Corporation Bank Mulund (W) Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 7 Aditi Hospital Malad Mumbai Maharashtra 1st Floor, Param Ratan, Opp. Post Office, Jakeria Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 8 Advanced Eye Hospital & Institute Sanpada Mumbai Maharashtra 30 the abbaires Sector 17 palm beach road sanpada Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 9 Aggarwal Eye Hospital Andheri Mumbai Maharashtra 102/5, Ketayun Mansion, Shahaji Raje Marg, Above T Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 10 Agrawal Eye Hospital Malad Mumbai Maharashtra 1st floor, maharaja apt, Malad (W), S V Road, opp. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Mumbai-Marooned.Pdf

Glossary AAI Airports Authority of India IFEJ International Federation of ACS Additional Chief Secretary Environmental Journalists AGNI Action for good Governance and IITM Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology Networking in India ILS Instrument Landing System AIR All India Radio IMD Indian Meteorological Department ALM Advanced Locality Management ISRO Indian Space Research Organisation ANM Auxiliary Nurse/Midwife KEM King Edward Memorial Hospital BCS Bombay Catholic Sabha MCGM/B Municipal Council of Greater Mumbai/ BEST Brihan Mumbai Electric Supply & Bombay Transport Undertaking. MCMT Mohalla Committee Movement Trust. BEAG Bombay Environmental Action Group MDMC Mumbai Disaster Management Committee BJP Bharatiya Janata Party MDMP Mumbai Disaster Management Plan BKC Bandra Kurla Complex. MoEF Ministry of Environment and Forests BMC Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation MHADA Maharashtra Housing and Area BNHS Bombay Natural History Society Development Authority BRIMSTOSWAD BrihanMumbai Storm MLA Member of Legislative Assembly Water Drain Project MMR Mumbai Metropolitan Region BWSL Bandra Worli Sea Link MMRDA Mumbai Metropolitan Region CAT Conservation Action Trust Development Authority CBD Central Business District. MbPT Mumbai Port Trust CBO Community Based Organizations MTNL Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd. CCC Concerned Citizens’ Commission MSDP Mumbai Sewerage Disposal Project CEHAT Centre for Enquiry into Health and MSEB Maharashtra State Electricity Board Allied Themes MSRDC Maharashtra State Road Development CG Coast Guard Corporation -

Thane District NSR & DIT Kits 15.10.2016

Thane district UID Aadhar Kit Information SNO EA District Taluka MCORP / BDO Operator-1 Operator_id Operator-1 Present address VLE VLE Name Name Name Mobile where machine Name Mobile number working (only For PEC) number 1 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO abha_akashS 7507463709 /9321285540 prithvi enterpriss defence colony ambernath east Akash Suraj Gupta 7507463709 Consultancy AMBARNATH thane 421502 Maharastra /9321285540 2 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO abha_abhisk 8689886830 At new newali Nalea near pundlile Abhishek Sharma 8689886830 Consultancy AMBARNATH Maharastraatre school, post-mangrul, Telulea, Ambernath. Thane,Maharastra-421502 3 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO abha_sashyam 9158422335 Plot No.901 Trivevi bhavan, Defence Colony near Rakesh Sashyam GUPta 9158422335 Consultancy AMBARNATH Ayyappa temple, Ambernath, Thane, Maharastra- 421502 4 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO abha_pandey 9820270413 Agrawal Travels NL/11/02, sector-11 ear Sandeep Pandey 9820270413 Consultancy AMBARNATH Ambamata mumbai, Thane,Maharastra-400706 5 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO pahal_abhs 8689886830 Shree swami samath Entreprises nevalinaka, Abhishek Sharma 8689886830 Consultancy AMBARNATH mangrul, Ambarnath, Thane,Maharastra-421301 6 Vakrangee LTD Thane Ambarnath BDO VLE_MH610_NS055808 9637755100/8422883379 Shop No.1, Behind Datta Mandir Durga Devi Pada Priyanka Wadekar 9637755100/ AMBARNATH /VLE_MCR610_NS073201 Old Ambernath, East 421501 8422883379 7 Vakrangee LTD Thane Ambarnath BDO VLE_MH610_NS076230 9324034090 / Aries Apt. Shop No. 3, Behind Bethel Church, Prashant Shamrao Patil 9324034090 / AMBARNATH 8693023777 Panvelkar Campus Road, Ambernath West, 8693023777 421505 8 Vakrangee LTD Thane Ambarnath BDO VLE_MH610_NS086671 9960261090 Shop No. 32, Building No. 1/E, Matoshree Nagar, Babu Narsappa Boske 9960261090 AMBARNATH Ambarnath West - 421501 9 Vakrangee LTD Thane Ambarnath BDO VLE_MH610_NS037707 9702186854 House No. -

