Oil, Gas & Energy Law Intelligence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System

The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System Chi Kong Chyong, Pierre Noël and David M. Reiner September 2010 CWPE 1051 & EPRG 1026 The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System EPRG Working Paper 1026 Cambridge Working Paper in Economics 1051 Chi Kong Chyong, Pierre Noёl and David M. Reiner Abstract We calculate the total cost of building Nord Stream and compare its levelised unit transportation cost with the existing options to transport Russian gas to western Europe. We find that the unit cost of shipping through Nord Stream is clearly lower than using the Ukrainian route and is only slightly above shipping through the Yamal-Europe pipeline. Using a large-scale gas simulation model we find a positive economic value for Nord Stream under various scenarios of demand for Russian gas in Europe. We disaggregate the value of Nord Stream into project economics (cost advantage), strategic value (impact on Ukraine’s transit fee) and security of supply value (insurance against disruption of the Ukrainian transit corridor). The economic fundamentals account for the bulk of Nord Stream’s positive value in all our scenarios. Keywords Nord Stream, Russia, Europe, Ukraine, Natural gas, Pipeline, Gazprom JEL Classification L95, H43, C63 Contact [email protected] Publication September 2010 EPRG WORKING PAPER Financial Support ESRC TSEC 3 www.eprg.group.cam.ac.uk The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System1 Chi Kong Chyong* Electricity Policy Research Group (EPRG), Judge Business School, University of Cambridge (PhD Candidate) Pierre Noёl EPRG, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge David M. Reiner EPRG, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge 1. -

Transporting Russian Natural Gas to Western Europe – from Source to Market

FACT SHEET December 2013 Transporting Russian Natural Gas to Western Europe – From Source to Market Overview of the pipelines connecting to Nord Stream Owner of the pipeline Operator 1 Bovanenkovo-Ukhta pipeline 2 SRTO-Torzhok pipeline 3 Brotherhood pipeline Gazprom Gazprom 4 Pochinki-Gryazovets pipeline 5 Gryazovets-Vyborg pipeline 6 Nord Stream Pipeline Nord Stream AG shareholders: Nord Stream AG OAO Gazprom (51%), Wintershall Holding GmbH (15.5%), E.ON SE (15.5%), N.V. Nederlandse Gasunie (9%), GDF SUEZ (9%) OPAL Gastransport W & G Beteiligungs-GmbH & Co. KG (80%), GmbH & Co. KG, 7 OPAL pipeline Lubmin-Brandov Gastransport GmbH (20%) Lubmin-Brandov Gastransport GmbH NEL Gastransport GmbH, NEL Gastransport GmbH (51%), Gasunie Gasunie Ostseeanbindungsleitung GmbH 8 NEL pipeline Ostseeanbindun (25%), gsleitung GmbH, Fluxys Deutschland GmbH (24%) Fluxys Deutschland GmbH 1 Industriestrasse 18 Moscow Branch 6304 Zug, Switzerland ul. Znamenka 7, bld. 3 Tel. +41 (0) 41 766 91 91 119019 Moscow, Russia Fax +41 (0) 41 766 91 92 Tel. +7 (0) 495 229 65 85 www.nord-stream.com Fax +7 (0) 495 229 65 80 Gas production sources Russia is one of the countries with the largest gas reserves in the world. With 32,900 bcm, Russia has 17.6% of the world's currently known natural gas reserves.1 This is equal to around 56 years of Russian gas production at 2012 levels or around 74 years of EU gas demand at 2012 levels. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates the ultimately recoverable gas resources2 in Russia to be three times as high – 127,000 bcm, of which 21,000 bcm have already been produced. -

