Self-Reinforced Nylon 6 Composite for Smart Vibration Damping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Mechanical Vibrators Mass-Spring System Equation Of

Primary Mechanical Vibrators Music 206: Mechanical Vibration Tamara Smyth, [email protected] • With a model of a wind instrument body, a model of Department of Music, the mechanical “primary” resonator is needed for a University of California, San Diego (UCSD) complete instrument. November 15, 2019 • Many sounds are produced by coupling the mechanical vibrations of a source to the resonance of an acoustic tube: – In vocal systems, air pressure from the lungs controls the oscillation of a membrane (vocal fold), creating a variable constriction through which air flows. – Similarly, blowing into the mouthpiece of a clarinet will cause the reed to vibrate, narrowing and widening the airflow aperture to the bore. 1 Music 206: Mechanical Vibration 2 Mass-spring System Equation of Motion • Before modeling this mechanical vibrating system, • The force on an object having mass m and let’s review some acoustics, and mechanical vibration. acceleration a may be determined using Newton’s second law of motion • The simplest oscillator is the mass-spring system: – a horizontal spring fixed at one end with a mass F = ma. connected to the other. • There is an elastic force restoring the mass to its equilibrium position, given by Hooke’s law m F = −Kx, K x where K is a constant describing the stiffness of the Figure 1: An ideal mass-spring system. spring. • The motion of an object can be describe in terms of • The spring force is equal and opposite to the force its due to acceleration, yielding the equation of motion: 2 1. displacement x(t) d x m 2 = −Kx. -

Free and Forced Vibration Modes of the Human Fingertip

applied sciences Article Free and Forced Vibration Modes of the Human Fingertip Gokhan Serhat * and Katherine J. Kuchenbecker Haptic Intelligence Department, Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems, 70569 Stuttgart, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Computational analysis of free and forced vibration responses provides crucial information on the dynamic characteristics of deformable bodies. Although such numerical techniques are prevalently used in many disciplines, they have been underutilized in the quest to understand the form and function of human fingers. We addressed this opportunity by building DigiTip, a detailed three-dimensional finite element model of a representative human fingertip that is based on prior anatomical and biomechanical studies. Using the developed model, we first performed modal analyses to determine the free vibration modes with associated frequencies up to about 250 Hz, the frequency at which humans are most sensitive to vibratory stimuli on the fingertip. The modal analysis results reveal that this typical human fingertip exhibits seven characteristic vibration patterns in the considered frequency range. Subsequently, we applied distributed harmonic forces at the fingerprint centroid in three principal directions to predict forced vibration responses through frequency-response analyses; these simulations demonstrate that certain vibration modes are excited significantly more efficiently than the others under the investigated conditions. The results illuminate the dynamic behavior of the human fingertip in haptic interactions involving oscillating stimuli, such as textures and vibratory alerts, and they show how the modal information can predict the forced vibration responses of the soft tissue. Citation: Serhat, G.; Kuchenbecker, Keywords: human fingertips; soft-tissue dynamics; natural vibration modes; frequency-response K.J. -

VIBRATIONAL SPECTROSCOPY • the Vibrational Energy V(R) Can Be Calculated Using the (Classical) Model of the Harmonic Oscillator

VIBRATIONAL SPECTROSCOPY • The vibrational energy V(r) can be calculated using the (classical) model of the harmonic oscillator: • Using this potential energy function in the Schrödinger equation, the vibrational frequency can be calculated: The vibrational frequency is increasing with: • increasing force constant f = increasing bond strength • decreasing atomic mass • Example: f cc > f c=c > f c-c Vibrational spectra (I): Harmonic oscillator model • Infrared radiation in the range from 10,000 – 100 cm –1 is absorbed and converted by an organic molecule into energy of molecular vibration –> this absorption is quantized: A simple harmonic oscillator is a mechanical system consisting of a point mass connected to a massless spring. The mass is under action of a restoring force proportional to the displacement of particle from its equilibrium position and the force constant f (also k in followings) of the spring. MOLECULES I: Vibrational We model the vibrational motion as a harmonic oscillator, two masses attached by a spring. nu and vee! Solving the Schrödinger equation for the 1 v h(v 2 ) harmonic oscillator you find the following quantized energy levels: v 0,1,2,... The energy levels The level are non-degenerate, that is gv=1 for all values of v. The energy levels are equally spaced by hn. The energy of the lowest state is NOT zero. This is called the zero-point energy. 1 R h Re 0 2 Vibrational spectra (III): Rotation-vibration transitions The vibrational spectra appear as bands rather than lines. When vibrational spectra of gaseous diatomic molecules are observed under high-resolution conditions, each band can be found to contain a large number of closely spaced components— band spectra. -

