EXECUTIVE SUMMARY the Situation of Adolescents in Jharkhand Findings from the DASRA State-Wide Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dumka,Pin- 814101 7033293522 2 ASANBANI At+Po-Asa

Branch Br.Name Code Address Contact No. 1 Dumka Marwarichowk ,Po- dumka,Dist - Dumka,Pin- 814101 7033293522 2 ASANBANI At+Po-Asanbani,Dist-Dumka, Pin-816123 VIA 7033293514 3 MAHESHPUR At+Po-Maheshpur Raj, Dist-Pakur,Pin-816106 7070896401 4 JAMA At+Po-Jama,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814162 7033293527 5 SHIKARIPARA At+Po-Shikaripara,Dist-Dumka,Pin 816118 7033293540 6 HARIPUR At+Po-Haripur,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814118 7033293526 7 PAKURIA At+Po-Pakuria,Dist-Pakur,Pin816117 7070896402 8 RAMGARH At+Po-Ramgarh,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814102 7033293536 9 HIRANPUR At+Po-Hiranpur,Dist-Pakur,Pin-816104 7070896403 10 KOTALPOKHAR PO-KOTALPOKHR, VIA- SBJ,DIST-SBJ,PIN- 816105 7070896382 11 RAJABHITA At+Po-Hansdiha] Dist-Godda] Pin-814101 7033293556 12 SAROUNI At+Po-Sarouni] Dist-Godda] Pin-814156 7033293557 13 HANSDIHA At+Po-Hansdiha,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814101 7033293525 14 GHORMARA At+Po-Ghormara, Dist-Deoghar, Pin - 814120 7033293834 15 UDHWA At+Po-udhwa,Dist-Sahibganj pin-816108 7070896383 16 KHAGA At-Khaga,Po-sarsa,via-palajorihat,Pin-814146 7033293837 17 GANDHIGRAM At+Po-Gandhigram] Dist-Godda] Pin-814133 7033293558 18 PATHROLE At+po-pathrol,dist-deoghar,pin-815353 7033293830 19 FATHEPUR At+po-fatehpur,dist-Jamtara,pin-814166 7033293491 20 BALBADDA At+Po-Balbadda]Dist-Godda] Pin-813206 7033293559 21 BHAGAIYAMARI PO-SAKRIGALIGHAT,VIA-SBJ,PIN-816115 7070896384 22 MAHADEOGANJ PO-MAHADEVGANJ,VIA-SBJ,816109 7070896385 23 BANJHIBAZAR PO-SBJ AT JIRWABARI,816109 7070896386 24 DALAHI At-Dalahi,Po-Kendghata,Dist-Dumka,Pin-814101 7033293519 25 PANCHKATHIA PO-PANCHKATIA,VIA BERHATE,816102 -

Statistical Report After Every General

Cabinet (Election) Department Near Gayatri Mandi, H.E.C., Sector-2 Dhurwa, Ranchi-834004 From the desk of Chief Electoral Officer It is customary to bring out a Statistical Report after every General Election setting out the data on the candidates and the votes polled by them besides information on electorate size and polling stations etc. The present Report presents the statistics pertaining to the General Election to Jharkhand Assembly Constituency 2014. It is hoped that the statistical data contained in this booklet will be useful to all those connected with, or having an interest in, electoral administration, and politics and for researchers. (P.K. Jajoria) Chief Electoral Officer CONTENTS Sl. No. Item Page No. 1 Schedule of General Election to Jharkhand Legislative Assembly 2014 2 Re-poll Details 3 District Election Officers 4 Assembly Constituency wise Returning Officers 5 Assembly Constituency wise Assistant Returning Officers 6 Highlights 7 List of Political Parties That Contested The General Election 2014 To Jharkhand Legislative Assembly 8 Number, Name and Type of Constituencies, No. of Candidates per Constituency, List of Winners with Party Affiliation 9 Nomination Filed, Rejected, Withdrawn And Candidates Contested 10 Number of Cases of Forfeiture of Deposits 11 Performance of Political Parties And Independents 12 Performance of Women Candidates 13 Assembly Constituency Wise Electors 14 Assembly Constituency wise details of Photo Electors, EPIC holders and percentages. 15 Assembly Constituency Wise Electors And Poll Percentage -