The Real Financial Cost of Nord Stream 2

THE REAL FINANCIAL COST OF NORD STREAM 2 – ECONOMIC SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS OF THE ALTERNATIVES TO THE OFFSHORE PIPELINE THE REAL FINANCIAL COST OF NORD STREAM 2 – economic sensitivity analysis of the alternatives to the offshore pipeline Author: Piotr Przybyło Economy and Energy Programme Warsaw 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Pipeline from nowhere to nowhere 6 II. A €17.2 billion investment 7 III. The construction cost of offshore vs onshore 8 IV. Three times cheaper alternative onshore routes 9 V. The true motives behind the Nord Stream 2 14 PIPELINE FROM NOWHERE Siberia to Baltic coast in Russia. Similarly, newly TO NOWHERE constructed pipelines will transport 55 bcma of gas over 800 km down south from the Baltic shore In any economic analysis of Nord Stream 2 the first in Germany to one of the biggest European gas question to be considered is the actual cost of the hubs in Austria, its final destination. Consequently, project. Over the last couple of years, a variety of the overall construction cost of Nord Stream 2 publications have provided widely differing cost route should include all the additional necessary projections. The recent data suggest that Nord infrastructure to achieve this objective. Conclusively, Stream 2 capital investment will reach €9,5-10 the construction cost of the offshore pipeline is billion. only a portion of the bigger project which aims to deliver Russian gas to South-West of Europe. Yet, the €9,5-10 billion is not the final construction cost of the project. Nord Stream 2 will not fulfil its Here, the main focus will be put on the economic function in isolation. -

Nord Stream Delivers Gas to Lubmin

European gas grid gas European gas from Nord Stream is delivered to the the to delivered is Stream Nord from gas At the landfall facility in Lubmin, Germany, Germany, Lubmin, in facility landfall the At LUBMIN HEATH: European Mainland European High Tech AN ENERGY SITE A Connecting Nord the at Arrives Natural Gas Gas Natural for Quality In the context of the energy Hub on the strategy 2020 of Mecklenburg- Stream and Safety Western Pomerania, Lubmin developed into an energy hub German Coast with a range of energy sources Delivers More than 167 million standard cubic metres feeding electricity into the German (later: cubic metres) of natural gas can be distribution grid. The Lubmin landfall The Bovanenkovo oil and gas gas transport systems. Currently, condensate deposit is the main up to 36 billion cubic metres of processed in the receiving station in Lubmin facility is the logistical natural gas base for the Nord gas can flow through the OPAL every day. A sophisticated series of valves, filters, link between the Nord Gas to Lubmin DISMANTLING AND Stream Pipeline. Discovered and pipeline annually. This amount preheating, measuring and control facilities Stream Pipeline and CONSTRUCTION estimated gas reserves amount is enough to supply a third of ensure that the gas is of top quality, and the right the European gas to 4.9 trillion cubic meters which Germany with natural gas for a quantities are flowing to the connecting pipelines distribution grid. The makes the Bovanenkovo field a year. The pipeline runs south at the right pressure and temperature. In 1995, the Nord nuclear power natural gas that arrives reliable source of natural gas for from Lubmin to Brandov, in the plant in Lubmin was shut down. -