C1-27072018-Section

TATA CHEMICALS LIMITED LIST OF OUTSTANDING WARRANTS AS ON 27-08-2018. Sr. No. First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio / BENACC Amount 1 A RADHA LAXMI 106/1, THOMSAN RAOD, RAILWAY QTRS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI DELHI 110002 00C11204470000012140 242.00 2 A T SRIDHAR 248 VIKAS KUNJ VIKASPURI NEW DELHI 110018 0000000000C1A0123021 2,200.00 3 A N PAREEKH 28 GREATER KAILASH ENCLAVE-I NEW DELHI 110048 0000000000C1A0123702 1,628.00 4 A K THAPAR C/O THAPAR ISPAT LTD B-47 PHASE VII FOCAL POINT LUDHIANA NR CONTAINER FRT STN 141010 0000000000C1A0035110 1,760.00 5 A S OSAHAN 545 BASANT AVENUE AMRITSAR 143001 0000000000C1A0035260 1,210.00 6 A K AGARWAL P T C P LTD AISHBAGH LUCKNOW 226004 0000000000C1A0035071 1,760.00 7 A R BHANDARI 49 VIDYUT ABHIYANTA COLONY MALVIYA NAGAR JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302017 0000IN30001110438445 2,750.00 8 A Y SAWANT 20 SHIVNAGAR SOCIETY GHATLODIA AHMEDABAD 380061 0000000000C1A0054845 22.00 9 A ROSALIND MARITA 505, BHASKARA T.I.F.R.HSG.COMPLEX HOMI BHABHA ROAD BOMBAY 400005 0000000000C1A0035242 1,760.00 10 A G DESHPANDE 9/146, SHREE PARLESHWAR SOC., SHANHAJI RAJE MARG., VILE PARLE EAST, MUMBAI 400020 0000000000C1A0115029 550.00 11 A P PARAMESHWARAN 91/0086 21/276, TATA BLDG. SION EAST MUMBAI 400022 0000000000C1A0025898 15,136.00 12 A D KODLIKAR BLDG NO 58 R NO 1861 NEHRU NAGAR KURLA EAST MUMBAI 400024 0000000000C1A0112842 2,200.00 13 A RSEGU ALAUDEEN C 204 ASHISH TIRUPATI APTS B DESAI ROAD BOMBAY 400026 0000000000C1A0054466 3,520.00 14 A K DINESH 204 ST THOMAS SQUARE DIWANMAN NAVYUG NAGAR VASAI WEST MAHARASHTRA THANA -