Statistical Reports 2005

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTION, 2005 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF JHARKHAND ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI ECI-GE2005-VS Election Commission of India, 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without prior and express permission in writing from Election Commision of India. First published 2005 Published by Election Commision of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi - 110 001. Computer Data Processing and Laser Printing of Reports by Statistics & Information System Division, Election Commision of India. Election Commission of India – State Elections, 2005 to the Legislative Assembly of JHARKHAND STATISTICAL REPORT CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. 1. List of Participating Political Parties and Abbreviations 1 -2 2. Other Abbreviations in the Report 3 3. Highlights 4 4. List of Successful Candidates 5 - 7 5. Performance of Political Parties 8 -10 6. Candidates Data Summary – Summary on Nominations, 11 Rejections, Withdrawals and Forfeitures 7. Electors Data Summary – Summary on Electors, voters 12 Votes Polled and Polling Stations 8. Woman Candidates 13 - 16 9. Constituency Data Summary 17 - 97 10. Detailed Result 98 - 226 Election Commission of India-State Elections, 2005 to the Legislative Assembly of Jharkhand LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NAM PARTY HINDI NAME NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party भारतीय जनता पाट 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party बहजनु समाज पाट 3 . CPI Communist Party of India कयुिनःट पाट ऑफ इंडया 4 . CPM Communist Party of India भारत क कयुिनःट पाट (मासवाद) (Marxist) 5 . -

Annual Report 2013-14 1 MISSION OFFICE NEEDS, CIRCULAR ROAD, DEOGHAR, Area JHARKHAND-814112 PHONE: +916432-235277 of Intervention FAX: +916432-230775

ANNUAL REPORT 2013-2014 NEEDS Annual Report 2013-14 1 MISSION OFFICE NEEDS, CIRCULAR ROAD, DEOGHAR, Area JHARKHAND-814112 PHONE: +916432-235277 of Intervention FAX: +916432-230775 TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL SAHIBGANJ A RURAL TECHNOLOGY PARK (RTP), MADHUADIH, GODD BLOCK-SARWAN, PAKUR KODERMA DISTRICT- DEOGHAR, JHARKHAND GIRIDIH DEOGHAR DUMKA PALAMU CHATRA GARHWA DISTRICT OFFICE, SAHEBGANJ HAZARIBAG JAMTARA NEEDS, LATEHAR DHANBAD BOKARO C/O- ASHOK THAKUR, RAMGARH LOHARDAGA JHARKHAND SAKROGADH, OLD S.P. KOTHI, SAHEBGANJ, RANCHI JHARKHAND-816109 GUMLA KHUNTI DISTRICT OFFICE, PAKUR SARAIKELA KHARSAWAN NEEDS, SIMDEGA EAST SINGHBHUM MISSION SCHOOL ROAD, WEST SINGHBHUM NEAR QUARRY ASSOCIATION, SNDHIPADA, PAKUR, JHARKHAND-816107 DISTRICT OFFICE, JAMTARA NEEDS, C/O, MR. DIPAKGHOSH, KUMIRDAHA, NEAR SARSWATISISHUMANDIR, NALA, Pashchim JAMTARA. Champaran JHARKHAND-815355 Purba Champaran Sitamarh DISTRICT OFFICE, GODDA Gopalganj Sheohar Mudhubani Kishanganj NEEDS, Siwan Supaul Araria Muzzaffarpur Darbhanga Saran C/O, MR. DIPAK KR. BHAGAT Madhepura Saharsa Vaishali Purnia GODDA-MAHAGAMA ROAD Samastipur Bhojpur Buxar BIHAR Khagaria MOHANPUR, MAHAGAMA, Patna Begusarai Katihar GODDA, JHARKHAND Nalanda Lakhisarai Bhagalpur Kaimur Jehanabad DISTRICT OFFICE, KHUNTI (Bhabua) Rohtas Sheikhpura Jamui Aurangabad Nawada Banka NEEDS, Gaya GIRGATOLI, VIMLANIWAS KHUNTI, JHARKHAND PIN-835210 2 NEEDS Annual Report 2013-14 The Content From The Board Room- 4 About NEEDS –What We Are 5 Making Credibility a Reality - 6 Reproductive Health - 7 Child Protection - 27 Livelihood – 34 Volunteering - 47 Transparency Profile - 50 Organogram- 59 NEEDS Annual Report 2013-14 3 From The Board Room From the Desk of Secretary: term endeavors of 5 years is one of our most valued I am pleased to present the 15th annual report of partnership as the same gives us ample opportunity NEEDS of the period 2013-14. -