PDF of the Fact Sheet

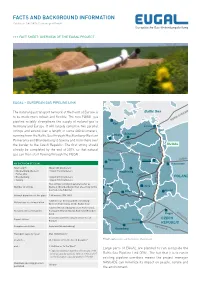

FACTS AND BACKGROUND INFORMATION Publisher: GASCADE Gastransport GmbH ••• FACT SHEET: OVERVIEW OF THE EUGAL PROJECT EUGAL – EUROPEAN GAS PIPELINE LINK The natural gas transport network at the heart of Europe is Baltic Sea to be made more robust and flexible: The new EUGAL gas pipeline reliably strengthens the supply of natural gas to NORD STREAM Kiel Germany and Europe. It will largely comprise two parallel Greifswald strings and extend over a length of some 480 kilometers, running from the Baltic Sea through Mecklenburg-Western Hamburg Schwerin Pomerania and Brandenburg to Saxony and from there over NEL the border to the Czech Republic. The first string should EUGAL OPAL already be completed by the end of 2019, so that natural NETRA gas can then start flowing through the EUGAL. FGL306 Hannover BERLIN JAMAL AN OVERVIEW OF EUGAL Frankfurt/Oder Total length About 480 kilometers Hameln Mecklenburg-Western About 102 kilometers Magdeburg Pomerania Brandenburg About 272 kilometers JAGAL POLAND Saxony About 106 kilometers OPAL Two strings running in parallel as far as Kassel Number of strings Weißack (Brandenburg), then one string to the Leipzig German-Czech border Erfurt Dresden Internal diameters of the pipes 1.40 meters (DN 1400) Lubmin near Greifswald (Mecklenburg- Natural gas receiving station Western Pomerania, on the Baltic Sea) Lubmin (Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania), Network connection points Kienbaum (Brandenburg), Radeland (Branden- NET4GAS burg) Prague MEGAL Deutschneudorf (Saxony, German-Czech GAZELLE Export station CZECH Border) Waidhaus REPUBLIC Compressor station Radeland (Brandenburg) NET4GAS Nuremberg Transport capacity / year Max. 55 billion m³ of which … 45.1 billion m³ to the Czech Republic* EUGAL application route (schematic illustration) and … 9.9 billion m³ to the West* Large parts of EUGAL are planned to run alongside the * Capacity expansion based on the results of the binding capacity auctions held on 6 March 2017 Baltic Sea Pipeline Link OPAL. -

Ad Hoc Arbitration Under the Rules of Arbitration of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law and Pursuant to the Energy Charter Treaty

AD HOC ARBITRATION UNDER THE RULES OF ARBITRATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW AND PURSUANT TO THE ENERGY CHARTER TREATY NORD STREAM 2 AG (Claimant) VS EUROPEAN UNION (Respondent) EUROPEAN UNION COUNTER-MEMORIAL ON THE MERITS Legal Service European Commission Rue de la Loi/Wetstraat 200 1049 Bruxelles/Brussel Christophe BONDY External Counsel Steptoe & Johnson LLP 3 May 2021 Ad Hoc Arbitration between Nord Stream 2 AG European Union and the European Union Counter-Memorial on the Merits ____________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1. THE CLAIMANT HAS FAILED TO PROVE ITS FACTUAL ALLEGATIONS ................................................................................ 4 1.1.1. The Amending Directive pursues legitimate and achievable public policy objectives ............................. 4 1.1.2. The Amending Directive did not involve a “dramatic and radical regulatory change” ........................... 5 1.1.3. The Amending Directive will not have the alleged on NSP2AG’s investment ..... 6 1.1.4. The NS2 pipeline project was not “deliberately excluded” from the Derogation Regime ....................... 7 1.1.5. The Claimant has failed to prove that the Amending Directive underwent an improper legislative process ................................................................................................................................................... -

The OPAL Exemption Decision: Past, Present, and Future

January 2017 The OPAL Exemption Decision: past, present, and future OIES PAPER: NG 117 Katja Yafimava The contents of this paper are the author’s sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies or any of its members. Copyright © 2017 Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (Registered Charity, No. 286084) This publication may be reproduced in part for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. ISBN 978-1-78467-077-1 ii January 2017: The OPAL Exemption Decision: past, present, and future Preface To the casual gas reader, the dispute over the use of OPAL pipeline capacity is an issue for regulatory experts. But nearly eight years after the first regulatory decision and more than five years after the pipeline started operating it seems extraordinary that the share of capacity that Gazprom can use (if not required by other parties) remains unresolved. Indeed as we entered 2017, the controversy became even greater with the Commission being sued by a member state for having attempted to resolve this long-running problem causing the case to be referred to the European Court of Justice (CJEU). How and why we arrived at this point are the questions Katja Yafimava’s paper is designed to answer. Few of us, if we have only followed the headlines of the OPAL story, will have appreciated the complexity of the (competition and energy) regulatory issues, and in particular the impact of the evolving capacity allocation framework and development of capacity auction platforms, on the different options for resolving the dispute. -