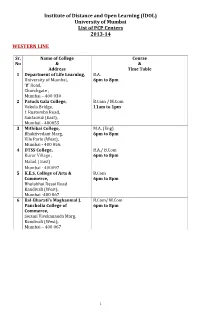

University of Mumbai List of PCP Centers 2013-14 WESTERN LINE

Institute of Distance and Open Learning (IDOL) University of Mumbai List of PCP Centers 201314 WESTERN LINE Sr. Name of College Course No & & Address Time Table 1 Department of Life Learning, B.A. University of Mumbai, 6pm to 8pm ‘B’ Road, Churchgate , Mumbai – 400 030 2 Patuck Gala College, B.Com / M.Com Vakola Bridge, 11am to 1pm 1 Rustomba Road, Santacruz (East), Mumbai ‐ 400055 3 Mithibai College, M.A. (Eng) Bhaktivedant Marg, 6pm to 8pm Vile Parle (West), Mumbai ‐ 400 056. 4 DTSS College, B.A./ B.Com Kurar Village , 6pm to 8pm Malad ( East) Mumbai ‐ 400097 5 K.E.S. College of Arts & B.Com Commerce, 6pm to 8pm Bhulabhai Desai Road Kandivali (West), Mumbai ‐400 067 6 BalBharati’s Maghanmal J. B.Com/ M.Com Pancholia College of 6pm to 8pm Commerce, Swami Vivekananda Marg, Kandivali (West), Mumbai – 400 067 1 CENTRAL LINE 1 S. K. Somaiya College of Sci & B.A./B.Com / M.A. /M.Com Com. Monday to Saturday: 4pm to 8pm Vidyanagar, Sunday: 8 am to 9pm Vidyavihar, Mumbai – 400 077. 2 Acharya Marathe College, B.A. / B.Com N.G. Acharya Marg 6pm to 8pm Chembur Mumbai ‐ 400071 3 Asmita College, BA/ B.com Om Vidyalankar Shikshan M.A. (Eco/History) Sansthas Asmita College of Law M.Com (Management/Accounting) Kannamwar nagar 2, Saturday :4.30pm to 8.30pm Vikhroli (East) Sunday : 7.30am to 1.30pm Mumbai ‐ 400083 4 M.S College, B.Com/B.A/ M.A Habib Educational Complex, 6pm to 8pm Behind Kader Palace, Kausa, M H Mohini Road, Mumbra, Thane ‐ 400612 5 R. -

Urban Biodiversity

NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY & ACTION PLAN – INDIA FOR MINISTRY OF ENVIRONEMENT & FORESTS, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA BY KALPAVRIKSH URBAN BIODIVERSITY By Prof. Ulhas Rane ‘Brindavan’, 227, Raj Mahal Vilas – II, First Main Road, Bangalore- 560094 Phone: 080 3417366, Telefax: 080 3417283 E-mail: < [email protected] >, < [email protected] > JANUARY 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Nos. I. INTRODUCTION 4 II. URBANISATION: 8 1. Urban evolution 2. Urban biodiversity 3. Exploding cities of the world 4. Indian scenario 5. Development / environment conflict 6. Status of a few large Urban Centres in India III. BIODIVERSITY – AN INDICATOR OF A HEALTHY URBAN ENVIRONMENT: 17 IV. URBAN PLANNING – A BRIEF LOOK: 21 1. Policy planning 2. Planning authorities 3. Statutory authorities 4. Role of planners 5. Role of voluntary and non-governmental organisations V. STRATEGIC PLANNING OF A ‘NEW’ CITY EVOLVING AROUND URBAN BIODIVERSITY: 24 1. Introduction 2. General planning norms 3. National / regional / local level strategy 4. Basic principles for policy planning 5. Basic norms for implementation 6. Guidelines from the urban biodiversity angle 7. Conclusion VI. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 35 2 VII. ANNEXURES: 36 Annexure – 1: The 25 largest cities in the year 2000 37 Annexure – 2: A megalopolis – Mumbai (Case study – I) 38 Annexure – 3: Growing metropolis – Bangalore (Case study – II) 49 Annexure – 4: Other metro cities of India (General case study – III) 63 Annexure – 5: List of Voluntary & Non governmental Organisations in Mumbai & Bangalore 68 VIII. REFERENCES 69 3 I. INTRODUCTION About 50% of the world’s population now resides in cities. However, this proportion is projected to rise to 61% in the next 30 years (UN 1997a). -