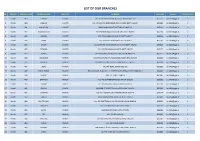

List of Our Branches

LIST OF OUR BRANCHES SR REGION BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME DISTRICT ADDRESS PIN CODE E-MAIL CONTACT NO 1 Ranchi 419 DORMA KHUNTI VILL+PO-DORMA,VIA-KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI-835 227 835227 [email protected] 0 2 Ranchi 420 JAMHAR KHUNTI VILL-JAMHAR,PO-GOBINDPUR RD,VIA-KARRA DISTT-KHUNTI. 835209 [email protected] 0 3 Ranchi 421 KHUNTI (R) KHUNTI MAIN ROAD,KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI-835 210 835210 [email protected] 0 4 Ranchi 422 MARANGHADA KHUNTI VILL+PO-MARANGHADA,VIA-KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI 835210 [email protected] 0 5 Ranchi 423 MURHU KHUNTI VILL+PO-MURHU,VIA-KHUNTI, DISTT-KHUNTI 835216 [email protected] 0 6 Ranchi 424 SAIKO KHUNTI VILL+PO-SAIKO,VIA-KHUNTI,DISTT-KHUNTI 835210 [email protected] 0 7 Ranchi 425 SINDRI KHUNTI VILL-SINDRI,PO-KOCHASINDRI,VIA-TAMAR,DISTT-KHUNTI 835225 [email protected] 0 8 Ranchi 426 TAPKARA KHUNTI VILL+PO-TAPKARA,VIA-KHUNTI, DISTT-KHUNTI 835227 [email protected] 0 9 Ranchi 427 TORPA KHUNTI VILL+PO-TORPA,VIA-KHUNTI, DISTT-KHUNTI-835 227 835227 [email protected] 0 10 Ranchi 444 BALALONG RANCHI VILL+PO-DAHUTOLI PO-BALALONG,VIA-DHURWA RANCHI 834004 [email protected] 0 11 Ranchi 445 BARIATU RANCHI HOUSING COLONY, BARIATU, RANCHI P.O. - R.M.C.H., 834009 [email protected] 0 12 Ranchi 446 BERO RANCHI VILL+PO-BERO, RANCHI-825 202 825202 [email protected] 0 13 Ranchi 447 BIRSA CHOWK RANCHI HAWAI NAGAR, ROAD NO. - 1, KHUNTI ROAD, BIRSA CHOWK, RANCHI - 3 834003 [email protected] 0 14 Ranchi 448 BOREYA RANCHI BOREYA, KANKE, RANCHI 834006 [email protected] 0 15 Ranchi 449 BRAMBEY RANCHI VILL+PO-BRAMBEY(MANDER),RANCHI-835205 835205 [email protected] 0 16 Ranchi 450 BUNDU -

GOVERNMENT of JHARKHAND E-Procurement Notice

GOVERNMENT OF JHARKHAND JHARKHAND EDUCATION PROJECT COUNCIL,RANCHI NATIONAL COMPETITIVE BIDDING(OPEN TENDER) (CIVIL WORKS) e-Procurement Notice Tender Ref No: JEPC/03/418/2016/482 Dated: 23.03.2016 1 Approximate Amount of Earnest Cost of Period of S.No Name of Work Value of Work Money/Bid Security Document Completion (Rs in lakhs) (Rs in Lakhs) (Rs) Construction of 2 Jharkhand Balika Awasiye Vidyalaya in 1 Domchanch and Chandwara Block of Koderma District of North 873.41 17.47 10,000.00 15 months Chotanagpur Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 2 Jharkhand Balika Awasiye Vidyalaya in Dulmi 2 and Chitarpur Block of Ramgarh District of North Chotanagpur 873.41 17.47 10,000.00 15 months Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 2 Jharkhand Balika Awasiye Vidyalaya in 3 Mayurhand and Kanhachatti Block of Chatra District of North 873.41 17.47 10,000.00 15 months Chotanagpur Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 1 Jharkhand Balika Awasiye Vidyalaya in 4 Chandrapura Block of Bokaro District of North Chotanagpur 436.71 8.73 10,000.00 15 months Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 2 Jharkhand Balika Awasiye Vidyalaya in 5 Baghmara and Purbi Tundi Block of Dhanbad District of North 873.41 17.47 10,000.00 15 months Chotanagpur Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 1 Jharkhand Balika Awasiye Vidyalaya in 6 Dhanbad Block of Dhanbad District of North Chotanagpur 436.71 8.73 10,000.00 15 months Division of Jharkhand. Construction of 1 Jharkhand Balika Awasiye Vidyalaya in Saria 7 Block of Giridih District of North Chotanagpur Division of 436.71 8.73 10,000.00 15 months Jharkhand. -