Open Season: WINGAS TRANSPORT Extends Capacity Reservation in the OPAL Gas Pipeline

WINGAS TRANSPORT GmbH & Co. KG Press Release October 8, 2007 Stefan Leunig PI•07•08 ( +49 561 301•3301 4 +49 561 301•1321 press@wingas•transport.de Open Season: WINGAS TRANSPORT extends capacity reservation in the OPAL gas pipeline · Capacity in the German connection to the Nord Stream Baltic Sea pipeline · Initial use starting with 2010 Kassel. WINGAS TRANSPORT GmbH & Co KG has started another process for ordering transport capacities in a new gas pipeline. From Monday, October 8, 2007, 8 a.m. (CEST) interested parties can submit offers to use the OPAL (Ostsee•Pipeline•Anbindungs•Leitung, Baltic Sea Connection Pipeline) within the scope of a so•called open season procedure. This pipeline is currently being planned in the course of implementing the connection line to the Nord Stream Baltic Sea pipeline. Specifically, this means that capacities may be requested to inject natural gas into OPAL, especially in Greifswald and Olbernhau, and to withdraw gas from OPAL or – in this connection – from other points in WINGAS TRANSPORT’s existing pipeline network. More details about the conditions for taking part in this procedure can be found on the network operator's web site (www.wingas•transport.de). “From the start of the procedure all the interested parties have six weeks to acknowledge the terms and conditions of business, register to participate in the new Open Season, and formulate their capacity requirements,” explains Ingo Neubert, Managing Director of WINGAS TRANSPORT. Subsequently, a technical and economic concept will be drafted. In the second phase specific capacities and conditions will be defined. It is planned that the main key points will be concluded before the end of 2007. -

Gas Transport Begins from the Lubmin Landfall Facility in Germany the Landfall Facility Is the Logistical Link Between Nord Stream and the European Gas Grid

NEwSletter about ThE NaturalFacts gaS pIpEline THROUGH ThE baltic sea issue 20 / NovEmbEr 2011 The two lines of the Nord Stream pipeline system reach land at lubmin. at the landfall station, the natural gas is purified, measured, and if necessary adjusted to the proper temperature prior to transport. Gas transport Begins from the Lubmin Landfall Facility in Germany The landfall facility is the logistical link between Nord Stream and the European gas grid he landfall facility in lines also comes from the region into a gas transportation agree- Along its 470-kilometre route, the Lubmin is a hub of sorts, where the Yuzhno-Russkoye ment with OOO Gazprom Export pipeline runs through three Ger- t the actual switching gas field is located. It is the big- to book up to 55 bcm capacity man federal states, and crosses point of a cross-border project gest natural gas field developed annually. The pipelines will trans- a total of 172 roads, four high- that will contribute to a secure in Russia to date. Nord Stream port gas from the entry point in ways, 27 rail lines, and 39 bod- supply of energy to Europe for shareholders Gazprom, E.ON Russia to the exit point in Germa- ies of water. Since the gas loses decades. At the same time, the and Wintershall have a stake in ny, where the gas will be received pressure over the long route, it landfall facility is only a small part this gas field, where reserves by the connecting OPAL (Baltic is repressurised at a compres- of the puzzle in the entire frame- are estimated at 600 billion Sea Pipeline Link) and NEL (North sor station in Baruth, south of work of the onward transport of cubic metres (bcm). -

The OPAL Pipeline: Controversies About the Rules for Its Use and the Question of Supply Security