Unpaid Warrants 23 10 2015

Cheque No Warrant No Warrant Date Folio No Amount Beneficiary Name ADD1 ADD2 ADD3 City PIN 563 3 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000003369 160.00 MAJOR KANWALJIT SINGH SANDHU HOUSE NO 2088/3 SECTOR 45-C CHANDIGARH160047 160047 564 4 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000003468 80.00 BINAY GARODIA C/O DIAMOND STORES H S ROAD DIBRUGARH ASSAM1 565 5 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000002680 400.00 MUKESH AGGARWAL C 41 RAJOURI GARDEN N.DELHI 0 569 9 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000002190 80.00 SHARDA JAISWAL QR NO 6-C 25 OBRA COLONY PO OBRA DIST SONEBHADRA U P0 571 11 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000002616 400.00 RASHMI M JAIN C/O NAKODA WIRE INDUSTRIES 143 NEAR SATAKHEDI MHOW NEEMUCH ROAD RATLAM M P0 573 13 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000005104 1,040.00 PRATOSH PRASAD F-301 KUKREJA ESTATE SECTOR 11 CBD BELAPUR NEW MUMBAI 574 14 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000004244 240.00 ARSHIA IMTIAZ CHIKTE B 2 SHAMIN APMT ALMAS COLONY ROAD BLOCK 13 IST FLR KAUSA MUMBRA DIST THANE0 575 15 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000005244 240.00 HEMANT LODHA 65 MALDAS STREET 0 UDAIPUR 576 16 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000004827 240.00 HEM LATA BOTHRA RAJ CLOTH STORE LOOKARASUR BIHAR 577 17 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000004148 80.00 SANJEEV KUMAR SAXENA C-131 SECTOR H ALIGANJ LUCKNOW0 578 18 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000004154 80.00 MEETA PRAFUL SHAH 7 PARMESHWAR KRUPA TILAK ROAD GHATKOPAR0 579 19 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000003325 560.00 GOPALKRISHNA K HEGDE BLDG NO 18 FLAT NO 1847 VANARAIE COLONYMAHADA WESTERN EXPRESSHIGHWAY GOREGAON E BOMBAY440065 440065 580 20 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000003881 240.00 JYOTSANA P SOLANKI PVT PLOT NO :962/1 SECTOR NO 2 CORNER C GANDHI NAGAR GUJARAT382002 382002 581 21 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000002358 160.00 QURESH F WADHAWALA C/O FAZAL MANZIL ATHWADA BAZAR BHUSAVAL M S0 582 22 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000002837 160.00 ROLI SRIVASTAVA 258/19 NEW BASTI SOHBATIABAG ALLAHABAD UP0 583 23 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000002470 80.00 SHASHI PANT OR 97/3/5 B B H E L HARDWAR 0 585 25 24-Jul-2015 00000000000000002101 80.00 MAMTA AGRAWAL M-203,MANOJ VIHAR INDIRA PURAM GHAZIABADU.P. -

IAG Mumbai Programme

Mumbai Assembly, 8-12 February 2017 Hosted by ALMT Legal IAG’s first Assembly of 2017 will be held in Mumbai, India’s commercial heart and a fascinating city poised between Eastern and Western, old and new, cultures. The Assembly will be based at the iconic Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, on the edge of the Indian Ocean, in the centre of the city, right by the ‘Gateway to India’ monument. NB, Assembly dates, flights, extending the trip, booking deadline As at most IAG Assemblies, the formal Assembly events in Mumbai will start on the evening of Thursday 9th February 2017 (preceded by optional golf on Thursday morning). However those coming to Mumbai from the Americas or Europe will find that most flights arrive in the very late evening or soon after midnight. So you are strongly encouraged to arrive on the evening/ night of Wednesday 8th, so as not to miss anything! Some rooms have been reserved for Wednesday night for this. You are even more strongly encouraged to take the opportunity to extend your visit to India, and the point above may incline you towards doing so before the Assembly, although of course afterwards is also fine. The Taj group are offering discounted rates at their other hotels; please contact [email protected] for help on this. We can also put you in touch with travel agents for more general planning of your visit. Please note too that flights to Mumbai can become full, and flight costs can increase, earlier than on most other routes. It would therefore be advisable to investigate and book flights as soon as possible. -

MAHARERA REGISTRATION NUMBER: P51900015854 | Website

MAHARERA REGISTRATION NUMBER: P51900015854 | Website: https://maharera.mahaonline.gov.in/ Own the Address MAHARERA REGISTRATION NUMBER: P51900015854 | Website: https://maharera.mahaonline.gov.in/ Contents II. Location IV. Neighbourhood VI. Amenities & Lifestyle & Lifestyle V. Architecture III. Memorable & Design Views VII. Interiors I. Overview VIII. Team 16 58 30 50 10 64 24 42 An Address for Life 8 Artistic Impression Piramal Mahalaxmi – South Mumbai 9 I. The Quintessential Lifestyle, Elevated Overview 10 11 A location of choice, for the chosen few. Mumbai is one of the world’s most vibrant & eclectic cities. Its influence reaches far and wide. Once a group of seven islands, divided into precincts, it is now home to many of the country’s elite. 12 Overview Piramal Mahalaxmi – South Mumbai 13 Towering at 800 feet, rising above the South Mumbai skyline, Piramal Mahalaxmi elevates the quintessential Mumbai living with captivating views, and ease of connectivity, befitting the illustrious neighbourhood. Its sheer magnitude and enormity comprises of a breath-taking skyscraper with distinct amenities. Its design awakens profound interests. With memorable views and an unparalleled lifestyle, we guarantee you will fall in love. The South Tower shines as a new beacon, showcasing dramatic views of the Mahalaxmi Racecourse, the Arabian Sea and the city’s expansive Harbour. Piramal Mahalaxmi's emblem is inspired by the racetrack of the iconic Mahalaxmi Racecourse, that resides beside the property. Developed by the country’s premier developers, Piramal Realty & Omkar Realtors, the new development delivers architecture, lifestyle and legacy that only few will be privy to. Piramal Mahalaxmi, a premium luxury residential development, is located in one of Mumbai’s most desirable and sought-after addresses - Mahalaxmi. -