Officename Chanda B.O Mirzachowki S.O Boarijore B.O Bahdurchak B.O

pincode officename districtname statename 813208 Chanda B.O Sahibganj JHARKHAND 813208 Mirzachowki S.O Sahibganj JHARKHAND 813208 Boarijore B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Bahdurchak B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Beniadih B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Bhagmara B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Bhagya B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Chapri B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Mandro B.O Sahibganj JHARKHAND 813208 Maniarkajral B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Mordiha B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Rangachak B.O Godda JHARKHAND 813208 Sripurbazar B.O Sahibganj JHARKHAND 813208 Thakurgangti B.O Godda JHARKHAND 814101 Bandarjori S.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814101 S.P.College S.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814101 Dumka H.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814101 Dumka Court S.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Amarapahari B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Bhaturia B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Danro B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Sinduria B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Ramgarah S.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Gamharia B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Bandarjora B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Bariranbahiyar B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Bhalsumar B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Chhoti Ranbahiyar B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Ghaghri B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Kakni Pathria B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Khudimerkho B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Kairasol B.O Godda JHARKHAND 814102 Lakhanpur B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Mahubana B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Piprakarudih B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814102 Sushni B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Kathikund S.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Saldaha B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Sarsabad B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Kalajhar B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 T. Daldali B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Astajora B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Pusaldih B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 Amgachi B.O Dumka JHARKHAND 814103 B. -

Schools for Class-VIII in All Districts of Jharkhand State School CODE UDISE NAME of SCHOOL

Schools for Class-VIII in All Districts of Jharkhand State School CODE UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL District: RANCHI 80100510 20140117617 A G CHURCH HIGH SCHOOL RANCHI 80100376 20140105605 A G CHURCH MIDDLE SCHOOL KANKE HUSIR 80100383 20140106203 A G CHURCH SCHOOL FURHURA TOLI 80100806 20140903803 A G CHURCH SCHOOL 80100917 20140207821 A P E G RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL RATU 80100808 20140904002 A Q ANSARI URDU MIDDLE SCHOOL IRBA 80100523 20140119912 A S PUBLIC SCHOOL 80100524 20140120009 A S T V S ZILA SCHOOL 80100411 20140109003 A V K S H S 80100299 20140306614 AADARSH GRAMIN PUBLIC SCHOOL TANGAR 80100824 20140906303 ADARSH BHARTI PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOL MANDRO 80100578 20142401811 ADARSH H S MCCLUSKIEGANJ 80100570 20142400503 ADARSH HIGH SCHOOL SANTI NAGAR KHALARI 80100682 20142203709 ADARSH HIGH SCHOOL KOLAMBI TUSMU 80100956 20141108209 ADARSH UCHCHA VIDYALAYA MURI 80100504 20140116916 ADARSHA VIDYA MANDIR 80100846 20140913601 ADARSHHIGH SCHOOL PANCHA 80100214 20140603012 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA JINJO THAKUR GAON 80100911 20140207814 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA RATU 80100894 20140202702 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA TIGRA GURU RATU 80100119 20140704204 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA TUTLO NARKOPI 80100647 20140404507 ADIWASI VIKAS HIGH SCHOOL BAJRA 80101106 20140113028 AFAQUE ACADEMY 80100352 20140100813 AHMAD ALI MORDEN HIGH SCHOOL 80100558 20140123620 AL-HERA PUBLIC SCHOOL 80100685 20142203716 AL-KAMAL PLAY HIGH SCHOOL 80100332 20142303514 ALKAUSAR GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL ITKI RANCHI 80100741 20140803807 AMAR JYOTI MIDDLE CUM HIGH SCHOOL HARDAG 80100651 20140404516 -