Control Strategy Development of Driveline Vibration Reduction for Power-Split Hybrid Vehicles

applied sciences Article Control Strategy Development of Driveline Vibration Reduction for Power-Split Hybrid Vehicles Hsiu-Ying Hwang 1, Tian-Syung Lan 2,* and Jia-Shiun Chen 1 1 Department of Vehicle Engineering, National Taipei University of Technology, Taipei 10608, Taiwan; [email protected] (H.-Y.H.); [email protected] (J.-S.C.) 2 College of Mechatronic Engineering, Guangdong University of Petrochemical Technology, Maoming 525000, Guangdong, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 January 2020; Accepted: 25 February 2020; Published: 2 March 2020 Abstract: In order to achieve better performance of fuel consumption in hybrid vehicles, the internal combustion engine is controlled to operate under a better efficient zone and often turned off and on during driving. However, while starting or shifting the driving mode, the instantaneous large torque from the engine or electric motor may occur, which can easily lead to a high vibration of the elastomer on the driveline. This results in decreased comfort. A two-mode power-split hybrid system model with elastomers was established with MATLAB/Simulink. Vibration reduction control strategies, Pause Cancelation strategy (PC), and PID control were developed in this research. When the system detected a large instantaneous torque output on the internal combustion engine or driveline, the electric motor provided corresponding torque to adjust the torque transmitted to the shaft mitigating the vibration. To the research results, in the two-mode power-split hybrid system, PC was able to mitigate the vibration of the engine damper by about 60%. However, the mitigation effect of PID and PC-PID was better than PC, and the vibration was able to converge faster when the instantaneous large torque input was made. -

The Physics of Sound 1

The Physics of Sound 1 The Physics of Sound Sound lies at the very center of speech communication. A sound wave is both the end product of the speech production mechanism and the primary source of raw material used by the listener to recover the speaker's message. Because of the central role played by sound in speech communication, it is important to have a good understanding of how sound is produced, modified, and measured. The purpose of this chapter will be to review some basic principles underlying the physics of sound, with a particular focus on two ideas that play an especially important role in both speech and hearing: the concept of the spectrum and acoustic filtering. The speech production mechanism is a kind of assembly line that operates by generating some relatively simple sounds consisting of various combinations of buzzes, hisses, and pops, and then filtering those sounds by making a number of fine adjustments to the tongue, lips, jaw, soft palate, and other articulators. We will also see that a crucial step at the receiving end occurs when the ear breaks this complex sound into its individual frequency components in much the same way that a prism breaks white light into components of different optical frequencies. Before getting into these ideas it is first necessary to cover the basic principles of vibration and sound propagation. Sound and Vibration A sound wave is an air pressure disturbance that results from vibration. The vibration can come from a tuning fork, a guitar string, the column of air in an organ pipe, the head (or rim) of a snare drum, steam escaping from a radiator, the reed on a clarinet, the diaphragm of a loudspeaker, the vocal cords, or virtually anything that vibrates in a frequency range that is audible to a listener (roughly 20 to 20,000 cycles per second for humans). -