![Jul-Sep 2016] N Line with General Lack of Activity in the the Worst Performer Was the North Region, 2016 Quarter, As Three Years Ago](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9920/jul-sep-2016-n-line-with-general-lack-of-activity-in-the-the-worst-performer-was-the-north-region-2016-quarter-as-three-years-ago-1779920.webp)

Jul-Sep 2016] N Line with General Lack of Activity in the the Worst Performer Was the North Region, 2016 Quarter, As Three Years Ago

FOREWORD Mild tapering of inflation and a normal monsoon finally paved the way for lowering of REPO rate by 25 basis points, taking it to its lowest level in the last 5 years. The continued fall in both imports and exports, coupled with tepid investment demand has led RBI to pass on the cut. The Y-o-Y GDP growth rate also slowed down from 7.9% in the JFM quarter to 7.1% this quarter. The expected rise in oil prices from next year is also a major concern for the economy, which imports most of the oil it needs. High NPAs in the banking sector and construction delays in infrastructure and real estate also remain as major concerns. However, the economy remains strong despite headwinds facing the world economy and geopolitical turmoil across Asia and Europe. The Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) is still above 52 level and GDP growth forecasts till 2020 by various multilateral agencies, remain above 7%. The lowering of Repo rate is expected to bring down both project finance as well as home loan costs, lowering the overall cost of buying a house. The inevitable implementation of Real Estate Regulation and Development (RERA) Act, 2016 has led developers to hasten the delivery of their projects. This trend was clearly evident in the quarterly average prices data of Under Construction (UC) vs Ready-to- Move-in (RM) stock, where the premium commanded by RM properties came down due to increase in RM stock, as a portion of UC projects were delivered over the quarter. RERA is a step in the right direction but will bear fruit only in 2-3 years, and till then the Indian real estate sector remains in turbulent waters, and its health can only be gauged through inferential means like pricing and inflation in the sector. -

Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards: Deluge in Mumbai on 26/7

Mumbai after 26/7 Deluge: Some Issues and Concerns in Regional Planning R. B. Bhagat1, Mohua Guha2 and Aparajita Chattopadhyay3 Abstract The complex processes of urbanization along with the rapid expansion of urban population have changed the traits of natural hazards and cities have now become ‘crucibles of risk’. Sometimes, even the location of cities place them at greater risk from climate hazards such as cyclones, flooding, etc. These events underscore the vulnerability to natural hazards faced by the urban people, in general, and the poor, in particular, especially those living in sub-standard housing in the most vulnerable locations. Among the recent incidents of such kind, the incessant and torrential rains in the afternoon of July 26, 2005, not only caused deluge in Mumbai, but wrought equal havoc on the weak and the powerful. Why did Mumbai, the commercial capital of India, could not avert such an environmental disaster? In this paper, an attempt has been made to examine the role of various factors, which either in isolation or in conjugation with other factors might have made the circumstances more vulnerable for this urban deluge. Coupled with this, the paper discusses the need for a planning document which is prepared in the context of demographic dynamics and its significance to city planners and managers. Introduction Cities, being centres of population concentration and growth, serve as engines of economic development and innovation for the global economy and also places of refuge at times of crises such as drought or flood in the countryside. The foundations of prosperity and prominence for most cities lie in their long-standing commercial relationships with the rest of the world (Sherbinin et al 2007).