Activities of DLSA for the Month April 2019

Office Of The District Legal Services Authority, Deoghar Phone No.06432-275496 Email; - [email protected] DLSA/DEO/Letter No. 818 Dated: - 06.05.2019 From: - Secretary, District Legal Services Authority, Deoghar. To, The Deputy Secretary, Jharkhand State Legal Services Authority, Ranchi. Ref.: - Letter No. JHALSA/928 dated 21.03.2016. Sir, In compliance of above letter No., I am sending herewith the required information regarding details of programmes and other activities of the District Legal Services Authority, Deoghar for the month of April, 2019 including the programme relating to Legal-aid to poor and number of beneficiaries of different categories and alternative dispute Resolution Mechanisms- ADR Centers, Permanent Lok Adalats / Lok Adalats. No. of cases disposed off, no. of Lok Adalat held etc. during the Month of April, 2019 Activities of DLSA, Deoghar for the month of April, 2019 Legal-aid Beneficiaries Sl. No Month No. of Persons benefited 1 April, 2019 12( in which 11 Penal Advocate & 1 Certified Copy) Legal Awareness Camp Sl. No Month No. of Legal No. of Persons benefited in Awareness Camp Awareness Camp 1 April, 2019 24 431 Lok Adalats (Monthly/ National/ Mega) Sl. Month Name of Lok Adalat Date Cases disposed Amount Settled No (including (In Rs.) pre-litigation) 1 April, 2 2019 Monthly Lok Adalat 27.04.2019 63 2,01,575/- Jail Adalats Sl. Date No. Case disposed off No. of Jail imprisoner released No 1 14.04.2019 Nil Nil Activities in DLSA April' 2019 1. 01.04.2019- Training Programme for Penal Lawyers under Training Module-III. 2. -

DEOGHAR SUBDIVISION BLOCK : DEOGHAR Father/Husband Shop Licence S No

DEOGHAR SUBDIVISION BLOCK : DEOGHAR Father/Husband Shop Licence S No. Dealer Name. Address. Dealer Code. Mobile. Name. Name. No. 1 AJIT KUMAR SANATAN PDS VILL JETHOTAND PO 34220010051 16-2006 9934139168 CHOUDHARY KHORIPANAN PS JASIDIH 2 AMIN PRASAD YADAV CHARITAR YADAV PDS VILL KHORIPANAN 34220010044 34-91 8521653438 3 BABITA DEVI RAJKISHOR PDS VILL BANKA PO 34220010034 19-07 9771347317 PRASAD BANKA PS JASIDIH 4 BAJRANGI SHG BHAGIYA DEVI PDS BASWARIA 34220010018 74-09-10 7250784353 BANDE 5 BALESHWAR HARI PD PDS JHHILIUACHANDIH 34220010066 232-85 9572788494 CHOUDHARI CHOUDHARI 6 BALMIKI TURI KALAR TURI PDS TABAGHAT 34220010009 14-96 9973591592 7 BALRAM SHARMA LATE NAKUL PDS PATARDIH JASIDIH 34220010071 31-91 9431783256 SHARMA 8 BARKI DEVI KISUN MURMU PDS CHARKHIPAHARI 34220010043 6-99 9430105497 9 BASANT SHG MEDHANI DEVI PDS JHILLIUACHANDIH 34220010056 43-09-10 9955334210 10 BEDNATH SHG PRAKASH YADAV PDS MATHURAPUR 34220010020 133-09 9199954937 11 BHAWATI SHG RAYMI DEVI PDS CHANDIH BASMATA 34220010085 141-09- 8877197481 10 12 BIJLI SHG SIMRA PINKI DEVI PDS KHASPEKA 34220010027 210-09 9430160270 DEOGHAR 13 BISHNU KISHKU KARU KISHKU PDS PICHHARIBAD 34220010017 58-91 8969550485 14 BISHNUDEV DAS LATE BIJAY DAS PDS SARASANI 34220010001 24-2011 9234492645 MANIKPUR 15 BISHWANATH YADAV LATE BALBHADRA PDS BAGHMARA 34220010073 215-85 9234762645 PRASAD YADAV 16 BIVIHUTI BHUSHAN LATE RAJ PDS GAURIPUR 34220010028 203-85 9334103035 SINGH NARAYAN SINGH 17 CHAND SWAYAM LATIFAN BIBI PDS VILL GANGTI 34220010004 52-09 9263937248 SAHAYATA SAMITI GANGTI 18 -