Ch 11 Vibrations and Waves Simple Harmonic Motion Simple Harmonic Motion

Ch 11 Vibrations and Waves Simple Harmonic Motion Simple Harmonic Motion A vibration (oscillation) back & forth taking the same amount of time for each cycle is periodic. Each vibration has an equilibrium position from which it is somehow disturbed by a given energy source. The disturbance produces a displacement from equilibrium. This is followed by a restoring force. Vibrations transfer energy. Recall Hooke’s Law The restoring force of a spring is proportional to the displacement, x. F = -kx. K is the proportionality constant and we choose the equilibrium position of x = 0. The minus sign reminds us the restoring force is always opposite the displacement, x. F is not constant but varies with position. Acceleration of the mass is not constant therefore. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eeYRkW8V7Vg&feature=pl ayer_embedded Key Terms Displacement- distance from equilibrium Amplitude- maximum displacement Cycle- one complete to and fro motion Period (T)- Time for one complete cycle (s) Frequency (f)- number of cycles per second (Hz) * period and frequency are inversely related: T = 1/f f = 1/T Energy in SHOs (Simple Harmonic Oscillators) In stretching or compressing a spring, work is required and potential energy is stored. Elastic PE is given by: PE = ½ kx2 Total mechanical energy E of the mass-spring system = sum of KE + PE E = ½ mv2 + ½ kx2 Here v is velocity of the mass at x position from equilibrium. E remains constant w/o friction. Energy Transformations As a mass oscillates on a spring, the energy changes from PE to KE while the total E remains constant. -

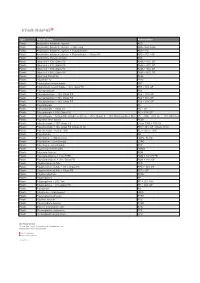

Table 1. SOME NAMES and ABBREVIATIONS of Plastics and Elastomers

TABlE 1. SOME NAMES AND ABBREVIATIONS OF PlASTICS AND ElASTOMERS. Common name Abbreviation Acetal (homopolymer and copolymer) POM-H and POM-K Acrylate styrene acrylonitrile ASAorAAS Acrylate modified styrene acrylonitrile ASAorAAS Acrylic acid ester rubber ACM Acrylonitrile butadiene rubber or nitrile butadiene rubber NBR Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene ABS Acrylonitrile styrene/chlorinated polyethylene ACS Acrylonitrile methyl methacrylate AMMA Acrylonitrile styrene/EPR rubber or, acrylonitrile ethylene propylene styrene AES Alpha methyl styrene AMS Atactic polypropylene APPorPP-A Butadiene rubber or, cis-1,4-polybutadiene rubber or, polybutadiene rubber BR Butadiene styrene block copolymer BDS Butyl rubber IIR Bulk molding compound BMC Casein formaldehyde CF Cellulose acetate CA Cellulose acetate butyrate CAB Cellulose acetate propionate CAP Cellulose nitrate CN Chlorinated polyethylene CPEorCM Chlorinated polyvinyl chloride CPVC or, PVC-C Chloro-polyethylene or, chlorinated polyethylene. CM or CPE or, PE-C Chloroprene rubber or, polychloroprene rubber CR Chlorotrifluoroethylene ethylene copolymers ECfFE Cis-polyisoprene or, cis-1,4-polyisoprene IR Coumarone indene resins CIR Diallyl phthalate DAP Diallyl isophthalate DAIP Dough molding compound DMC Elastomeric alloy melt processable rubber EA-MPR Elastomeric alloy thermoplastic vulcanizate EA-TPV Epichlohydrin rubber CHR Epoxy or, epoxide EP Epoxy or, epoxide, with glass fiber EPGF Ethyl cellulose EC Ethylene acryic acid EAA Ethylene propylene diene monomer (an EPR terpolymer) EPDM -