Centre for Eastern Studies NUMBER 229 | 17.01.2017 www.osw.waw.pl The OPAL pipeline: controversies about the rules for its use and the question of supply security Agata Loskot-Strachota with assistance from Szymon Kardaś, Rafał Bajczuk The record volumes of gas supplied via the OPAL and Nord Stream pipeline in recent weeks have been accompanied by controversy over the rules for utilisation of the OPAL pipeline’s capacity. There has long been uncertainty as to the actual content of the decision taken by the European Commission at the end of October 2016, the full text of which was published on 9 January 2017. Both the clash of interests between companies and states about how to use the gas pipeline, and the different interpretations of the impact of Gazprom’s increased utilisation of OPAL due to the new EC regulations on the situation on the gas markets in the EU, including in Central Europe and Poland, have been revealed. Uncertainty concerning the principles of the pipeline’s use has also been increased by Poland’s formal challenge of the EC’s decision. The decisions by the European Court of Justice and a court in Düsseldorf related to this mat- ter, which temporarily suspend the implementation of the EC’s regulations, have not yet been published. This deepens the doubts about the principles for increased utilisation of the OPAL pipeline, and about the legality of the increase in gas flows along the route which has been apparent since 22 December. At the same time, these gas flows are affecting the situation on the European (and especially Central European) gas markets. -

Nord Stream Pipeline Connected to OPAL

PRESS RELEASE Nord Stream Pipeline Connected to OPAL Last welding seam joining first Nord Stream line and European pipeline network complete Pipeline system ready for next steps of commissioning Lubmin, August 25, 2011. The direct link between the major Russian reserves in Siberia and the European natural gas market is in place: The first line of the Nord Stream Pipeline is now connected to the OPAL natural gas pipeline (Ostsee-Pipeline-Anbindungs-Leitung – Baltic Sea Pipeline Link). “The pipeline system is now ready for the next complex steps of bringing the pipeline on stream, which means we will be able to commission the first of the Nord Stream twin pipelines in the fourth quarter of 2011 as planned,” Dr. Georg Nowack, Nord Stream AG project manager for Germany, explained. “The connecting pipeline OPAL, which will pick up the natural gas from Nord Stream and transport it onwards, is already complete,” said Bernd Vogel, Managing Director of OPAL NEL TRANSPORT GmbH, a company of the WINGAS Group which will operate the connecting pipeline. “So we are ready. The Russian natural gas can come.” The last welding seam connecting the first line of the Nord Stream Pipeline and the OPAL pipeline was completed on the grounds of the natural gas transfer station in Lubmin near Greifswald, where the Nord Stream Pipeline reaches the German coast. Over 200 staff from regional and national companies are currently working on the 12-hectare piece of land near the Lubmin port preparing the transfer station for subsequent operations. Together the participating companies are investing around 100 million euros in Lubmin alone. -

Nord Stream 2 – a Political and Economic Contextualisation

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Kai-Olaf Lang and Kirsten Westphal Nord Stream 2 – A Political and Economic Contextualisation RP 3 March 2017 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2017 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They reflect the views of the author(s). SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 21/2016) The translation of this paper was funded by the German Foreign Office. Table of Contents 5 Issues and Recommendations 7 Nord Stream 2 – A Commercial Project with Political Dimensions 9 Nord Stream 2 as a Business Project 9 The commercial logic of Nord Stream 2 AG from the Western business perspective 9 Gazprom’s calculation 12 Nord Stream 2 and Regulation in the EU’s Internal Market 12 The legal framework in the internal market 12 Nord Stream 2 – Legal approaches and contested issues 17 The connecting pipelines for Nord Stream 2 19 Market Trends, Market (Power) Relations and Security of Supply 19 Nord Stream 2 and the gas supply in north- western Europe 19 Nord Stream 2: Price trends and liquidity 20 Transit through Ukraine and unresolved problems 22 The gas markets in central eastern Europe 24 Nord Stream and changing gas flows in eastern Europe 26 Nord Stream 2 – The Political Dimension 26 Nord Stream 2 and the strategic energy triangle 27 Nord Stream 2 in the context of climate and environmental considerations 28 Criticisms from central eastern and south-eastern Europe 29 Interests of individual member states 35 Summary and Outlook 38 Recommendations for Germany and the European Union 39 Abbreviations Dr.