Under MGNREGA in Deoghar District Sl Appl Name of Father's/ Permanent Address Address for Correspondence Date of Sex Cat Disability Qualification Remarks No

District Rural Development Agency, Deoghar Details of all applications for the post of Technical Assistant (A.E) under MGNREGA in Deoghar district Sl Appl Name of Father's/ Permanent Address Address for Correspondence Date of Sex Cat Disability Qualification Remarks No. No. Applicant Husband's Name Birth % E/D/P Essential Additional Village/Mohalla/ P.O/Thana Block District B.E / B.Tech (Civil) M.Tech (Civil) [MCA] Locality M.Sc (Comp) / PGDCA E.Qual % of Total E.Qual % of Total E.Qual % of Total Marks Marks Marks Obtained Obtained Obtained 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 1 1 Rohit Kumar Nageshwar Tharidulampur Deosangh Deoghar Deoghar Same As PMT Add 31.01.94 M Gen B.Tech 60.00 NA Das (Civil) 2 2 Ajay Kumar Baldeo Das Jant Karon Karon Deoghar Vill-Bherwa Nawadih, 06.09.95 M SC B.E(Civil) 70.40 NA Bharti Post-Madhupur, Dist- Deoghar- 815353 3 3 Manjeet Arjun Prasad Govindpur Haripurkolva Madhupur Deoghar Same As PMT Add 02.05.96 M SC B.Tech 70.00 NA Kumar Das Das 815353 (Civil) 4 4 Pranay Kumar Sitaram Das Tarabad Rikhiya Mohanpur Deoghar Vill-Gandhi Nagar 07.10.96 M SC B.Tech 70.10 NA DE (Civil) 814113 Gali no 04 Po- (Civil) Deoghar District Deoghar-814112 5 5 Animesh Sanjay Kumar Rangamatiya Pathardda Sarath Deoghar Viil-Thadi Dulampur 20.12.97 M SC B.Tech 62.40 NA Kumar 814149 Po- Devsang District- (Civil) Deoghar-814114 6 6 Gautam Raj Kumar Orpa Kenmankathi Deoghar Deoghar Same As PMT Add 10.04.91 M SC B.Tech 65.40 NA Kumar Das Das 814142 (Civil) 7 7 Gulam Abdul Md Taiyab Baksidih Chetadih Giridih Giridih Same -

10To19: Dasra Adolescents Collaborative - in Partnership with National Health Mission, Jharkhand

10to19: Dasra Adolescents Collaborative - In partnership with National Health Mission, Jharkhand Learnings and progress from implementation over 2018-2021 In collaboration with our Implementing Partner: Quest Alliance Objective of this document The 10to19: Dasra Adolescent Collaborative (10to19) has been working in the state of Jharkhand to improve education outcomes for adolescents. Quest Alliance, the implementation partner, has been supporting these efforts, particularly in 5 blocks in Deoghar district – Deoghar, Devipur, Madhupur, Palojori and Sonaraithari. This document summarizes the key learnings from their collaborative action, and provides recommendations for the state’s education department for scaling some of the learnings and progress. This document is a reflection of learnings from Dasra and its implementing partners as a part of the 10to19 Collaborative, based on the experience of implementing on ground in Jharkhand. It is key to note that the learnings shared here have not been statistically validated or backed by extensive research – but are rather early outcomes and good practices that have emerged from the programme implementation, self-evaluated by the 10to19 partners themselves. Introduction to 10to19’s work in Jharkhand Over the last 3 years, 10to19’s implementation adolescent issues related to health, education, partner Quest Alliance (QA) has been working safety and empowerment with in-school and out-of-school adolescents in the district of Deoghar, in Jharkhand. The Establishment of a Community of Practice of objective of programs implemented by QA is to 200+ NGOs and experts aligned on adolescent enhance and prolong the learning journey of issues adolescents, by ensuring that all adolescents feel motivated to complete their secondary Roll out of an adolescent-led initiative ‘Ab education.