Synthetic Polymeric Materials for Bone Replacement

Review Synthetic Polymeric Materials for Bone Replacement Mônica Rufino Senra and Maria de Fátima Vieira Marques * Technology Center, Bloco J, Instituto de Macromoleculas Professora Eloisa Mano, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, IMA-UFRJ, Av. Horacio Macedo, 2030, Rio de Janeiro RJ 21941-598, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 November 2020; Accepted: 18 December 2020; Published: 19 December 2020 Abstract: Some treatment options available to repair bone defects are the use of autogenous and allogeneic bone grafts. The drawback of the first one is the donor site’s limitation and the need for a second operation on the same patient. In the allograft method, the problems are associated with transmitted diseases and high susceptibility to rejection. As an alternative to biological grafts, polymers can be used in bone repair. Some polymers used in the orthopedic field are poly(methyl methacrylate), poly(ether-ether-ketone), and ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE). UHMWPE has drawn much attention since it combines low friction coefficient and high wear and impact resistance. However, UHMWPE is a bioinert material, which means that it does not interact with the bone tissue. UHMWPE composites and nanocomposites with hydroxyapatite (HA) are widely studied in the literature to mitigate these issues. HA is the main component of the inorganic phase in the natural bone, and the addition of this bioactive filler to the polymeric matrix aims to mimic bone composition. This brief review discusses some polymers used in orthopedic applications, focusing on the UHMWPE/HA composites as a potential bone substitute. Keywords: poly(methyl methacrylate); poly(ether-ether-ketone); ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene; hydroxyapatite; orthopedic applications 1. -

Leonhard Euler - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 14

Leonhard Euler - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 14 Leonhard Euler From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Leonhard Euler ( German pronunciation: [l]; English Leonhard Euler approximation, "Oiler" [1] 15 April 1707 – 18 September 1783) was a pioneering Swiss mathematician and physicist. He made important discoveries in fields as diverse as infinitesimal calculus and graph theory. He also introduced much of the modern mathematical terminology and notation, particularly for mathematical analysis, such as the notion of a mathematical function.[2] He is also renowned for his work in mechanics, fluid dynamics, optics, and astronomy. Euler spent most of his adult life in St. Petersburg, Russia, and in Berlin, Prussia. He is considered to be the preeminent mathematician of the 18th century, and one of the greatest of all time. He is also one of the most prolific mathematicians ever; his collected works fill 60–80 quarto volumes. [3] A statement attributed to Pierre-Simon Laplace expresses Euler's influence on mathematics: "Read Euler, read Euler, he is our teacher in all things," which has also been translated as "Read Portrait by Emanuel Handmann 1756(?) Euler, read Euler, he is the master of us all." [4] Born 15 April 1707 Euler was featured on the sixth series of the Swiss 10- Basel, Switzerland franc banknote and on numerous Swiss, German, and Died Russian postage stamps. The asteroid 2002 Euler was 18 September 1783 (aged 76) named in his honor. He is also commemorated by the [OS: 7 September 1783] Lutheran Church on their Calendar of Saints on 24 St. Petersburg, Russia May – he was a devout Christian (and believer in Residence Prussia, Russia biblical inerrancy) who wrote apologetics and argued Switzerland [5] forcefully against the prominent atheists of his time. -

Mechanical Properties Thermoplastic Laminates of Polycarbonate

Scienc ile e & Singh et al., J Textile Sci Eng 2018, 8:4 xt e E T n : g DOI 10.4172/2165-8064.1000366 f i o n l e a e n r r i n u g o Journal of Textile Science & Engineering J ISSN: 2165-8064 Research Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Mechanical Properties Thermoplastic Laminates of Polycarbonate- Polyetherimide Blend with Glass Fibers Singh JC1*, Srivastava M2, Singh RK2 and Yadaw SB3 1Indian Institute of Technology, New Delhi, India 2Central Institute of Plastics Engineering and Technology, Hajipur, India 3Defence Material & Stores Research & Development Establishment, Kanpur, India Abstract Thermoplastic Laminates of Polycarbonate (PC)/Polyetherimide (PEI) blend with glass fibers were prepared by solution blending of PC & PEI in different ratio of 100/0, 95/5, 90/10, 85/15 and 80/20 using Dichloromethane as solvent followed by applying the resulting blend solutions over the cut sheet size (30 × 25 cm) of woven mat glass fibers & dried overnight, then stacked up 12 flies of the impregnates and consolidated in a hot press at 300ºC and 3-4 ton (30 kg/cm2) pressure for a duration of one hour & cooled. The laminates of PC/PEI blends/woven mat glass fibers were studied for their mechanical properties viz: Tensile, Flexural, Impact and Inter Laminar Shear Strength and thermo-mechanical properties viz: TGA, DSC, DMA as well as examination of morphology by SEM. The mechanical properties of laminates of PC/PEI blends/woven mat glass fibers shows an increasing trend in Inter Laminar Shear Strength, Tensile and Flexural Strength upto 20% PEI while Impact Strength shows an increase upto 10% and decreases while the percentage of PEI increases. -

Type Material Name Abbreviation Plastic Acrylonitrile Butadiene

Type Material Name Abbreviation Plastic Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene ABS Plastic Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene - High-Temp ABS - high temp Plastic Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene + Polycarbonate ABS + PC Plastic Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene + Polycarbonate + Glass Fill ABS + PC + GF Plastic Acrylonitrile styrene acrylate ASA Plastic Nylon 6-6 + 10% Glass Fill PA66 + 10% GF Plastic Nylon 6-6 + 20% Glass Fill PA66 + 20% GF Plastic Nylon 6-6 + 30% Glass Fill PA66 + 30% GF Plastic Nylon 6-6 + 50% Glass Fill PA66 + 50% GF Plastic Nylon 6-6 Polyamide PA66 Plastic Polyamide 12 PA12 Plastic Polybutylene terephthalate PBT Plastic Polybutylene terephthalate + 30% Glass Fill PBT+ 30% GF Plastic Polycaprolactam PA6 Plastic Polycaprolactam + 20% Glass Fill PA6 + 20% GF Plastic Polycaprolactam + 30% Glass Fill PA6 + 30% GF Plastic Polycaprolactam + 50% Glass Fill PA6 + 50% GF Plastic Polycarbonate PC Plastic Polycarbonate + Glass Fill PC + GF Plastic Polycarbonate + 10% Glass Fill PC + 10% GF Plastic Polycarbonate + Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene + 20% Glass Fill + 10% Stainless Steel fiber PC + ABS + 20% GF + 10% SS Fiber Plastic Polyether ether ketone PEEK Plastic Polyetherimide + 30% Glass Fill Ultem 1000 + 30% GF Plastic Polyetherimide + 40% Glass Fill (Ultem 2410) PEI + 40% GF (Ultem 2410) Plastic Polyetherimide + Ultem 1000 PEI + Ultem 1000 Plastic Polyethylene PE Plastic Polyethylene - High-Density HDPE, PEHD Plastic Polyethylene - Low-Density LDPE Plastic Polyethylene terephthalate PET Plastic Polymethyl methacrylate PMMA Plastic Polyoxymethylene -

HOOKE's LAW and Sihlple HARMONIC MOTION by DR

Hooke’s Law by Dr. James E. Parks Department of Physics and Astronomy 401 Nielsen Physics Building The University of Tennessee Knoxville, Tennessee 37996-1200 Copyright June, 2000 by James Edgar Parks* *All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Objective The objectives of this experiment are: (1) to study simple harmonic motion, (2) to learn the requirements for simple harmonic motion, (3) to learn Hooke's Law, (4) to verify Hooke's Law for a simple spring, (5) to measure the force constant of a spiral spring, (6) to learn the definitions of period and frequency and the relationships between them, (7) to learn the definition of amplitude, (8) to learn the relationship between the period, mass, and force constant of a vibrating mass on a spring undergoing simple harmonic motion, (9) to determine the period of a vibrating spring with different masses, and (10) to compare the measured periods of vibration with those calculated from theory. Theory The motion of a body that oscillates back and forth is defined as simple harmonic motion if there exists a restoring force F that is opposite and directly proportional to the distance x that the body is displaced from its equilibrium position. This relationship between the restoring force F and the displacement x may be written as F=-kx (1) where k is a constant of proportionality. The minus sign indicates that the force is oppositely directed to the displacement and is always towards the equilibrium position.